There's a scene in Eating Out, a sweetly raunchy indie gay sex comedy currently working its way through art-house theaters, that arguably sums up in one broad stroke the progress American queer cinema has made in the past 15 years. Hunky small-town college students Marc (Ryan Carnes) and Caleb (Scott Lunsford) are out on a date, and they've made their way to the local video store--which has a section devoted exclusively to films of "gay/lesbian interest." There was a time when such a scene would have been a laughable fantasy, but when Eating Out's writer-director, Q. Allan Brocka, scouted his Tucson setting for locations he found "an actual video store that really did have a sizable gay and lesbian section. It was really great to see." That section is about to get a whole lot bigger. Eating Out is just one of a sudden bounty of gay- and lesbian-themed American films coming soon to theaters near you, ending a multiyear drought that had many GLBT moviegoers latching on to the likes of Finding Nemo and The Lord of the Rings for their queer image satisfaction. OK, it wasn't quite that bad, but it's not an idle complaint. "We're an inherently invisible community. Film and video make the invisible visible," explains Stephen Gutwillig, executive director of Outfest, Los Angeles's international gay and lesbian film festival. In a nation facing a mounting bramble of questions surrounding free expression and gay rights, a surge in gay representation in this country's biggest export, the modern motion picture, is certainly worth celebrating--and worth some healthy scrutiny as well. "What's notable about this year's collection of high-profile [domestic gay-themed] films is how they illustrate the different ways that films are being financed and distributed," notes Gutwillig. "It's a nice range of star-driven stuff, full-on indie stuff, emerging filmmakers, established filmmakers, start-up distributors, and well-known industry players." Of course, this kind of excitement has happened before. In the early 1990s, independent cinema was electrified by a bumper crop of gay-themed films--including Todd Haynes's Poison, Gregg Araki's The Living End, Tom Kalin's Swoon, and Rose Troche and Guinevere Turner's Go Fish, to name just a few--so artistically bold and brimming with urgency that they were considered a full-fledged movement, dubbed the "new queer cinema" by renowned film critic and feminist academic B. Ruby Rich. Then...things just fizzled out. None in this pink pantheon made much of a dent at the box office, and most of the directors eventually moved on to other subject matter. Even when one did readdress the gay experience, like Haynes in Far From Heaven, it was typically as part of a much larger whole. But the foundations were laid. Brocka singles out Poison in particular as a powerful touchstone in his development as a filmmaker. "Seeing a film that was just so queer but so not, at the same time, was this voice that I'd never heard," gushes Brocka, who is also an occasional Advocate columnist. "I felt like I related to it on so many levels--it was a huge inspiration for me." So much so that the last thing he expected his feature debut to be was a film like Eating Out. Brocka says he wrote the movie on a lark while attending graduate film school at California Institute of the Arts, structuring it like "the films I liked of the '80s, like John Hughes films and the college sex comedies." See if this sounds slightly familiar: Shy jock Caleb is actually straight, convinced by his gay roommate, Kyle (Jim Verraros), that playing gay to date music major Marc is the best way to snag Marc's cute roommate, Gwen (Emily Stiles)--a love quadrangle completed by Kyle's long-standing, unrequited crush on Marc. If that's confusing, it's actually kind of the point. College sex comedies, remember, are supposed to feature love connections tangled by high-concept deceit; otherwise there's no movie. Not that Brocka ever thought he'd actually make the film. "I never thought I'd do anything with it," he laughs, "because it was so trashy, not really that deep, and it was a genre movie.... I hadn't seen many gay films that were genre movies, meaning like a gay horror movie, a gay Western, a gay college sex comedy, a gay spy movie--and now we've got one of each." No kidding. In fact, it's a major factor that gives Gutwillig hope that 2005 isn't just an "anomalous boomlet" in queer films. Eating Out is one of several movies this year that could essentially be called "gay and ___." These films take Hollywood genres as old as the movies themselves and reconstitute them with gay characters and gay-themed plotlines. The first out of the gate, the "gay spy movie" D.E.B.S., debuted in March, and it's highly doubtful there'll be a better cinema success story, gay or straight, this year. In fact, if it was a movie, you probably wouldn't believe it.

Angela Robinson grew up wanting to direct big Hollywood movies--not exactly an easy thing for an African-American lesbian to achieve. "I loved movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark and John Hughes movies," she remembers, "and I always wished the movies would turn out differently. I was always reimagining that Molly Ringwald got together with Ally Sheedy or something." About three years ago a friend told Robinson about POWER UP, a Hollywood networking organization that gives grants to lesbian filmmakers to make short films about the queer experience. So she submitted D.E.B.S., a kind of "Charlie's Angels in a boarding school" satire in which one of the good girls falls in love (and into bed) with their female archnemesis. POWER UP gave Robinson $20,000 to make it. When the 11-minute short debuted at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival, it was such a hit that Sony-owned studio Screen Gems hired Robinson to remake D.E.B.S. as a feature-length film for $4 million, lesbian plotline and all. Robinson, whose next project is--get this--Disney's summer family comedy Herbie: Fully Loaded with Lindsay Lohan, chalks up her success with D.E.B.S. to entertaining her audience above all else. "Many people have been like, 'Oh, I don't think your movie's a gay movie,' " she says with her ever-pleasant laugh. "And I'm like 'That's great!' Because it totally is. For me, I feel like I get to have my cake and eat it too. It's something that is one step removed from, 'this is just a gay story.' " Count B. Ruby Rich as one of Robinson's fans. In fact, she happily owns up to consuming her share of salty gay popcorn: "Hey, I sit around and watch The L Word on Sunday nights too." But she also expresses some concern that gay and lesbian audiences cannot subsist on popcorn alone. "Fine, let people explore genre," Rich says. "But that doesn't mean that I'm automatically going to be interested." Her fear, Rich explains, is that pop movies like Eating Out, D.E.B.S., and June's gay horror film HellBent will siphon gay audiences away from more challenging films like Tarnation, Jonathan Caouette's highly acclaimed kaleidoscopic autobiography that barely got distributed last year even after queer cinema luminaries Gus Van Sant (My Own Private Idaho) and John Cameron Mitchell (Hedwig and the Angry Inch) put their names on it as executive producers. "A lot of audiences for the new queer cinema were not there because they were so excited about the aesthetic breakthrough," Rich says with a tinge of resignation. "They were there because it was the only place they could find gay content. It's a fickle audience, and if they can find it somewhere else and it goes down easy like classic Coke, they'll take it. I want them to be pushed." She's not the only one. Mitchell also laments the shift in gay cinema toward more mainstream storytelling tropes--although he does understand the impulse of up-and-coming gay filmmakers to move away from the standard gay coming-out story. "Maybe that's part of the growing-up of gay-themed films," he ponders. "You move on from coming out. I think of [coming-out] films as almost traditional gay folk music or something. It's like, 'Oh, that song again.' You can [sing] it well, or you can sing it badly, but to me, it's a little bit tired." Mitchell is not just concerned about stereotyped gay story lines; he's also worried about stereotyping gay audiences. Take the hankie code gag in Eating Out, for example. In one scene a leather-bedecked gay couple snickers at faux-gay Caleb because he's unwittingly put a brown bandanna in his right back pocket--a ribald joke even some gay men might not get. This scene and others like it, written specifically and exclusively for a gay audience, strike a nerve with Mitchell--and expose a tricky fracture within the world of gay filmmaking. "To me, whenever you assume that because you're gay you're going to like this, it's condescending," sighs Mitchell. "There are people I know who cannot bear to see the next Latter Days [the popular 2003 gay romantic comedy set largely in West Hollywood, Calif.] because they know it's going to be dumb. Not everybody likes that kind of music; not everybody likes gym-distended bodies; not everybody is into Britney Spears." Latter Days, it so happens, was the first feature from Funny Boy Films, founded two years ago by entrepreneur Kirkland Tibbels in order to produce exactly the kind of positive, heart-on-sleeve gay-themed movies that have become old hat for observers like Mitchell. "Studios don't want [this kind of movie] because of the subject matter, and the typical gay and lesbian distribution or production company doesn't want it because it's not edgy," Tibbels says in his winning west Texas twang. "I could put my hands on my hips and say, 'Well, some of us believe we've seen too many movies about the gay and lesbian community where we want to go home and slit our throats.' If you put a title on my section of this article, it would be 'Come on in, the water's fine.' " Tibbels says he's really not that upset; he'd just appreciate it if the gay filmmakers he so deeply respects would cut him a little slack. "You won't catch me throwing rocks at people who tell stories that make me want to go home and slit my wrists," he promises. "Because you know what? They got that reaction out of me, and that's their job." But Tibbels figures there's room for everybody. "We've got a lot of stories to tell, and now's the time to tell them." For the record, the upcoming project Tibbels is most excited about is not nearly as cheery as Latter Days: Sex-Crime Panic is the story of a '50s witch-hunt in a small U.S. town based on a nonfiction book (published by Advocate sister company Alyson Books).

Further proof that the social awareness of queer filmmakers has not been completely supplanted by bubble gum, Gregg Araki's dark and deeply moving Mysterious Skin is actually the one upcoming film everybody agrees they're most anxious to see. And yet, interestingly enough, it's a gay-themed film that its "new queer cinema" writer-director would just as soon not label "queer cinema," new or otherwise. "The problem with [that label]," Araki says, stressing that he's speaking only for himself, "is that there was a certain expectation that was put on us, that we were somehow the queer representatives, these spokespeople. I make films not as a propagandist but as an artist, as a means of expressing myself. My films are not about representing gay identity for anybody, really. They're just expressing how I feel." In a way, Araki is touching on one of the big questions for any filmmaker who's gay or lesbian: Is the label "gay filmmaker" too limiting? Mitchell seems to think so. His next film, Shortbus, has already won him some notoriety for his plan to shoot a narrative film with actors participating in actual on-camera sex. "I very specifically wanted to examine the love lives of people of all sexual denominations," he says. "Certainly, the film has a queer sensibility, but it's trying to find things in common in the variety, which I think has to be the future for gay-themed films. Otherwise you're a ghetto. Take advantage of your nonconformism. Use it." Brocka, currently putting the finishing touches on Boy Culture, a "gay Trainspotting with hustlers instead of heroin," takes a different tack. "It's really, really hard to make a film," he says. "And if I don't feel totally passionate about it, you know, screw 'em. If I'm making it, it's probably going to be gay. If I get ghettoized and all I can make is gay films from here on out, hey, I'm making films, and I can't think of a more exciting life. I'm making things I'm truly passionate about." As long as people see the films. One of the strangest phenomena about gay cinema, Outfest's Gutwillig is quick to point out, is that while GLBT film festivals are thriving--"There are more gay and lesbian film festivals than any other genre of film festival in the country and in the world"--gay-themed films in general do not see the kind of support at the box office that movies like My Big Fat Greek Wedding and this spring's Diary of a Mad Black Woman have received from their respective segments of the population (not to mention, ahem, The Passion of the Christ). Part of that may be the fault of the DVD. The same boom market that warranted an entire gay and lesbian section in Eating Out's video store is, in essence, making it easy for the gay consumer to skip the theater and watch a gay film in the comfort of her or his own home--something fewer people did during the heyday of the new queer cinema. Of course, Brocka points out that his movie probably wouldn't have been made at all if it wasn't for DVD. Produced for less than $50,000--and delivering a bang for the buck that would have been impossible before the recent revolution in cheap, high-quality digital filmmaking tools--Eating Out was budgeted specifically to make its production company, Ariztical Entertainment, a profit in the DVD market. The film wasn't even supposed to play in theaters, but its success last year on the international film festival circuit--where it won a fistful of "audience favorite" prizes--convinced the producers to book a limited theatrical run. Eating Out opened at San Francisco's Castro Theater on March 18 and quickly scooped up $17,500 in one weekend. It opened April 8 in New York and Los Angeles, with other cities scheduled for later in the spring. Still, Eating Out's big-screen success story is the exception among DVD-targeted productions, in part because a budget of $50,000, even superlatively used, is barely a budget at all, and marketing dollars and press coverage tend to favor higher-profile productions. Most DVD-only movies make barely a blip on the cultural radar, even among targeted audiences such as gays and lesbians. For any filmmaker serious about a healthy career in cinema, a successful theatrical release remains essential. "Most movies make their money in an urban market," Gutwillig says, which means gay movies have to prove successful in a few big-city theaters before they're booked into the smaller markets--months later, if at all. As a result, even profitable gay and lesbian movies don't make much of a box-office splash. The weekend that Eating Out grossed $17,500 on one screen, for example, fellow indie Diary of a Mad Black Woman earned an average of just $1,900 per theater--but by playing on more than 1,200 screens to a remarkably supportive target audience, it had raked in nearly $48 million in just 24 days. If more gay-themed films proved themselves able to generate Diary-like audience support nationwide, perhaps the new new queer cinema could graduate from a passing wave into a permanent flow of films. As Angela Robinson puts it, "If everybody went to see that scruffy lesbian feature and it made a gazillion dollars, they'd be turning them out in droves."

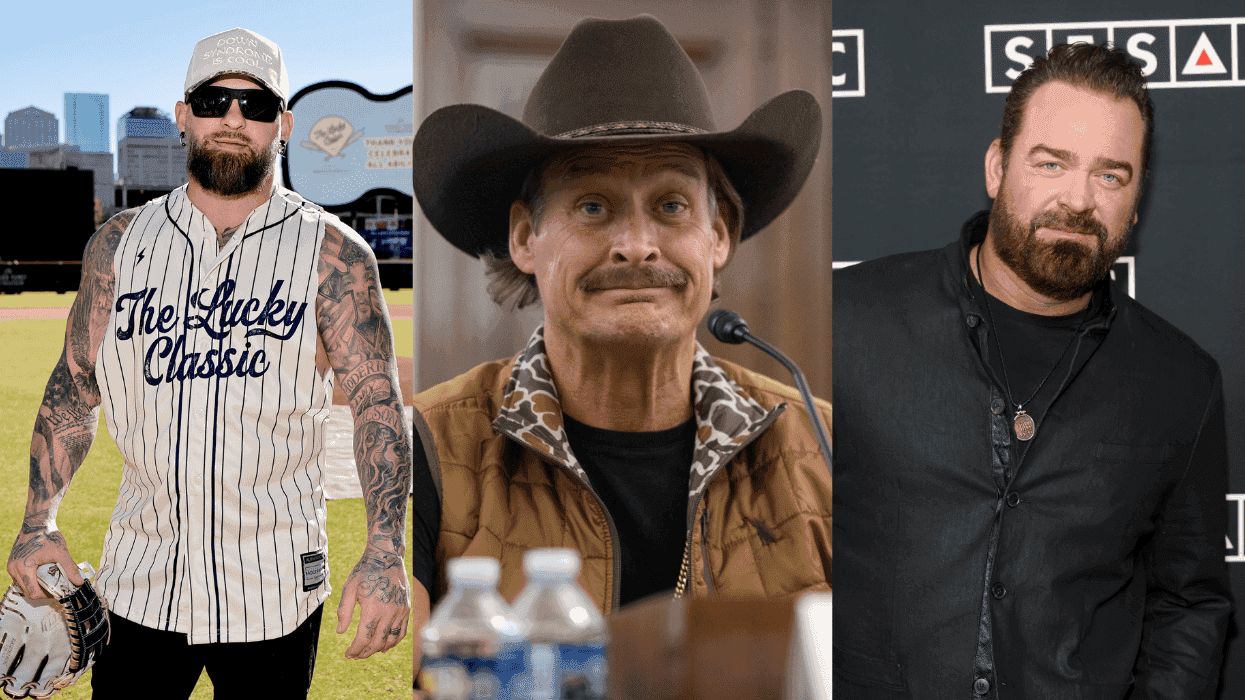

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.