One of the first works of erotic art I ever saw (when I was way too young to be seeing that stuff) was the George Quaintance rendering of the young man with the giant grapes. That I found it in my father's handkerchief drawer is another story entirely. I mean, who uses handkerchiefs anymore?

Seeing that beautifully rendered work certainly inspired me to create my own erotic art, much to the chagrin of my parents. But I have loved and romanticized Quaintance and his art-driven life for as long as I can remember.

Ken Furtado and John Waybright's Quaintance: The Short Life of an American Art Pioneer lovingly paints a detailed portrait of a forward-thinking creator who died too young (1957) to realize the cultural impact of his heavenly artwork. For his paintings are heavenly in that they inspire one to breathtaking heights, and they transport you to a utopian man-on-man dream world of slippery muscles and sly grins.

Below and on the following pages the authors have granted us rights to publish an excerpt from their ebook, available on Smashwords, that describes Quaintance's life and work in Arizona. -- Christopher Harrity

Chapter 6: Rancho Siesta

Rancho Siesta was many things. It was the name of the Arizona studio where George Quaintance lived and worked. It was an ingenious and overwhelmingly successful marketing concept. And, in the minds and hearts of Quaintance's legions of admirers, it was the closest the American West ever came to an honest-to-goodness incarnation of Xanadu or Shangri La.

The bricks-and-mortar version of Rancho Siesta still exists today, without the magical overlay. It is much the same as it was when George lived there: a medium-sized home in east-central Phoenix, straddling two adjacent lots. It is unusual for the area in that it has two stories and a basement. The property is surrounded by a tall block wall in some places and by cast-iron fencing in others. Decades-old oleanders nearly obscure the view of the building where George Quaintance, Victor Garcia and Tom Syphers once ran the Quaintance Studio. And while there might not have been the six-shooters, cowpokes, livestock, watering troughs and camaraderie depicted in the Rancho Siesta of Quaintance's advertisements, photo sets and canvases, there was surely a steady and heady parade of beefcake in the many models that George painted and Victor photographed.

Above: Montage of a few of the man snapshots Quaintance saved, showing him in various dance costumes and poses.

Above: Montage of a few of the man snapshots Quaintance saved, showing him in various dance costumes and poses.

After renting the home for a couple of years, Quaintance purchased it outright from its previous owners in 1953, for a down-payment of ten dollars and a $6,000 mortgage. The second-story balcony on the west side of the home is where George usually worked. Visitors who were privileged to be admitted would always find on his easel the current work-in-progress, even if it was draped. Long-distance lover, Rev. Bob Wood, visiting the household in 1953, wrote to the authors in a 2006 letter that, "When I bought the Crusader, George was working on Rainbow Falls & had a white sheet hung on the stair railing to represent the falls." This balcony is where Quaintance painted the majority of his male physique canvases.

The composition of the Quaintance household was avant-garde from the very start. Of the three and, later, four men who lived there, Tom Syphers loved Rancho Siesta the most. One of Quaintance's scrapbooks shows a formal portrait of Tom. The painting is not dated, but judging from the other portraits in that scrapbook, it was probably completed in the early- to mid-1940s. Tom held a bachelor's degree from the University of Utah and he was a World War II veteran. He was 15 years younger than George. It is not known whether Syphers was a client, a friend or a boyfriend when Quaintance painted him, or whether they subsequently enjoyed anything other than a business relationship. Anecdotal evidence suggests that Syphers -- a blond -- was once a boyfriend, but if this was the case, he was an exception to the rule. Quaintance had an overwhelming preference for Latinos and men of swarthy skin and dark visage. It was Tom who, when he and Victor inherited Rancho Siesta after George's death, could not bear to sell the property and insisted that they spend at least part of each year there. Only after Tom's death in 1964 did Victor finally sell Rancho Siesta and leave Arizona behind.

Victor Garcia was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico in 1913. He came to the United States in 1938 or 1939. Victor was smooth with a dark complexion, slender and muscular, and he quickly found work modeling for Lon (of New York) Hanagan. It is almost certain that Lon introduced Victor to his bosom friend, George, who soon became Victor's lover. That relationship later subsided into friendship -- but a lifelong one -- possibly due to Victor's absence while he served in World War II. After the war, George and Victor established a solid business relationship, when Victor became the principal photographer for the Quaintance Studio. Victor and Tom Syphers subsequently became a couple -- a shift in the domestic balance that suited all three men well. George, in his will, left his entire estate jointly to Victor and Tom.

After the Storm, 1951. 8 x 11 inch reproduction c. 1950s. ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

After the Storm, 1951. 8 x 11 inch reproduction c. 1950s. ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

A fourth member joined the household in 1954, when George fell in love with his frequent model, Edwardo (fondly called Eddie), and invited him to live with them. Edwardo, whose real name is not known, was a young man from Mexico. While their relationship lasted, George lavished many gifts of clothing and Native American jewelry on Edwardo. For publicity purposes, George told people Edwardo was an Apache, which he felt was a more glamorous and marketable lineage than Mexican. But Edwardo did not remain part of the household for long; in late 1956 or early 1957 he returned to Mexico, leaving behind all the gifts George had given him. The Reverend Robert Wood, an earlier lover in whom George often confided, claimed that Edwardo married upon his return to Mexico. Wood speculated that Eddie's departure from Rancho Siesta was due to inner conflicts about his sexual orientation. Quaintance was devastated. Wood further speculated that a broken heart may have contributed to George's demise, so soon after Eddie's departure.

It can be concluded from the portraits he painted and from his work in Hollywood that Quaintance's first forays to the west coast were in the 1930s. How and when he discovered, and became enchanted by, Arizona is harder to pinpoint. He painted Havasu Creek in the 1940s, but did he actually visit that remote and hard-to-reach spot, and how did he know about it? Quaintance, who was a notoriously poor correspondent and did not keep a journal, does leave a clue, however. In his "autobiography" in the Spring 1956 issue of Grecian Guild Pictorial -- the lengthiest personal disclosure he would ever make -- he discourses about mountains in a way that is both literal and metaphorical:

"My first problem was to get over those high blue mountains I was born behind. After I accomplished that, there were ... many more mountains I had to cross. It seems I have been crossing mountains ever since! The last crossing brought me to Arizona -- a happy place of great space, strength and fundamental beauty. But as I write these lines, I can see great mountains in the distance, and I know that soon I shall be crossing again."

It is difficult to read this passage without believing that Quaintance was foreseeing his own death the following year.

In ads and in marketing materials, Quaintance misleadingly claimed that Rancho Siesta was located in Paradise Valley, an exclusive town located northeast of Phoenix, several miles from the true Quaintance residence and studio. Perhaps "Paradise Valley" had more romantic appeal than "Phoenix." In either case, the actual location of Rancho Siesta was closely guarded. Due to the unconventional nature of the relationships among the residents, George's painting, Victor's photography sessions, and the comings and goings of models who posed unclothed, discretion was a necessity. The physical address of the studio and the telephone number were disclosed only on a need-to-know basis. In a letter Victor wrote in 1976 to the Florida collector who would eventually purchase 22 paintings, he says, "We always had an unlisted phone and you could understand why. We could hardly do any work with people coming over at the time that we had to do the model photography and the sculptures."

Despite the absence of real cowboys and livestock at the Rancho, the casual and abundant nudity -- though never frontal -- of Quaintance's paintings was a reality. Quaintance sketched his models in the nude, Victor photographed them in the nude, and as stated in the previous chapter, at least two sources claim that Quaintance himself painted while nude. In the photographs Quaintance advertised and sold, either the models wore posing straps or they were positioned so that their genitals were concealed. Victor did indeed take photographs showing full frontal nudity, but these were never publicly advertised, being reserved for a private customer list. Surviving examples are both scarce and valuable.

During Quaintance's lifetime, the U.S. Supreme Court had yet to come up with the Miller Test for obscenity, and nearly anyone who was offended by an image could declare it obscene. It was permissible, but daring, to show a man's buttocks, but frontal nudity was a big no-no, as was any suggestion of homoeroticism. Even if a man wore the obligatory posing strap, "excessive genital delineation" -- or even a stray pubic hair -- could be cause for legal trouble. The Postmaster General, who was then a member of the President's Cabinet, vigorously pursued and prosecuted anyone who used the U.S. mail to send images displaying frontal male nudity. Courts of the day still adjudged penises to be obscene. One of Quaintance's former neighbors wrote that "GQ would never sell the full nude photos b/c he was too scared of being arrested, so he would give them away to friends." There is no evidence, however, that Quaintance gave such photos away, and his shrewd business sense argues that he probably did not.

Existing preliminary sketches for Quaintance's paintings, however, show the models without attempting to conceal their genitals. Quaintance would eventually add a censoring flourish in the finished canvases. While he was working, however, he would paint the penises as he would any other detail. Sometimes he or Victor would take a snapshot of the canvas at this intermediate stage. A few of these snapshots exist, but they are extremely scarce. There exist photos of Island Boy before the seagull's interfering wing was painted; of Thunderhead without the cowboy boot masking George Coberly's crotch; and of Morning before the cascading soap suds covered the bather's crotch. Others probably exist.

Above: Full-sized sketch transferred to the canvas for Bacchant.

Above: Full-sized sketch transferred to the canvas for Bacchant.

Among their friends, members of the Quaintance household counted Zaro Rossi and Jim Glasper, who modeled for several paintings each. Quaintance claimed that young Glasper had themost ideally shaped buttocks possible for a man to have. Glasper posed for all four of the foreground figures in Saturday Night. A friend of Quaintance, who lived nearby, reported that Tom, Victor, George and Edwardo "were very quiet and never part of the bar crowd." Even Victor's nephew, who was still a boy in the 1950s, remembers George as being "not terrible sociable." This conflicts with stories of others, such as Rusty Warren, who knew Quaintance at that time. The same friend also claimed that photographs of his own home (whose previous owner was the Maricopa County Sheriff) were later "used for background to some of [George's] paintings -- the Indian rugs on my living room floor match [the ones pictured in After the Hunt]."

When entertaining guests from out-of-town, Quaintance liked to take them to the Stockyards Restaurant. The restaurant still exists, and it still serves food. Now 67 years old, it is the oldest continuously operating restaurant in Arizona. The Stockyards offered perfect local color for a Rancho Siesta experience, being located adjacent to a massive stockyard, where cattle were penned before being shipped off to slaughter, and just north of a meat rendering plant. The aromas must have been powerful! The Rose Room of the Stockyards is flanked by period murals and one is compelled to wonder whether George ever offered to "improve" on them. The Reverend Bob Wood has vivid memories of dining there with George during his visits.

Parr of Arizona (catalog ad pictured at right) was a Phoenix-based business that sold swimwear and "Muscle-Man Gear" to guys who were not afraid to flaunt it. It was started as a mail-order business in 1955, by an enterprising fellow named Ralph Parachek, who needed money for college. His philosophy was "to offer something that can't be found anywhere else." In its heyday, Parr of Arizona had physical stores in Los Angeles, West Hollywood and San Diego. Parr of Arizona advertised in many of the same physique publications as did the Quaintance Studio, even at the same time. Parr and Quaintance were practically neighbors, and they used some of the same models, such as Jim Shoemaker. So it seemed an inevitable assumption that they would at least be on each other's radar. That, however, may never be known. The Parr owners were happy to meet and talk with the authors of this biography, but no one currently employed at Parr had a memory that went back far enough, and the hand-written records of the company's early days were destroyed in a fire. Parachek himself died in 1980, but his company lives on. Today, it calls itself Nu-Parr.

Parr of Arizona (catalog ad pictured at right) was a Phoenix-based business that sold swimwear and "Muscle-Man Gear" to guys who were not afraid to flaunt it. It was started as a mail-order business in 1955, by an enterprising fellow named Ralph Parachek, who needed money for college. His philosophy was "to offer something that can't be found anywhere else." In its heyday, Parr of Arizona had physical stores in Los Angeles, West Hollywood and San Diego. Parr of Arizona advertised in many of the same physique publications as did the Quaintance Studio, even at the same time. Parr and Quaintance were practically neighbors, and they used some of the same models, such as Jim Shoemaker. So it seemed an inevitable assumption that they would at least be on each other's radar. That, however, may never be known. The Parr owners were happy to meet and talk with the authors of this biography, but no one currently employed at Parr had a memory that went back far enough, and the hand-written records of the company's early days were destroyed in a fire. Parachek himself died in 1980, but his company lives on. Today, it calls itself Nu-Parr.

Quaintance continued to travel back and forth between Los Angeles and Phoenix. He augmented his income by painting portraits of Los Angeles matrons and socialites, and sometimes their children. In a 1952 letter to his grandmother, Quaintance mentions that he is still painting portraits. He says of his painting in general, "I love my work. This is what I should have been doing all my life." By the end of 1952, in which year alone he created 14 new male physique canvases, in addition to portrait commissions, Quaintance had produced 30 paintings in his male physique series, but not sold a single one. Yet he could still write, in an April 1953 letter to the Reverend Robert Wood, "Business has grown to fantastic proportions in the last few months and truly I'm practically out of my mind trying to keep up with it."

George wasn't exaggerating. Much of what kept him busy was marketing. Although his paintings -- apart from portrait commissions -- were not in demand, there was a huge demand for other output from the Quaintance Studio. You couldn't pick up a male physique magazine in the 1950s without seeing ads for Quaintance's catalogs, model photo sets, paintings, chromes and sculptures. His mailing list, which was meticulously kept by hand in that pre-computer age, was said to contain more than 20,000 names. Quaintance's business acumen was keen, and he did a brilliant job of exploiting the niche that existed in the consumer marketplace for gay beefcake. He advertised in dozens of physique and muscle periodicals, including some magazines whose lifespan was but one or two issues. He advertised in foreign language publications in Europe and South America, as well. To many of those magazines he offered photographs of his paintings or his models, or feature articles, in trade for advertising.

Above: Quaintance designed 11 covers for Joe Weider's Your Physique, featuring prominent bodybuilders. It is not known what became of the paintings these covers were based on.

Above: Quaintance designed 11 covers for Joe Weider's Your Physique, featuring prominent bodybuilders. It is not known what became of the paintings these covers were based on.

Demand for his work was nearly unquenchable. To the public, Quaintance offered catalogs of his paintings, sculptures and models; black and white photographs, and color slides, of nearly all his paintings; model photographs in several sizes; and several different sculptures, which he called "little figurines." Later, Quaintance offered full-color lithographs of some of his paintings, plus hand-tinted color photographs. After George's death, boxes were discovered containing printer's proofs of color lithographs of every Quaintance painting (except for Noise in the Night, which was mysteriously absent) that had not yet been reproduced in color, so it was apparently his intention to soon offer his fans everything in color.

In the previously mentioned letter to the Reverend Wood, Quaintance wrote that a single issue of Tomorrow's Man, in March, 1953, added almost 5,000 new names to his mailing list, so the success of his marketing strategies was phenomenal. Christopher Clarke, a contemporary of Quaintance, also painted male nudes. Clarke was regarded as the better painter by many at the time. Mentored by Bob Delmonteque, he copied Quaintance's business model down to the last detail. He offered 8x10 black and white photographs of his paintings, greeting cards, cocktail napkins, color slides and compact catalogs. But despite his artistic skill and the erotic quality of his images, Clarke failed to capture the imagination of his public. He did not acquire masses of fans, and he is forgotten today.

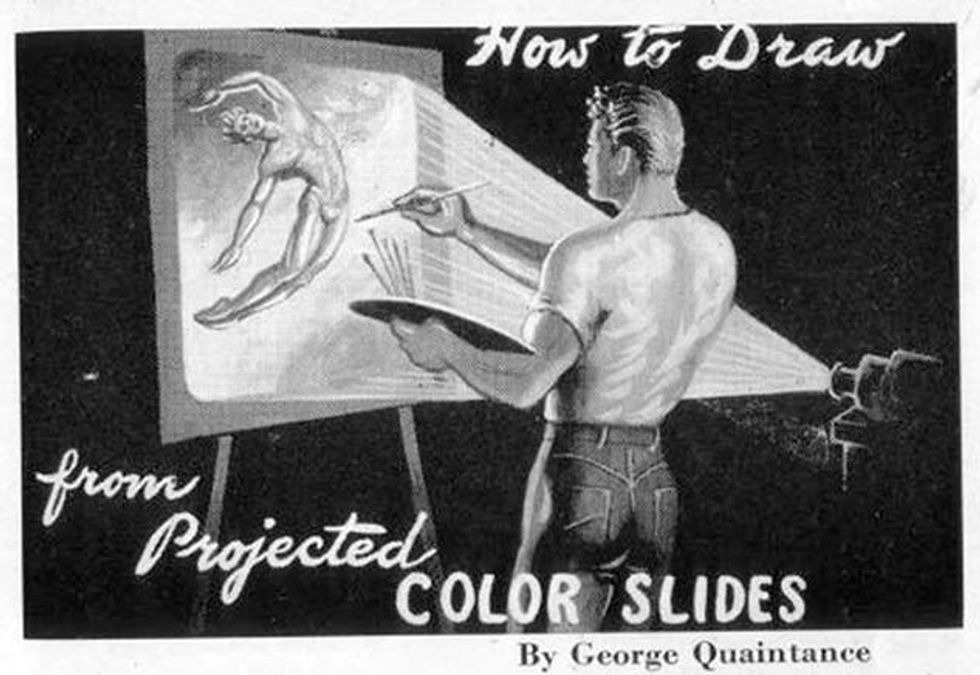

Above: Quaintance explains projection techniques. (Physique Pictorial 2, February 1952)

Above: Quaintance explains projection techniques. (Physique Pictorial 2, February 1952)

Because of George's deteriorating health and constant traveling between Los Angeles and Phoenix, in 1956 he decided to sell Rancho Siesta and move his studio back to California. An ad in the Summer 1957 issue of Physique Pictorial announced, "Quaintance has moved to Hollywood!" His demand as a portrait artist in Hollywood and his close involvement with Bob Mizer in the production of Physique Pictorial made it impractical to leave Los Angeles for long periods of time. George had also developed a heart condition, although he may have been in denial about the seriousness of his cardiac problems, or he may have minimized it to others. He and Victor made offhand references to George's "little seizures," but the Reverend Wood states outright that George had a heart attack in 1956. As a result, Quaintance's doctor put him on a rigid diet. Living in Los Angeles would provide more rapid access to medical treatment, and probably better doctors than Phoenix had to offer at the time.

The decision to move to Los Angeles was accompanied by a shift in Quaintance's artistic vision, as if abandoning Rancho Siesta was an action both literal and metaphorical. Rodeo Victor, painted in 1956, was the final canvas of the Rancho Siesta era: Quaintance's farewell to the West. It was also the smallest canvas Quaintance had painted to date, a mere 22x30 inches. It's tempting to infer that deteriorating health necessitated a switch to smaller canvases that could be completed more easily.

At left: Two Quaintance sculptures Janssen recast in bronze.

At left: Two Quaintance sculptures Janssen recast in bronze.

Quaintance continued to use 22x30-inch canvases for the remainder of his works. His next five canvases, the last of which he did not live to complete, represented a sea change in content. Suddenly he became focused not on cowboys, but on gods and mythology: Zeus, Bacchus, Hercules, and Odin. By mid-1957, Quaintance's ads in the various physique publications began carrying his new Los Angeles mailing address: Box 2236 Terminal Annex. Rancho Siesta was put up for sale, although Tom Syphers says in a letter written to the Reverend Wood, "Our attempts to sell the place have been a little half-hearted, since we refuse to have a For Sale sign on the lawn or have it listed in the papers."

In the final analysis, Quaintance was the "man behind the curtain" of the lavender palace he called Rancho Siesta. Quaintance articulated a vision of his own creation that was unique and original, and that spawned dozens of imitators, copycats, admirers ... and tributes. While paying homage to the glory of Greece and the grandeur of Rome, he at the same time offered a newly idealized concept of ideal male beauty: sleek, sculpted, streamlined and sinewy. Gone was the bulky massive musculature of bodybuilders like Eugen Sandow that was so prized earlier in the century. The perfect V-shaped torso became the new black of masculinity and pulchritude, thanks to George. In the 1950s, when Sen. Joseph McCarthy's witch hunts for gays and homosexuals dominated politics and made grown men tremble, gay men, young and old, all over the world found in Quaintance's works a validation of themselves. Here they could see the ideal of manhood actualized, regardless of sexual attraction.

Above: Ad in The Advocate, offering to sell Saturday Night. It was purchased by a collector in Los Gatos, Calif., who re-sold it. The present whereabouts are unknown.

Above: Ad in The Advocate, offering to sell Saturday Night. It was purchased by a collector in Los Gatos, Calif., who re-sold it. The present whereabouts are unknown.

The men in his canvases offered both art and aesthetic without ignoring the body and its urges. Quaintance offered idealized male images to a rapt audience that was hungry for them, and he offered these images in a context that was rugged, masculine and romantic, as well as sensuous and erotic. He put Levi's on the map as a garment that was sexy as well as serviceable, thus paving the way for the gay clones of the '70s. In his models and in his paintings, Quaintance used Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans, long before racial or ethnic diversity existed in consumer culture (or in contemporary art). And he did so in a way that was natural and that avoided caricature and stereotype. At a time when cowboys and Indians still dominated the airwaves, he exploited gay America's fascination with the West. To all of the cowboy-loving American boys who had grown into a need for a different kind of role model, Quaintance gave his own queered version of the American West. He created and breathed life into an actual and elaborate context, Rancho Siesta, where anyone who wanted to could vicariously live George's vision.

Above: Rancho Siesta today.

Above: Rancho Siesta today.

Tens of thousands of fans loved the work of George Quaintance because he made them believe that Rancho Siesta was a real place, just like in the paintings, where queer boys could grow up to be loving, queer men and the homophobic real world would never intrude. That was so amazing, so unprecedented. People believed in it. Third saguaro on the left and straight on 'til sundown!

(c) Ken Furtado and John Waybright

Above: Montage of a few of the man snapshots Quaintance saved, showing him in various dance costumes and poses.

Above: Montage of a few of the man snapshots Quaintance saved, showing him in various dance costumes and poses. After the Storm, 1951. 8 x 11 inch reproduction c. 1950s. ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

After the Storm, 1951. 8 x 11 inch reproduction c. 1950s. ONE Archives at the USC Libraries Above: Full-sized sketch transferred to the canvas for Bacchant.

Above: Full-sized sketch transferred to the canvas for Bacchant. Parr of Arizona (catalog ad pictured at right) was a Phoenix-based business that sold swimwear and "Muscle-Man Gear" to guys who were not afraid to flaunt it. It was started as a mail-order business in 1955, by an enterprising fellow named Ralph Parachek, who needed money for college. His philosophy was "to offer something that can't be found anywhere else." In its heyday, Parr of Arizona had physical stores in Los Angeles, West Hollywood and San Diego. Parr of Arizona advertised in many of the same physique publications as did the Quaintance Studio, even at the same time. Parr and Quaintance were practically neighbors, and they used some of the same models, such as Jim Shoemaker. So it seemed an inevitable assumption that they would at least be on each other's radar. That, however, may never be known. The Parr owners were happy to meet and talk with the authors of this biography, but no one currently employed at Parr had a memory that went back far enough, and the hand-written records of the company's early days were destroyed in a fire. Parachek himself died in 1980, but his company lives on. Today, it calls itself Nu-Parr.

Parr of Arizona (catalog ad pictured at right) was a Phoenix-based business that sold swimwear and "Muscle-Man Gear" to guys who were not afraid to flaunt it. It was started as a mail-order business in 1955, by an enterprising fellow named Ralph Parachek, who needed money for college. His philosophy was "to offer something that can't be found anywhere else." In its heyday, Parr of Arizona had physical stores in Los Angeles, West Hollywood and San Diego. Parr of Arizona advertised in many of the same physique publications as did the Quaintance Studio, even at the same time. Parr and Quaintance were practically neighbors, and they used some of the same models, such as Jim Shoemaker. So it seemed an inevitable assumption that they would at least be on each other's radar. That, however, may never be known. The Parr owners were happy to meet and talk with the authors of this biography, but no one currently employed at Parr had a memory that went back far enough, and the hand-written records of the company's early days were destroyed in a fire. Parachek himself died in 1980, but his company lives on. Today, it calls itself Nu-Parr. Above: Quaintance designed 11 covers for Joe Weider's Your Physique, featuring prominent bodybuilders. It is not known what became of the paintings these covers were based on.

Above: Quaintance designed 11 covers for Joe Weider's Your Physique, featuring prominent bodybuilders. It is not known what became of the paintings these covers were based on. Above: Quaintance explains projection techniques. (Physique Pictorial 2, February 1952)

Above: Quaintance explains projection techniques. (Physique Pictorial 2, February 1952) At left: Two Quaintance sculptures Janssen recast in bronze.

At left: Two Quaintance sculptures Janssen recast in bronze. Above: Ad in The Advocate, offering to sell Saturday Night. It was purchased by a collector in Los Gatos, Calif., who re-sold it. The present whereabouts are unknown.

Above: Ad in The Advocate, offering to sell Saturday Night. It was purchased by a collector in Los Gatos, Calif., who re-sold it. The present whereabouts are unknown. Above: Rancho Siesta today.

Above: Rancho Siesta today.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes