In May 2012 I attended a celebration recognizing IDAHOT, the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia, on a hilltop outside Kampala, Uganda. I was the sole westerner present.

The celebration came at a time of heightened security threats and uncertainty about the passage of Uganda's infamous Anti-Homosexuality Act. Rumors and emotions were high, but so was hope -- and appreciation. Although I didn't know what to expect, I wanted to support my friends in Uganda's beleaguered and brave LGBTI activist community. I knew from experience that these friends, much like exchanges with other Ugandans and East Africans, presented a gateway to better understanding myself and the world.

Pepe Julian Onziema, programs director and acting advocacy officer for Sexual Minorities Uganda and the event's emcee, warmly welcomed his guests and shared a few "house-keeping" basics: "Media will be present, make it known if you do not want to be photographed," "Do not draw attention to yourself when you leave here today," "Banange [or, my dears], please keep time," and the like.

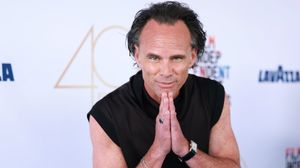

Afterward, Onziema invited guests to come before the community to tell their story. One of the first to rise and take the microphone was Cleo Kambugu (pictured above), a trans woman activist I hadn't met.

Cleo told a story unlike any I had ever heard. But this is because I was largely ignorant. Even though I am a gay American, I'd not met a transgender person and I was almost completely clueless about transgender issues, which I now understand meant that I did not know much about gender and sexuality -- not even my own. To be completely honest, I wasn't certain I wanted to know; it seemed messy. Gender and sexuality unboxed and shown for what it really is? In this I perceived (that is, projected) a subtle threat.

But I was instantly intrigued by Cleo. Her personable demeanor and unassuming wit put me at ease and invited a closer look. Her story, concentrated into a 15-minute retelling, blew apart my assumptions with incredible precision. I mean that she cut to the heart of the matter -- of which we all are made -- and she did not shy away.

I have never forgotten how she calmly stood before her peers and told her story. In a room full of Ugandans who aren't naturally prone to rapt silence, no one uttered a sound the entire time she spoke. Thus began my education on what it means to be transgender and how gender is much more complex (and varied, and beautiful) than its conventionally conceived opposites.

Over the many months that followed, I got to know Cleo and other members of the Ugandan LGBTI community very well. They took me in as one of their own. Eventually several of us collaborated on a photo and storytelling project with our editor, Sunnivie Brydum, who helped steer the project to its completion. Our photo essay was published in The Advocate magazine and on Advocate.com in early 2014. Cleo's portrait and essay was the lead story in the online version, and was followed by the stories and photographs of 11 of her peers. The project went on to be honored by GLAAD and the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association in 2014.

See Cleo's portrait and read her story from that award-winning series on the following page.

Unfortunately, and perhaps more notably, our photo essay was reprinted in its entirety without permission in Uganda's Red Pepper, on February 28, 2014, just days after the country's controversial bill passed into law. Cleo's face and those of her colleagues appeared on the front page of Uganda's leading tabloid, under the headline "Uganda's Top Gays Speak: How We Became Homos."

Our beautiful project, of which we were so proud and on which we had worked so tirelessly, had been stolen from us and marred. To this day we have not received justice for this theft. A lawsuit in Uganda against the owner of the Red Pepper would have brought attorney fees and court costs, which we couldn't afford without any certainty about the outcome, or without an LGBTI donor or organization footing the bill. And it is almost guaranteed we will never receive a sincere apology from the tabloid editors who sold their paper at our expense -- and especially at the expense of the safety of these brave Ugandans.

Many of the participants had to go into hiding or flee the country. Several of us had to give up jobs. Friends and families were torn apart. A few of my friends were attacked and beaten. All these terrible things happened to Cleo. She fled to neighboring Kenya.

Yet long before the bill passed and our photo essay was published and subsequently stolen, Cleo had already decided to claim her place in Ugandan society. She wrote an open letter to Uganda's Parliament. From her small dorm room at Makarere University, where she was enrolled as a graduate student in biotechnology, she began documenting and sharing her transition on YouTube. She would show Ugandans -- she would show all of us -- what it took to claim one's space in a society that did not want to acknowledge her.

Soon after, Cleo met Jonny von Wallstrom, a Swedish artist and filmmaker, and together they began working on a documentary called The Pearl of Africa. Through a series of several short episodes available for streaming online, viewers are granted an intimate look into Cleo's transition and its impact on her relationship with her boyfriend Nelson, and her family. Cleo, Nelson, and Jonny have been working on this film for over 18 months, and they still have much work to do.

I want you to take a few minutes and watch an episode or two of The Pearl of Africa, particularly the last one, released a few days ago. It's a beautiful introduction to Cleo. You can watch all six episodes on the last page of this article.

And then I would like you to help her. Within the next five days, Cleo must raise $3,500. If she does not, what she bravely set out to do in 2012 -- to fully transition and document her story for Ugandans, the global LGBTI community and future generations -- will be further delayed. You can learn more and support her efforts through the film's IndieGoGo page.

From what I know about Cleo -- and I have learned so much from her -- she will not stop. In her drive to claim her space and to be seen, she has undertaken a solitary and selfless mission to move all of us forward. In a very real sense, she has given everything. It is now time for us, the true beneficiaries of her actions, to pitch in.

DENVER DAVID ROBINSON has traveled to Uganda since 2008 and is currently working on a manuscript about his experiences there. His work has appeared in The Advocate and Advocate.com, Portland Magazine, The New York Times, and other publications. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

See Cleo's award-winning essay and portrait, and preview The Pearl of Africa, on the following pages.>>>

Photo by D. David Robinson (c) 2015, for use by The Advocate with this article only. All rights reserved. Subjects have approved use of images contained herein.

Cleo Kambugu, then a 26-year-old transgender woman (originally published in 2014)

My name is Cleo Kambugu, and I work with Trans Support Initiative Uganda. This is one experience of my life as a trans woman in Uganda. Not every day is like this, but because of events like these, my kind and I smile and celebrate like there's no tomorrow. For some of us, there isn't. That is our reality.

I wondered how the evening's events [when she was attacked by a mob] had brought me to this dark moment. The mob gathered and swelled by the second, people drawn by curiosity and by the insults the dark man spewed at the girl. I raised my head, and in the distance I could see the silhouette of a man I recognized as my boyfriend. He was upset, trying in vain to draw the mob away in his calm, true way. I pressed my hands hard against my ears, trying not to hear the insults -- each was a blow.

I receded into a world of my own -- my utopia -- only to be pulled back by the gentle touch of an old man, a security guard. His silvery, teary eyes met mine. "Please come," he said. "Let's leave this place, my daughter."

He called me his daughter, even after everything he had heard. He understood what these men failed to recognize. My knees gave way and I broke down; I cried, I wailed. The man's kind words went deeper than the blows and insults, and worked quickly to patch my heart. He drew me to my feet. "There, there ... there, there." And then, like a storm drained of its energy, the mob quieted and dispersed -- all because of the tenderness of an old man, a stranger to me.

Sitting in my room this morning, going over all the events of last night, I can't believe I made it -- that I'm even alive to tell this. Until yesterday, I thought my heart was armored in steel, finally indifferent to the transphobia that is so true of my motherland.

But this event reminds me that I am still human -- still flesh and blood. I survived to tell my story and it is my job, my passion, to do so. This experience pierced me to the core, and turns out to be just that spark I've needed to get to the next level in my work. I finally understand the need to do this like I've never understood it before.

My work will not be done until we finally have a gender-neutral society here in Uganda, one in which every gender is liberated and accorded the same respect and treated with equality. Join me if you believe in my cause.

Preview The Pearl of Africa on the next page.>>>

Chapter 1: The Bill

Chapter 2: Right to Love

Chapter 3: Family

Chapter 4: Nelson

Chapter 5: Evolution

Chapter 6: Far From Home

Support The Pearl of Africa's completion through the documentary's IndieGoGo page here.