As the world races towards a digital future, we're told that healthcare will become more accessible, more efficient, and more empowering—and it has, for some.

But for many young women and LGBTQ+ people in low- and middle-income countries, the reality is far more complex. The same tools meant to unlock opportunity also expose them to new risks and deepen existing inequalities.

In Kenya, a young mother faces a cruel choice: use her last few shillings to feed her children or buy mobile data to consult a health worker. In Colombia, a trans woman avoids making a medical appointment online because she fears being outed. In northern Ghana, a young gay man who urgently needs peer support and health advice online hesitates, fearing vigilante violence. These aren't isolated stories; they are part of a global pattern of exclusion and harm, as revealed by a major new international study of young adults navigating digital health in Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, and Vietnam.

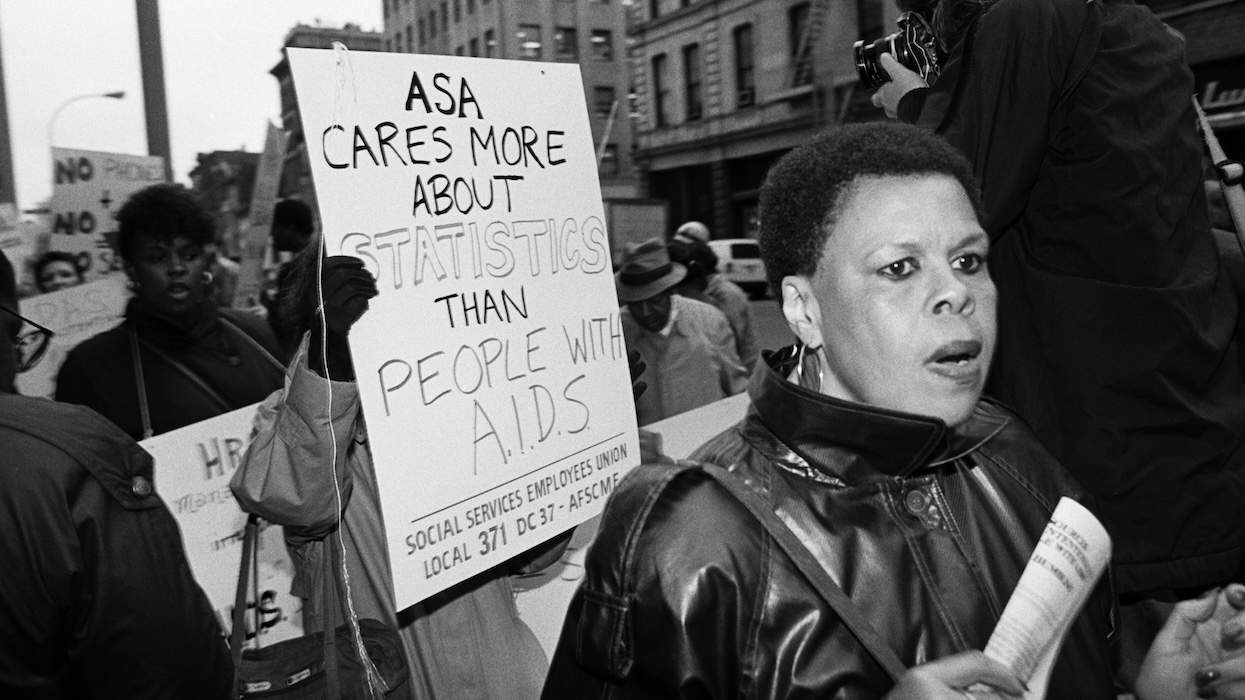

The report, "Paying the Costs of Connection," based on more than 300 in-depth interviews, paints a stark picture: as health systems go online, they frequently fail to reach the people they most need to support — those already pushed to the margins. For young women, LGBTQ+ people, sex workers, and those living with HIV, online access to healthcare is often filtered through economic hardship, surveillance by family or partners, and the looming threat of exposure.

For those who do make it online, the risks are profound.

In Kenya and Ghana, phones are commonly shared within households, and a single notification or text message can have devastating consequences. One Kenyan teenager was thrown out of her home at 14 after her father discovered her HIV status through a well-intentioned message from a health provider. Many LGBTQ+ youth and sex workers across the study reported living in fear of being outed by a search history, a data leak, or a misdirected message.

Three-quarters of those interviewed described some form of tech-facilitated abuse against themselves or peers: cyberbullying, stalking, image-based violence, or extortion. For many, reporting such abuse is not an option. In Colombia, trans women described facing humiliation or further violence when turning to the police.

In Ghana, gay and trans survivors of abuse who report it to the police risk being arrested themselves under anti-LGBTQ+ laws. Many said social media platforms repeatedly fail to act on reports. The message is clear: stay offline, stay silent, or risk everything.

And when people retreat from the digital space, public health pays the price. Many young LGBTQ+ adults said they become informal information hubs for their communities, especially for elders or peers without digital access. They are doing the work but without recognition, protection, or support.

Global policy responses continue to focus on individual responsibility: avoid clicking on suspicious links, use strong passwords, and exercise caution. But such advice is meaningless without addressing the deeper structures of inequality - poverty, misogyny, criminalization, impunity - that define who gets to be safe and informed online.

Meanwhile, governments in high-income countries are slashing development aid and retreating from commitments to gender and LGBTQ+ justice. Just when investment is most urgently needed, support is vanishing. The result? Digital health systems designed without those most in need may be widening the very divides they claim to bridge.

Produced by a coalition of community-led organizations, lawyers, academics, and activists supported by the University of Warwick, the Paying the Costs of Connection report is the most extensive community-led study of its kind. Its findings are not just a warning; they're a call to action.

We need laws that protect survivors of digital abuse. We need mental health support that affirms the dignity of every individual. We need transparency and accountability from big tech on online abuse. We need serious training for healthcare and law enforcement personnel, who too often meet disclosures with disbelief or disdain.

Voices is dedicated to featuring a wide range of inspiring personal stories and impactful opinions from the LGBTQ+ community and its allies. Visit Advocate.com/submit to learn more about submission guidelines. Views expressed in Voices stories are those of the guest writers, columnists, and editors, and do not directly represent the views of The Advocate or our parent company, equalpride.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.