As acclaimed theater director George C. Wolfe sees it, this is the perfect moment for a new production of The Iceman Cometh to arrive on Broadway.

"It's about holding on to hope in a complicated time," Wolfe says of the Eugene O'Neill classic, first staged in 1946 and now playing in a Wolfe-directed revival starring Denzel Washington. "I think we're in that movie now."

Washington plays traveling salesman Theodore "Hickey" Hickman, whose twice-yearly visits are eagerly awaited by the denizens of Harry Hope's saloon and boardinghouse in downtown Manhattan, circa 1912. They are pretty much down and out, but they hold on to a shred of hope and dream of a better life. These dreams are unlikely to come true, but the folks at Harry's are assured of some relief from their painful existence when Hickey shows up to buy drinks, tell stories, and assure that everyone has a good time.

Not this time, though - Hickey has stopped drinking and gotten in touch with reality, and he's determined to make the men and women at Harry's see how hopeless their lives really are. "Hickey comes in to shower everybody with their ultimate truth and it ends up devastating them," Wolfe tells The Advocate via phone from New York City.

The message of the play centers on truth and lies, he says. "What proportion of truth and what proportion of lies allow one to wake up in the morning?" he says. "And what proportion of lies versus truth is delusional and keeps us stuck and not going forward? I think we're all asking those questions right now."

That's not only because of the current political environment, but also because of the overall environment in which many of us live, says the director. "When you're inside of a system that affirms who you are, you don't have to ask who you are," he says. "When you're inside of a system that questions you, then you question everything. And it brings out the best and the worst in people."

As a black gay man, Wolfe knows about operating in a system that doesn't affirm him. But it also helped him build what he calls "muscles" that have aided him in his career. Wolfe, born in 1954, didn't see much representation of his identities while growing up. "I would remember going, 'Oh, there's a black person on the deodorant commercial,'" he says, because that was so rare. But he could imagine himself in scenarios where he wasn't represented.

"You create this muscle called imagination ... where you find truth inside of stories that don't look like you and therefore it creates inside of you a muscle of empathy and identity," he says. "You learn very early on learn how you can exist in stories that aren't explicitly about you."

"When you write stories explicitly about you, it's fun and it's great because all of you gets to show up," he continues, "but when you work on projects that aren't readily identifiable as being an expression of who you are, you bring all those muscles that you cultivated when you were growing up and you apply those."

This production of Iceman has a black man, Washington, as a character usually imagined as white. Washington was already involved when Wolfe came onboard. The Oscar- and Tony-winner, last on Broadway in Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun in 2014, wanted to return to the stage in Iceman and was interested in working with Wolfe. But "he was the perfect actor to play this role" because of his "charisma" and "skill set," Wolfe says.

And the idea of the patrons of Harry Hope's looking up to a black man in 1912 isn't that far-fetched, he says. "They're all living in the same cesspool," he says, and then "Hickey comes along and he is a character of possibility, of savvy, and from their perspective, of sophistication and worldly accomplishments."

"So he is a black man and he is also put in a separate category," Wolfe explains. "People of accomplishment are placed in a separate category and we view them differently."

The production has been well-received, with mostly positive reviews and eight Tony nominations, including Best Revival of a Play, Best Direction of a Play for Wolfe, Best Actor in a Leading Role for Washington, and Best Actor in a Featured Role for David Morse, Washington's onetime St. Elsewhere castmate, playing disillusioned anarchist Larry Slade. (The awards will be presented June 10.) The cast features many other well-known actors, such as Colm Meaney, Bill Irwin, Neal Huff, and Dakin Matthews.

Wolfe has had a long and distinguished career, with numerous awards to his name, and a tenure as producer of the Public Theater and the New York Shakespeare Festival from 1993 to 2005. When asked if he has a favorite project, he can't pick just one.

"Angels in America was the perfect play to be doing in the '90s, when it was done, because what was happening onstage was what was happening in life," he says of Tony Kushner's two-part opus about the AIDS epidemic. Jelly's Last Jam was special to him because it was his first Broadway show, Bring in 'Da Noise, Bring in 'Da Funk because of the collaboration with Savion Glover, and, particularly, Shuffle Along because it was lighthearted and closed prematurely for reasons that had nothing to do with its artistic merits. (Producers decided to close the show when star Audra McDonald went on maternity leave rather than replace her.)

Then, in 2011, he directed the first Broadway production of The Normal Heart, Larry Kramer's drama about the early days of AIDS that premiered off-Broadway in 1985. "That ended up transformational for a series of reasons," he says. It was fascinating, he notes, to see the different meanings it had for people who had lived through the height of the AIDS crisis and for younger audiences, for whom it was "not so much a history lesson as 'What was it like back then?'"

And while it's not a play with which one would associate humor, Wolfe does have a humorous story about it. When protagonist Ned Weeks meets Felix Turner, who will become his lover, Weeks tells him, "I'm in the book." That, he says, led some young men in the audience to ask, "Was there a book that listed every homosexual?" The book to which Weeks refers is, however, the phone book, something unfamiliar to many younger people.

Iceman has a limited run; it's set to close July 1. Wolfe, who says he's been obsessed with "presentational" storytelling for as long as he can remember - to the point that, according to his cousins, he gave them lines to say when they played house - isn't sure what his next project will be. But there are many options. He's doing some writing, thinking about some film and TV projects, and also about some plays and musicals. He's in a mode, he says, of "what the hell, I don't know, oh, my God, I'm overwhelmed, oh, that's a possibility, let me think about that, that could be fun." But, he adds, that's a mode he enjoys.

The Iceman Cometh is currently onstage at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in New York City. Find tickets and information here.

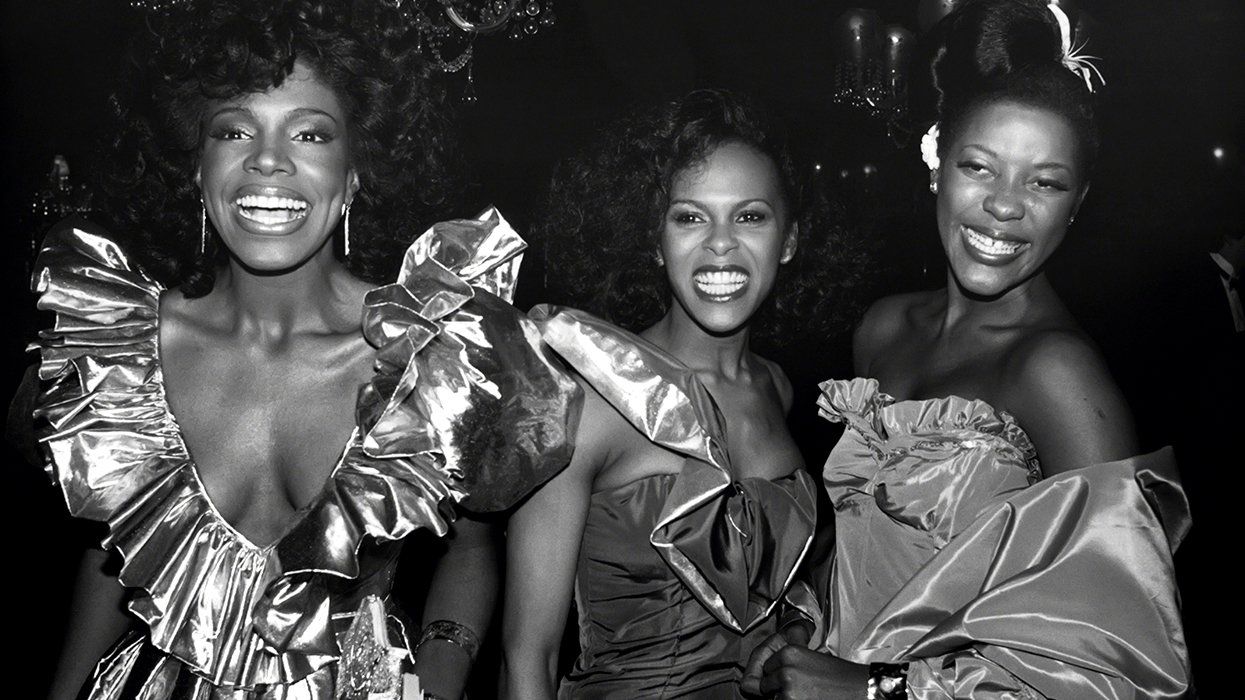

Colm Meaney (center) and the company of The Iceman Cometh.