All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

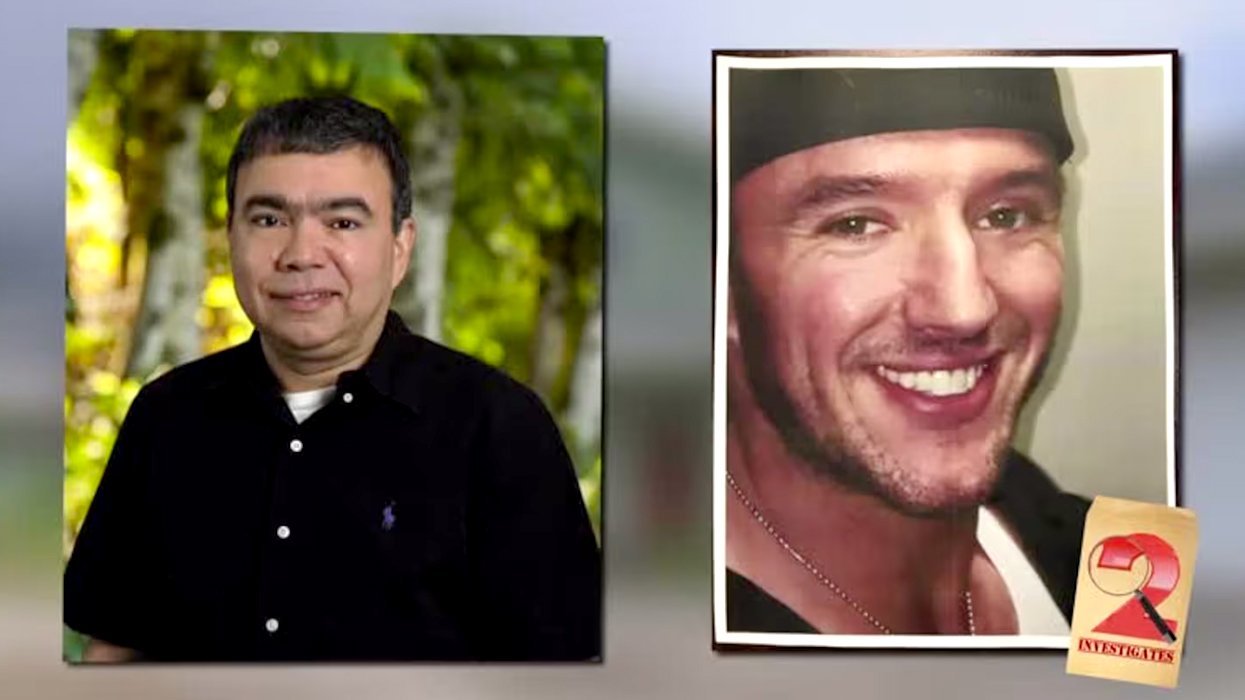

Brian Fricke wanted to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, who served as a sergeant in the Marines. So he joined the elite fighting corps in 2000.

Fricke knew, even as a teenager, that to join the armed forces meant giving up personal freedoms. What he didn't realize was how much more difficult that would be for a gay man--who would have to be closeted.

Two years later, while he was stationed in Okinawa, Japan, Fricke had had enough. A friend and fellow marine was going on about having sex with women when Fricke blurted out, "You know, I'm not attracted to women."

Fricke, now a sergeant, says he half-expected to be kicked out of the military right then and there. But his peer's reaction shocked him: "Oh, really? That's no big deal."

"No big deal?" Fricke recalls thinking at the time. "Despite the hype about 'don't ask, don't tell' and the trouble gays would cause in the ranks [if they were allowed to serve openly], it was not that big of a deal. And it wouldn't be today. I remained Corporal Fricke, and I happened to be gay."

Indeed, a recent Zogby poll shows that 73% of service members say they would be comfortable serving alongside gays and lesbians. A poll in 1993--the year the Pentagon's antigay "don't ask, don't tell" policy went into effect--reported that only 13% of enlisted personnel supported gay soldiers, demonstrating why there is now a strong push to end the ban on gays serving openly. A bill to repeal "don't ask, don't tell" is being reintroduced this year in Congress. It's gaining an impressive list of cosponsors, while the list of retired military leaders publicly coming out against the ban is growing into an all-star gallery of top brass.

In January, John M. Shalikashvili, retired chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and former secretary of Defense William Cohen both publicly urged Congress to reconsider the "don't ask, don't tell" policy [see sidebar].

The Zogby poll showed that nearly one in four service members report knowing that someone in their unit is gay or lesbian, including 21% of those in combat units. "We have known anecdotally that many gay service members are opening up to at least some of their colleagues," says Steve Ralls, communications director for the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network, a Washington, D.C.-based group advocating for gay soldiers. "And those who know a gay colleague are more open to repealing this discriminatory policy."

Aaron Belkin, director of the Michael D. Palm Center (formerly known as the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military) at the University of California, Santa Barbara, helped design the poll to test whether the statistics would bear out the anecdotal evidence. "In one sense the change is surprising because it has only been a decade and a half since the policy was instituted," says Belkin. "But there has been huge cultural change and public opinion shift in that time, and that affects the opinions of those who serve in the military."

So why hasn't the ban gone the way of segregation, especially during a time when qualified personnel are desperately needed overseas? The problem, says Vince Patton, 52, a retired U.S. Coast Guard master chief petty officer, is that people from his generation are just plain stuck. "Gen Xers are more accepting of gays and lesbians and more tolerant in general," he says. "It's more than just an issue of sexual orientation for them. It's a matter of freedom of expression. The under-40 crowd has a lot more intelligence when it comes to these issues than those from my era."

In 2003, Patton participated in "Operation Handshake" as an adviser to the USO, spending three weeks with U.S. troops in the Persian Gulf and Southwest Asia. While talking with soldiers during a tour of Afghanistan, he asked them if they had any problems serving alongside gays. No one expressed a negative opinion.

The soldiers cared only whether their fellow soldiers were willing to do the job and watch their backs, Patton recalls. Being gay, or Baptist, or Jewish, or whatever didn't matter to them. "But then I took that conversation to the commanding officers who were my age, and they all said, 'Oh, hell, no!' " he says.

Sonya Contreras, a former Army sergeant and recruiter who was discharged under "don't ask, don't tell," saw firsthand how some commanders actually use the policy against gays and lesbians. In fact, it wasn't until she proved so successful as a recruiter--and was on track to become the youngest recruiting station commander ever--that her superiors used her homosexuality against her. She even went through a diversity training workshop during which a new company commander made antigay comments.

Commanding officers set the tone, says Contreras, 31. "And when it behooves someone to discriminate against you, and they are able to do so under 'don't ask, don't tell,' they will."

Retired lieutenant general Claudia Kennedy, who served in the Army from 1968 to 2000 and is heterosexual, has commanded gay and lesbian service members since the 1970s. She also broke ground in the military, having become the first female three-star general in the U.S. Army in June 1997.

As a woman, Kennedy is keenly aware of how the military perpetuates its symbols of masculinity, and that makes it difficult for straight service members to speak out on behalf of their gay brethren. "The stigma attached is huge," says Kennedy. "And there is such pressure from Army alumni--those who have been out of the military 10 or 20 years--for the Army not to change.

"But the bigger obligation," she continues, "is to do what's right and to have the best qualified military you can."

Even if the policy changed tomorrow, however, institutional changes in the military will take longer, predicts Contreras. "When the policy changes, the cultural change will take much longer," she says. "Gay people in the military right now are not going to come out en masse, because a policy change is not going to change the way people think and feel."

In light of the Zogby poll and the take-back of Congress by the Democrats, Massachusetts congressman Marty Meehan, a Democrat, released a statement in December revealing his intention to reintroduce the Military Readiness Enhancement Act, a bill to repeal "don't ask, don't tell" that Meehan first introduced in March 2005. "I will also be asking for the first congressional hearings on gays in the military since 1993," Meehan wrote. "I know that when my colleagues see and understand the evidence against 'don't ask, don't tell,' they will be motivated to join me in the fight for repeal."

Fricke, who is now 25 and plans to write a book about his experience, agrees. "If the nation knew what this policy is really doing and how lives are being ruined, it would open their eyes," he says.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

Supreme Court lets Idaho enforce law criminalizing gender-affirming care for minors