CONTACTAbout UsCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

We need your help

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

Your support makes The Advocate's original LGBTQ+ reporting possible. Become a member today to help us continue this work.

"Hello, this is George, " said the voice on the phone. "George Michael." The twice-repeated first name, easy familiarity, and British accent reminded me of another iconic greeting ("Bond. James Bond") Surely, I must be dreaming about this George. George Michael. Then again, this "George Michael" voice triggered memories: "Freedom," "I Want Your Sex," and "Club Tropical." For a closeted 16-year old driving around in his red Karmann Ghia and loudly singing off-key, George's songs promised something unspoken, urbane, and sexy.

Still dreaming, I listened to "George Michael" describe reading my article "Hiding Out" in Attitude, a U.K. glossy. I got out of bed and looked outside. It was dark. I wasn't dreaming. George Michael really was telling me, "I was very moved by the story. I want to make a video." Could I hook him up with the kids who'd escaped from gay-to-straight "hospitals" into an underground network of safe houses?

"No," I said, taking notes. There were two weeks to find the safe house kids, edit their interviews, and deliver the video ("Freedom, Part 2"?) to RFK Stadium for George's performance at Equality Rocks. "But I can."

Problematically, while I knew exactly what I would do for the video, I had no clue about how to actually make a video. No worries -- I'm from L.A.; I faked it and George signed on, pop star style, agreeing to pay for everything. His manager, Andy Stephens (now overseeing American Idol winner Susan Boyle), made one thing clear: George Michael Pop Star was paying for this project out of pocket -- his pocket. And though those were deep pockets, George Michael the person wasn't a spendthrift. I had to make every penny count.

Ninety minutes later, I was dispatched to San Francisco. I done this before -- traveled north in search of kids, underground and safe houses. But this time I couldn't help but wonder, who was I looking for --the kids or me?

When I was a teenager, I'd run away to San Francisco and "life." I liked the "idea" of the Bay Area and its history of social activism. I was eager to become a vegan and ... take modern dance classes! Though I was now an adult who, on occasion, ate meat and had somewhat more defined goals, returning to the Emerald City still made me nervous. I had four days to make a video based an article that took me two years to write. I was, however, sustained by some weird belief that the safe house had once again "chosen" me to tell its story.

I wasn't completely alone in my quest. John Keitel, a USC film graduate, and I drove to S.F and checked into Beck's Motor Lodge, a shabby-tawdry-cheap-chic tweaker destination. Crucially, Beck's was centrally located, near the Tenderloin.

That night we drove to Polk, where commerce thrived 24/7, all of it human: sex and drugs. Same as the local predators, we circled blocks, on the hunt. The kids ran away from us, darting around corners and hiding in dark alleys.

"Pull over," I said. Across the street, I saw kids getting high. John parked. We discussed approaching "them." The group was clustered in a parking structure lit by nauseating citrus-yellow lights. "No," I said. "Let's not." Driving away, I knew we'd just passed on a great opportunity. One of those kids must have contact with a safe house. But I'd become afraid and told myself, It's too dangerous.

We returned to Beck's without footage. I lay down on the lumpy mattress and looked left, at the digital clock. The red numbers flipped. I started counting: three days to tape, four to edit, hours to fly and deliver. Already we were out of time. In the other bed, John ate chips and watched TV. I looked at the camera. It sat in the chair, stubborn, glum and dead. Before, all I needed was paper, pen, and pluck. Now I was at the mercy of a cyclops. I rolled off the polyester bedspread and picked up the lens cap, ready to screw.

A knock on the door. I paused. A shadow was outlined on the curtain. John and I exchanged glances. We hadn't ordered room service -- there wasn't room service at Beck's. "I'll deal with it," I said, prepared to shoo away one of the roving zombie tweakers, and opened the door. "Listen ... " A boy stood in the breezeway, his face hidden in the shadows. A duffel bag was slung over his left shoulder.He smiled, shy. "Hi," Chad Brian said, in a heavily adenoidal voice. Miraculously, our first subject had flown from Florida and delivered himself to our room. Now, I thought, taking his bag and ushering him into the room, we begin.

The next day, we drove to the Tenderloin and ditched the car. Chad Brian's presence jolted me into the realization that the safe house documentary couldn't be made at a remove. More so, "Hiding Out" demanded me to reinvest myself in a topic I was pained to revisit.

We were walking down Polk Street when I looked away and down a cross street. I saw a girl walking away, skateboard hooked under right hand. Something made me shout, "Excuse me!" She ignored me. "Deeth!" Chad Brian yelled. She turned and looked. The clock was still ticking, but we now had our second interview. Marci (who'd run safe houses) and National Center for Lesbian Rights attorney Shannon Minter followed.

The days blurred. We left the roachy motel, returned to L.A. and edited "Hiding Out." John left the post-production house, video in hand, late for his flight to D.C. I was done. Or was I? For the second time, "Hiding Out" left me with a sense of accomplishment but not completion.

Chad Brian's unlikely yet perfectly timed appearance at Beck's was our project's desperately needed turning point. He was the catalyst for "Hiding Out." I saw myself reflected in Chad Brian. Like me, he'd been ground up by the psychiatric industry's voracious appetite for money and gay teenagers. Like me, Chad Brian was forever searching to redeem himself from his horrific experience. And, like me, Chad Brian was a brave young gay person who carried on despite having every reason in the world to curl up and die.

Chad Brian's presence reminded me why I was here in San Francisco. "Hiding Out" wasn't about a pop star or money. Nor was "Hiding Out" (and, later, Hidden) about "issues" -- safe houses, runaway youth, reparative therapy. "Hiding Out" -- and now Hidden -- was always about survival and survivors. I'd always kept my distance from the kids, convincing myself it had something to do with "impartiality." Yet on some level I knew from whence those detached feelings sprang -- I just couldn't deal with their source. Namely, all my buried feelings of shame and self-loathing that were triggered every time I dealt with the kids. They were, in essence, reminders of the passage of time and the unacknowledged reality that certain facts of my life were immutable, and still very much alive.

As time passed and I disengaged from the safe house story, another question emerged: Would I ever truly be free of the persistent feeling that I'd failed? Because I was dogged by the feeling that, despite all my best efforts and good intentions, I'd failed the kids. Because, really, nothing had changed. I'd spent a chunk of my life on something for results that were at best indefinable.

Curiously, it was only when I turned away from nonfiction and wrote (the fictional) Hidden that I was finally able to face the truth. A truth that had nothing to do with the safe house story's failure to change laws or the underwhelming response of the LGBT "community." Often I blamed the (adult) LGBT community, who either couldn't deal with its own deeply buried pain (everyone who's gay was a gay youth). Or, in my then still young mind, turned me into an observer of "adult" issues braided with pleasure and death (the AIDS epidemic was then in full swing.)

Years later, when I opened my first copy of Hidden, I read the first lines-- "I am high" --and was finally able to see the truth of what I'd been searching for all those years. Safe / House -- or, like everyone from Odysseus to Dorothy, safety and home. For me, the safe house story had been my personal search for redemption -- ultimately, not for "the kids," but my own still broken teenage self.

For more information on Mournian, click here.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Bizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

November 14 2025 4:08 PM

True

Jeffrey Epstein’s brother says the ‘Bubba’ mentioned in Trump oral sex email is not Bill Clinton

November 16 2025 9:15 AM

True

Watch Now: Pride Today

Latest Stories

Joe Biden to receive top honor at LGBTQ+ leadership conference for his contributions to equality

December 02 2025 6:00 AM

On World AIDS Day, thinking of progress and how to build on it in the face of hostility

December 01 2025 7:47 PM

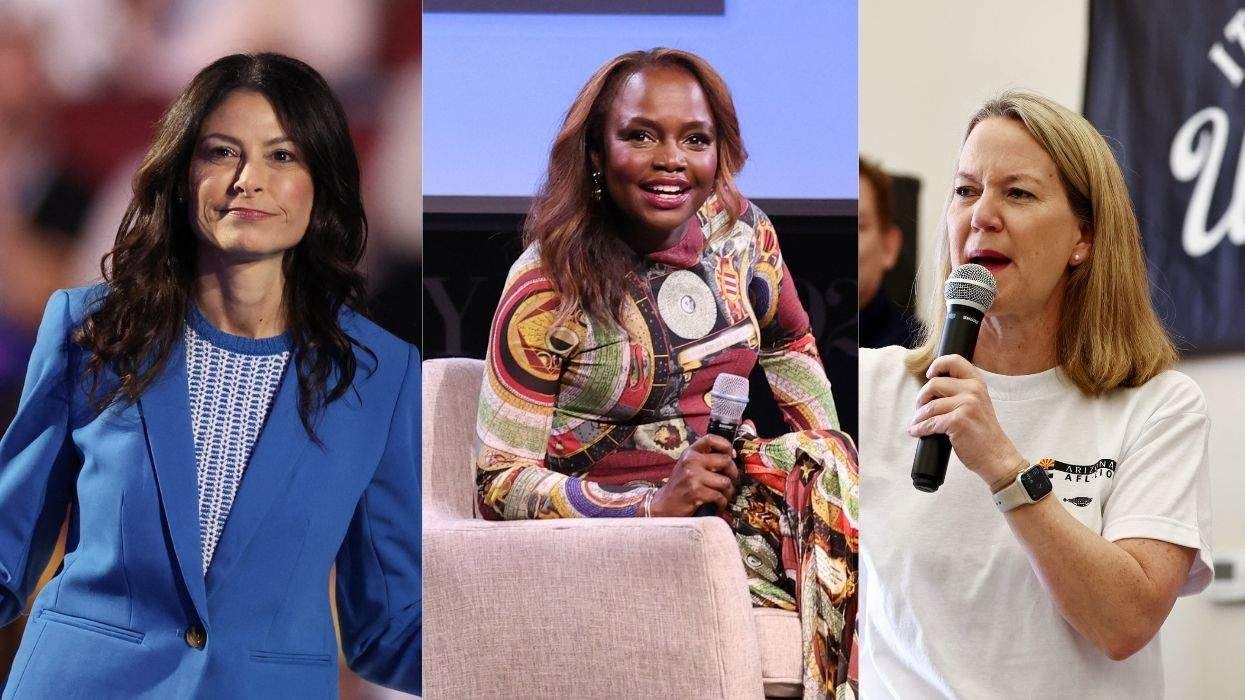

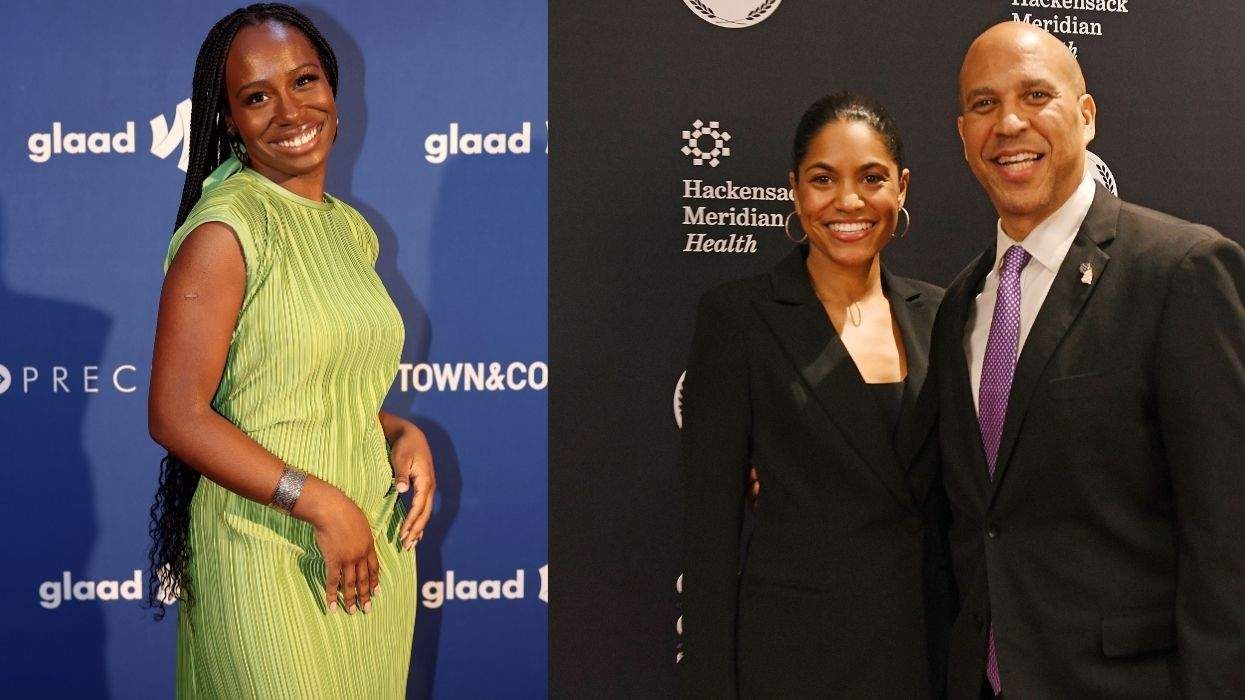

Ex-Biden White House aide called out for implying Cory Booker’s new marriage is suspicious

December 01 2025 6:04 PM

True

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border (in photos)

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

Maryland community outraged after ‘bigoted’ early morning rainbow crosswalk removal

December 01 2025 11:07 AM

19 LGBTQ+ movies & TV shows coming in December 2025 & where to watch them

December 01 2025 9:00 AM

Gay NYC councilman running for Congress says America is at a crossroads

December 01 2025 6:52 AM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes