When Botswana

first offered free AIDS treatment, health authorities in

one of the world's most infected countries braced for a

rush. It didn't come. Most people were still too

afraid to get tested for the deadly scourge.

The startling reluctance to seek help in one of

the few African nations able to provide it prompted a

radical rethinking of how testing is done here. An HIV

test is now offered as a routine part of any medical visit.

In most countries, patients are left to ask for

a test themselves, then put through extensive

counseling to prepare them for the outcome. But

despite decades of education campaigns, World Health

Organization officials estimate that fewer than

10% of HIV-infected people in the African countries at

the epicenter of the pandemic realize they have the

virus that causes AIDS.

Botswana's decision to start routine testing

initially caused alarm among international health

advocates, who worried that patients' rights to

confidentiality and informed consent would be compromised.

"I think the first right of a human being is to be

alive. All other rights are secondary," countered

Segolame Ramotlhwa, operations manager for the

national treatment program dubbed Masa, or New Dawn.

He argued that confidentiality was being

confused with secrecy, making doctors reluctant to

even suggest testing for a disease that has infected

more than a third of Botswana adults. Doctors believe

pulling patients aside for special counseling is

intimidating and helps fuel the stigma that keeps

patients from seeking help.

Howard Moffat, medical superintendent at

Princess Marina Hospital in the capital, Gaborone,

said people who were not sure they wanted to know

their HIV status often emerged from counseling determined

not to be tested. "I think the medical profession

itself...played a major role in creating this fear of

AIDS and this quite irrational reluctance to be

tested," he said.

Since the beginning of 2004, Botswana has

treated HIV tests like any other medical procedure.

Patients have the option to refuse, but doctors say

most don't. They estimate up to 35% of the 1.7 million

population now know their status.

If the test result is HIV-negative, a

health worker will briefly reinforce the importance of

staying that way. If HIV-positive, the patient will

receive help to manage the condition and treatment when

needed. Most people only see a doctor when their symptoms

are severe, by which time it may be too late. It takes

three to four times more resources to save someone who

arrives on a stretcher than someone who is still on

their feet, Ramotlhwa said.

When Kelatlhilwe Segole was pregnant, she was

not offered an HIV test and unwittingly passed the

virus to her daughter, now a 7-year-old. Both are now

on treatment, but her husband refused to be tested until he

was in a wheelchair. "I kept telling him he will die

because of not knowing his status," said the

fragile-looking 27-year-old, as she waited in a

daylong line for her medicine.

Much of the emphasis on voluntary testing and

counseling came from HIV's early association in the

United States with homosexuality, which is widely

taboo in sub-Saharan Africa, home to more than 60% of the

estimated 40 million infected globally. This became the

international standard, even though HIV is now

overwhelmingly a heterosexual disease that killed 2.4

million on this continent last year alone.

Life-prolonging antiretroviral medicines that

have turned HIV into a manageable chronic condition in

wealthier countries remain out of reach for all but a

handful in Africa. They are expensive, and most countries

lack the medical staff and infrastructure to dispense them widely.

Botswana was the first country to offer free

medicines to all who need them in 2002. It now has

half the estimated 110,000 in immediate need on

treatment. Botswana rights activists agree on the urgency of

reaching the other half but worry that many consent to

a test without being prepared. There is a cultural

reluctance to question doctors here.

A study of antenatal clinics in Botswana's

second city, Francistown, found that 90.5% of women

tested for HIV in the first three months of the new

policy, compared with just over 75% in the last four months

of the voluntary approach. Many, however, failed to

return for their results. "At the moment it seems like

a numbers game, a total drive to get people to know

their status. The question is, Then what?" said

Christine Stegling, of the Botswana Network on Ethics, Law,

and HIV/AIDS. "I have a feeling that what is happening

is, health care providers are getting out of

communicating meaningfully with their patients."

The new approach is more likely to reach women,

who are more frequent visitors to health services

because of pregnancies. Men continue to be

underrepresented in Botswana's treatment program. Stegling

believes testing numbers are going up in part because

people are starting to see the effects of treatment.

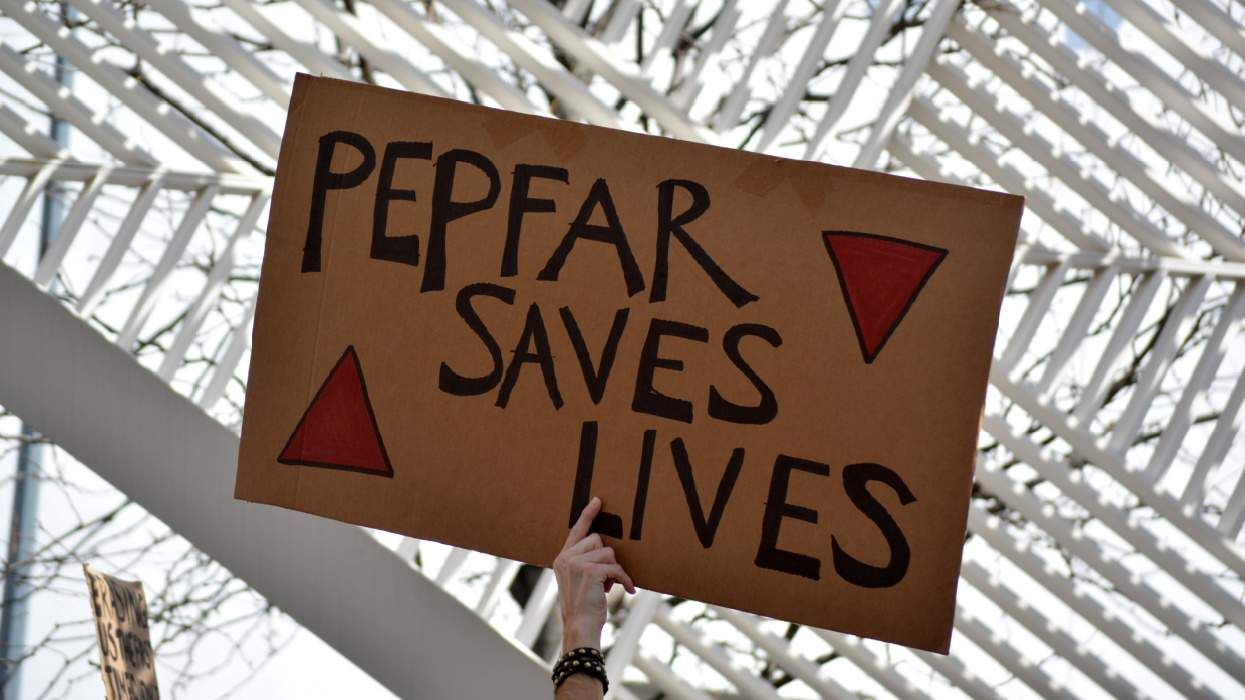

WHO and UNAIDS now encourage routine testing in

all HIV-prevalent areas where antiretrovirals are

available. But for millions, a positive result remains

a death sentence. (AP)

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes