This story is not a new one -- which is ironically what makes it more poignant.

Unquestionably, it is not easy to see a friend in a coma because he tried to hang himself. This is particularly evident when the friend was affable, beautiful, charismatic, driven. When his present situation is attached to drugs, the situation becomes even more complex and less discernible.

We have a party issue, and it is something we need to address.

I have always come from a philosophical camp that I think many men come from: You are an adult with your own brain, so live as you choose to live. Even when it came to drugs, I applied this belief; even when it came to him, I applied this belief; even when he came out of rehab and sought to "hit the slopes in L.A.," I applied this belief. His choices are ultimately his choices and while I can offer my two cents, I can't fit his bill.

Though a tinge of guilt continues to pervade me -- I was raised Catholic, after all -- I know I am not at fault. No one is ever at fault in such situations. However, far more disturbing than the slippery slope of guilt, I've been told that I should be angry. Angry at him for making this choice, for permitting drugs to invade his brain on such a level, for hurting the people involved in his life, for dragging them through the strange space that is a coma.

Angry?

I am not angry. I'll never be angry about something like that. I am downright sad, people. Flat out, no-questions-asked sad.

The simple fact is that he was someone I deeply cared for. He was someone who gave me his student ID so I could ride transit for free. He was someone who would show up with a bottle of wine and a plethora of groceries as a thankful gesture for letting him stay at my house. And that someone was in such a dark space -- drug-induced or otherwise -- that he not only wanted to try and end his beautifully disastrous streak of excessiveness, but he wanted people to know his pain by hanging himself.

There is a very specific sense of gravity in that form of suicide: the painful, slow extraction of air from your body is as masochistic as it comes since there is not only a moribund physical pain, but the elongated minutes one must experience -- and can't go back on -- once they let the weight of their body do the work. Those minutes -- something I truly cannot imagine since it is so removed from the spectrum of common experience -- is the writing of one's farewell letter. Then comes the metaphorical signature that is the final act: the body itself, a lifeless landscape of one's last words that never made it to a pen and paper.

As I said, this story is not a new one. But the pervasiveness of partying that we as a community, and as a culture, have embraced cannot continue on the level it is working on.

The reality of the world of drugs is like the reality of all addictive things in the world: there are some who can handle it every now and then, having some natural control sensor that permits them to stop when needed, and there are many who can't. There are those who use a drug in a time of struggle and then move on; there are those who use them in a time of struggle and never lift themselves out. This isn't a matter of character or personal strength; it's little more than how one's neurons fire off. This is why, despite my friend's overwhelming success in television and a supportive family and partner and privilege, he still slipped down the hill like someone who faced far more dire struggles in life.

My aforementioned philosophy might be logically sound but it is not ethically coherent. "His choices are his choices," in this situation, echoes hollow. The philosophy even reflects a certain type of cowardliness that, perhaps, I am just unable to admit that I was too chicken-shit to engage a confrontation when he pulled out his baggie shortly after rehab; that the excuses in my head -- I hadn't seen him in months, this will be fun, it will send a signal to him that I'm not here to judge him -- were just that: excuses.

What I propose is something that is not easy because we have to step away from ourselves in order to achieve it. It requires continual acts of selflessness by putting your own needs aside when someone else can't handle. It requires not pulling out your sack of cocaine in their presence. It requires forcing mundane rounds on the couch in front of a TV and just doing that all-too-old-school thing known as talking. It requires an active approach that puts aside your capability to handle partying in favor of their inability to stop when they need to. It requires vulnerability, a slight loss of control, a giving in -- and maybe even a little anger from their end. It requires us to face the reality rather than waiting until a moment when a life is no longer a life.

It requires us to grow the fuck up.

BRIAN ADDISON is an associate editor for the Long Beach Post and a senior writer for Los Angeles Streets. Follow him on Tumblr.

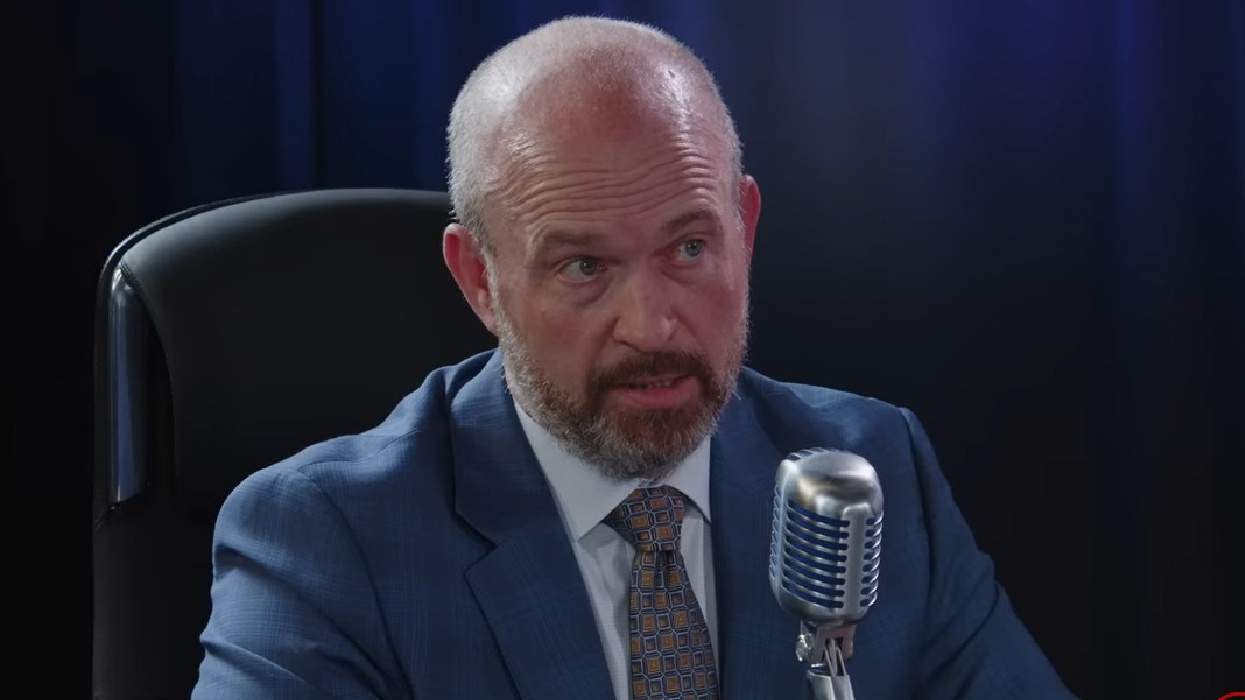

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.