A lesbian couple went to Uganda to understand what gay life is truly like.

January 31 2014 8:00 AM EST

May 26 2023 2:14 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

A few days before our trip to Uganda, I received a comical yet stern email from my father telling me not to hold hands with my girlfriend in public. "I've got better things to do in my remaining years than go visit you in a grungy jail in Uganda," he joked, yet proceeded to tell me how serious he was.

Uganda's Parliament had just passed its antigay bill, which proposed life imprisonment for "aggravated homosexuality." Anyone with HIV or anyone considered a "serial offender" who engaged in gay sex, even if it was consensual or protected, could be sent to jail. The bill, which had not yet by signed by the president, also included prison time for those who reached out to LGBT people, and tourists weren't exempt from punishment.

I assured my father that my girlfriend was not a fan of public displays of affection (much to my dismay) and that he had nothing to worry about, as we'd be traveling as "friends."

It was a strange feeling. Parliament had passed a bill going against not only something I strongly believed in but something I embodied, something I was. Even though we'd been saving and planning for more than a year, I started to wonder if going to Uganda and abiding by "their rules" meant I was condoning the bill.

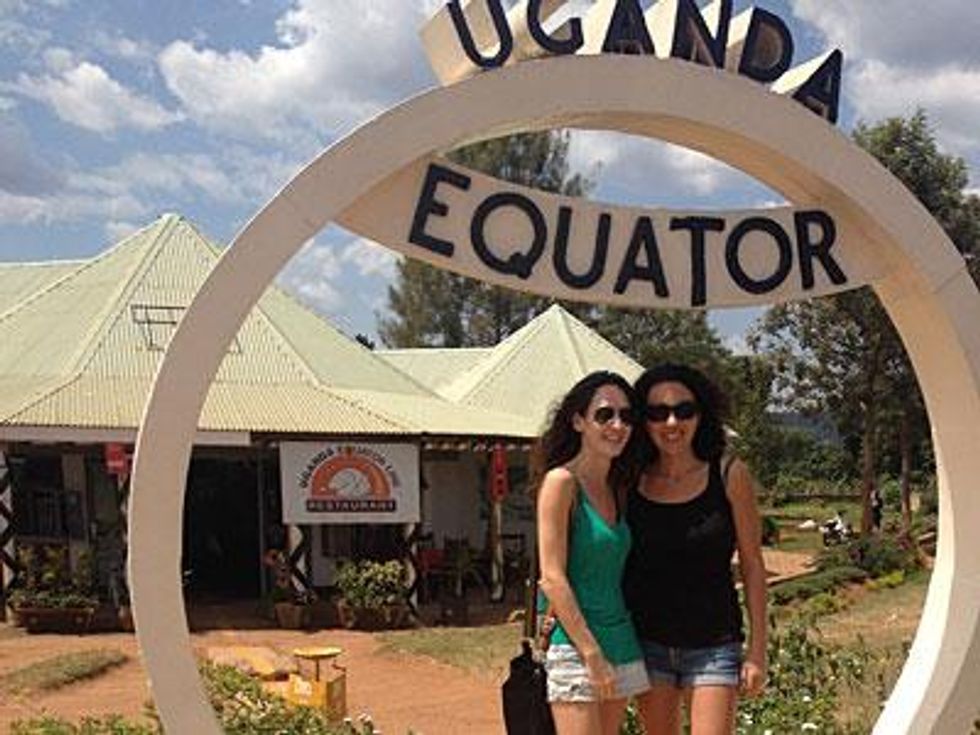

On the other hand, I told myself that by not going, I was letting this nonsensical legislation stand in my way and somehow I was letting them win. It had been my girlfriend's dream to see the mountain gorillas in their natural habitat, and East Africa always held great intrigue for me, especially Uganda. And so instead of being deterred, the two of us were motivated to do some digging and speak with as many people as possible while we were on the ground. We wanted to understand how regular Ugandans truly felt.

Having recently watched the documentary Call Me Kuchu about gays in Uganda, we started by tracking down the late David Kato's mother. Kato, Uganda's first openly gay man, led the gay rights movement in East Africa and was one of the founding members of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) as well as a prominent international figure before he was killed in 2011. His mother had a brief cameo in the movie, and in light of the bill we wanted to get her reaction.

On our second day into the trip, we hopped in a taxi and managed to find (with much help along the way) David's hometown, the tiny village of Nakawala, over an hour outside of Kampala. When we arrived at the house, Lidia and Lilian, David's mother and niece, came to greet us. It was eerily comfortable, as if they were expecting us, but as it turns out they just wanted us off the road and out of sight.

"We don't like speaking to white people anymore," David's niece Lilian explained as we sat on the couch in their two-room clay hut. "They [her fellow villagers] think that because David's mother sees white people that she supports gays, so the village has isolated her."

After the documentary, plenty of white people came to pay their respects to the family. But in Uganda, as we quickly learned, if you're friends with whites, they think you support homosexuality and are in fact bringing "it" into the country. This mentality is especially prevalent in the villages.

What I found most shocking about visiting the Katos was their antigay point of view. Perhaps I was naive to think that they'd be gay-supportive just because of who David was and the work that he did. But much to my surprise, Lidia had no idea (so she said) that her son was gay, nor did she realize how major an international figure he was until the funeral. "I'm happy he was such a good person and I support his advocacy work. I just don't support the fact that he was gay," she explained as she stared longingly at the picture of him on the wall wearing a shirt with the rainbow flag on it.

Yet, despite her antigay feelings, Lidia still opposed the bill. She said it's unfair because it implicates those who might not be gay but who just want to help. Lilian agreed but felt that life imprisonment was too harsh of a sentence and explained that two years in jail was a more "just" punishment. Our taxi driver, Deo, who we'd "forced" to stay with us for fear of being stranded in the village, chimed into the conversation saying that five months was enough time in prison. He likened being gay to drinking in that "you're the only one who can decide when to stop."

It's strange how sometimes the more you talk about something, even as obscene as jail time for homosexuality, it somehow becomes "normal" in the context of who you're with. Five months in prison sounded better than two years and two years was way better than a lifetime. Lidia, Lilian and Deo were able to bring a rationale to their beliefs, one that seemed utterly insane to me, yet in their presence was somehow acceptable. I kept wondering what they'd do if I told them my "photographer" was more than a work colleague, more than a friend.

It was hard at times, not because I ever felt threatened, but because I had to hold myself back. The majority of Ugandans wouldn't suspect that two women traveling together, sans husbands, would be lesbians. Most people thought it was sad that we weren't married and offered to wed us (in exchange for visas, of course). But this was my vacation, and I wanted to be able to hold my girlfriend's hand or kiss her on the street if I had an impulse, but I had to put up a wall, and in doing so, for a very brief moment, I must have felt how so many gay Ugandans feel every single day. It was disheartening, and at the same time I was grateful that I could easily hop on a plane, go back home, and tear down that wall.

It was a nice release, one I didn't even realize I needed, when I was able to be honest with someone about our relationship for the first time during the trip. On our last day in Kampala we met with Frank Mugisha, current director of SMUG and recipient of the 2011 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award. We met Frank and his personal assistant, Richard, in a mall about 20 minutes outside the city. They didn't want us to see SMUG's office for fear of people discovering its location. They were cautious about whom they spoke with and where they held meetings and even securing the interview took several attempts. As "out" as they seemed, it was obvious that they weren't free.

During our talk I asked Frank how he felt when he saw places like Canada and the United States and other European countries with such liberal gay rights laws.

"I'm envious of your country and others -- it seems like heaven," he said. "I look at other countries and think why can't we be like that? But I know they worked hard for their freedom and it takes work." As my girlfriend and I sat for an hour listening to Frank's stories about temporarily having to flee Uganda and move to Kenya, his mission to combat the bill no matter how challenging, and the help and security he tries to give the LGBT community, we saw that his commitment to the cause was evidently unwavering.

"For me, my sacrifice is all the way. I'd sacrifice everything including my life until I see that I'm creating a change," he said

The next day as we continued our trip toward the slightly more "liberal" Tanzania, I felt both sad and invigorated. Frank's vision of a more inclusive and accepting country and world was infectious. I just hoped these changes he was working so hard to create would come to fruition within his lifetime. It was a question both my girlfriend and I asked ourselves as we crossed the border into Tanzania, where I didn't have to worry as much about holding her hand.

SAM MEDNICK, a Toronto native, has worked and lived all over the world, including Fiji, Argentina, Ireland, Africa, Lebanon and the Philippines. She now lives in Barcelona and works as the local correspondent for the Travel Media Group at USA Today. In addition to her journalistic work, Sam has her own life and business coaching company, where she specializes in helping people with time management and motivational coaching as well as small business and transitional coaching. Before embarking on her coaching career, Sam worked in Ghana as a foreign correspondent for a Canadian nongovernmental organization (Journalists for Human Rights) and was the executive radio producer for an internationally syndicated lifestyle show based in New York City. See Sam's coaching philosophies at BlueprintCoaching.ca.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!