CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

I was never really a fan of whiskey. My father is, but then we are from Texas, and he also has a handlebar mustache and wears black snakeskin cowboy boots. The spirit has always been to me a good ol' boy's drink of choice, and as a gay man coming of age in Los Angeles, I was weaned on a strict vodka diet. Ever since Sarah Jessica Parker sparked the cosmo rage, whiskey never stood a chance.

Of course, I never really knew anything about whiskey, so with trepidation, I decided to accept an invite to learn all about it -- and I mean all -- on a five-day tour of the American Whiskey Trail. The journey would take me through the South but also to our nation's capital, and while I assumed a gay man in rural Kentucky would probably be a dangerous thing to be, l learned that whiskey is not only an American tradition but a spirit that bears a second look.

The oldest distillery in America is actually near Washington, D.C., at Mount Vernon, where George Washington himself distilled some of the finest whiskey for a then rum-soaked country. If you are really committed to the history of whiskey, then you must go all the way to our nation's capital to see the still-functional distillery and hear the history as told to you by men in period dress or peruse the small but informative museum. Mount Vernon is currently applying for a license to offer samples of whiskey on site, so for now you won't get to taste any of the handful of batches it has put out. But the heart of whiskey country is definitely the South, so after my stopover in D.C., I boarded a plane for Nashville.

The American Whiskey Trail can be viewed as a sort of wine-tasting of the South. Tourists come to Nashville, from which nearly a dozen distilleries are with in two hours' driving distance. After arriving in Tennessee, I headed an hour outside out of Nashville to Normandy, a small town nestled in the rolling hills of the countryside and the home of the George Dickel distillery. Any trepidation I had about leaving the safe confines of urban Nashville was calmed by the beautiful meadows and lakes lining the highway -- that is until we broke off from the main road to a smaller, winding country road to seemingly nowhere and I saw a KKK flag flying proudly.

Dickel is very small distillery founded in 1870, and it has a sort of homespun vibe. The sweet master distiller, who is missing a few, greeted us and walked us through my first fully operational plant. It was at this point I started to truly grasp what whiskey even is. All whiskey is made from a ratio of corn to rye to malt barley that is fermented and then distilled -- boiled basically, until the alcohol steam comes off and is captured. What distinguishes Tennessee whiskey, I learned, is something called charcoal mellowing. I remember the slogan from bottles of Jack Daniel's on drunken nights in high school, but I always thought of it as a gimmick, like saying Lemon Pledge, now with new pine scent. Turns out this little addition, which involves letting the whiskey trickle through layers of charcoal, not only drastically affects the flavor but is also a laborious accomplishment. To make Dickel's charcoal, for instance, the distillery uses sugar maple harvested in winter when the sap is lower, and it is then burned. But every brand has its own special technique.

As for the whiskey, the ingredients are first mixed in giant mash tubs two stories high. The concoction looks like an enormous bowl of creamed corn and is bubbling, not from a heat source, but from the enzymes in the barley actually breaking down the starches in the corn and rye. One of my guides told me to lean over and take a big whiff of it. When I did -- and then nearly fell down and threw up -- he laughed uncontrollably. "It's like smelling a thousand corn farts," he said of the fact that I had basically ingested a massive nose full of CO2 coming up from the fermentation. I was told I had now been initiated into whiskey culture, which made me feel good, as we were still in the heart of what I assumed to be a territory hostile to gays.

After our tour and delicious lunch of baked beans, salmon, and and indescribably good brownie-bottom pie, served by a sweet Southern woman with a thick accent, we sat down to sample Dickel's concoctions. These delightful Southern meals can be arranged at nearly every distillery you visit if you are traveling in a group but harder to come by if you are flying solo.

The other thing I learned that makes whiskey is the aging process. Whiskey is aged in charred white oak barrels. The charring adds a flavor as the whiskey expands and contracts from winter to summer, soaking up the flavors of the wood. The South, it seems, makes such distinctive whiskey because it has drastic temperature changes, from incredibly hot summers to very cold and sometimes snowy winters.

We tried various years of aging from three to 12 -- the flavors get sweeter as they get older. But the whiskey had yet to win me over. Then the master distiller, whose job it is to stay on top of the batches, sample them, and get the flavors just right, served up a 13-year-old straight from the barrel. Another requirement for American whiskey is that it needs to be distilled down to no more than 40% alcohol by volume (80 proof), but this renegade he served is 115 proof. The caramel-colored concoction roped me in.

"This is the one for me," I declared to my companions, all spirits writers who seem uninterested in the fact that until now I had not actually had a whiskey I liked. Now, with a little buzz going, I boarded the bus for our next stop.

Next we headed to the Woodford Reserve distillery in in Versailles, Ky., which makes a superpremium bourbon. The spirit gets its name from the French Bourbon region of Louisiana, though it is no longer made there. The Woodford grounds look like a Scottish plantation, and the bourbon is aged in stone warehouses that provide their own distinctions when it comes to flavoring the alcohol. Woodford is very smooth, with a hint of mint, and has a caramel finish.

There are dozens of distilleries not far outside Nashville, not all of them equipped for visitors, but you will want to spend more than half your time there. The only downside is that most are about two hours away from the city and about two hours away from each other. There are a number of small-town bed-and-breakfasts near each, but I am not sure I would feel comfortable staying outside the city.

For accommodations, Indigo Hotel Nashville West End (1719 West End Ave., 615-329-4200) is a swanky spot that might just fit the bill. Located near Church Street in the heart of Nashville's gay district, it makes going out at night a breeze.

For a more upscale and quieter time, stay at the historic Hermitage Hotel (231 Sixth Ave., 615-244-3121). This grand hotel has been around since 1910 and was visited over the years by celebrities from Greta Garbo to John F. Kennedy Jr.

As the week carried on, I quickly learned that once you have seen one distillery, you have pretty much seen them all. They all consist of a tour of the distilling machinery and end in a tasting of some the company's selection. Master distillers talk to you about flavor and color and hints of cinnamon achieved from their very specific process. But some of the distilleries have actually erected tourist attractions to make the experience more exciting.

Jack Daniel's, for instance, is the Disneyland of distilleries. People from far and wide make a pilgrimage there to worship their favorite brand, and you quickly realize that Jack Daniel's is more than alcohol, it's a way of life. A giant museum kicks off a tour that takes you through the grounds and to the original shed where Mr. Daniel kept his office, where your overall-wearing guide regales you with stories.

Maker's Mark in Kentucky is by far the most fun and interactive. The visitors' center is a quaint little house painted the brand's signature red and features computerized talking paintings of the founding family telling the history of the brand to each other from facing walls in the study. The kitchen is superkitsch and done up to resemble the original 1950s kitchen where the Samuels family first invented their bourbon. Grab a fresh-baked cookie and some lemonade as your guide tells you how Mrs. Samuels first decided to dip the bottles in hot wax to make the now-famous seal. After viewing the factory floor where they still hand-dip every bottle, you get a chance to dip your own bottle in the enormous modern gift shop.

Kentucky is also the home of Jim Beam, by far the largest distributor of whiskey. Though it has a number of great brands to sample, unfortunately it is in the process of upgrading its visitors' center, and right now it is just a gift shop sitting so close to the sewage treatment plant that the whole place smells terrible. This would be a destination for the true connoisseur who was willing to brave all for the chance to sample.

In Kentucky, I recommend staying in Louisville and driving out to the distilleries by day. Louisville was the trip's biggest surprise, actually, particularly the 21C Museum Hotel (700 W. Main St., 502-217-6300) which is a must-visit. Entering the lobby to check in, I was greeted by an enormous painting by Kehinde Wiley, the gayest thing I had seen on my journey so far. Nestled in Louisville's thriving arts district, 21C is as much museum as hotel, and its 9,000 square feet of exhibition space, featuring a permanent collection as well as ever-changing installations, is open to the public 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The hotel is also a part of the Urban Bourbon Trail, which involves nine establishments around the city. Just go to a participating location and ask for a "passport" and you can do your own sampling tour of the local brands in an urban pub crawl.

The American Whiskey Trail is definitely a commitment and for the true whiskey lover, but you will find friendly people and a welcoming atmosphere as you sample some of the best whiskey in the world. I ended the trip with a whole new attitude about the South and my preconceptions. While I don't think things are 100% there yet when it comes to politics and the gay community, it is not as bad as I thought either. Besides, after a few whiskey sours, everyone is your friend.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

Brittney Griner and her wife Cherelle are expecting! Here's when baby Griner is arriving

April 15 2024 12:52 PM

Tennessee Senate passes bill making 'recruiting' for trans youth care a felony

April 14 2024 11:17 AM

Italy’s prime minister says surrogacy ‘inhuman’ as party backs steeper penalties

April 14 2024 10:36 AM

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

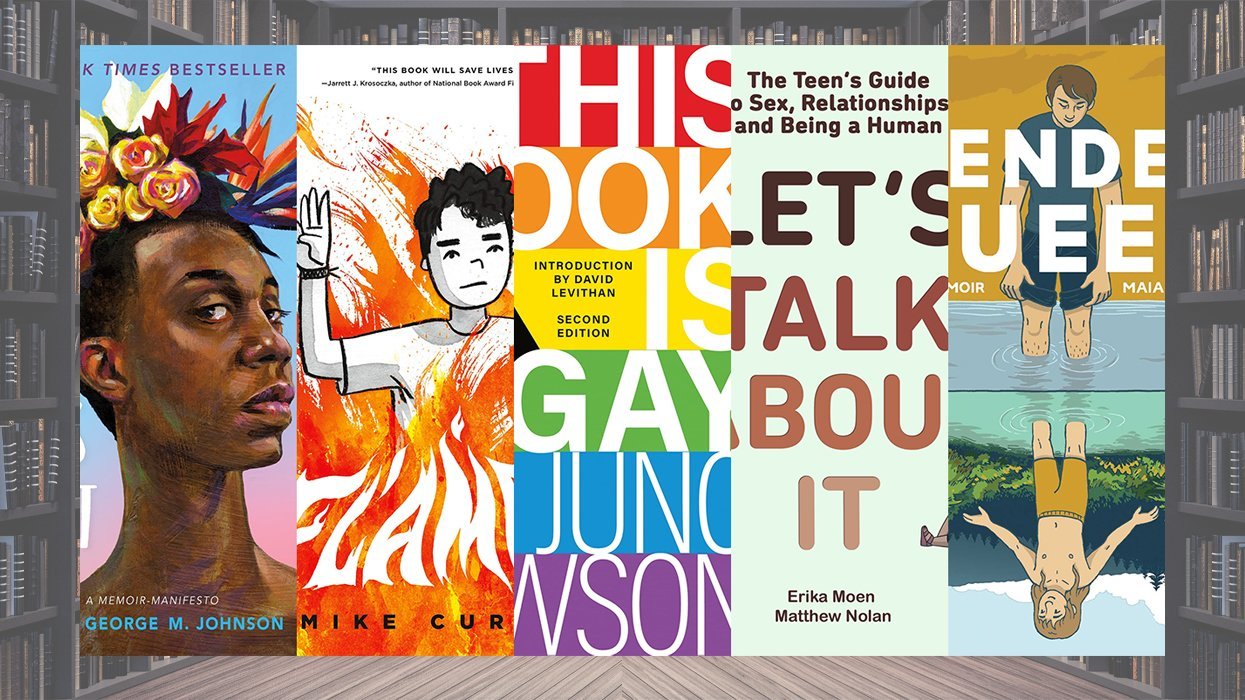

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM