In the mornings I'd awake to the announcements in Turkish coming from the speaker above my locker at the foot of the bed. The announcement was foreign, invading my mind through my ears. Turkish noise. It blasted through my room, awakening me every morning. My cell was a room painted white with a pink wash, 8 feet wide by 10 feet long. My bed was a twin, cemented to the ground. Solitary confinement in Bakirkoy prison. Placed in a room alone because I am an out butch lesbian. A gender-nonconforming woman. The powers that be (The warden? The government? I had no idea) did not want me to be "disruptive" to the women's prison population, so they placed me in solitary, or so the two women from the American consulate explained to me my second day in. Ironic, given my belief that cunnilingus was invented in a women's prison.

Each day after the announcement I would drop my feet to the cold cement floor and walk six steps to a large window, almost as wide as my arm span, half as tall as me. The Mediterranean sun brightly shined through. A 30-foot gray cement wall surrounded me. A vertical side wall twice as tall as the Harlem brownstone I grew up in. As I looked up at the blue sky above the wall, the roar of a plane rumbled in my ear, preceding the joyful sight of a 747 flying through the sliver of sky I could see. As quickly as it entered, it disappeared. I thought, Someday I'm getting on that plane and back to the woman I love.

In 2009, I was living in Tel Aviv with my Israeli girlfriend when my uncle died. I attempted to take a trip to my hometown for the funeral. During a layover in Istanbul, I was stopped and frisked when I set off the metal detector for not taking off my jewelry. Nine grams of hashish (the length and width of a woman's middle finger) was found in my front pocket. Normally in Turkey the punishment for this transgression is a few hours in jail and immediate deportation. However, I was placed in prison. The two women from the American consulate were surprised that I was incarcerated. They'd never seen such a thing.

During the time I spent in solitary I learned that prison is designed to be a a dehumanizing experience that reduces people to one mistake, as in my case, or an alleged mistake that legitimizes their being treated like animals. Being locked in a cage, being isolated against your will from your family, being taken from your home, being deprived of basic liberties like talking on the phone and writing letters can do nothing to anyone but detach them from their own humanity. While I was incarcerated in Turkey I was bombarded with questions of if I'm male or female. I'm a butch lesbian. I sound like Vin Diesel. While outside of prison this draws a ton of curiosity, people take my word for it when I tell them that I'm female. This was not the case in Bakirkoy prison. It seemed impossible to satisfy my Turkish warden's inquiries on the matter.

The week I arrived I was taken to a room with an examination table and a cheap room divider screen. I was taken by a guard and a fellow prisoner/interpreter. The prison doctor, a potbellied, gray-haired Turkish man in a doctor's coat, questioned me through the interpreter.

"Are you male or female?"

"I have breasts," I jiggled them. The interpreter giggled. "I'm female."

"Are you male and became female?" asked the doctor.

"If I were male and became female I'd look like Beyonce or Heidi Klum. Not like a dyke from New York City." The interpreter blurted out laughter and repeated it in Turkish. That was the end of the visit. The doctor never physically examined me, which suggested that the point of the visit wasn't to find facts but to invade my privacy, marginalize me, make me feel like an "other." This was an example of the harassment and the humiliation that gender-nonconforming people are subjected to in prison.

A month later a young, pretty Turkish guard came to my room to escort me somewhere. Leaving my room was a joy, a mini vacation from the loneliness and regret I felt constantly. It'd been eight days since I'd left the cell. I normally sat around in boxers and T-shirts, so I quickly snapped on a bra, threw on sweatpants and headed out. She took me to a basement where a small van and four men with rifles awaited us. They handcuffed me in the back and off we went!

We arrived at a hospital, and I was escorted through it handcuffed and surrounded by guards -- one in front, one behind, and one on either side of me holding their rifles at attention. The pretty guard led the way. Although I'm a masculine woman, I stand 5 foot 3 and walk with a limp. At 120 pounds, I was hardly a physical threat. I felt like Hannibal Lecter as we walked past doctors, nurses, and patients in waiting areas. The guards took me to an ob-gyn. She was an olive-skinned blond, pleasant, in her mid-30s, and she spoke English fluently. She told me that 90 percent of Turkey was Muslim. She examined my outer genitalia and gave me a sonogram, which confirmed that I had a uterus. It offended me that Turkish authorities needed to look between my legs to confirm that I was a woman. It disgusted me, but what could I do? I was a prisoner.

Two and a half months into my stay and two weeks before my court date, my family hired a Turkish lawyer. I learned that the police officers who arrested me stated that I had hid 15 grams in my underwear. The hiding of drugs brought me up to the level of drug trafficker. My lawyer was convinced that I was racially profiled. It was the end of the month, cops have quotas, and most of the African women in Bakirkoy are in for drug trafficking. It was easy to make me one of them.

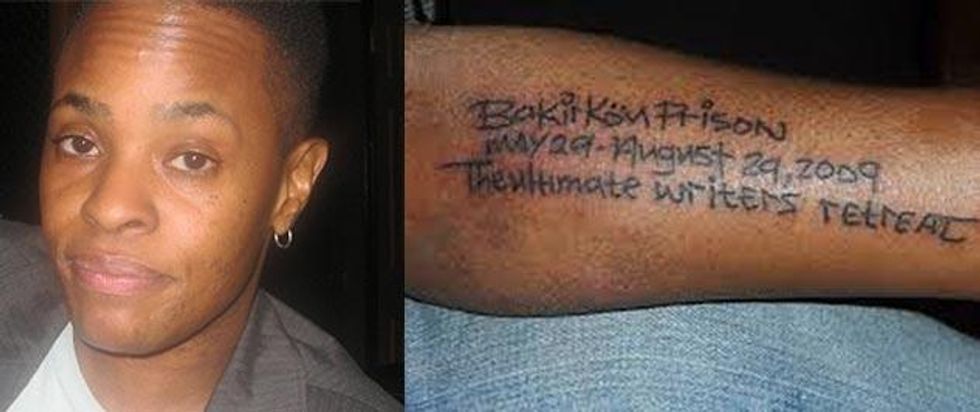

Although I was finally exonerated of the drug charges, I spent May 23 to August 23, 2009 in solitary confinement at Bakirkoy prison. It's hard to speak about the shame and guilt that I feel for the stupid act of traveling with drugs. The stupidity of what I'd done. The shame of being a girl from Harlem who has two parents and had attended Bank Street School for Children, Sarah Lawrence College, and the American Film Institute. I'd written a movie for Halle Berry at 20th Century Fox. I'm not the kind of girl who gets locked up for drugs. I'm not that kind of black person, yet here I was in Istanbul, being just another nigga. I had no business being there, but I had made bad choices that left me there. I made a mistake. In this case I more than paid for it because I am a black butch lesbian.

MAISHA YEARWOOD is a Harlem native and a Hollywood screenwriter who has been writing and developing sitcoms and feature films for 19 years. She has written and developed for Warner Bros., Fox Network, Disney, Nickelodeon, ABC Family, Artisan Entertainment, and Discovery Channel. She received her MFA from the American Film Institute and a certificate in screenwriting from the University of California, Los Angeles, Film and Television School. She lives bicoastally between New York City and Los Angeles. She is currently working on a transmedia project around her play 9 Grams. The play recounts her experience in solitary confinement in Istanbul. S. Epatha Merkerson is set to direct the play.