CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

"It was a euphoria," says Emory Etheridge of his first experience with crystal methamphetamine. "It was amazing." Real Worlder Chris Beckman remembers thinking simply, This is really great! New Yorker Mike, while high on crystal, experienced "the most productive day at work that I've ever had," while San Franciscan Alejandro Diesta felt like "I could do anything."

As I sit here among my stacks of letters awaiting response, videotapes awaiting screening, and books awaiting reading, with the little computer bell ringing to alert me to another e-mail awaiting an answer, I can see the appeal of a drug like crystal. It's more than mother's little helper: It's hours of pure joy, energy, and self-confidence in chemical form. If I were burdened not just with work responsibilities but also with the loneliness and self-doubt of a lifetime of being told I was evil for being gay, how much more appealing would that magic powder seem?

Problem is--as the brave men in our cover story learned--the cost of temporary euphoria may be permanent. Etheridge has resigned himself to never again having sex as good as the sex he remembers on crystal. Diesta's energy boost was followed by "paranoia, hopelessness, and...incomprehensible demoralization." Portland, Ore., resident John Motter ended up with a prison record.

No wonder a Tennessee ex-addict says in Beckman's book, Clean, "Methamphetamine is a drug of the devil."

Saying no to selling your soul to crystal--or, even more bravely, wresting your soul back from its clutches--is about more than just a person's workload, relationship dramas, or childhood traumas. Partly it's that "nature versus nurture" debate in a new form: Are some people biologically or psychologically predisposed to addiction? Or, as one friend in recovery suggested to me, is meth the one drug that can turn anyone into an addict?

While the mainstream media seem obsessed with meth's destructiveness, with law enforcement, and with legislative intervention, we at The Advocate think they're missing the big story. The solution to the meth epidemic is not in harsher punishments or mandating prescriptions for Sudafed. It's within each and every addict.

If we can learn what makes us vulnerable to addiction and--by talking to those in recovery--what makes some of us finally realize we have to break the cycle of drug abuse, we can learn how to reach susceptible men before they destroy their lives.

Researchers such as Jim Peck are looking for drugs to help ease the harsh withdrawal symptoms that come with giving up meth, but they know there will never be a silver bullet. Recovery is a mysterious mix of rediscovering hope and dedicating yourself to finding new ways of responding to life's ups and downs. It's about coming to terms with your own pitfalls and establishing conscious strategies to sidestep them.

And it's about finding the strength to look euphoria in the eye and say no, thank you.

We've only just begun to learn how to help gay men escape the crystal ship. Activists around the country are testing new campaigns all the time to dissuade their fellow queers from taking that deadly wrong turn. But everyone's journey will be much more productive if we stop a moment to listen to those of us who have already been to the brink and back again, to hear from them the lessons they can offer to those of us still teetering on the edge.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

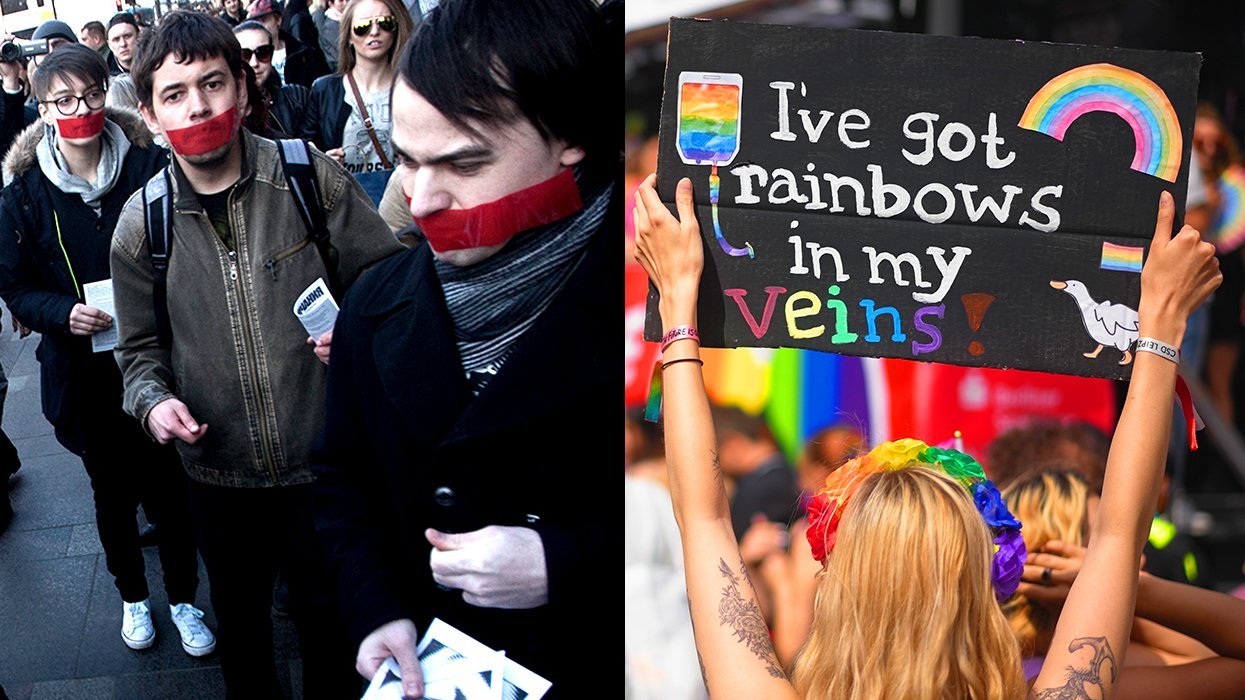

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

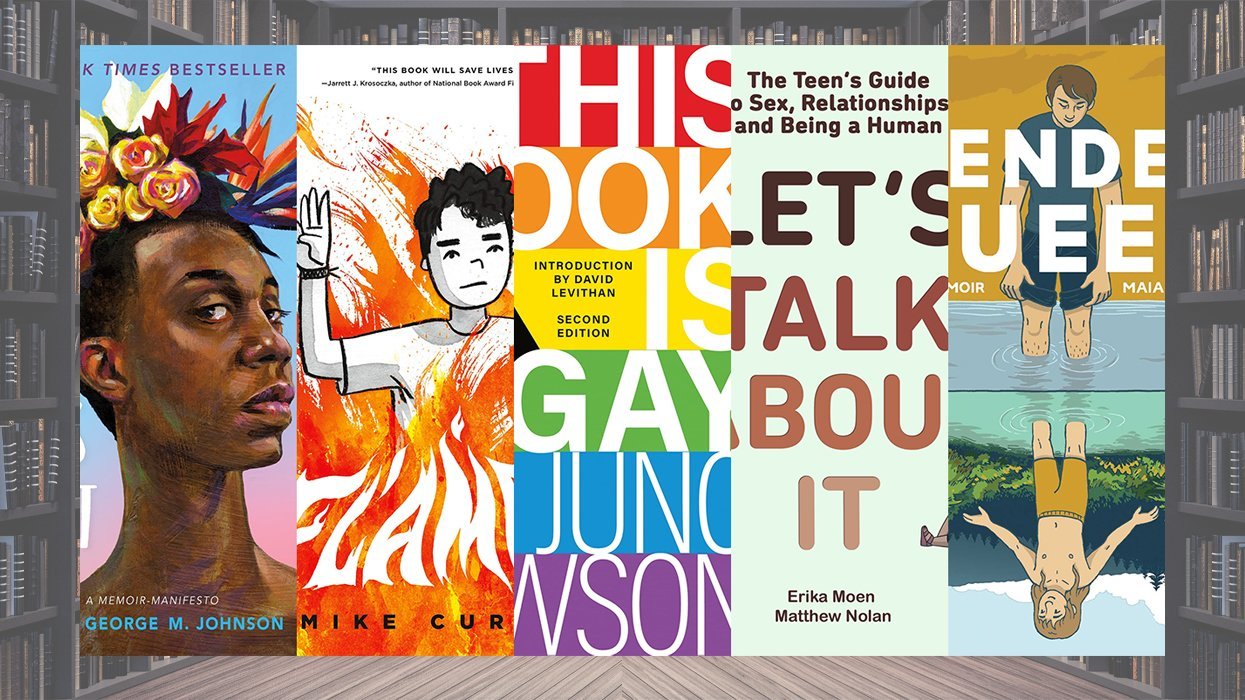

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM

Investigation launched after man screams homophobic slurs at queer couples on D.C. metro

April 13 2024 9:59 AM

Germany makes it easier to change gender and name on legal documents

April 12 2024 6:06 PM

A youth's call to action on this Day of NO Silence

April 12 2024 5:00 PM

Democrats introduce resolution in support of LGBTQ+ youth

April 12 2024 4:35 PM

Colton Underwood is hoping to create a gay reality TV dating show

April 12 2024 4:28 PM

Idaho closes legislative session with a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ laws

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedElevating pet care with TrueBlue’s all-natural ingredients

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Watch Jimmy Kimmel's hilarious LGBTQ+ campaign video: 'You can't spell Biden without Bi'

April 12 2024 12:00 PM

Pride

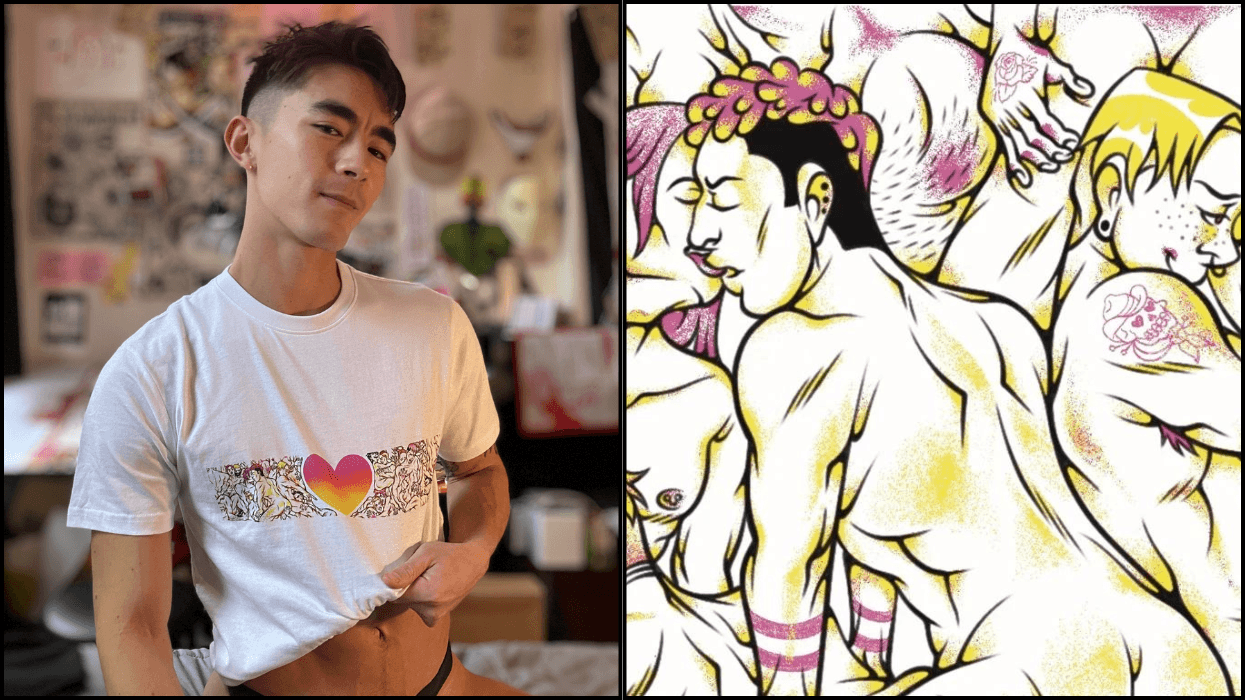

Yahoo FeedCreating erotic art and advocacy with adult entertainer Cody Silver (EXCLUSIVE)

April 12 2024 11:39 AM

How I navigated through religious trauma

April 12 2024 11:00 AM