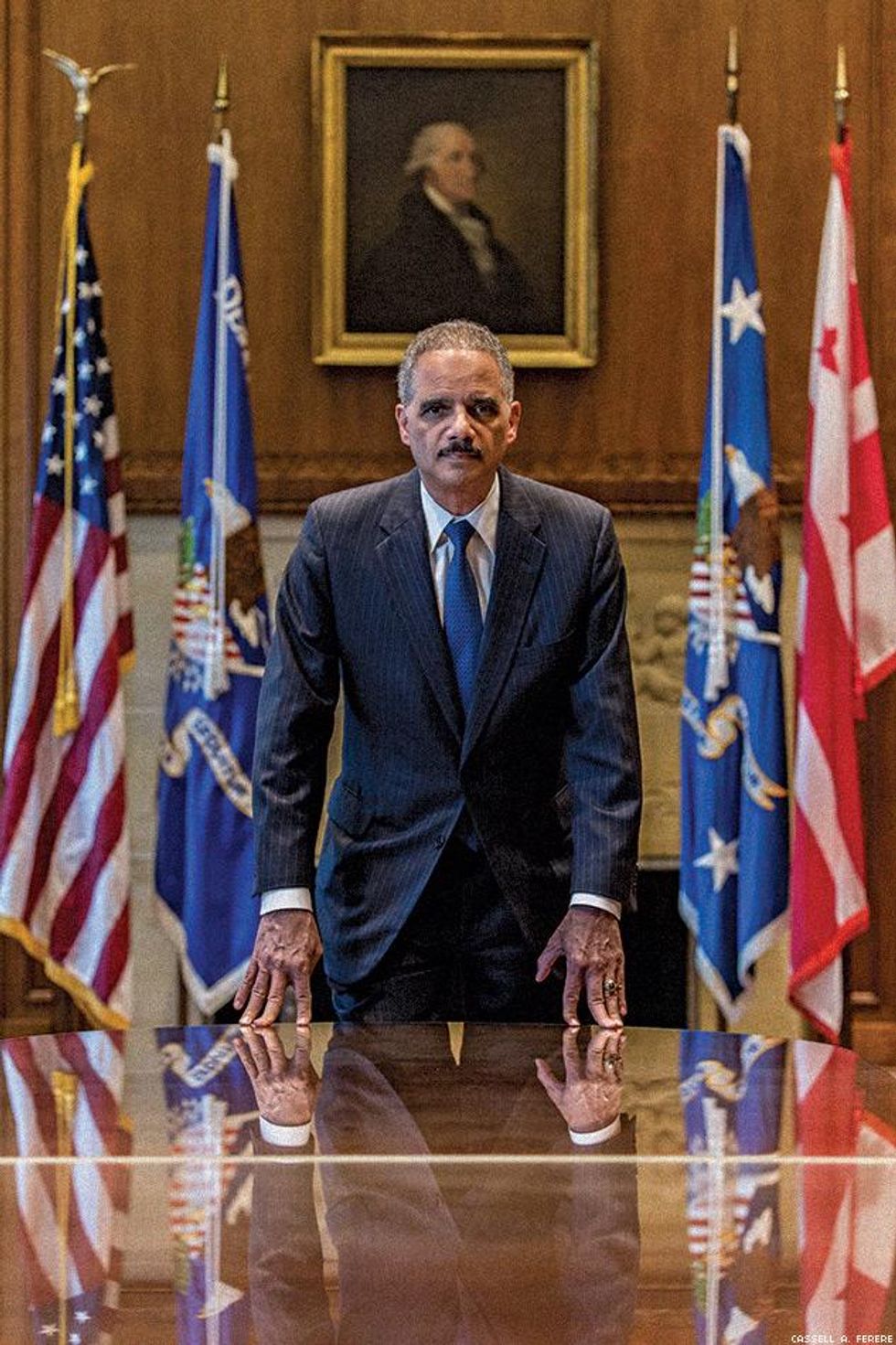

If politics is the art of the possible, then law should be the art of what is necessary. Eric Holder, the first African American to hold the office of attorney general of the United States, made history by redefining what is both possible and necessary.

When Holder took office in 2009, the U.S. military ban "don't ask, don't tell" was still firmly in place, and only two states, Massachusetts and Connecticut, allowed same-sex couples to marry. But during President Obama's tenure, in the attorney general's own words, there has been "a seismic shift."

As Holder leaves office this year, gay and lesbian Americans can now marry in 37 states (and counting). We can serve openly in the U.S. military and are protected against hate crimes under the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, the first pro-LGBT federal law in U.S. history. The number of openly gay judges on the federal bench has increased exponentially. And in part because of Holder's decision in 2011 to cease defending the constitutionality of Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, following the landmark Supreme Court decision in United States v. Windsor, gay and lesbian couples can now receive federal marriage benefits.

The Obama administration's legacy on LGBT rights is historic, as are the often complicated strategies crafted by this attorney general that were needed to solidify these achievements.

Holder has been the architect of a skillful plan to place LGBT rights at the forefront of the administration's civil rights agenda. As the nation's foremost legal advocate, he is tasked with ensuring that all Americans are treated equally under the law. And this is a responsibility he does not take lightly.

But for Holder, the work is not just political, it's personal.

In 2012, two former Republican attorneys general, Edwin Meese and John Ashcroft, criticized Holder's decision not to defend Section 3 of DOMA, saying it was "an unprecedented and ill-advised departure from over two centuries of Executive Branch practice" and "an extreme and unprecedented deviation from the historical norm." But Holder seemed more emboldened this year when the Department of Justice filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in March flatly denouncing state-wide bans on same-sex marriage as being a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution's 14th Amendment.

In his historic announcement he wrote:

"A marriage ban written into state law broadcasts the state's view that same-sex couples and their children are second-class families, undeserving of the rights and protections offered to opposite-sex couples. It creates a stigma that pervades society, encouraging individuals to harass or belittle even their loved ones because of pressures brought by their community. And it harms relationships between family members by perpetuating a destructive notion that some individuals--and some children--should be shown less love and support simply because of who they are. That is a view the Department of Justice flatly rejects. And with our brief, we will make clear that the United States stands firmly on the side of equality."

Holder takes pride in the fact that two heterosexual, African-American men -- namely, President Barack Obama and he -- have emerged as strong political proponents of equal rights for LGBT Americans in the 21st century. He provides a blueprint for what must be done to solidify the progress already made for gays and lesbians and to expand those rights fully to transgender Americans. Holder sheds light on conservative tactics that use "religious freedom" as a way to undermine that progress, and he warns against complacency in the fight for civil rights for LGBT people by reminding us of how women's reproductive freedoms and the Voting Rights Act have both endured backlash more than a generation after they were first enacted.

Above: Holder with members of DOJ Pride

Above: Holder with members of DOJ Pride

The attorney general recalls the landmark 1967 Supreme Court case of Loving v. Virginia, which ended miscegenation laws forbidding marriage between blacks and whites, and tells The Advocate that the fight for LGBT equality is the natural, evolutionary next step in the civil rights movement.

Quoting Mildred Loving, the plaintiff in that watershed case, Holder says, "That's what Loving, and loving, are all about."

The Advocate: I want to begin with the announcement from your office outlining the federal brief you filed with the Supreme Court. You wrote that "denying them the right to marriage serves only to demean them and their children, to degrade the dignity of their families and to deny them the full free and equal participation in American life to which every citizen is entitled." That's deeply emotional. It seemed to relay a deeply humanistic understanding of what it means to be gay, that feeling of otherness that is always and everywhere present in our lives. So I want you to speak about this case. I want you to speak to your decision a few years ago not to defend DOMA, and your decision now to go further and support what almost appears to be an expansion of the Equal Protection Clause.

Eric Holder: Let me first speak as a lawyer. It is the Obama administration's view that bans on same-sex marriage by the states are unconstitutional and they violate the Equal Protection Clause of our Constitution. I could go through all the legal reasons why that is so, but what underlies that is the notion that we are brothers and sisters, that we are all Americans. We have the same desires, we have the same fears, and we should be treated the same in the eyes of the law.

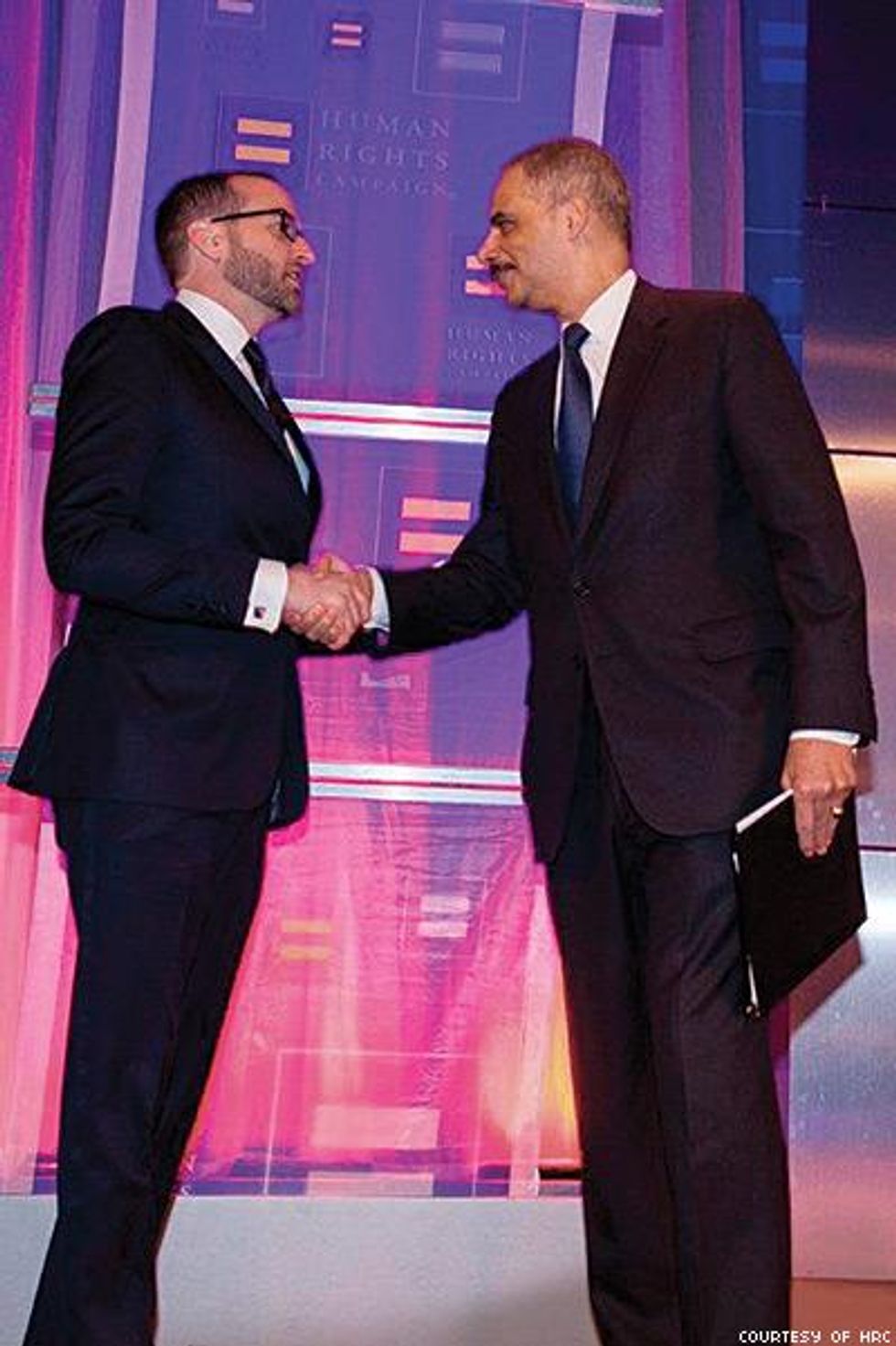

At right: Holder with HRC president Chad Griffin at the 2014 Gala

At right: Holder with HRC president Chad Griffin at the 2014 Gala

This is something the United States has evolved on. When I started as attorney general in 2009 there were only two states that recognized same-sex marriage. Now there are 37. The Supreme Court has an opportunity to make that the law of the land, and our friend of the court brief will say that, and say that these state bans are simply inconsistent with who we say we are as a nation.

We could continue to talk about this in terms of theory and the law, which is obviously important, but on a personal level this is about people. And it's about families.

I have a folder of pictures of DOJ employees -- members of DOJ Pride, our LGBT organization -- and it's pictures of their families, them having babies, on their way to their weddings, and celebrating their marriages. And in a fundamental way this is what this struggle is all about. It's about human beings, my fellow employees, my colleagues. It's about doing things that are consistent with who we say we are as a nation.

It's taken us to the 21st century to get to this point, but I'm proud of where we are as an administration. I'm proud of where I am as attorney General of the United States. And I'm proud of where I am as an African-American man.

I think it's wonderfully surprising -- if not slightly ironic -- that the greatest political proponents for equal rights for gay and lesbian Americans are two heterosexual African-American men, namely you and President Obama. The arc of the moral universe has bent significant in the past years. Can you tell me why this is important to you personally, not just professionally? Have you, prior to becoming attorney general, had some transformational moment of your own? Did you have family and friends who were gay before you came into this office?

Of course, I had family members and friends who are gay. Everybody would answer yes to that question if they answered the question truthfully. I had an uncle, Uncle Sonny, one of the best guys in my life. The first man I ever saw who drove a sports car, an MGB. It was the coolest thing in the world. He was near and dear to me and he was gay. We've all had people in our lives -- with a positive influence in our lives -- who are gay or lesbian. I was born in 1951. I experienced the civil rights movement. The movement that we're talking about today for same-sex marriage rights -- which is a part of the larger gay and lesbian fight for equality -- that is the civil rights struggle for our time. This is the fight to make real the promise of America for all Americans, regardless of their sexual orientation.

Above: President Obama and Holder in prayer as they attend the National Peace Officers Memorial Service at the U.S. Capitol on May 15, 2013.

Above: President Obama and Holder in prayer as they attend the National Peace Officers Memorial Service at the U.S. Capitol on May 15, 2013.

It seems that at the heart of the American experiment, there has always been a fractured understanding of whom the phrase "We, the people" actually includes. Do you see the gay rights movement as being distinct from the civil rights movement?

I see it as a logical extension of the civil rights movement, but I wouldn't restrict it to the civil rights movement of the 20th century. "We, the people" did not include women originally. It did not include African Americans. And it certainly did not include, in the fullest sense, gays and lesbians. So there has been a progression.

I think as attorney general, it is incumbent upon me to use the power that I have in this office, especially in the service to a president who shares my worldview, to expand that notion of who "We, the people" actually are.

One of the tactics of the conservative right has been to invoke religious exemptions as a way of denying gay Americans equal protection and equal access. We've also seen this as a skillful tactic in the fight for women's contraceptive rights, most notably -- and recently -- in the Hobby Lobby Supreme Court case.From a legal perspective, does "religious freedom" present a challenge to federal protection of gay and lesbian Americans? If so, how? And how do you expect that this will play out in the coming years?

I can't predict what tactics might be used to try to counter the position that we are going to espouse, and what I hope the court will ultimately adopt, but there doesn't seem to me to be an inconsistency between a person expressing their strongly felt religious views and recognizing the humanity of somebody because of their sexual orientation. I don't see the tension there. Which isn't to say that there won't be some people who will try to use a religious reason for not recognizing what I hope the court will say in making an equal-protection finding -- but we'll deal with that. If not me as attorney general, my successor or her successor will deal with that.

The nation is in a fundamentally different place than it was 20 years. The nation is in a fundamentally different place than it was even six years ago. There has been an evolution. As I talk to my children about same-sex marriage, about gay rights, they don't understand what the controversy is, why this is a big deal. They've been raised in a fundamentally different way. My kids were born in the mid-to-late '90s, and I think the country has evolved and I think that next generation, my children's generation, they will look back on all that's going on now and wonder what was that all about? What was the controversy all about?

Above: President Obama and Holder speak on the situation in Ferguson, MO., in the White House.When President Obama officially came out in support of same-sex marriage, he referenced Sasha and Malia. He referenced the fact that they had friends who were being raised by gay parents and how, in their minds, it wasn't odd. And that is a part of what helped him to evolve. I understand that from a political perspective, when he was running for office, he couldn't be fully supportive. Did you also have a political evolution and not just a personal one? Did you always believe that gays had the right to things like marriage and adoption? Or was that something that over the course of time, you came to see as being fundamentally the right thing to do?

Above: President Obama and Holder speak on the situation in Ferguson, MO., in the White House.When President Obama officially came out in support of same-sex marriage, he referenced Sasha and Malia. He referenced the fact that they had friends who were being raised by gay parents and how, in their minds, it wasn't odd. And that is a part of what helped him to evolve. I understand that from a political perspective, when he was running for office, he couldn't be fully supportive. Did you also have a political evolution and not just a personal one? Did you always believe that gays had the right to things like marriage and adoption? Or was that something that over the course of time, you came to see as being fundamentally the right thing to do?No. I have evolved as well. I was a young judge here in Washington, D.C., when a case was brought by a same-sex couple seeking to be married. And a judge wrote what I thought was a very thoughtful opinion, denying that right. I remember reading that opinion and thinking it was legally appropriate, and thinking, "I guess I agree with that." But what struck me about that was that it wasn't clear, necessarily, to me. I think back now to that young judge, to that opinion, and I'm in a fundamentally different place than I was then. This would have been the late '80s or so. People are educated. We evolve. We get better.

Things get better.

I hope that I've gotten better.

What do you see on the horizon for transgender equality? We've had greater visibility for transgender Americans, but they continue to face high levels of violence and discrimination. Much of that discrimination and violence is directed at trans women of color. Has the administration considered specific action to address the needs of trans people?

We issued regulations in December of last year that references the Civil Rights Act -- to say that discrimination against transgender people is illegal, inappropriate, and inconsistent with the Civil Rights Act. Beyond that, we have been very forceful in our enforcement of the Hate Crimes Act, so that people could not be attacked because of who they are or how they appear to be.

It took a long time in getting that expansion of the Hate Crime statute, and it is something that I think is a proud achievement of this administration.

I know you said you can't predict the future, but I'm looking at what happened with respect to the Voting Rights Act and it bothers me that we're making so much progress and yet when generations pass, many people don't see why it was even necessary that particular progress needed to happen. With respect to what the administration is doing in support of marriage equality, there is no codified law like the Voting Rights Act. What do you see as being necessary to solidify the rights of gay people? Do we need the equivalent of a 13th Amendment or 14th Amendment?

I'm not so sure. I think it really comes from a shift in attitudes, a shift in sensitivities. We have to remember in 1967 when interracial marriage was prohibited, that was a big deal. We look back now and think, "How could we possibly ban marriage between an African American and a white person? How could that be something you would even think about doing?" I think we will see a similar progression here when it comes to same-sex marriage. And I want to keep emphasizing that same-sex marriage is extremely important: It has impacts on people's financial lives. It has impacts on health care, impacts on child rearing -- a whole range of things. But it's only one part of the larger struggle for the recognition of Americans as Americans regardless of their sexual orientation.

I think the nation is ready for that. Once the nation has moved in that direction, once my kids are adults having their own kids, I'm confident that we, as a nation, will not only evolve, we will stay in the place to which we have evolved.

Above: Eric Holder, Sharon Malone Holder, and Maya Holder shop at Bazaar Spices at Union Market November 2013 in Washington, D.C.

Above: Eric Holder, Sharon Malone Holder, and Maya Holder shop at Bazaar Spices at Union Market November 2013 in Washington, D.C.

A perception exists that African-American and Afro-Caribbean communities are more homophobic than the general population. But as you and President Obama have become trailblazers on this issue, have you witnessed a change in the black community on this issue? And what are the cultural and social factors that may contribute to a disparity in acceptance for African-American and Afro-Caribbean gays and lesbians?

I'm not sure why that has taken as long as it has. I don't think that we've made the same progress in the African-American community that I would have hoped. I still have friends who I talk to and who think that maybe I've gone a little further than they're comfortable with. So I'm not sure what it's going to take to get the African-American community as a whole to a place where I think we need to be.

But I think we have to be honest. There is still work that needs to be done there. And I frankly don't quite understand, given the experience that we had to deal with as African Americans -- being the other, having to deal with discriminatory laws, discriminatory practices directed at us. So it seems to me that there would be a natural affinity for people being supportive of the same things that we've fought so long and hard to eradicate. It seems to me that there is a need for a greater understanding, a greater unity, and greater struggle -- jointly. My hope will be that over time that will happen.

You've talked a lot about your children, you've shown me the photos of your employees with their families, and in your recent op-ed you juxtaposed gay Americans and children. I think the idea of gay people raising children, adopting children, and having children of their own would have been unthinkable to talk about so naturally before this administration. Why is that important to you?

Because I've seen it. I've seen it in the pictures I've shared with you of the great people in this Justice Department, the wonderful things they're doing with their kids. I saw it at the elementary schools where my kids went. I got to interact with same-sex couples who raised great kids...and raised not-so-great kids. They were just common, ordinary parents who were dealing with the same conditions that we were dealing with: kids who were dealing with their homework wonderfully and kids who didn't do their homework so wonderfully. But they were just people, just people trying to do right by their children. That is the thing that people have to understand.

It's a good thing that more gay people come out, because it is hard to demonize somebody that you know.

I can go back to Uncle Sonny, or other people who I grew up with who were gay, like a kid who was my age, Sammy. And I can think about those guys. I think of Sammy, who was a great ballplayer. He's a good guy. Uncle Sonny was the coolest guy I knew growing up. Rest in peace to my father, but Uncle Sonny was cooler. If you can have a person in your life, a gay person, and say this is a gay person to me and that person is cool to you, good to you -- it means that you view people of the same orientation in much the same way.

On the other hand, if gay people don't come out and the myths are allowed to exist -- the misperceptions, prejudices -- and not countered by real-world experiences -- then progress is hindered.

You talk about this cultural acceptance versus legal protections. Though we have the great privilege of living in a nation with an African-American president and an African-American attorney general, young men like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, and millions of boys like them, are targeted as criminals and dismissed as thugs. What should we glean from this? It seems we're in this amazing time in American history and yet so much prejudice and ignorance still prevail. Do you think that greater legal protection for gays will lead to better quality of life? Or do we need greater cultural acceptance? And if so, how is that achieved?

I think we have a moment in time. We have a moment in time where all the tragedies -- from Trayvon to Michael Brown to the Garner case in New York, and a case in Cleveland -- coupled with where we are dealing with this whole question of same-sex marriage--this is an opportunity. This is a real opportunity for this nation, on a couple of fronts, to make substantial progress. These kinds of chances happen every other, every third, fourth generation.

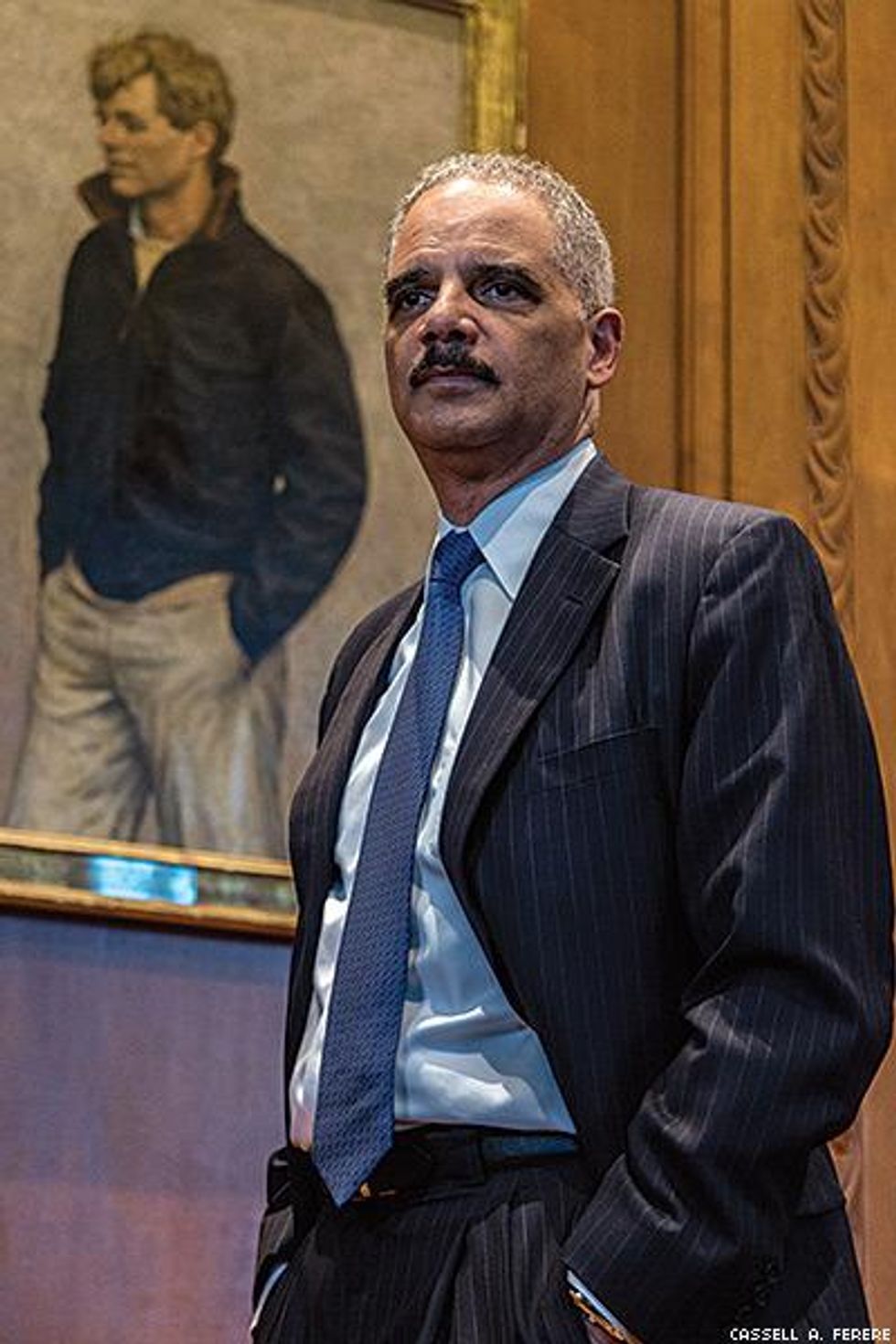

Left: Holder in front of Robert Kennedy portrait

Left: Holder in front of Robert Kennedy portrait

The nation dealt with a huge issue, and fought a civil war, and decided that slavery was a sin. The early part of the 20th century, we decided that women should get the right to vote. This is another one of those moments, it seems to me. And I think that those two struggles can be interwound; and if we do well in one, it will certainly help in the other. If we do well on both, it will help the nation.

You will vacate this office soon. How do you intend to remain the advocate for gay and lesbian Americans once you're out of office?

I hope that I will still have a voice that people will listen to and hopefully some will find persuasive. I took this job not to be a bureaucrat, not to simply move paper. There are four attorney generals' portraits in this conference room. The one over my shoulder...

Robert F. Kennedy?

Yes, Robert F. Kennedy, he is my idol, because he used his position as attorney general to make this country better, to make this country more perfect. He dealt with issues of his time, the civil rights movement. It was under his leadership that my sister-in-law [attended the integrated] University of Alabama when George Wallace stood in the schoolhouse door.

I've had the opportunity, as a result of serving under a great president, to deal with the issues of my time. And among those issues is the fight for same-sex equality, in all of its guises. Same-sex marriage is the issue that the Supreme Court will deal with soon, but the issues are larger than that.

My hope would be that fifty years from now -- as we are about 50 years removed from Robert Kennedy -- that people would say that Eric Holder struggled. He got it more right than he got it wrong, and that the nation was better as a result of his being attorney general.

This interview was conducted before the RFRA was signed into law in Indiana. The Supreme Court is expected to announce its decision on state marriage bans in June. At the time of this interview the U.S. Senate had not yet confirmed Holder's

successor.

Edward Wyckoff Williams (@WyckoffWilliams) is a television producer, correspondent, and columnist. He is a contributing editor at The Root and has appeared on MSNBC, CBS, ABC, CNN, Al Jazeera, ARISE, and national syndicated radio. In January 2015 his work was nominated for two GLAAD media awards.

Above: Holder with members of DOJ Pride

Above: Holder with members of DOJ Pride At right: Holder with HRC president Chad Griffin at the 2014 Gala

At right: Holder with HRC president Chad Griffin at the 2014 Gala Above: President Obama and Holder in prayer as they attend the National Peace Officers Memorial Service at the U.S. Capitol on May 15, 2013.

Above: President Obama and Holder in prayer as they attend the National Peace Officers Memorial Service at the U.S. Capitol on May 15, 2013. Above: President Obama and Holder speak on the situation in Ferguson, MO., in the White House.

Above: President Obama and Holder speak on the situation in Ferguson, MO., in the White House. Above: Eric Holder, Sharon Malone Holder, and Maya Holder shop at Bazaar Spices at Union Market November 2013 in Washington, D.C.

Above: Eric Holder, Sharon Malone Holder, and Maya Holder shop at Bazaar Spices at Union Market November 2013 in Washington, D.C. Left: Holder in front of Robert Kennedy portrait

Left: Holder in front of Robert Kennedy portrait