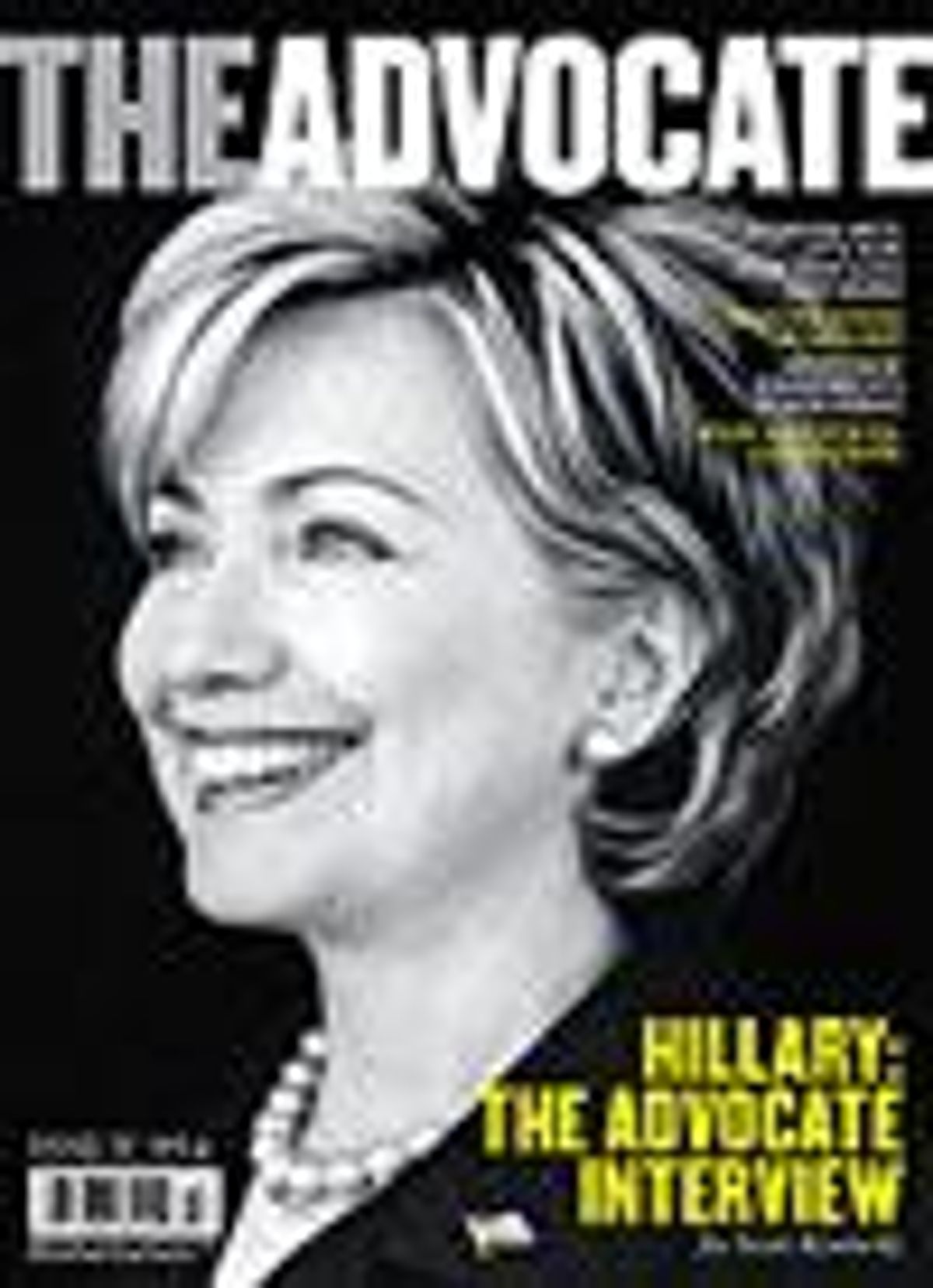

"I come from a

very middle-class background," Hillary Clinton is

telling me. "I consider myself to be pretty much a

typical American, and I think a lot of people my age

and older are really having to think hard. Younger

people are much further along. You just have to keep pushing

that door open."

She's

talking about the gay rights movement, about the

soul-searching it's causing many Americans --

including herself -- but it's typical political

boilerplate: all form, no content. She's not really

saying anything, just bunting back a question about

marriage equality with the least amount of provocation

possible. That's what politicians do, and by

all accounts she's become a great politician.

Yet I find myself

believing everything she says, my natural skepticism

put on hold. I'm enamored with her. She just has that

effect.

Indeed, mere

moments before, she was wowing the crowd at the

Logo-Human Rights Campaign Democratic

presidential forum on LGBT issues in Los Angeles, in

spite of her evasions on same-sex marriage. Maybe it was the

way she looked, resplendent in a coral jacket and chic black

pants. Weeks earlier at the CNN-YouTube debate,

John Edwards, clueless as usual, panned a similar, if

not identical, outfit--though Barack Obama, befitting

his stylish reputation, complimented it--and when

moderator Margaret Carlson, the longtime Washington

journalist, introduced Clinton to the L.A. studio

audience, she good-naturedly exploited the incident for a

joke. "I don't know if Senator Edwards is

still here, but from the last debate, let me go on the

record," she said with a smile. "I like the

coral jacket." On cue, the senator -- and her

audience -- laughed. Clinton chose the last slot on

purpose, and this was why: She was killing without

even talking about the issues yet.

Just why are we

so in love with Hillary? Her husband signed the vile

"don't ask, don't tell" law and

the nefarious Defense of Marriage Act, she refuses to

endorse same-sex marriage even though everyone suspects

she privately supports it, and on other issues important to

us she can sound a little soulless.

Nevertheless,

it's Clinton whom gay voters are carrying the torch

for this campaign season. While Edwards has been

accused by a former political strategist of saying

he's uncomfortable around gay people--and

often looks that way discussing LGBT issues, in stark

contrast to his magnificent wife--and Dennis

Kucinich, Mike Gravel, and Bill Richardson just seem

out of touch (and forget Chris Dodd and Joe Biden, who

didn't show up at the HRC-Logo forum),

she's the one who captured our hearts long ago,

and neither of us will let go. Only Obama has cast a similar

spell, but as much as he's called a "rock

star" (so cliche!), it's Hillary

who's the true megawatt one-named wonder of fame --

and Obama's record on gay issues pales in

comparison to hers.

Sure, to some

gays, as to so many Americans, Clinton is just a

politically calculating, frigid, liberal monster, a

nightmare who won't go away -- her

unfavorability rating, cited with relish by foes,

currently stands at 48%, according to a USA

Today-Gallup poll. But by the end of her

turn in the hot seat that August night in Los Angeles,

it surely wasn't a stretch when moderator Carlson

suggested that Hillary is our girl. "I am your

girl! Absolutely!" Clinton replied, as a wave of

adulation once more ripped through the crowd.

Before I know it

she appears in front of me. Fresh from the stage, she

walks into the nondescript green room with a big smile and

shakes my hand warmly, saying my name. I've

caught her in a rare down moment -- next door a gaggle

of friends and staffers waits, and after this interview she

will head directly to the West Hollywood watering hole the

Abbey, where a viewing party for the forum, doubling

as a Clinton fund-raiser, is to conclude with an

appearance by the candidate herself.

A campaign

staffer told me she was up all night, having arrived in Los

Angeles on an 8 a.m. flight, and she looks it, the lines on

her face pronounced like a road map of the enormous

life she's lived. But even though I can tell

she'd rather put her feet up and kick back, she is a

study in composure, her campaign face on, the gears clicking

in her head. She talks buoyantly, often looking into

the middle distance, and appears to be in a reflective

mood. Yet I know she's just trying to say the right

thing. No mistakes, certainly not with a journalist from the

gay press. Stay on message.

Up close and

personal, I experience Clinton with a kind of double vision.

I have been a fan of hers since the 1992 campaign. I was

just a freshman in high school, and her willful

iconoclasm exerted a powerful hold on my imagination,

my sense of who I could be. I felt a connection with her in

the same way I did with Madonna -- as a suburban kid who

already felt exceedingly different from my peers, I

found their disregard for conventional wisdom

thrilling to behold. Since then, Clinton has continued

to inspire me with her smorgasbord of public identities: the

trailblazer who taught Arkansas a thing or two about modern

women and Washington about political wives. The

wronged woman who, like some country and western

heroine, won't be kept down, whether by failed health

care reform or adultery. A feminist who knows what

it's like to be discriminated against for

simply being who you are. Finally, though her campaign

is loath to talk about it, Clinton is a woman who enemies

have tried more than once to caricature as

"lesbian." So she knows firsthand the

stigma associated with homosexuality.

One of my

strongest images of Clinton is from years before she rose to

national prominence, when she had a brief taste of the

limelight following her impassioned commencement

address to the graduating class of Wellesley in 1969.

She took to task the previous speaker, Massachusetts

U.S. senator Edward Brooke, for being a symbol of political

inaction. "Part of the problem with empathy

with professed goals is that empathy doesn't do

us anything," she said pointedly then. But this

person talking now -- "I come from a very

middle-class background" -- reminds me less of

her idealistic younger self than of Diane Keaton's

neurotic intellectual in Manhattan, who during a

snobby conversation about fine art says, "I'm

just from Philadelphia, you know? I mean, we believe in

God." Woody Allen's character retorts,

"What the hell does that mean?"

In every

presidential campaign cycle of recent vintage, the hopes of

LGBT people have been raised high, only to be

painfully dashed. Like a blushing schoolgirl, we take

the varsity jock's flirtations at face value,

deluding ourselves into believing he's going to ask

us to the prom, when in reality he's just using

us to get to our sexy friend who will actually put

out. The Democratic presidential candidates whisper

sweet nothings into our ear and gladly take our money, but

they never say what we truly want to hear: "We

think you should be able to get married."

It's an understandable impulse -- our hunger to be

recognized is so great that only the president (or a

credible wannabe) can sate it -- but isn't it

asking too much? According to polls, some 60% of Americans

are against same-sex marriage, which means it's

too risky for a presidential candidate to go p there.

Still, with our affection unrequited, we want him or

her to go there anyway.

And Clinton

won't. That she has by far the longest and best

record on LGBT issues -- she's an original

cosponsor of both the Employment Non-Discrimination

Act and the hate-crimes bill currently pending in

Congress; she helped devise strategy to defeat the Federal

Marriage Amendment in the Senate; she's pushed

for expanded funding for HIV and AIDS services; and as

her queer supporters love to point out, she was the

first first lady to march in a gay pride parade -- is a moot

point. She doesn't support same-sex marriage,

arguably the only litmus test that counts anymore for

a politician who really wants our vote. Her Achilles'

heel is so exposed that even my contact at the campaign, the

press officer for specialty media, Jin Chon, pulled me

aside before the interview and tried to persuade me

not to ask Clinton about marriage equality. In a

conference call that morning with two of her policy

advisers, I had apparently asked "a lot" of

questions about the subject. "She's not

going to change her mind about it," Chon told me.

Her verbal

maneuvering on the issue frequently seems like an elaborate

in-joke between Clinton and gays, as if she knows we know

she supports marriage equality personally but that we

understand she has to pretend to be against it

publicly for the sake of winning elections. (Isn't

the general electorate so funny!) During the forum she

resorted to two explanations for not supporting

federal marriage rights for gays: that the states

should "maintain their jurisdiction over

marriage," for which she was roundly

criticized, and that her opposition was simply a

"personal position."

She seconds the

latter answer when I ask her about it -- "It's

probably rooted in my background, like we all are

results of our experience," she says -- but

despite what seems to be sincerity, it's still hard

to take. We're supposed to be convinced that

this brilliant Yale-educated lawyer and lifelong

feminist, who hobnobs in Martha's Vineyard and Malibu

with her well-heeled friends from the business and

entertainment worlds -- who famously declared that

women's rights were human rights at the 1995 World

Conference on Women in Beijing while China was on lockdown

-- is having trouble with the concept of same-sex

marriage?

Could she perhaps

be a closet supporter of marriage equality? Her

"evolution" on the issue has been much

ballyhooed since she said at a private meeting of New

York City and State gay elected officials last year

that she wouldn't be opposed if a pending marriage

bill in the state became law. It was an opinion,

people have noted, she wouldn't have dared

voice in her inaugural run for office seven years earlier.

But there also wasn't a bill then, and poll

results have changed for the better. Then this summer

Clinton came out against the part of DOMA that prevents the

federal government from recognizing states' decisions

on same-sex unions, saying it should be repealed. And

why would she tell me that marriage equality is

something "I'm going to keep thinking about,

obviously" if not to leave room to eventually

embrace it?

But when I

suggest that her "personal position" is

actually not her position at all, she quickly

interrupts me, sitting up in her chair with a start.

"I don't think that would be fair," she

says. "Because, you know, I would tell you

that. This is an issue -- I'm much older than you

are -- and this is an issue that I've had very few

years of my life to think about when you really look

at it, when you compare it to a whole life span. I am

where I am right now, and it is a position that I come to

authentically. But it is also one that has enormous room and

support both in my heart and in my work to try to move

the agenda of equality and civil unions

forward."

It's

anyone's guess how Clinton really feels -- maybe she

is legitimately wrestling with same-sex marriage, who

knows? -- but her supporters are more than willing to

play her game. Later that night at the Abbey, after

Clinton has come and gone, delivering her stump speech to a

thunderous ovation, I talk to two clean-cut

professional guys in their 30s. Police officers are

still patrolling the closed-off street outside, and as the

sign-holding demonstrators -- antiabortion activists,

"Impeach Bush" types, Hillary fans --

start to pack up, the men cite the usual reason for

supporting her: her experience. But they also tell me

they're disappointed by her position on

marriage equality.

"She has

the ability to lead on this issue, but for whatever reason,

she's not," says one. Then he whips out his

digital camera and excitedly shows me the photos

he's just taken of her. "We were right by the

velvet rope!" his friend squeals, referring to

the club world staple that held back the senator from

rabid admirers like them.

The Clinton

acolytes who know her well point to another reason to vote

for her: her pure comfort level with gay people. Fred

Hochberg, the head of the Small Business

Administration under President Clinton and now the

dean of the business school at the New School in New York,

has known Hillary since the 1992 campaign, when he

raised funds for her husband. He sits on her

campaign's LGBT steering committee, cannily launched

on the eve of this year's Stonewall

anniversary, and he talks admiringly not only of the

"hard work" she's done behind the

scenes, such as organizing meetings of the Senate

leadership on LGBT issues, but also of her

"enormously relaxed" vibe at the HRC-Logo

forum -- and with Hochberg and his partner, Tom Healy.

"She's one of the very few people in life, let

alone public life, who will unfailingly always ask,

virtually the first question, 'How's Tom?

What's he doing?' " Hochberg tells me.

"She was at an event for the New School, and as

I said goodbye she said, 'Make sure to give Tom a hug

for me.' That kind of expression feels

personal, genuine. Not a lot of people do that period,

let alone a sitting senator or first lady. It's

unique among faculty members. I'm dean of the

school, and they don't ask me about my

partner!"

Hochberg also

recounts a fascinating story: that when Clinton's

father died of a stroke in 1993, her parents'

gay male neighbor came to the hospital to be with the

family. "I introduced her at a fund-raiser in

Washington, and Hillary spoke very eloquently about

that," Hochberg says. "That's a

deeply personal experience any of us endures, the loss of a

parent, and the person that was with her father was her

mother and father's gay neighbor. She just made

that part of the story of her life -- I think

that's meaningful."

Neel Lattimore,

who served as press secretary to Clinton for five years

when she was first lady, has similarly warm and fuzzy

anecdotes to share. When he was promoted to the highly

visible job, Lattimore took Clinton aside and told her

he was gay, just so she would know in case any of the

Clintons' numerous political foes wanted to make an

issue of it. The conversation in the Map Room turned

into a heart-to-heart. "I said, 'I want

to be a good role model for my nieces and nephews --

there's not a lot of role models out there for

gay men,' " he remembers. "I thought

that was a perfectly logical thing to say. But she was like,

'Who are you running around with?' I

said, 'Excuse me?' And she said, 'If

you don't find some people that you consider to

be role models in the next several weeks, come back to

me and I'll introduce you to some.'

"That's when it was clear that she had friends

who were gay," he says. "If I was

struggling to find people that I could look up to, she was

like, 'I'll give you a list, I'll set

up some meetings. You can feel good about

this.' "

Several years

later, no longer in her employ, Lattimore held a

fund-raiser for her New York Senate campaign at

Washington's Mayflower Hotel, attended largely

by gay friends of his. It was a campy affair --

"We're showing pictures of her with bad hair

on the screens, and she's just

laughing!" -- but the tone turned downright mushy

when Lattimore introduced his mentor to the crowd.

"I told the story about the role models, and I

said, 'Mrs. Clinton, I want to introduce you to my

role models.' " He pointed to the 500

guests in the room. "And I heard her very

quietly in the back go, 'Oh, Neel.' "

His memories

aren't all so serious, though. Speaking of her hair,

for instance, Lattimore--the only man in

"Hillaryland," as her devoted staffers

call their private world--was often called upon for

certain styling tasks. "I'm telling you,

when you travel around the world on a small plane full

of women and you're the only man, yes, you take

curlers out of hair!" he says with a laugh.

Indeed, that

Clinton is a woman cannot be underestimated in her appeal to

gay people, and vice versa. Bill Clinton often spoke of a

"politics of compassion," but Hillary is

the one who has lived the struggle for respect and

equality just as gays have. That common experience informs

not only her personal solidarity with us but also her sense

that the fight for marriage equality is by necessity a

long-term proposition, something that can't be

won overnight.

"When I

was a young woman there were colleges I couldn't go

to; there were jobs I couldn't have

had," she tells me. "But I tried to live my

life as fully as possible, even though I wasn't

always supported in the rest of society."

She's

quick to point out that the first time women publicly

claimed the same rights as men was in 1848 and that

they didn't win the right to vote nationwide

until 1920. "We didn't get written into our

Constitution because the Equal Rights Amendment was

effectively demonized by the right," she says,

sounding a familiar note in these Roveian times.

"The gay

rights movement has been unbelievably successful over a

relatively short period of time. I know that if

you're in the midst of it" -- here she

smiles, brightening -- "you see the failures to move

forward, not how much forward motion has occurred. The

lesson is to keep going, don't give up. Know

that you're laying the groundwork for people

being more understanding and accepting. But just keep

going."

For her to become

the first woman president, she knows, could only

benefit gay people. "I think it would be

huge," she says. "For too long the right

wing has tried to pit marginalized groups against

marginalized groups and basically have a zero-sum game

in American political life. And if I can break this

barrier, I think it really lets the energy come out.

People will feel that there's a greater inclusion --

and that they're a part of that

inclusion."

Clinton's

pioneering ways have, of course, met with fierce resistance

in the past. Her detractors are legion, and many

people simply hate her for being a powerful woman. The

animosity is such that as soon as her husband was

inaugurated in 1993, rumors started circulating that she was

a lesbian, Lattimore recalls. "Where that came

from, I just could never figure out," he says.

"It was so ridiculous." One man would call the

press office repeatedly, posing as a reporter for different

newspapers, seeking comment on his scoop that Clinton

was gay. Lattimore eventually transferred him to the

Secret Service, letting them deal with him.

"I never

talked to Mrs. Clinton about it, but we had to be responsive

to that question in a way that didn't make it

sound like being a lesbian was a bad thing," he

says. "No, she's not a lesbian, move on. Next

story."

If she

wasn't aware of the speculation then, she surely

heard about it when author Edward Klein brought it to

the surface in his 2005 smear job The Truth About

Hillary, in which he dubiously asserted that "the

culture of lesbianism has influenced Hillary's

political goals and personal life since she was a

student at Wellesley."

No one is ever

courteous enough to ask Clinton directly how she feels

about the lesbian chatter. So I do.

"People

say a lot of things about me, so I really don't pay

any attention to it," she responds.

"It's not true, but it is something that I

have no control over. People will say what they want

to say."

The most

poignant moment of the HRC-Logo forum was when Melissa

Etheridge, redeeming herself after one too many asinine

questions about bark beetles and other unrelated

esoterica, pressed Clinton on her husband's

failures in office. For better or worse, the two are

inextricably linked, and his record affects perceptions of

her. With Hillary Clinton in the driver's seat

at least for the time being, a field of Democratic

candidates uniformly good on gay issues, and a long,

divisive period of Republican rule seemingly about to end,

it's been hard not to think back to that

equally heady moment 14 years ago, when Bill

Clinton's inauguration positively radiated promise.

His tenure in office, however, was not all that we had

hoped it would be. On "don't ask, don't

tell" and DOMA, he definitely let us down.

"Our

hearts were broken," Etheridge said. "We were

thrown under the bus. We were pushed aside. All those

great promises that were made to us were broken. And I

understand politics. I understand how hard things are, to

bring about change. But it is many years later now, and what

are you going to do to be different than

that?.... A year from now, are we going to be

left behind like we were before?"

Clinton politely

sidestepped a response -- "Well...Melissa, I

don't see it quite the way that you describe,

but I respect your feeling about it" -- yet the

question still lingers: Would she leave us behind?

In many ways the

Clintons were my first love. When I was growing up

during the 12-year Reagan-Bush reign, the Republican

political landscape was all I knew. Gay people were

still feared. I hadn't come out to myself. And

then this fresh-faced, passionate, progressive couple with a

commitment to change and a vision of hope emerged from the

ether and changed all that, charming me along with the

rest of America. But like all infatuations, this one

was too good to be true. Slowly but surely I was

disillusioned.

Yet isn't

that why politics often seems so much like romance, why we

fall for politicians time and time again, only to be

forcibly shown the limits of our dreams? "You

have to realize you are empowering them to hurt you,"

Lattimore tells me in an aside. Indeed, the higher the

expectations, the harder the crash.

As any good

therapist would say, no partner is perfect. At least

Clinton's willing to try. "I cannot promise

results," she says to me. "I can only

promise my best effort. I can only promise to do everything

that I can do to make the case, to put together the

political majority, to take the message to the

country, and I will do that. But there are no

guarantees in life or politics."

So, I say to her,

even if the negative feedback is deafening, would you

still push forward on repealing "don't ask,

don't tell"? "I'm certainly

going to continue to push forward," she says.

"But again, I can't guarantee that the

negative feedback will go away. The president is not a

king, despite George Bush's efforts to be

one...and don't forget, there's

another set of agenda items too. We've got ENDA and

hate crimes."

"If they

reached your desk," I press, "you'd

promise to sign them?"

"Absolutely, because as president I would be trying

to get them to my desk," she says with an

exasperated laugh. "That's the whole

point!"

She sounds like

she means it, like the filter is off for once, and I

believe her -- I really do. But as I write this, several

weeks later, I still don't know. Commitment is

so hard. Do I want to get in bed with Hillary again? I

take a deep breath. If a relationship is about trust, I

guess she has mine.