CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

The brightly covered DVDs were for sale everywhere. A walk along the streets of Mazar-i-Sharif, a major city in the north of Afghanistan, revealed one vendor after another selling recordings of young boys dressed as women. The cover photos showed them surrounded by crowds of men sprawled on carpets, clapping, throwing money, cheering them on.

I saw these back in 2004.

PBS's Frontline just aired a major show on the Afghan dancing boys, or bacha bazi, perhaps the largest mainstream investigation into the issue, with reporting started in 2008. I first heard of them in 2003, from Afghan-American friends before my first visit. The ritual, which has existed since ancient times, is still practiced in the country's remote north. My friends hesitantly discussed the age imbalance between the dancing boys, usually poor orphans, and the men, often powerful commanders, who hired them to perform at weddings where attendants are separated by gender. The boys fulfilled the role of women yet didn't violate gender separation rules. That sex occurred between the boys and men was tacitly understood. That same year, at the U.S. embassy in Kabul, a local staff translator told me about the issue in greater depth, saying he'd even heard of ceremonial marriages between the boys and the men who kept them.

It seemed too fantastical. In fact, virtually no editor in New York to whom I told the story believed me, whether at gay or mainstream publications. Some thought I had to be making it up. Frontline has finally proved that is not the case.

Yet years before Frontline, I knew I had to investigate and visit Mazar. A stronghold of the U.S. ally Northern Alliance, it was one of the last cities to fall to the Taliban. Ethnically, most of its residents are Tajiks, and there are Turks, Uzbeks, and other groups. The city is dominated by the exquisite Blue Mosque, said to be the shrine to Hazrat Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad.

I was warned the topic was taboo, but the availability of the DVDs meant that was far from the truth. It was also not difficult to find people to connect me to the dancing parties. My goal was to photograph and interview the boys about their lives.

It was easy to broach the subject with the English-speaking son of the owner of my hotel. The dancing was illegal in the city, he said, but he took me to the bazaar where I could meet men who sold costumes. An important element was the zang, meaning "bell" or "ring sound" in Dari, the Afghan language in the north. The zang were anklets and bracelets with tiny bells, which gave off rhythmic sounds as the boys danced. If you've seen The Kite Runner, the movie based on the novel by Khaled Hosseini, the bells are in the scene where the main character rescues the orphan. The boy is wearing them as he dances for a man planning to sexually abuse him. Selling the bells was illegal, I was told, but these, like the videos, were everywhere in the bazaar.

Find the zang, and you've found the men arranging the boy parties. One introduced me to a musician, who had a large turban, a black beard, and heavy lines across his face. He was well-known in Mazar; his recordings are available in the same places I bought the zang. Married with children, he had two sons he was training to be musicians. And he could arrange parties.

Word had gotten around about my plans, something that was still fraught with danger, in spite of the seeming openness. Looking into dancing could be a challenge to some of the most powerful commanders in the city, many of whom hired the boys for their parties.

Many men also made assumptions, thinking my interest went beyond journalistic. When one bazaar merchant came to talk to me at my hotel, I clearly remember him on the staircase telling me he could not wait for the weekend, so he could be "fucking boys." The sinister way he began to laugh made me worry what I had gotten myself into. The hotel owner threatened to throw me out, worried the authorities would come after him, but I was able to assure him I only wanted to photograph at the party. Still, he forbade his son to translate for me.

The musician told me that to see a party, we would have to venture far from Mazar, to remote villages where the law didn't hold sway. Along with several of his musician friends, we loaded into a van and began a dusty journey that lasted hours. I wondered when we would be back in Mazar, and it was only on the road that he explained that the area was too dangerous at night, full of insurgents, and we would stay overnight where the party took place. The dangers explained why one friend carried a portable rocket launcher.

We entered deep poppy-growing territory; children with bundles of the plants like bouquets were on the sides of the road. It was beautiful and tragic all at once, but I was too afraid to ask to stop and photograph. In the village the roofs of the mud houses were piled with poppy plants drying in the sun. The musician took me into the fields, presenting me with a rose, and asking me to rest on a carpet-covered platform where men gathered to talk. By nightfall I found I'd been duped. The musicians were performing for a welcome-home party for a man who had returned from Russia. There would be no dancing boys for me to photograph and interview. Still, I made the most of the evening. It was the first time I had been in so remote a village. When the party ended, we slept under thick blankets in an open courtyard under the stars. I was told it was an honor to sleep next to the musician, but I could not fall asleep.

Back in Mazar, the musician demanded I pay the cost of transport to the party. Only the intervention of a local Afghan journalist friend resolved the problem. He too had been curious to write about the dancing boys, and he decided to look into it with me.

After a few phone calls, in the evening, we met another group of musicians. Mazar might be one of Afghanistan's largest cities, but it's a small place. My friend knew many of the men there. Still, all did not go as planned. We were told there were several dancing parties that evening, a few thrown by the most powerful commanders. I began to wonder if there were conscious efforts to thwart my attempt to cover the dancing boys. Our dancer was in his early 20s, someone who had been dancing since he was 14 or 15. He was not in the proper clothing for the dance either, other than zang on his ankles, the commanders having made sure the best costumes were at their own parties. I'd been told that up to this point in 2004, no Western journalist had photographed a zang dance. The commanders seemed to want that to remain the case.

My journalist friend explained what I was looking at that evening, telling me which of the musicians was famous for playing at the parties and who in the audience pimped out boys. No one seemed to mind my photography.

As he took a break, I interviewed the dancer. He was an orphan, taken under the wing of a man who trained him at the age of 13 or 14; otherwise he would have been homeless, unable to support himself. Now in his early 20s, he knew he was at the end of his dancing days, in spite of his efforts to appear youthful. The local journalist explained it would be hard for him to lead anything resembling a normal life. He would be unable to marry and join proper Afghan society. The young man told me of the gifts men bought him, how money would be thrown at him at parties. There was a broad smile on his face as he reminisced about earlier days when he garnered more attention. When I asked, through the local journalist, if he had sex with the men who bought him things, he answered no.

My friend said not to believe him.

I left Mazar the next day, returning to Kabul. I would learn more from friends there about young boys who would be kidnapped to be turned into dancing boys. Some would be shut away in dark rooms for long periods of time, a way to lighten their skin and keep them docile. Watermelon juice baths were used to keep their skin soft and boy-like. I would also be contacted by a human rights researcher looking at the trafficking of Afghan girls sold by their families. She found out about the boys too, kidnapped and forced between the Afghan and Pakistani borders. Finding articles I had written on gay Afghanistan, she reached out to me, explaining she had trouble getting journalists to cover the topic. I was saddened to tell her my experiences with editors.

I eventually put forth a book proposal on my travels through Afghanistan, which included my visit to Mazar. Few publishers wanted to touch it. Some even worried about fatwas and terrorist attacks on their offices. I gave up on that particular project.

Looking back, perhaps I was naive. How deeply could someone like me, unable to speak Dari, cover the subject? I am glad that Najibullah Quraishi was able to convince Frontline to look at the topic. I am also happy that at least for the boy he interviewed there is a happy ending. Watching the show, my heart would beat in anger and my stomach would churn, because of the fate of these young boys.

During my visits to Afghanistan, I found there is same-sex love on a more equal footing between men of the same age, it too at times resulting from the separation of gender and fluidity of sexuality of a homosocial space. Dancing boys, though, are an exploitation of the poverty of orphans forced to fend for themselves. The problems are the same as those of marriages between old men and underage girls, just with a gender change.

Afghan-American friends of mine are repulsed by these dances. One who runs a server list sent a note telling his members to prepare for the questions they'll receive wondering if all Afghan men seek out sex with young boys. The answer is no. Still, within the remote regions and impoverished areas, this remains a huge and painful phenomenon and incredibly visible.

With the U.S. reengaging in Afghanistan, with, I hope, an emphasis on human rights issues, only time will tell how much this subject is looked at. My only question, thinking back to 2004, is why did it finally take so long for someone to believe this was happening?

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

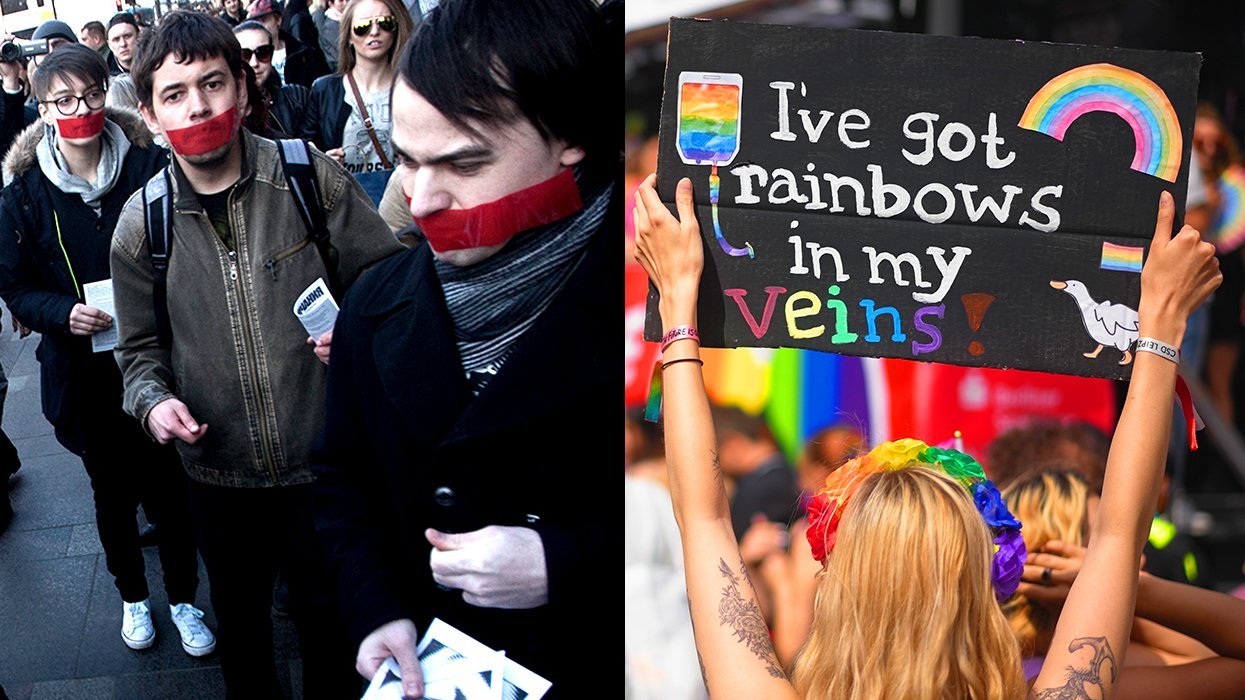

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

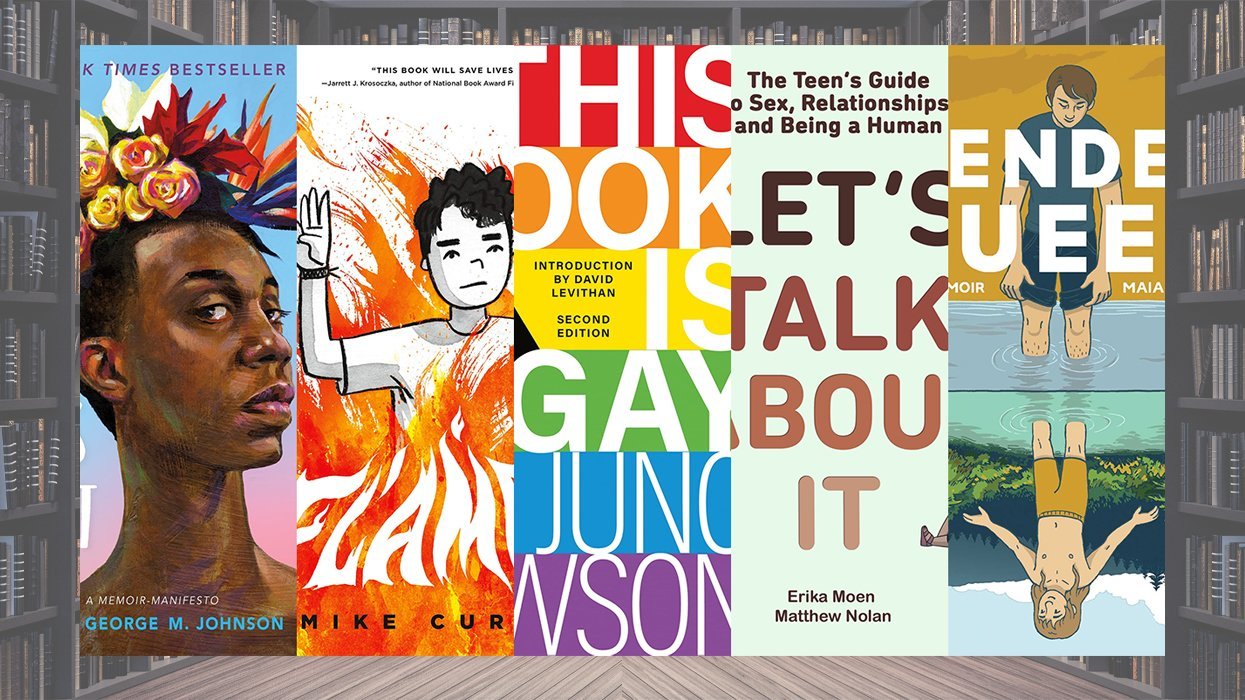

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM

Investigation launched after man screams homophobic slurs at queer couples on D.C. metro

April 13 2024 9:59 AM

Germany makes it easier to change gender and name on legal documents

April 12 2024 6:06 PM

A youth's call to action on this Day of NO Silence

April 12 2024 5:00 PM

Democrats introduce resolution in support of LGBTQ+ youth

April 12 2024 4:35 PM

Colton Underwood is hoping to create a gay reality TV dating show

April 12 2024 4:28 PM

Idaho closes legislative session with a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ laws

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedElevating pet care with TrueBlue’s all-natural ingredients

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Watch Jimmy Kimmel's hilarious LGBTQ+ campaign video: 'You can't spell Biden without Bi'

April 12 2024 12:00 PM

Pride

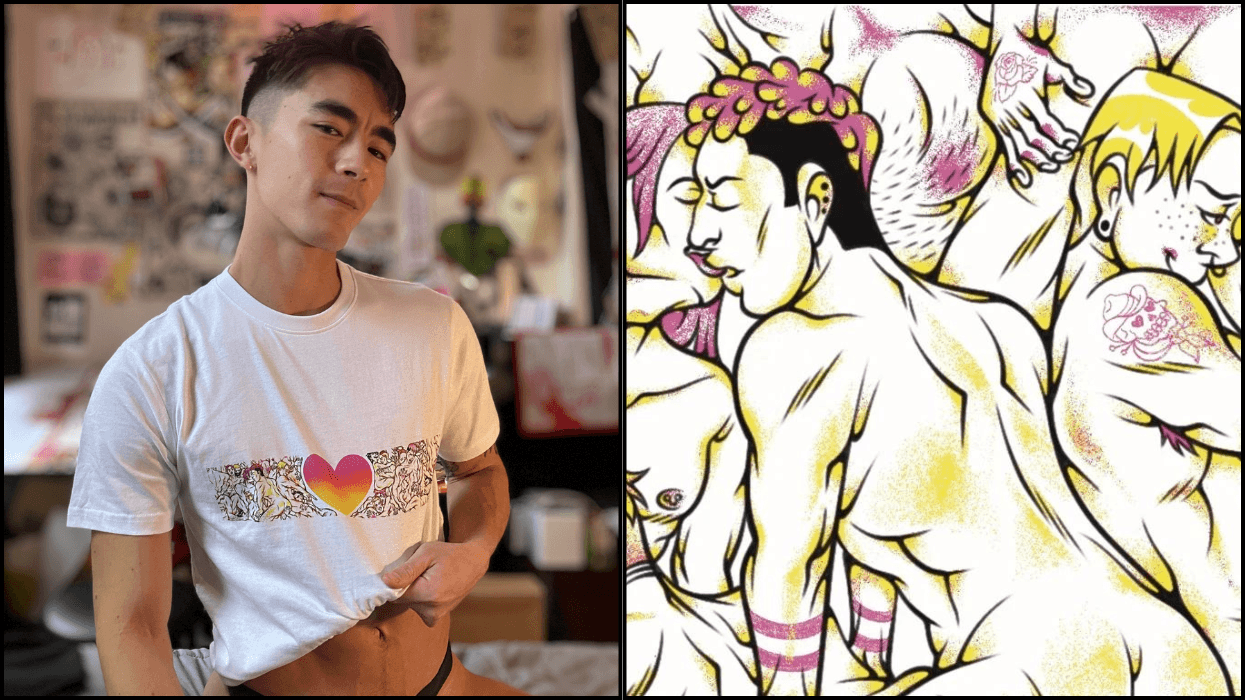

Yahoo FeedCreating erotic art and advocacy with adult entertainer Cody Silver (EXCLUSIVE)

April 12 2024 11:39 AM

How I navigated through religious trauma

April 12 2024 11:00 AM