CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

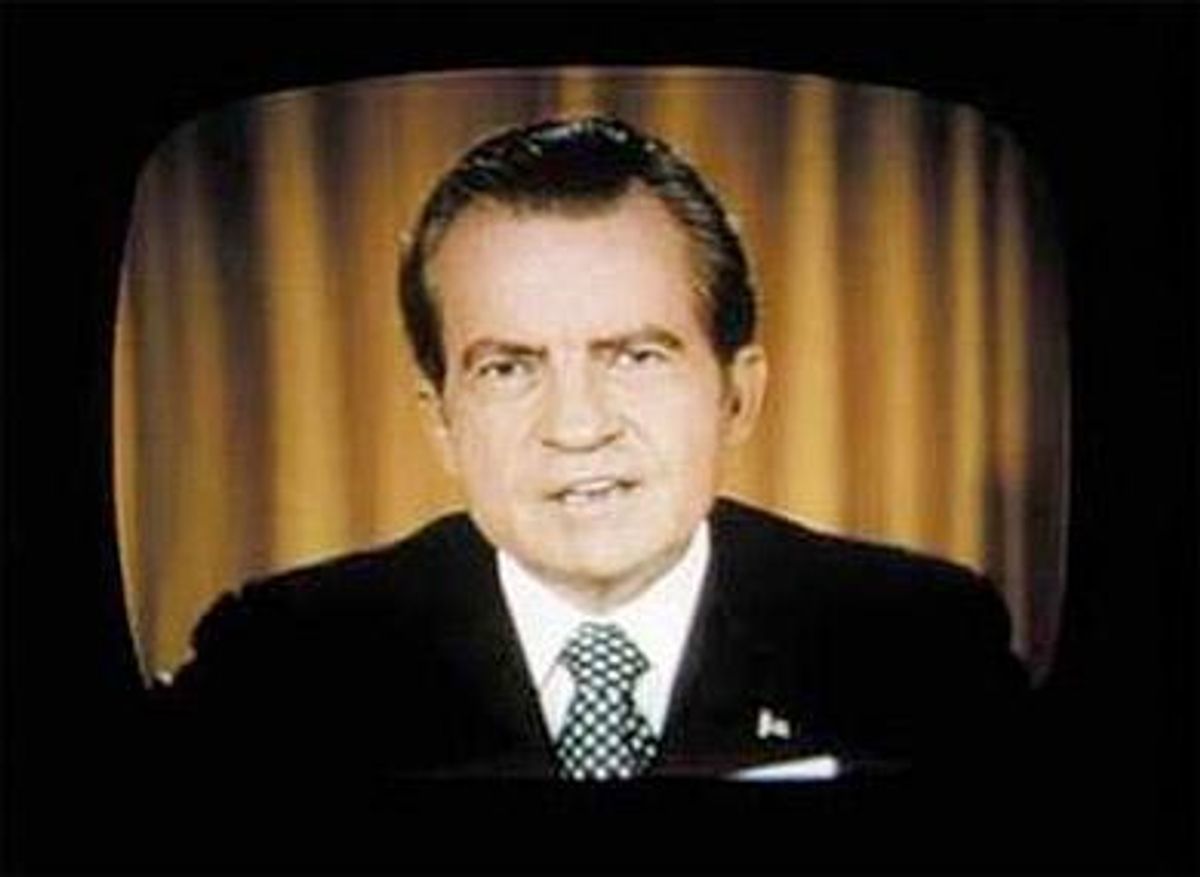

A new book Watergate Exposed is the story of Robert Merritt, a confidential informant to the FBI and D.C. Police (as told to by Doug Caddy), telling the story of one of the nation's biggest scandals through the eyes of the local gay community.

Merritt says he learned about the planned break-in at the Democratic National Committee located in the Watergate complex two weeks before it occurred. His source was James Reed, also known as Rita Reed, a drag queen who worked on the switchboard at the Columbia Plaza Apartments just blocks from Watergate. Reed, a close friend of Merritt, overheard the planned break-in being discussed while secretly listening in on a telephone conversation by two parties conducted through her switchboard.

Rita told Merritt what she heard on June 1, 1972. Two days later, Merritt reported the news to Detective Carl Shoffler, Merritt's lover who also recruited Merritt as an informant for the police and the FBI two years earlier. Shoffler, in reality a military intelligence agent assigned to the D.C. police, immediately devised a clandestine wiretapping plan using triangulation to set up the burglars and also to bring down President Nixon, who claimed to have had had no prior knowledge of the break-in. His cohorts included a retired CIA agent and another U.S. intelligence agent.

Shoffler arrested the burglars inside the DNC's offices in Watergate on June 17 and was immediately hailed as a hero. His entrapment role in setting them up was never revealed. He told Merritt that if he ever opened his mouth about what he knew, he would be killed. Merritt later became a fugitive from justice but continued to receive orders from Shoffler for the 18 years he lived in New York City while working as a confidential informant for the New York Police Department, FBI, and U.S. Attorney, all of which remained unaware of his "wanted' status.

It was The Advocate's article about Caddy in 2005 and a lengthy interview with Merritt in 1977 that prompted a collaboration on their two Watergate stories. The following is the book's foreword, written by Caddy from Watergate Exposed:

There is no single answer. There are many. First and foremost is that Merritt would have been killed if he attempted to reveal all he knew of the origins of Watergate while Washington, D.C. police detective Carl Shoffler, the officer who arrested the burglars, was alive. It is that simple. Shoffler, to whom Merritt confided his prior knowledge of the planned break-in at Watergate two weeks before it happened, also recognized his own life was on the line. As recounted by Jim Hougan in his 1984 best-seller, Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat and the CIA, Shoffler told Captain Edmund Chung, his former commanding officer at the National Security Agency's

Vint Hill Farm Station, that if Shoffler "ever made the whole story public, 'his life wouldn't be worth a nickel'."

After the Watergate arrests and ensuing controversy, Shoffler went to great lengths on many occasions to impress upon Merritt the necessity to remain silent. In the two years before Watergate, Shoffler and the FBI had directed Merritt as a Confidential Informant to commit hundreds of crimes, all done in the name of "national security." Shoffler threatened Merritt that, on the basis of these crimes alone, both of them could be prosecuted and imprisoned, as would certain FBI officials and agents.

Another factor was Merritt's open homosexuality. Watergate occurred only three years after the Stonewall riot, which marked the beginning of the gay rights movement. Homophobia still reigned supreme. Shoffler told Merritt that his homosexuality would be used to discredit him and to railroad him into incarceration. Indeed, as Merritt prepared to enter the building to testify in executive session before the Senate Watergate Committee, a Democratic committee staff member, Wayne Bishop, stopped and told him his credibility was zero because he was a homosexual and threatened that if he told what he knew about the origins of Watergate, he would be immediately thrown into the U.S. Capitol Building's jail. Even the Republican in the White House, Richard Nixon, whose presidency could have been saved had Merritt disclosed what he knew, railed at the time against homosexuals. As revealed in a new book by Mark Feldstein, Poisoning the Press, Nixon wanted so badly to discredit, or even prosecute, newspaper columnist Jack Anderson, that he contemplated an investigation to see if Anderson was a homosexual, even though Anderson was married and had nine children. Nixon Aide H.R. Haldeman is quoted on a tape of an Oval Office meeting with the president as asking, "Do we have anything on [Anderson aide Brit] Hume?... It'd be great if we could get him on a homosexual thing." In support of the witch hunt, another top aide, Charles Colson, ignorantly chimed in, "He sure looks it."

So the overt and widespread hatred of gays during this period was a key factor in Merritt's decision to keep quiet. He only had to look at what happened to me to see what fate might lay waiting for him. In the first month of the Watergate case, Chief Judge John Sirica falsely accused me of being a "principal" in the Watergate break-in crime. Sirica then held me, as attorney for the seven defendants, in contempt of court and ordered me jailed after I asserted the attorney-client privilege and Sixth Amendment right to counsel in behalf of my clients.

Sirica's vicious homophobia was matched only by the judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, who upheld his contempt citation of me in a gratuitously insulting decision. This unreported segment of Watergate - how these prejudiced judges attempted to set me up and destroy my legal career because I was gay - is told in my Epilogue to this book. They ultimately failed because there was not one scintilla of evidence that I was involved, which is why I was never indicted, named an unindicted conspirator, disciplined by the bar or even interviewed by the Senate Watergate Committee.

Despite the pressure to keep him quiet, Merritt on a number of occasions came close to disclosing what he knew about the prior knowledge of Shoffler and certain agents of the intelligence community of the planned break-in. This is covered in Chapter 6, "A Series of Missed Opportunities: How Watergate Might Have Turned Out Differently." In each instance, for one justifiable reason or another, Merritt decided that the best strategy was to lie low about his total involvement: remain quiet about all that he knew. From 1985 to 2000, Merritt was a "fugitive from justice," as he recounts in his story, even though during this period Shoffler continued to direct his activities from afar while the former worked closely as a Confidential Informant with law enforcement agencies in New York that were unaware of his wanted status. As a fugitive, Merritt's goal was not to get caught. Talking publicly about what he knew about Watergate was out of the question.

In 1994 Shoffler died. After 2000, when the Government dismissed the criminal case against him, Merritt could give his full attention to disclosing the untold story of Watergate's origins. He began to collect documents and information that would support his story, an effort that took years. Even so, the FBI has steadfastly refused to release over 300 documents from its files on Merritt, requested under the Freedom of Information Act - documents that could contribute mightily to understanding what occurred.

In May 2008, Merritt contacted me to ask if I would help him write a book about what he knew. I agreed to do so. About the same time doctors who had been treating him for serious medical conditions told him that he had only three to four years to live. This knowledge spurred him to concentrate on getting his book finished. Even as I write this, I have learned that Merritt's doctors told him within the last week that he likely has three to four months to live due to advanced cancer of the spine. They set the outmost date as Valentine's Day 2011.

This book is being rushed into print in order that Merritt can publicly answer questions that might arise while he is still capable of doing so. In a sense his story is a "deathbed confession," as his only desire at this point in time is that the historical truth about Watergate be told fully and accurately.

--Doug Caddy

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

Meet all 37 of the queer women in this season's WNBA

April 17 2024 11:24 AM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

Tristan Snell, who brought down Trump University, sees conviction in hush money case

April 22 2024 7:36 PM

Joe Biden admin marks Earth Day with major environmental initiatives

April 22 2024 4:18 PM

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott: 'We want to end' trans and gender nonconforming teachers

April 22 2024 4:13 PM

Nonbinary 17-year-old killed two years after being reported missing

April 22 2024 3:46 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedIndulge in luxury and sensuality with The Pride Store’s Taurus gift guide

April 22 2024 11:46 AM

The gay man leading the Earth Day Initiative offers hope for the future

April 22 2024 9:00 AM

Pattie Gonia takes drag and fierceness to Capitol Hill to voice environmental concerns

April 22 2024 8:23 AM

Jodie Foster leaves her mark in cement at L.A.'s Chinese Theatre

April 22 2024 7:55 AM

Climate change has a bigger impact on LGBTQ+ couples than straight couples. Here's how

April 22 2024 7:42 AM

Iraq postpones vote on bill punishing gay sex with death

April 20 2024 1:31 PM

Russian poetry contest bans entries from transgender poets

April 20 2024 1:25 PM

Here's who won 'RuPaul's Drag Race' season 16

April 20 2024 1:01 PM

The Tip Off: A beginners guide to the WNBA

April 20 2024 11:06 AM