I've thought a lot about when the exact point in my childhood was that life became unmanageable. A few months before my 11th birthday, out of the blue, my parents, three siblings, and I had to up and move from New Jersey to South Carolina. My father, it seemed, had gotten in too deep with a small-time Italian Mafia gang. He had become involved at first to score cocaine for himself and my mother, but the situation progressed to the point that it seemed he needed to leave and take the whole family with him.

Years before and right around the time I was coming to terms with the fact that I was queer, I'd tried to tell him I was really a boy. That first time I'd come out to him as transgender -- even though I didn't know the word for it then -- he'd shut me down, then humiliated me for coming out. I was left in a female body unsure of why I couldn't stop staring at girls and thinking about kissing them. I knew enough by 10 years old not to say anything to my family about this. Plus now my parents, my siblings, my cat, and I were suddenly crammed into a hotel room in Myrtle Beach, S.C.

Before that, I spent my childhood mostly with my mother and my siblings in New Jersey and Florida. I built forts, picked fights, played baseball, and wore a perpetual red Kool-Aid mustache on my upper lip. I was a dirty, tough, sweaty, independent, creative, and smart kid. I was my mom's right-hand man and took care of whatever she needed -- including her at times -- and adored my siblings. We moved about every six months due to financial instability, living in and out of hotels, winter rentals, summer rentals, trailers, and small apartments.

My parents both used drugs and drank daily. My dad hit us, threatened us, and was verbally abusive. He told me I was stupid nearly every day. The first 10 years of my life were traumatic but nonetheless the best years of my childhood. We had a strict curfew, and my siblings and I were not allowed out of our rooms by the time my dad arrived home from work.

But once we arrived in Myrtle Beach I couldn't escape dad's grasp. We alI lived in a tiny room, and I retreated into spending all my time with my cat, OJ. OJ was my only constant at that point, and our connection was deep. As I fell asleep every night, I held my best friend in my arms and bartered with God. I promised God that I would get better grades and stop getting into fights if I could just be made normal.

Then my parents found an apartment for us to move into in the most northern part of Myrtle Beach -- and OJ was gone. Nobody told me where he went. Nobody gave me any forewarning. He just disappeared.

I remember unloading the moving truck and sobbing with the realization that he was gone. I had tears streaming down my face and onto the black trash bags filled with my family's belongings. I rarely cried or showed fear as a child, especially around my dad. And after that day, I would only grieve the loss of OJ alone, late at night, after everyone else fell asleep. I bottled up my hurt and loss. But that afternoon I just couldn't help it.

I knew it wasn't safe to show vulnerability around my father, and I'd learned that young. Like a number of trans men I've met, I found that the mixture of my "female" body and my masculinity brought out a peculiar rage in others. He oppressed me regularly for being assigned female at birth,but also treated me as male by trying to "toughen" me up, perhaps unconsciously recognizing the gender inside me.

As I struggled to hold back my tears over the loss of OJ, my father snapped at me while I put a bag down in the living room. "Stop crying!" he said annoyed. "Grow up. You're acting weak, and crying isn't going to do anything!"

Still in shock and feeling completely hopeless, I looked him in the eyes. "I don't care." I said. He responded by grabbing me by my throat and slamming me into a wall. With one hand he lifted me off the ground.

"Do you want to know what happened to your fucking cat?" he asked. I nodded, feeling myself choke. "I drowned him. I put him in a bag and threw him off the dock. If he went to the Humane Society he was going to die anyway."

A few weeks after that I felt suicidal for the first time. It was my 11th birthday and I was sitting in the backseat of our family's car with my three siblings. My cheeks stung from where my father had just slapped me across the face. He had said something rude to me and I'd stood up for myself. Now I was staring out the window dead-eyed, battling with myself the rest of the ride home. I eventually managed to convince myself not to open the backseat door and roll out of the car. I just couldn't be sure that one of the vehicles behind us would run me over and end my life, as I hoped. I was also devoted to my siblings and their well-being.

For the next five years, my father was around a lot. He progressively became more violent and controlling. Nothing improved, and our living situation only became worse; my brothers followed in my father's abusive footsteps. After a particularly brutal physical assault at 16, I felt my only option was to run away from home.

As a homeless youth, I came to embrace my identity as a queer, and later in life, as a trans man. Today, I live and work in Brooklyn after doing activist organizing for years in North Carolina. I visited my teenage haunts a few weeks ago for my 29th birthday. With my girlfriend sitting beside me on the two-hour drive to the airport, I suddenly felt the rest of the story come spilling out. I'd spared most everyone the details until now.

I talked about working full-time while in eighth grade, the 13-year-old skater boy I secretly dated and had phone sex with in middle school, how I was thrown into lockers and made fun of for being fat in high school, the first girl I fell in love with, the sexual assault I encountered, what South Carolina was really like, how my grandmother used to buy drugs from the people who once threw me into lockers, details of the assault that pushed me to finally run away, how I would snort Xanax and take shots of vodka to start my day when I lived with my parents, the things I did when I ran away from home for survival, when I started using meth my senior year, my art high school that saved my life, the punk house I lived in, the summer I spent in Atlantic City, the first time I felt like a man as an adult, and how I got to Asheville, where I recovered and met her.

Finally sharing it all left me feeling euphoric and relieved. And then I felt a wave of heartbreak -- and I still do when I think of it -- because of all the things my dad taught me that haunt me to this day; that need to push myself to live up to the ideals of "being a man." I also felt angry that ever since I began being perceived as male, I hadn't felt allowed to tell anyone the details of my violent past for fear of taking up too much space. I didn't want to be seen as that kind of man.

After talking to my girlfriend, I felt clear on a lot, but two questions remained. How does my abusive past still affect my relationships? And why did it feel necessary to bury much of my past when I encountered transgender and queer people who guilted me for possessing male privilege, even though I am so much more than that one facet of myself? That second part was one of the biggest surprises I encountered when I finally escaped my awful home life into what I thought was the safe haven of queer and trans spaces. It turns out nobody wants to hear boys cry, just for different reasons.

Every day now I struggle with myself. I can't seem to figure out how to interact with the world because I am a transgender man who grew up in a severely abusive household. Most people are cisgender. Most people aren't the kind of survivor I am. When people see me they only see the fact that I am a white, passing male. They don't see the past that leaves invisible scars. They don't see that I am a man who has done a ton of self-work that has allowed me to transition, stay alive, and be present despite the trauma. They see a confident, funny, and slightly mopey man who presumably has not had to work as hard as they have for anything. Because: privilege.

Truth is, I try to love myself but really have a hard time being sympathetic toward myself. Honestly, I struggle with being a man, knowing what damage men can cause. Growing up in a household where I was abused daily, primarily by men, does not help me in feeling comfortable with or fond of the gender, let alone being a member of it. I struggle too with many men and their inability to recognize their privilege and not make others feel responsible for their insecurities. I know that being so harsh on them will only lead me to holding myself to impossible standards, but it's hard to avoid it.

Meanwhile, many of the loved ones I've gathered in my queer and trans chosen family blatantly hate men and will say so. I find myself surrounded in some activist circles by people who hate me simply for being a man. And I get it, partly: I look like the face of those who have done us the most damage. But they forget that I'm caught in systems of oppression too. That I too could be hurting.

I face transphobia. One of my brothers, for instance, found me on Facebook a few months ago and told me I was not a man. He threw the chromosome explanation in my face. He called me by my birth name and threatened to murder me.

And then there are people I've tried to date. Some of them (usually gay men) have used excessively harsh language to turn me down after finding out that I'm trans. They'll say things like, "You're cute, but I don't like pussy. Just a preference!" I was in a relationship with a woman for two years who never dated a man before and only found it acceptable to date me because of the state of my genitalia.

I sometimes find myself back alone in my room again, crying late at night when everyone else is asleep. I've had to grieve the loss of my past and parts of my body while facing the fresh pain of being "called out" and judged for only the privileged parts of me that others can see. I'm simultaneously being told, overtly and subtly, by family, would-be lovers, other men, the media, and others that I am not a real man. Sometimes all of it feels so reminiscent of how my abusive father treated me. Folks doing the callouts on my gender -- whether they come from the most progressive or conservative arguments -- rarely consider my potential complexities and rarely consider whether their words might trigger abuse survivors.

On the worst days during my transition, I'll admit, I've wanted to kill myself after feeling so trapped, so invisible and generalized, by how other people perceive me: as a white man who is inherently only capable of oppressing others and basking in privilege, or as a "fake" man with a target on his back.

I've continued to have to do a lot of work on myself. I'm working on letting all of this go, not being so susceptible to hurt, and trying to stop being so angry. In general, I am trying to loosen up. In meditation recently I compared my anger to me punching myself in the face but expecting someone else to get a bloody nose. Anger doesn't work. It doesn't make me feel good. It doesn't give me power. It doesn't let my true self shine through. How do I not internalize all of this? How can I stop feeling so isolated? How do I integrate my past with my present while living my life as two different people?

I guess my only answer is to reframe what my true self is and show that to the world. My authentic self is a soft, nurturing man, who also doesn't take any shit. All I can do now is try to tell my story and surround myself with people who see all the parts of me.

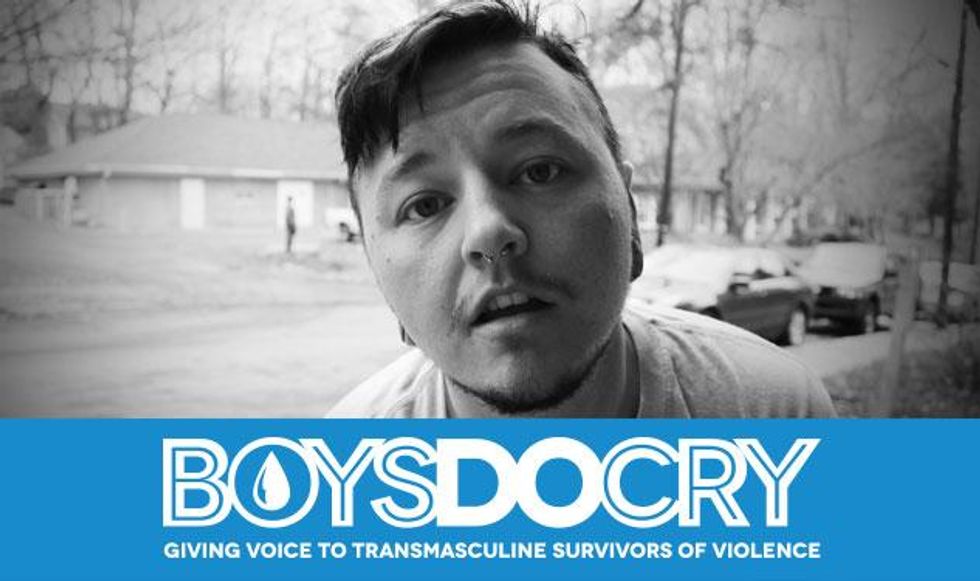

BASIL SOPER is a transgender writer, activist, and Southerner who wears his heart on his sleeve. He wants to write a memoir and continue utilizing intersectional practices while operating in the social justice field. He can be reached at www.ncqueer.com.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.