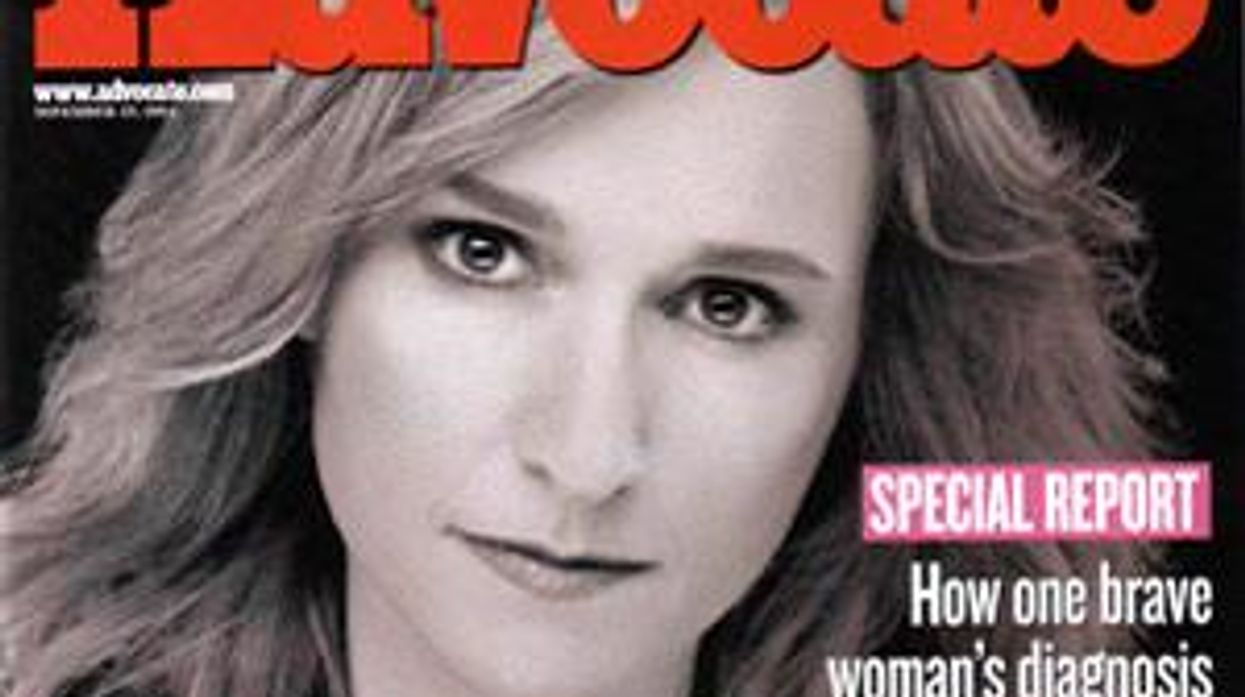

Just minutes after rocker Melissa Etheridge posted notice on her Web site October 8 that she was being treated for breast cancer, her message board was bombarded with hundreds of supportive notes from fans. "Wow, I didn't see this coming," the singer responded, writing about her diagnosis on the site. "What an unexpected journey this is." In an instant, Etheridge had brought cancer into the nation's headlines. What impact her diagnosis will have on the health of lesbians remains to be seen, but the news came as a shock, particularly since Etheridge is only 43. (Still recovering from surgery, Etheridge had granted no interviews at press time, but she did approve of the use of her image with this story.) "Hearing about Melissa's diagnosis gave me a jolt, as I'm sure it did to a lot of lesbians," says Alison Bechdel, author of the "Dykes to Watch Out For" comic strip, which features a lesbian character with breast cancer. "I think we tend to be pretty much in denial about breast cancer until it touches our lives directly. Even among the out activist lesbians I know who are very educated about breast cancer and prevention, it's a threatening topic. So I think the fact that everyone knows Melissa will definitely get us talking more and, hopefully, dissipate the fear and denial a little bit." Adding to many lesbians' fears is the fact that they've come to believe their risk of developing breast cancer is much greater than that of heterosexual women. It is true that studies have found that some risk factors for breast cancer--such as being overweight, smoking, and not having given birth or breast-fed--are more common among lesbians. But a recent study that compared differences in risk factors between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters did not find much disparity at all. "What we found was that the risk was about 1% higher in lesbians," says Suzanne Dibble, cofounder of the Lesbian Health Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and a lead researcher on the study. But even if the risk is higher, that doesn't mean more lesbians will get breast cancer, she notes. Women with many breast cancer risk factors don't always get the disease, while some women who have none of the known risk factors do. Noelle Mayhew was diagnosed with breast cancer in July 1999 at age 32 and "was totally blown away," she says. Mayhew had gone to see her doctor after she began experiencing pain in her right breast and "thought of cancer as an old ladies' disease. Also, when you hear 'cancer,' the first thing you think is, I'm going to die." Following her diagnosis, Mayhew had a modified radical mastectomy followed by chemotherapy and radiation. Over the next several years it appeared her cancer was gone. Then in May she learned that the cancer had returned and spread throughout her body. But even that news hasn't dampened her spirit. Mayhew, who is a buyer for an arts and crafts paper store, is grateful for the support of her family and friends. In fact, on the day that she spoke to The Advocate, her mother threw her a surprise party at work. She mentions that she is single but is dating. And she's now in an 18-month clinical trial that is designed specifically for women with metastatic disease that is testing a new way to treat cancer. She says, "I don't plan on going anywhere." "You have breast cancer" are undoubtedly four of the scariest words a woman can hear from her doctor. And about 216,000 women in the United States will receive that news in 2004. All women are at risk of developing breast cancer; statistics indicate that the older a woman gets, the greater her chance of developing the disease. Approximately 77% of incidences of breast cancer occur in women 50 and over. It is estimated that 40,110 U.S. women will die of the disease this year. "We need to get lesbians into routine screening because when a woman is diagnosed early her chances of surviving are much higher," says Ellen Kahn, director of the Lesbian Services Program at the Whitman-Walker Clinic in Washington, D.C. "At this point, everyone knows someone who has or has had breast cancer. It's not a foreign or intangible reality. Yet there remain lots of personal reasons why folks delay mammograms or don't do breast self-exams." The good news is that more women are now being diagnosed early, when the disease is more easily treatable; options for treatment have improved; and many more women survive breast cancer than die from it. "We cure two thirds of breast cancer," says openly gay breast surgeon and women's health activist Susan Love. "And when I say 'cure,' I mean that most women who have had breast cancer will not die from it. Further, even once breast cancer has spread to other parts of the body, women can live for a long time with the disease. "There has been more research on breast cancer than probably any other cancer," Love continues, "and that, in part, is thanks to the efforts of many women. We've made a lot of progress in treating breast cancer, but what we really need to learn how to do now is to prevent breast cancer from happening."

Another important factor that determines whether women will be diagnosed early, when the disease is most treatable, is access to care. But research shows that lesbians are often worried about encountering homophobia in the doctor's office; they are also less likely to have health insurance. And not having regular access to care, which keeps women from having annual mammograms or clinical breast exams, can delay a breast cancer diagnosis. Annie Shaw, a 57-year-old lesbian, knows this firsthand. Shaw's mother and three maternal aunts all have had breast cancer. And she works in the Lesbian Services Program at the Whitman-Walker Clinic. But a negative experience with getting a mammogram in 2001 when she didn't have health insurance kept her from getting the routine care she knew she needed. "Even I, who knew better, couldn't call and make the appointment," says Shaw. "I even have a partner who was going to a breast surgeon every six months" because she had had a suspicious biopsy. "So I should have been first in line. But the reality was, my own fears or my own shame kept me back." Shaw finally went for that mammogram in August. She had breast cancer. She had surgery to remove the two tumors that were found, and she will soon begin chemotherapy and radiation. The diagnosis has been hard, but Shaw says she's pleased that she found a lesbian-friendly surgeon who put her at ease by expressing concern for both her and her partner. "My doctor told me that she thinks a breast cancer diagnosis is harder on female partners than on a husband," Shaw says, because "it puts partners in touch with their own fear of having breast cancer. And for my own partner, that has been true." How individual lesbians view their breasts can also affect how they handle a cancer diagnosis. "I've heard plenty of butch lesbians who've had breast cancer or are at high risk for breast cancer say that they are more than happy to have their breasts removed because they don't want them and never wanted them," says Jessica Halem, executive director of the Lesbian Community Cancer Project in Chicago. Yet, she notes, there are other lesbians--butch and femme alike--who feel their breasts are an important part of their sexuality and who choose treatments that will allow them to keep their breasts or who decide to have reconstructive surgery. "I still have both of my breasts. and whether I will keep them is a bridge I have to cross later," Etheridge wrote to fans in the days after her surgery. "They took out the tumor and a few lymph nodes, only one of which was positive...the sentinel node (for those that know breast cancer- speak). After that my margins are clean!" At press time, the singer was home recovering with wife Tammy Lynn Michaels, who has also declined to speak to the press. Etheridge's diagnosis came after she discovered a lump in her breast. For Vernita Gray, it was a friend's insistence that she get a mammogram that might have helped save her life. She had a family history of breast cancer--her mother, grandmother, great-aunt, and cousins had all been diagnosed with the disease--but had not had a mammogram in over a year. When she did, in November 1995, at age 47, she was diagnosed with cancer in her right breast. Over the next eight years, it appeared that her cancer was in remission. Then in September 2003 another mammogram showed that she had a tumor in her left breast. Gray decided to have both breasts removed and to have immediate reconstructive surgery. Initially she wasn't going to have the reconstructive surgery. "It was a challenge for me as a butch lesbian," she says. "But I'm glad I did it. I swim a lot, and I feel comfortable wearing a swimsuit. And that's important to me." It's been a year since Gray's surgery, but she still needs to have two more surgeries on her breasts--which she calls "my new girls"--before the process will be complete. "It's been a long and incredibly painful process," says Gray, who is the GLBT liaison in the Cook County state's attorney's office in Chicago, "but I've been an activist for 35 years, and I'm still doing my work in the community."

Gray's second diagnosis led to myriad other changes in her life as well. "My breast specialist said to me, 'Let's take a look at your lifestyle,' " says Gray. So she did. Soon she was working out regularly, had changed her diet, and was no longer the bar dyke she once was. Now, she says, on Friday nights, instead of sitting at the bar breathing in other people's cigarette smoke, "I'm at my local health food store buying tofu and nitrate-free bacon and then heading home. I hardly recognize myself." Health advocates would like to see more lesbians adopt such overall lifestyle changes. They hope Etheridge's diagnosis not only draws attention to breast cancer but increases awareness about broader health issues. "It's more complicated than just saying, 'Go get a mammogram.' We need to talk about health as a way of life," says Halem. "We have moved to a place where our loudest cry is for every person to have a strong, positive relationship with a [health care] provider." Mary Dzieweczynski, executive director of Verbena, formerly the Seattle Lesbian Cancer Project, agrees. "My concern," she says, "it that we take a specific incident such as someone like Melissa Etheridge being diagnosed with breast cancer and put it in the larger context of health disparities and health justice and how that plays out" among lesbians. She and her group want women to understand that wellness is pride, she says: "We want gay pride to be connected to taking care of yourself." In the short term, though, when people think about Etheridge they are undoubtedly going to think about her struggle with breast cancer, and her fans are already trying to move that awareness into action. Virtually overnight a group of women who met on the MelissaEtheridge.com message board organized a fund-raising campaign called the Pink Bracelet Fund. Taking inspiration from the hugely popular yellow live strong bracelets sold to support the Lance Armstrong Foundation, the pink bracelets feature the breast cancer ribbon and say BE STRONG--mle . As of October 20 approximately 13,000 bracelets had been sold worldwide, and coordinators of the fund-raiser report the bracelets continue to sell at a rate of 1,500 to 2,000 per day. At Etheridge's request, all of the proceeds raised will be donated to the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation. Lesbians who have had cancer say they hope that Etheridge will continue to be an active voice. "I know if Melissa speaks out, it will really help," says Shaw. "Especially if she were to say, 'If you enjoy my songs, go get a mammogram.' Sometimes it takes someone famous to get you beyond your own inertia or fear." Seven days after announcing that she had cancer, Etheridge posted a second letter on her Web site, letting her fans know that she is recovering from surgery at home in Los Angeles and thanking them for their concern and activism. "Thank you for organizing and making those bracelets. I am humbled by your love and caring," she wrote. "I will be entering the phase of chemotherapy next. Who knows what that will bring. I will be writing songs for the greatest hits album and after...(the Pink album, maybe?) I will be working on the pilot for ABC and hanging with Tammy and the kids. I imagine you will see me again around the beginning of the year."