A new study indicating that antiretroviral medication is effective in preventing HIV may be raising as many questions as it has answered.

Among them: Who will pay for it? Who should take it? And will it lead to less condom use among gay men?

"It's an incredible biologic success with incredible behavior challenges," Mitchell Warren, executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, said of the study, published Tuesday in The New England Journal of Medicine.

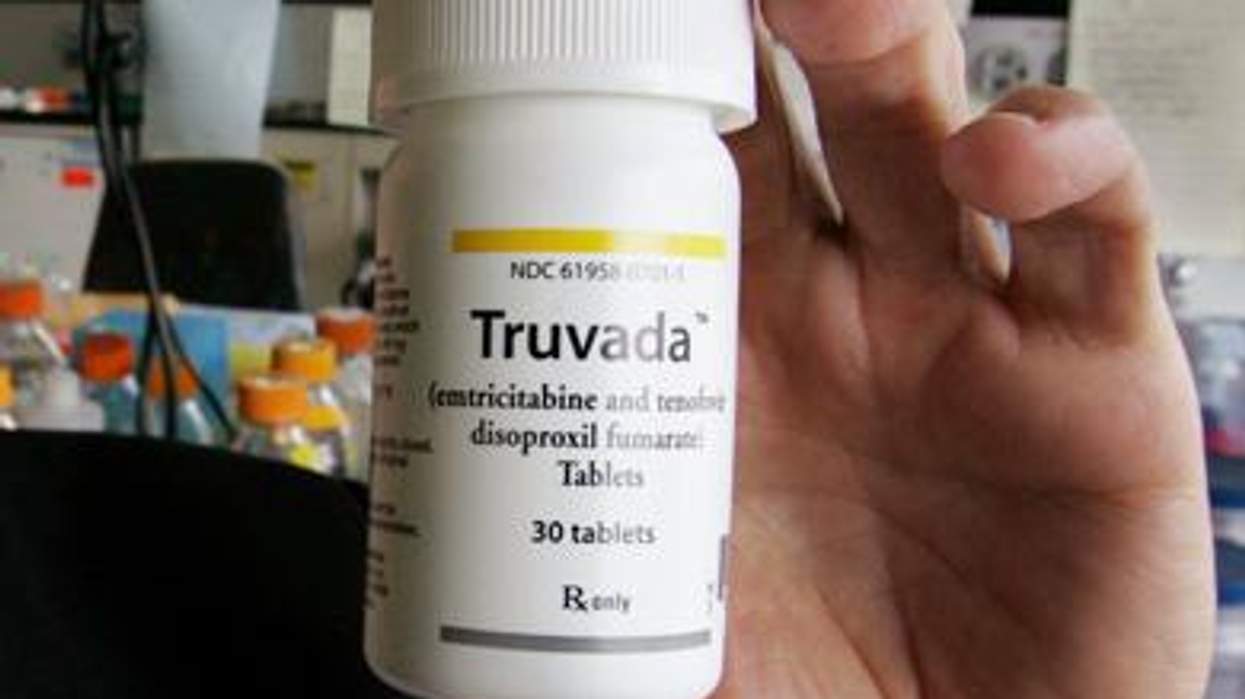

Funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and involving nearly 2,500 gay men -- as well as transgender women who have sex with men -- the three-year study found that those who were given the antiretroviral pill Truvada were 44% less likely to become infected with HIV than those who received a placebo.

When participants took the medication as directed 90% of the time -- verified through blood tests --Truvada was 73% effective in preventing infection. All study subjects received HIV testing and safer-sex counseling every four weeks.

Though "pre-exposure prophylaxis," or PrEP, is not new, the study is the first large-scale look at a prevention method that is expensive and unavailable to many.

White House officials quickly praised the study results as encouraging, though hardly a replacement for established methods of HIV prevention, including proper condom use. In a statement to The Advocate, Jeffrey S. Crowley, director of the White House Office of National AIDS Policy, said that further research on PrEP must include women and other groups.

"ONAP recognizes that one study is not definitive and this single study was focused on one population," Crowley said.

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. Agency for International Development "have been active participants in a global effort to examine this issue in different populations and answer other critical questions in order for us to know how to use these findings as part of a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to HIV prevention," Crowley added.

Implementing PrEP as an effective HIV prevention tool presents many challenges. Getting at-risk individuals to take medication consistently is one of them: Truvada can initially cause minor side effects such as nausea, while long-term health complications resulting from the toxicity of antiretroviral drugs remain a concern.

"This data is exciting, but it only begins to tell a story. We don't know how to sustain PrEP as a regimen," AVAC's Warren said. "It's not unlike the situation with condoms. They're effective when people use them correctly and consistently. This pill doesn't change that."

It's also unclear what dosage is most effective -- and practical for general use. "We may find that we don't need daily use," said Cornelius Baker, a senior HIV/AIDS adviser at the AED Center on AIDS and Community Health and a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS. "Maybe there are strategies for intermittent use. Even people who were 50% adherent [in the study] were still seeing a benefit. ... We still need to know what the real-world implications are."

Other experts said that PrEP treatment is simply not a viable option for most people in the near term, with funding for HIV/AIDS care and outreach in the U.S. facing continued setbacks.

"It's not available from a very practical perspective," AIDS Project Los Angeles executive director Craig E. Thompson said of PrEP, though he lauded the study and its potential implications for further research and future prevention efforts. "If you're a gay man who's not infected, I don't know where you would go to get these drugs. There's not an agency in the country that subsidizes it. Is insurance going to pay for an HIV-negative person's medication?"

PrEP may be most effectively implemented in communities with higher risk of infection and lower rates of condom use, Thompson said, including sex workers, who are often paid more money for engaging in unprotected sex.

And although the drugs that make up Truvada are less likely than some other meds to cause a drug-resistant strain of HIV to develop, some wonder about the risk that a person who contracts HIV while taking the medication as PrEP can transmit a Truvada-resistant strain to a sexual partner.

"Would I recommend someone [use PrEP]? It's a personal decision," said Robert Gallo, director of the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. "If you're taking the drug, and you're [healthy] now, you don't know the long-term effects. You don't know if you're going to create a drug-resistant variant."

As far as who might pay for the medication -- insurance companies, drug companies, government agencies -- Baker said it's too early to speculate, though HIV prevention likely remains less costly than treating those already infected with the virus.