Every time

President Bush makes an overture to Democrats--and he

makes plenty these days--conservative

Republicans get edgy. They fear he might be so willing

to cross the aisle that he will end up crossing them.

"Everybody should

be very concerned and very active," said Grover

Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and a

conservative leader with close White House relations.

"The temptation

for an administration in the last two years is to do

something for legacy purposes," Norquist said. "And with a

Democratic House and Senate, doing something cannot be

good."

The White House

sees it differently. Mired in an unpopular war, slumping

in the polls, and knocked off course by one setback after

another, Bush still has time. He can score a few

legislative victories and burnish his domestic legacy

before he leaves office if he gets help from both

parties.

Plus, he has

little to lose, not having to worry about an election ever

again. Now that Bush needs cooperation from Democrats to get

things done, bipartisanship is back in style.

"We have suffered

as a party from a perception that we're unwilling and

unable to get things done," said Ed Gillespie, a former

Republican Party chairman. "And so if there are some things

that we can do that are consistent with our Republican

principles, we should get those things done."

Since Democrats

won the House and Senate in November, Bush has appealed

to them on education, energy, health care, immigration, and

Social Security. That has kicked up whispers of

triangulation, a model linked to his predecessor,

Democrat Bill Clinton.

As designed, it

amounted to plucking ideas from the opposing party,

taking others from the president's own party, and offering

up a merged strategy that put the White House above

the fray. Even when it worked, it often led to both

sides feeling scorched.

Karl Rove, Bush's

chief political strategist, had been reassuring

conservatives that will not happen under this president. The

White House mantra is to work with Democrats without

abandoning such tenets as low taxes and personal

responsibility.

As Rove put it,

"We're going to operate around principles and see if

we can find a way to bring the broad center together with

us." Then he thought about those words and got more

precise about the middle ground: "Broad right center."

William Galston,

a top domestic policy aide to Clinton, said

triangulation was overhyped. In reality, he said, Clinton

worked with Republicans on matters such as overhauling

welfare, a campaign pledge, because his views meshed

with theirs.

Likewise, Bush

may have more in common with Democrats than leaders in his

own party on education and immigration. "The president now

has an opportunity to take yes for an answer," said

Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Access is not the

problem for conservative leaders. They regularly get an

audience with the White House through conference calls and

meetings, and a friendly heads-up when policy changes

are coming.

"I don't feel

like we've been cut out at all," said Rep. Jeb

Hensarling of Texas, chairman of the coalition of House

conservatives known as the Republican Study Committee.

"Ask me the same thing six months from now. But right

now, I think we have good dialogue."

Still, Bush has

not always been in concert with the base that helped get

him elected twice. Conservative Republicans have derailed

one of his Supreme Court nominations and chided him

for expanding government more than he has restrained

it.

On cultural

issues, such as Bush's opposition to abortion and same-sex

marriage, conservatives are not bracing for a fight. The

grumbles tend to focus on two bedrock issues:

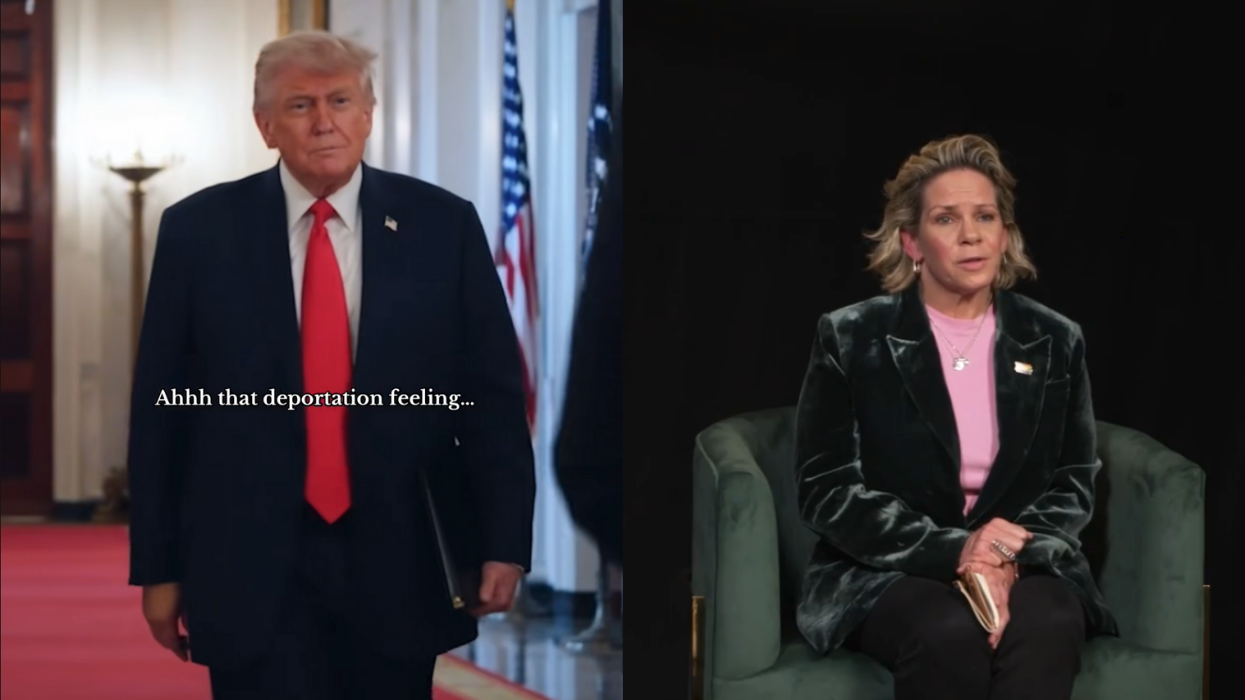

immigration and taxes.

Bush remains

adamant that immigration changes should include a

guest-worker program and a path to citizenship for illegal

immigrants. Many Republicans support that approach,

but conservatives say it is too lenient toward

those who entered the country illegally.

"House

conservatives will be exceedingly unhappy about anything

that has even a faint aroma of amnesty," Hensarling

said.

A stalemate,

though, does the GOP no good. Republican leaders fear their

party could splinter in the 2008 election year.

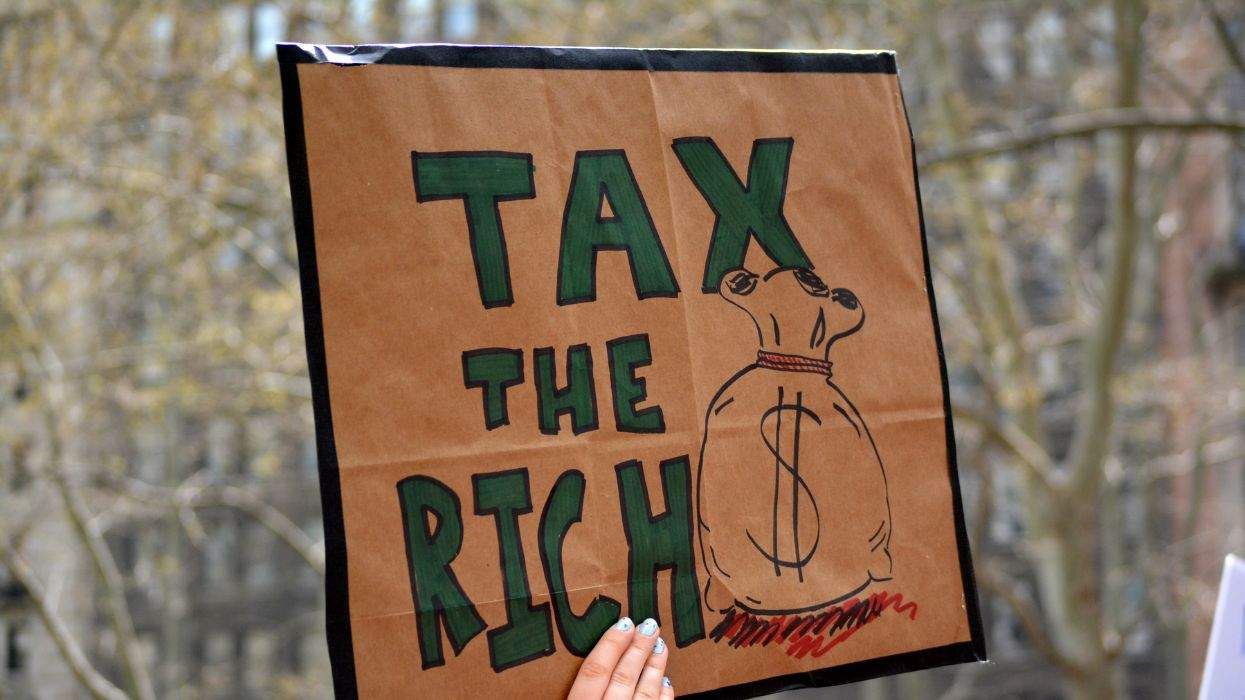

On taxes, the

president has put it plainly: "We're not going to raise

taxes." But the worries are not going away.

To entice

Democrats to negotiate on overhauling Social Security, Bush

has offered to meet without ruling anything out. Many

conservatives say nothing good can come from that;

they do not even want him in the room with Democrats.

Their nightmare is a deal in which taxes go up or

benefits go down to make the program more solvent, yet

without the private investment accounts that Bush

wants.

Some of this

unrest may be rooted solely in memories of disappointment,

Gillespie said.

Bush's father

famously broke his "read my lips" pledge against

raising taxes in a budget deal with Democrats. Republicans

had to work to halt President Reagan's tax deal with

Democrats in 1985, led in part by a Wyoming lawmaker

named Dick Cheney.

Norquist said the

pressure on Bush to give in to Democrats even one time

will be immense. Then again, Bush seems inclined to do more

than just say no, and he is running out of time.

"The president

doesn't have two years," Galston said. "I don't think

he has a year. He has about nine months before it's all

politics all the time. He has to decide how successful he

wants the remainder of his presidency to be." (Ben

Feller, AP)

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes