CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The United States Supreme Court heard arguments Wednesday in an emotionally charged free speech case prompted when members of Westboro Baptist Church protested the funeral of a Marine killed while serving in Iraq.

On March 3, 2006, Fred Phelps, who founded Westboro in Topeka, Kan., stood with six of his parishioners outside the entrance of St. John's Catholic Church in Westminster, Md., with signs reading "God Hates the USA," "Fag Troops," "Thank God for IEDs," "God Hates Fags," and "God Hates You," among others.

They were protesting the funeral of 20-year-old Marine Matthew Snyder because, they contend, the United States is awash in sin for harboring gays and lesbians.

"God is cursing America," Margie Phelps, daughter of Westboro founder Fred Phelps, told reporters following the hearing. "It is a curse for your young men and women to be coming home in body bags. And if you want that to stop, stop sinning."

Margie Phelps, known for the inflammatory rhetoric and invective that are trademarks of any Westboro protest, adopted a deferential tone before the nine justices. She argued that staging a protest 1,000 feet from the church while complying with the police regulations and state laws falls well within members' First Amendment right to free speech.

But Albert Snyder, Matthew's father, sued for damages of emotional distress and was awarded $5 million by a district court, a ruling that was then overturned by the fourth circuit court of appeals, the decision Snyder and his lawyers then appealed to the Supreme Court.

"I want to know how you would feel if someone stood 30 feet away from the main vehicle entrance of a church when you were trying to bury your mother with a sign that says, 'Thank God for Dead Sluts,'" the anguished father told National Public Radio prior to the case. "Is 'fag' worse than 'slut?' You tell me that somebody has the right to do that."

The justices' decision will likely turn on the two key questions: whether, as a matter of law, a line can be drawn that separates protected free speech on a public matter from private harassment; and whether Matthew Snyder and his father could be considered public figures rather than private citizens based on the fact that Matthew's funeral was publicized in the local paper.

Balancing privacy and First Amendment rights was of obvious concern to the justices, said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Irvine, School of Law and a constitutional scholar. "It seems that there was great sympathy with the privacy claim, but also a real struggle to accommodate allowing liability with freedom of speech," he said.

Following the hearing, the plaintiff's attorney, Sean Summers, flat out rejected the notion that either Snyder could be called a public figure.

"I hope that this isn't just a case about speech -- it's about harassment, targeted harassment at a private person's funeral," he said.

Summers added that Westboro members had focused on the funeral, as they do with other funerals, as a way to get publicity.

"The reality is, if they would have had this same protest at a court in Kansas, none of us would be here," he told reporters. "There's a reason they came to that funeral that day, and it was to hijack someone else's private event because none of us would listen to them unless they came somewhere where they could command an audience."

But Phelps countered that opinion.

"Look, you all know that people put obituaries in the newspaper with the date, time, and location of funerals because they want the public to come and bow down to that dead body," she said following the case. "Now, you don't get to do that -- as they say, have your cake it eat it too -- without people answering when you go into the public airwaves."

During the hearing, Phelps argued that Snyder was publicly posing the question of how to stop the war and "a little church ... where servants of God are found" was merely answering his question.

"You step into the public discussion and make public statements and then someone answers you," she told the justices. "It wasn't an issue of seeking maximum publicity, it was an issue of using a public platform."

And that was the point on which Chief Justice John Roberts paid particular attention -- whether Westboro had chosen to protest the funeral in search of "maximum publicity" or because it bore particular relevance to the public debate about the war.

"I wonder if that matters," Roberts asked Phelps, the question on which he was most engaged from the bench.

One by one, several justices also signaled their doubts that the Snyders qualified as public figures.

The was a case about "a private family's grief," said Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg. Why should the First Amendment "tolerate" that type of protest?

Before posing a hypothetical, Justice Elena Kagan offered, "Let's say we disagree with you that Mr. Snyder had injected himself in the public debate."

Finally, Justice Anthony Kennedy told Phelps that her position assumed that you can simply "follow a citizen around" and asked her to "help us" find some line even in the absence of a law.

Phelps responded, "We don't do 'follow around' in this church. We were out of sight, out of sound."

But Phelps repeatedly declined to answer the hypotheticals posed by the justices.

The justices, however, also tasked the plaintiffs' attorney with suggesting how the First Amendment treats public debates differently than private citizens.

"So speech on a public matter that is directed to a private citizen should be treated differently under the law?" Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Summers, before challenging him to find a Supreme Court case that handled public versus private speech differently.

Summers cited Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., a case in which a private attorney was awarded damages after a magazine article falsely identified him as a communist.

But Sotomayor and Ginsberg both objected that the case was about defamation and therefore distinctly different.

Justice Stephen Breyer suggested that the court needed "a rule" or an "approach" as to how the First Amendment can distinguish between the private party and the public effort.

The case has drawn an interesting array of amicus briefs, with 42 U.S. senators taking the side of the petitioner, Albert Snyder, while the American Civil Liberties Union and nearly every major news outlet across the country has sided with the respondent, Fred Phelps Sr.

Snyder made his own appeal outside the courtroom.

"Our son -- a hero -- dead, only to be compounded by the family being targeted and subject to personal attacks, venomous hate, and injustice at Matt's funeral," he said, wearing a button picture of his son in uniform on his left lapel. "That is something no family should have to live through."

After the hearing, Summers said he was "confident" that the justices would find in his clients' favor but added, "There's no guarantees in this business.{C}{C}"

For her part, Phelps was equally as assured, if not defiant.

"Your destruction is imminent!" she sternly warned reporters with their host of cameras and microphones pointed her direction. "Now, when it comes, don't stand there and pretend that the servants of God did not warn you and your blood is not on our hands -- that's what we've accomplished," she concluded.

Finally, Phelps innocently asked, "Is that all, guys?" before turning to NPR's Nina Totenberg and enthusing at what a pleasure it was to meet her.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

Tennessee Senate passes bill making 'recruiting' for trans youth care a felony

April 14 2024 11:17 AM

Italy’s prime minister says surrogacy ‘inhuman’ as party backs steeper penalties

April 14 2024 10:36 AM

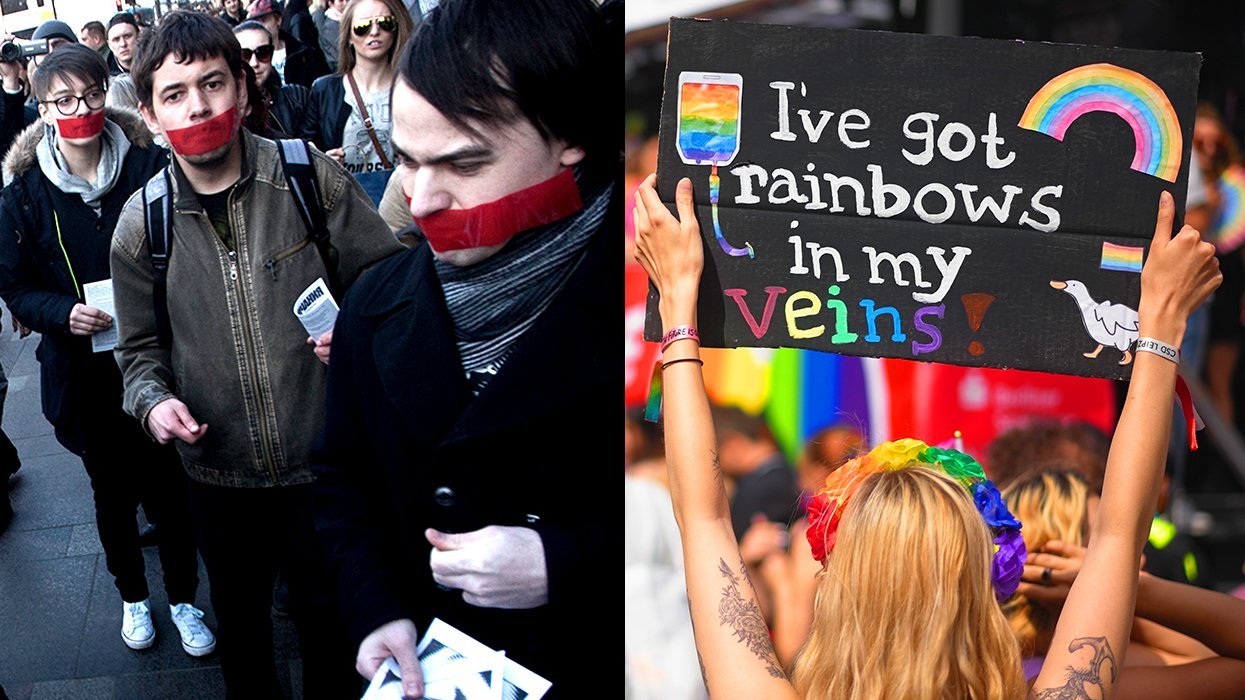

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

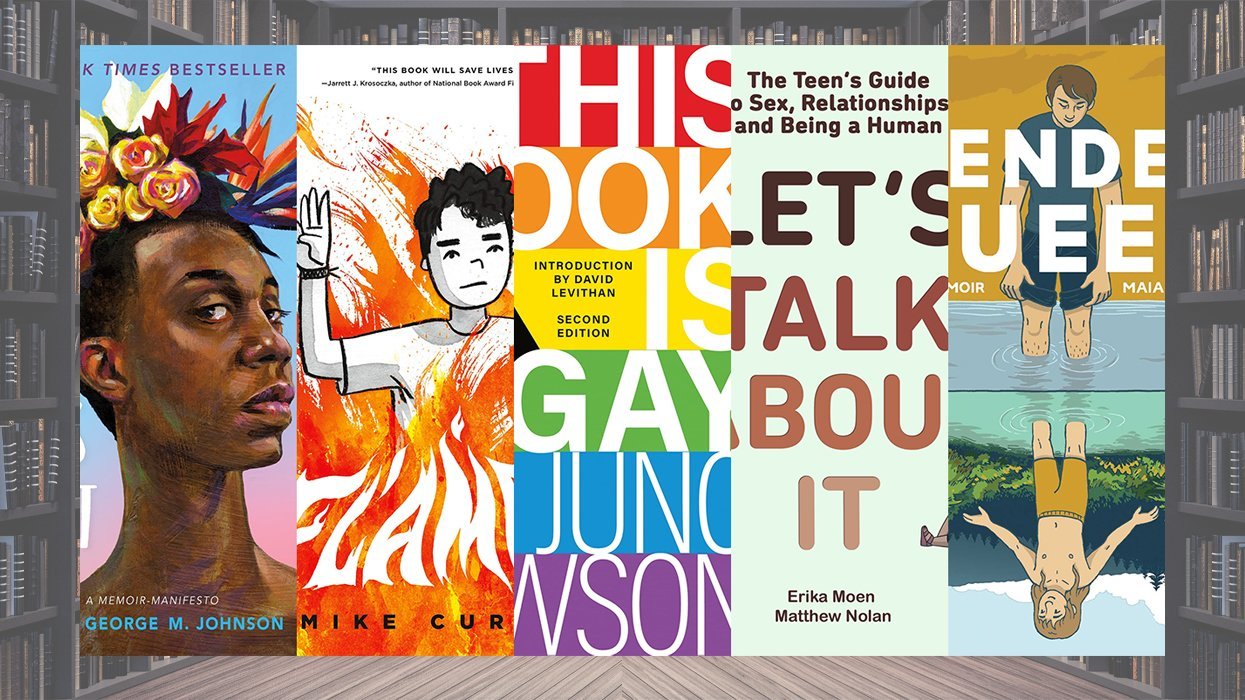

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM

Investigation launched after man screams homophobic slurs at queer couples on D.C. metro

April 13 2024 9:59 AM

Germany makes it easier to change gender and name on legal documents

April 12 2024 6:06 PM

A youth's call to action on this Day of NO Silence

April 12 2024 5:00 PM

Democrats introduce resolution in support of LGBTQ+ youth

April 12 2024 4:35 PM

Colton Underwood is hoping to create a gay reality TV dating show

April 12 2024 4:28 PM

Idaho closes legislative session with a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ laws

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedElevating pet care with TrueBlue’s all-natural ingredients

April 12 2024 1:39 PM