Omar Mateen was a monster. Attorneys for the Pulse shooter's widow never contested that over two and a half weeks of testimony in an Orlando federal court. But should Noor Salman suffer for the slain killer's sins?

Closing arguments today will cap off the only criminal trial stemming from the June 12, 2016 mass shooting, where 49 innocent people died and 53 more were injured at a gay bar on Latin night. Mateen died at the hands of law enforcement after a standoff at Pulse. Now, defense attorneys say Salman had no role in the attack, despite telling FBI agents in the hours after the massacre that she knew her husband was on the way to commit terrorism.

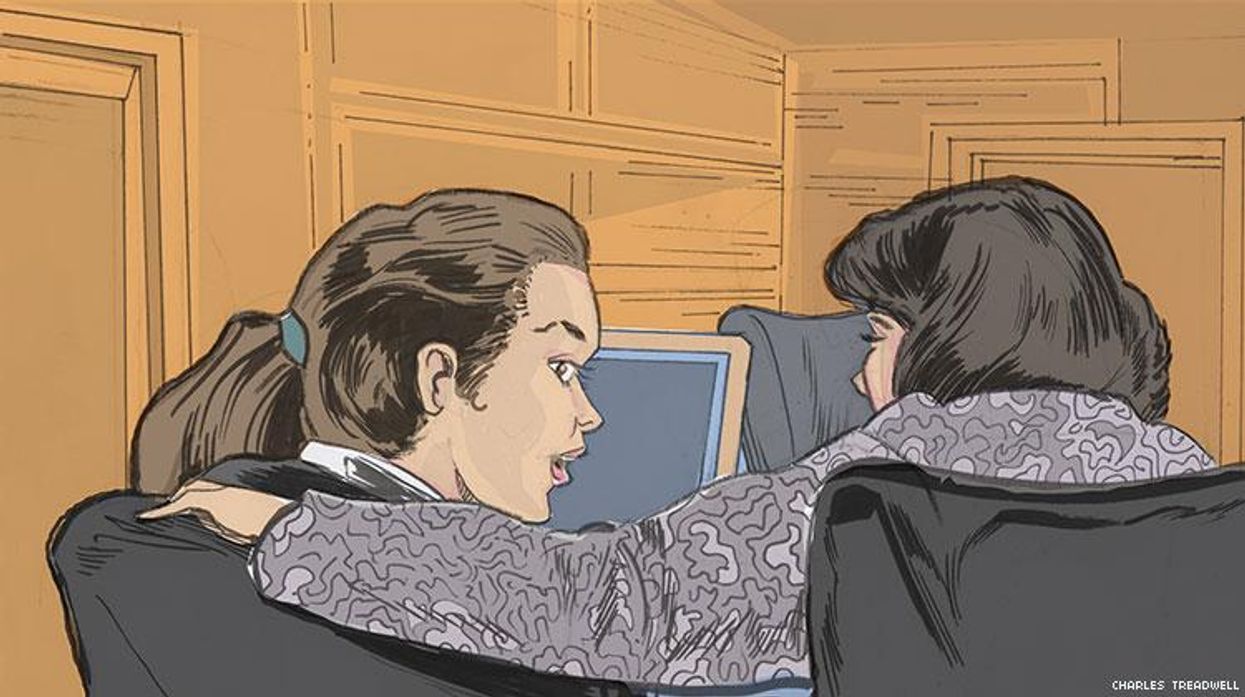

Defense attorneys on Tuesday brought as their last witness Dr. Bruce Frumkin, a clinical psychologist who interviewed Salman in prison. By his assessment, Salman suffers from a "significant mental disorder." The expert gave Salman a test in August to grade her suggestibility and she scored an 18, more than double the average score of 7.5, making her much more likely to acquiesce to leading questions. Frumkin also questioned the length of questioning. Salman ended up staying at FBI headquarters for some 20 hours for periodic questioning, none of which was captured on audio or visual recording. Frumkin testified any length of questioning beyond 4 hours should be considered excessive. Defense attorneys accused the FBI of employing the "Reid" method of drawing out confessions from interviewees. Frumkin followed that route as well, suggesting having a subject sign a statement written by someone else was part of questionable law enforcement tactics.

Before the trial, defense attorneys also filed assessments of Salman done while she was in custody that showed her to be of low intelligence, and suggested Mateen treated her abusively. Dr. Jacquelyn Campbell gave Salman an IQ test while she awaited trail at a federal prison outside Orlando, and tested her with an IQ of 84 (average for Americans is 98). "Noor Salman is a severely abused woman who was in realistic fear for her life," Campbell wrote.

In a written survey before the trial, Salman herself said she had been beaten by Mateen and that her husband threatened her life. Mateen raped and choked Salman, she said, and she feared he was capable of killing her.

Family for Salman say this line of defense has taken its toll on the defendant. Salman family spokeswoman Susan Clary spoke to reporters outside the courthouse, relating Salman's opinions of this defense.

"She told me 'People say I'm simple and I'm okay with that,' " Clary says of Salman. "But this trial has been so personal, putting things out there you and I would never want the world to know."

Yet Clary says it's conceivable Salman never questioned the incredible amount of spending Mateen did for his family in the weeks before the trial, including purchasing thousands of dollars worth of jewelry. Salman lived on a $20 allowance, and would probably be thrilled to be be given access to a bank account, something else that happened shortly before the shooting. Certainly, defense attorneys say a woman who expected her husband to soon be dead or in jail wouldn't have purchased Father's Day gifts to give her husband days before the shooting took place.

But the prosecution's case relies heavily on a statement in which Salman wrote herself that she's "lied to the FBI." And in cross-examining Frumkin, Assistant U.S. Attorney Sara Sweeney asked if a person of low intelligence could still give a true confession. Yes, Frumkin replied.

The rest of the prosecution's case largely centers on whether Salman texted Mateen with a cover story to tell family the night before the shooting. "If ur mom calls say nimo invited you out and noor wants to stay home," she wrote in a later deleted text. Salman appeared to misspell Nemo, a childhood friend of Mateen's.

Nemo, whose last name never was disclosed in trial, came to Orlando as a witness for the defense. He rarely spoke to Mateen in recent years, he says, because Nemo was busy studying at medical school in Washington, D.C. He did know, however, that Mateen used his name often. Whenever Mateen cheated on his wife, going out with Nemo served as a regular alibi.

Defense attorney Linda Moreno says jurors should question why, of all cover stories in the world that Mateen and Salman could cook up, would they use a tale Mateen regularly used to conceal his infidelity. More likely, Moreno suggests, Mateen used the lie one last time to deceive his wife about his whereabouts the night of the killing.

A crux of the defense from the start of the trial has been that Mateen did not choose the target of his attack until the early hours of June 12, 2016. Security footage shows he went to Downtown Disney in Orlando before heading to Pulse. And cell phone records show he went straight from Disney to EVE Orlando, a mainstream club downtown. Only after seeing security in both of those places did he drive to Pulse, and even as he shot up the gay bar, his phone continued trying to lead him to a different location.

Defense attorney Fritz Scheller in court read a letter from Pulse security guard Neal Whittleton, who wrote that Mateen asked, "Where are the girls at?" when he arrived at Pulse, seemingly unaware it was a gay nightclub. If Mateen didn't know anything about the Club, including how to get there, how could Salman have been in on the planning?

That's important to countering the statement Salman signed when with the FBI. Agents have testified Salman told them Mateen "likes homosexuals" even before learning Pulse was a gay club. She said Mateen looked at the website for Pulse and identified it as his target, even though no computer records for the Pulse website of Mateen's home computer can back up that claim. And she said she was with Mateen as he drove around the Pulse site a week before the attack, even though cell phone records indicate that trip never happened.

Regulars at Pulse have told media, including The Advocate, say he'd been at the club regularly for years. "He was one of my fans," performer Lisa Lane told The Advocate. But none of that came up in trial, where defense said the theory Mateen targeted gay people should not be allowed in court. Prosecutors focused on the shooting as a terrorist attack.

The biggest surprise in the last week of the trial came with the revelation that Mateen's father, Seddique Mateen, had been an informant with the FBI for 11 years, and that agents in 2014 considered grooming Mateen to be an asset as well. On Monday, attorneys delved into that ground with FBI Special Agent Juvenal Martin, who had worked with the father and interviewed Mateen when he was under investigation for terrorist sympathies years before the attack. Attorneys Charles Swift and Scheller argued in a motion on Sunday that this revelation alone, made only after the prosecution rested its case, was grounds for mistrial. But Judge Paul Byron said that this trial needed to be about Noor Salman, not Seddqiue Mateen, and denied the defense's motion.

Attorneys today for the government and Salman will make their closing arguments. Then it's up to a jury to decide whether to convict Salman of aiding and abetting a terrorist and obstructing justice. She could face life in prison if found guilty of the crimes.

Sweeney, in her rebuttal of the defense, says that many of the theories they have been put out about Salman's innocence rely on false presumptions. That Salman could not plan for an attack because she was simple and has a low IQ, for example, should mean nothing to jurors, she says, "Helping you husband in a mass murder is not something you have to be a genius to say no to," Sweeney said, while referring to Salman as cold, callous and caring for no one else, except maybe her son.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.