Mark Segal moved to New York City in May of 1969 and a month later found himself at The Stonewall Inn as the now-infamous police raid began. Those around him responded casually. It was a usual occurrence, a wholly unremarkable event right until the moment it wasn't.

"The police came in, pretended that they were doing their duty, got their pay off...the difference here was they barged in, they threw people up against the wall, they extorted money from some of the older people, they harassed the drag queens. It was pretty violent," Segal says. He immediately started organizing with the Gay Liberation Front, returning to Stonewall the next night and the next.

"Everything we did in that first year was basically illegal. And we wouldn't be stopped. We were going to be out, loud, proud, and don't even try to stop us."

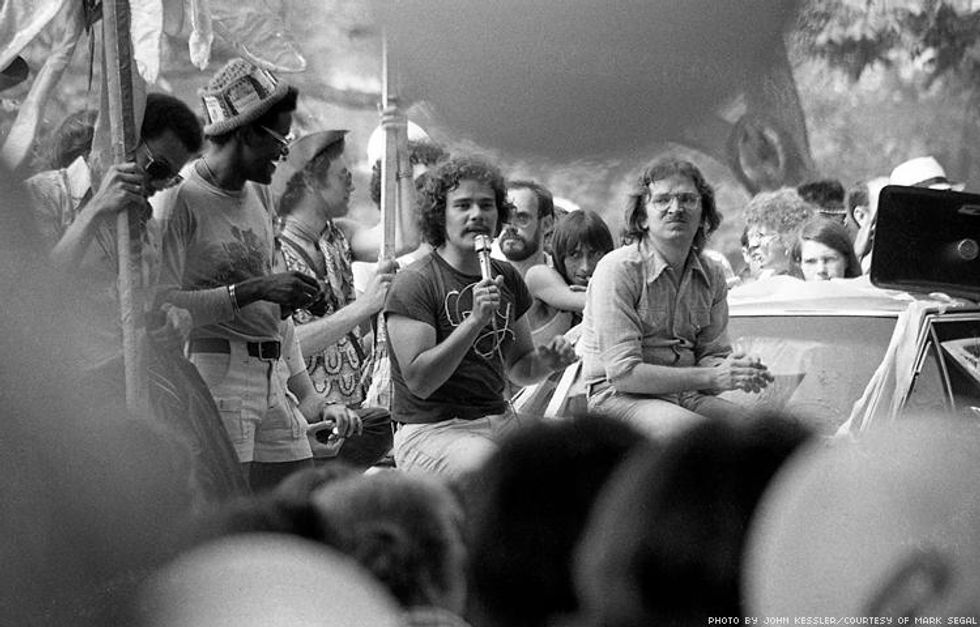

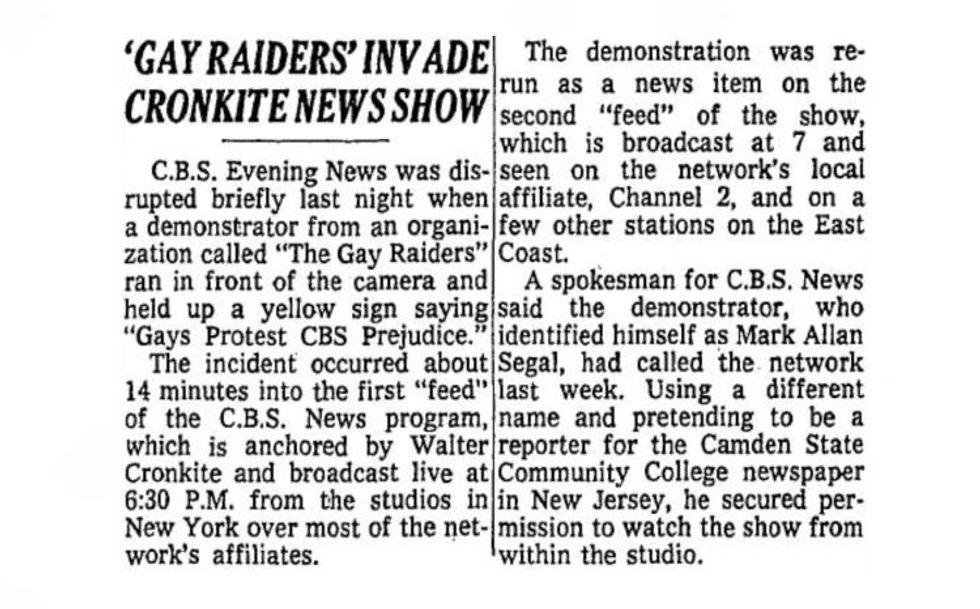

Stonewall sparked Mark Segal's lifelong commitment to activism which included interrupting Walter Cronkite in the middle of delivering the CBS Evening News while waving a banner that read, "Gays Protest CBS Prejudice". On this week's episode of LGBTQ&A, Segal looks back on the last 50 years of fighting for LGBTQ+ people and the special ingredient that underlies all of his activism: humor

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

JM: You moved to New York City in May of 1969. The Stonewall Inn was the first bar you ever went to and a month later, you were there when the uprising began. That's a wild introduction to gay life. Did it feel like that at the time?

MS: It felt like something that I should be doing. As an 18 year old, what you did in those days if you were gay was walk up and down Christopher Street every single night, all night long. You'd meet with your friends and basically hang out. Then sometime during the night you would pop into the Stonewall. So, that was a usual night for me.

The only thing that was different was when the raid began because I had never been in a raid, but the people around me had been. When I asked, "What's going on?" they said, casually, "Oh, just another raid." That struck panic in me because I didn't know what it was.

JM: To them it was just a common occurrence?

MS: It was the usual. The police came in, pretended that they were doing their duty, got their pay off, and left. The difference here was they barged in, they threw people up against the wall, they extorted money from some of the older people, they harassed the drag queens. It was pretty violent.

After being carded and led outside, we began to form a semicircle, somewhere in my head it clicked, "Women are fighting for their rights, Blacks are fighting for their rights, Latinos are fighting for their rights. What about us?" And I swore to myself at that moment that was going to be my life's work.

JM: You wrote that it was not the biggest riot ever, that it's been tremendously blown out of proportion. What specifically has been blown out of proportion?

MS: I think what people don't realize is that most of the action took place on one single block. Aside from that one block, there were little incidents happening up and down Christopher Street, but not very much. It also went on for hours. Nobody was there the entire time. No one knows exactly who was there, because in the middle of a riot you don't take a roll call. There was no first brick thrown because there were no bricks in the area. Were there stones thrown? Were there coins thrown? Cans and bottles? Yes.

JM: In the mythologizing of Stonewall, we talk about how it lasted three days, as if it lasted three days on its own. I hadn't realized that people like you and Marty Robinson were writing on the sidewalk with chalk to tell people to come back to Stonewall the next day. You intentionally kept it going.

MS: Marty Robinson, who was the leader of the action group which I was part of, came up to me with chalk. I'm one of those people who wrote up and down the streets, "Tomorrow night, Stonewall," which created, in a sense, the second night where Marty [Robinson] and Martha Shelley stood and made speeches from the front door of the Stonewall and made the point clear that we were oppressed. We needed to do something. And that meant fight back.

"How many days did Stonewall go on?" For me, it went on 365 days because right from the beginning, we started organizing. That included writing on the street to the third or fourth or fifth night, I don't remember which, where we had leaflets saying, "We're not going to allow the police do oppress us anymore. This is our neighborhood." That's what is so revolutionary. That was, in itself, illegal.

When we gathered at the steps of Stonewall, that was illegal. Homosexuals could not congregate together. That was illegal. When we said we were going to fight the police, that was illegal. Everything we did in that first year was basically illegal. And we wouldn't be stopped. We were going to be out, loud, proud, and don't even try to stop us.

JM: Marty Robinson was one of the co-founders of the Gay Liberation Front, a group that helped forge the foundation of the LGBTQ+ movement and community. Was the Gay Liberation Front created in response to Stonewall or was it already in existence?

MS: There were many organizations before Stonewall. The leading one in New York was Mattachine. And on my first or second week in New York, I tried to go into Mattachine. They said I was too young. As I was leaving, that's where I met Marty Robinson, who was coming out, and he said, "You know, these guys, they don't get it. They don't understand what's going on in 1969. We just can't be doing a once-a-year march. We need to do something more."

He created the action group which I was a member of. There were many little groups around New York. After Stonewall, we all united for the first time. Action groups, fairies, lesbians, we got together. That's what created Gay Liberation Front. It was the first united movement in our country from the grassroots up. Before that, drag queens weren't allowed to be part of it. Street kids like me weren't allowed to be part of any movement. That changed with Gay Liberation Front.

JM: Are you saying that before Stonewall, that lesbians and bisexuals and trans people all felt like we were part of separate communities?

MS: Yes. Oh, Stonewall brought us all together. You've got to remember that any gay movement that existed before us wouldn't allow people to be seen in public without a suit and tie. I was 18. Come on, do you think I was wearing a suit and tie? You had to be orderly. I was anything but orderly. You had to be at least 21. I was 18, and white, which is a secret that we very rarely ever talk about.

JM: Was being white an explicit rule?

MS: No, it wasn't explicit, but if you take a look at the pictures, there was only one black person marching in anything. Now, if you look at various disturbances, riots, whenever this happened in our community...What we got from Stonewall was an everlasting movement that from the ground up was inclusive of everybody. We included everybody and anyone who wanted to be part of our movement.

But they had to understand what we were and how different we were from anything before then. We were not going to be quiet and we were not going to go by society's rules. The first thing we were going to do is self-identify. We were not going to be called homosexuals. Gay became the major word and we refused to be called homosexuals. That's a scientific term. Put it up on a laboratory shelf somewhere. I want to be visible. I've fought for visibility and I will remain visible. I'm a gay man. Get used to it, people.

JM: What were the early goals of the movement back then?

MS: Several things. Number one, identity, saying who we were. Number two, let society know who we were, not the myths that they had about us. Number three, we were going to be out, loud, and proud. That last word is extremely important. We were going to be visible. And if they didn't want to see us, we were going to make them see us. It was a total change.

We also wanted to create a community. Do you realize there was no gay community before that? So, before Stonewall, this is what we had for community. We only had four things. We had cruising areas, the gay organizations who held meetings maybe once a month, private parties, and a few illegal bars. There was no other community. That was it.

On the first month after Stonewall, we were on the streets every single night leafleting, we were having social events which were illegal, we created legal alerts, medical alerts, we had a trans committee, which eventually became Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, we had a gay youth organization, we had hotlines. We created community.

JM: We've named a bunch of groups from the Gay Liberation Front to the Mattachine Society. There's also the Daughters of Bilitis, the Lavender Menace, the Transsexual Menace. Our history is littered with short-lived groups. What is your assessment for why that is and if that is at all unusual for a movement?

MS: I really don't know. What I can say is, it's worked for us. I love Lambda Legal. Lambda Legal, one of the four founders was a member of Gay Liberation Front. You would be amazed at how many things are continuations of Gay Liberation Front. The beginning of GLAAD were disruptions that I did in the 1970s, which changed the network TV programming and news divisions.

JM: How much conversation and dialogue was happening with groups in other cities? Did it feel hyper localized?

MS: When I did the media zaps, for a short period of time I was probably the best-known gay activist in the nation. There was nobody else who had been seen by 60 million people in one shot, which was the CBS Evening News.

The New York Times / December 12, 1973

JM: That's when you interrupted Walter Cronkite live on air.

MS: Oh, yes. At that time, there were only three networks in the country: ABC, NBC, and CBS. One night, I disrupted the CBS Evening News. Walter Cronkite was the most trusted man in America. Many of those 60 million viewers, for the first time, saw a gay person. Gay Liberation Front came into their living room. And I did that on the Today Show, the Tonight Show, and others. That brought me on to the talk show circuit, which hadn't been open before to people like us.

My whole thing was visibility. So, I used that tool to take that. For example, when I did The Phil Donahue Show the first time, I believe it was in Youngstown, Ohio. When I went there, I made sure that the night before, I met with the leadership of the LGBT community there and said, "This is what I'm doing on a national basis. You can be doing this on a local basis." And I did the same thing in Chicago. I did this everywhere I went.

JM: Did you feel famous at the time?

MS: Oh, absolutely. Up to 1969, and this is only three years later, there were only about a hundred gay activists out in the country. You would have 10 to 15 gay organizations in the nation, but they were only in major cities and maybe one or two people in them were out. Think about that now. Up until 1970, the one and only national march drew under 100 people. When I was appearing on TV, it was a big deal. And I was on every talk show you could possibly imagine. And if I wasn't on a TV show, I was disrupting TV shows. And this was making, again, headlines in newspapers

So yeah, I felt that way, and I'm going around the country with holes in my shoes. What I'm still dealing with to this day, and lots of us who were in the early movement deal with this and all say the same line...we would come home and we'd find a gay friend and they would say, "You're ruining it for us," because they were afraid what we were doing would shine a spotlight on them or where they'd go. We were not very popular.

JM: Were they afraid they'd be outed?

MS: Yes. Which was, at that point, 99 percent of our community was in the closet.

JM: You write that being gay back then meant you would live a life of condemnation and unhappiness. That's why so many stayed in the closet. My big question reading your memoir was how did you escape feeling that way? Why did you not believe that, too?

MS: I can't actually pinpoint why. All I could say to you is that when I realized that I was gay and started seeing all the negativity about gay people -- the fag jokes in school or hearing parents or relatives talk about gay people -- the first thing I wondered is, "What is wrong with me?" And somewhere it clicked in me, "There isn't anything wrong with me, but I don't understand why everybody else does."

In order not to embarrass my parents, I moved to New York. So, I was somehow pre-programmed. And I believe that's from the pride that was instilled upon me by my grandmother and my parents because of who I was. I had already felt oppression from about the age of five for being Jewish. I had suffered discrimination my whole life. So, this was just more oppression and I guess I related one to the other.

You do what you can to live, and the best way to deal with that is humor. I was known for that when I did the zaps. At one point, I had handcuffed myself to the city's Christmas tree and when the reporters came and asked, "Mark Segal, you're a homosexual. Why are you handcuffed to this Christmas tree?" And my line to them was, "Because I'm Philadelphia's Christmas fairy." And then I would say, "Now, to get serious. The issues are..."

JM: That is why you were successful, you mixed humor into your disruptions and zaps.

MS: Absolutely.

JM:Do you think humor is missing from the current movement?

MS: Oh, absolutely. It is so drab. It's ridiculous. Drab, serious, angry. We were angry but we had joy in our lives. There's no reason you can't have the two.

JM: You've just turned 70. Are you starting to think about your own mortality?

MS: No. I feel as though I'm in my twenties or thirties. I know I'm old. I know I'm 70. To have the Smithsonian come to you and say, "We would like your papers and artifacts over the last 50 years," whereas the community hated us, all of us, for being activists. That has changed, somewhat. We're now allowed to talk about who we are, what we did. We helped create that safety.

JM: I didn't know if living through the AIDS crisis and having your partner test positive for HIV at one point affected your sense of mortality.

MS: That lover, eventually died of AIDS. During the early crisis of AIDS, he said something to me that I will never forget. I got into a very deep depression and his line to me was, "Get over it. Just because you're not going through it...you can't go through everything this community goes through." The reality is yes, I can. While I'm HIV-negative, I can go through it because I can be a champion for those people who are HIV-positive. And I was during that period of time.

I tried to be a little creative and do some things that nobody else ever did before. I think that's what keeps me going. I continue to do new things. I don't stop. I think if you learn something every day, you don't grow old.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Mark Segal is the author of And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Alok Vaid-Menon, Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Cleve Jones, and Roxane Gay. Episodes come out every Tuesday.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.