In the summer of 1986, we left the projects.

Mama held down two jobs at the main hospitals in Hot Springs. By day, she delivered food trays to patients at one, and she worked by night as a monitor technician at the other.

We moved into a quaint ivory house on Baker Street, just off Grand, the main drag. The porch was wide and screened in. The living room had a brick fi replace. French doors led to a dining room with large windows, and sunlight flooded the space. Push past the swing door and the kitchen was bright, with a window over the sink and several in the breakfast nook.

There were three spacious bedrooms. Reagan and I bunked again. Just behind the house was a tiny, two-room maid's quarters attached to the garage, with a toilet that didn't work. Reagan and I converted it into a playhouse, where we entertained ourselves with Monopoly and other games--until we inevitably got on each other's nerves and started fighting.

Decades before, well-to-do white folks filled the neighborhood. The Colonial- and Victorian-style homes were still nice and stately by the time we moved in. Our neighbors, whom we never knew, were mostly retired, standoffish, and white. The block had an antiseptic feel and looked like the set of a TV sitcom. No funk. No badass kids running up and down the street. No projects divas strolling around in tube tops and denim cutoff s or screaming out of windows and doors. I was relieved.

Dusa still worked at Taco Bell, and her commute by bus to Hot Springs High School was shorter. Reagan and I transferred to Jones Elementary, which was about three short blocks away, and we walked to school. It also was around this time I wanted to exit my cocoon and interact with other kids, but nothing changed at Jones. Aside from multiplication tables, I learned a new word: f****t.

On the playground one day I found the nerve to approach a group of four black boys.

"What y'all doing?" I asked.

They looked at one another and laughed. The tall one, whom I recognized from the class across the hall from mine, glared at me.

"Listen at you. 'What y'all doing?'" he said in a voice pitched a few octaves higher as he batted his eyes and put his hand on his hip.

"I don't talk like that," I shot back.

"Yeah, you do," said the tall muthafucka.

Another guy, scowling, spat his words: "You act like a f****t."

The boys all laughed and walked off . One shouted back, "Stay away."

I stood there, my face flushed and a cyclone whirling inside my stomach. Later that evening I went into Dusa's room, where she lay across the bed doing her homework. She looked up. "What you want? Get out."

"What's a f****t?"

"Uh-uh."

"What?"

"Where you hear that?"

"At school. These boys called me a f****t.

"Well. That's what you get."

"I didn't do nothin'."

"Dusty, I been tellin' yo' ass for the longest. Boys who act like girls? That's a f****t. Got it?"

I was confused and tried to hold back the tears but was unsuccessful.

Dusa rolled her eyes.

"See? That's what I'm talking about. You so need to get that together, Dusty. Get out."

"I didn't do nothin'."

"Get out!"

I turned around. Maybe she was right. I needed to find an edge from somewhere, but I wasn't tipping out of my cocoon for it.

Dusa told Mama about the f****t incident, and she called me into her room a few nights after Dusa kicked me out of hers. Mama didn't look at me as she clipped foam rollers into her hair.

"Yeah?"

"You havin' problems at school?"

"No."

"You lyin'?"

"No."

"Why Dusa tell me boys are callin' you a f****t then?"

I looked at the floor and didn't answer.

"Huh?"

I mumbled, "I don't know."

"Yeah, you know." Mama's tone was accusatory.

I said nothing, and the tension pulsed for several seconds.

"Dusty, I'm talkin' to you."

"Don't cry," I told myself. I concentrated on the hardwood floor. Maybe if I looked at it long enough, hard enough, I would melt into it. Or magically crumble like unbleached flour, leaving a mess that somebody else (maybe Dusa) would have to clean up.

Or maybe I could just close my eyes and escape somewhere with Michael Jackson. I could--

"Dusty!" Mama's voice blared. "Look at me."

She put the comb down and turned toward me, half of her hair wrapped in tiny tissue paper and pink foam rollers.

"When you were born, the doctors brought me you and said, 'You have a boy.' I didn't have a girl. I want you to start actin' like a boy. You hear me?"

All I knew was something--a defect that Mama, Dusa, and those nappy-headed boys on the playground could clearly see-- made me feel lonely and deeply disliked. Tears streamed.

"What did I do?"

Mama rolled her eyes. "You go 'round here actin' like a woman. Reagan act more like a boy than you. You wanna be a girl?"

The floor blurred through the tears.

"Dusty!"

"Huh?"

"I said you wanna be a girl?"

"No."

"Then start actin' like a boy and folks at school won't be callin' you no f****t. You ain't no f****t. You hear me?"

Liquid fire stirred in my chest and coursed through my body.

"Dusty!"

I wanted to be invisible.

"Dusty!"

Mama's trumpet sputtered sharp, ragged notes that spiraled round and round inside my head.

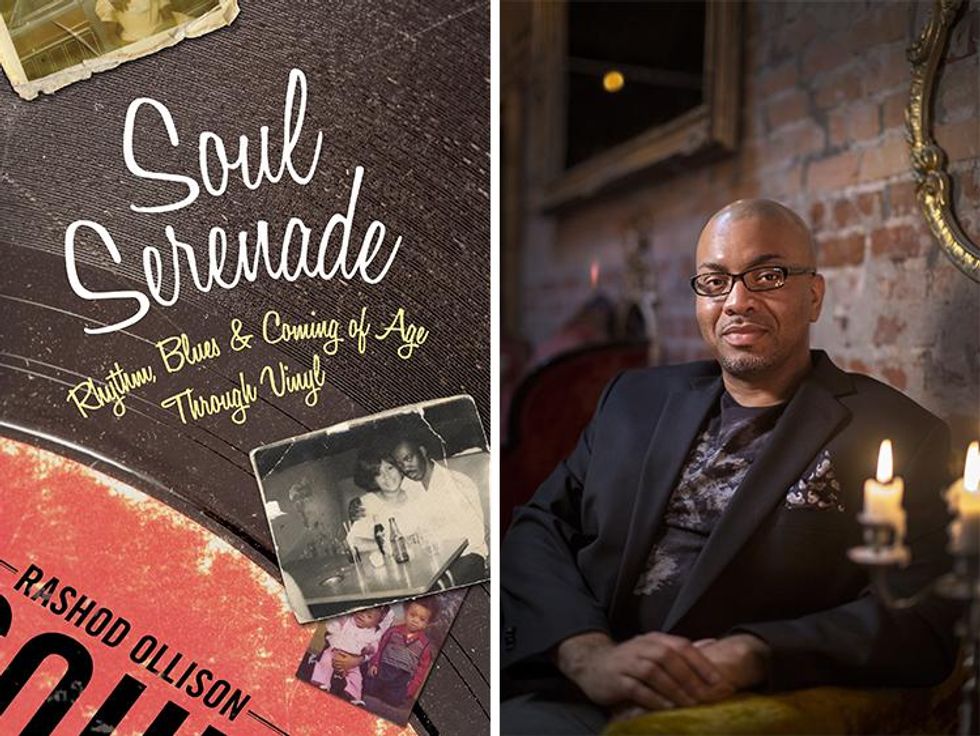

Adapted from Soul Serenade: Rhythm, Blues, & Coming of Age Through Vinyl by Rashod Ollison (Beacon Press, 2016). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes