One day you're a vivacious college student, flirting with cute girls, worrying about finals, finding a new car on Craigslist, and helping your bestie cope with an unexpected pregnancy. You're happy. Then a repressive new political regime takes power in America and the life you planned for yourself no longer exists as an option. Sounds terrifyingly prescient, right?

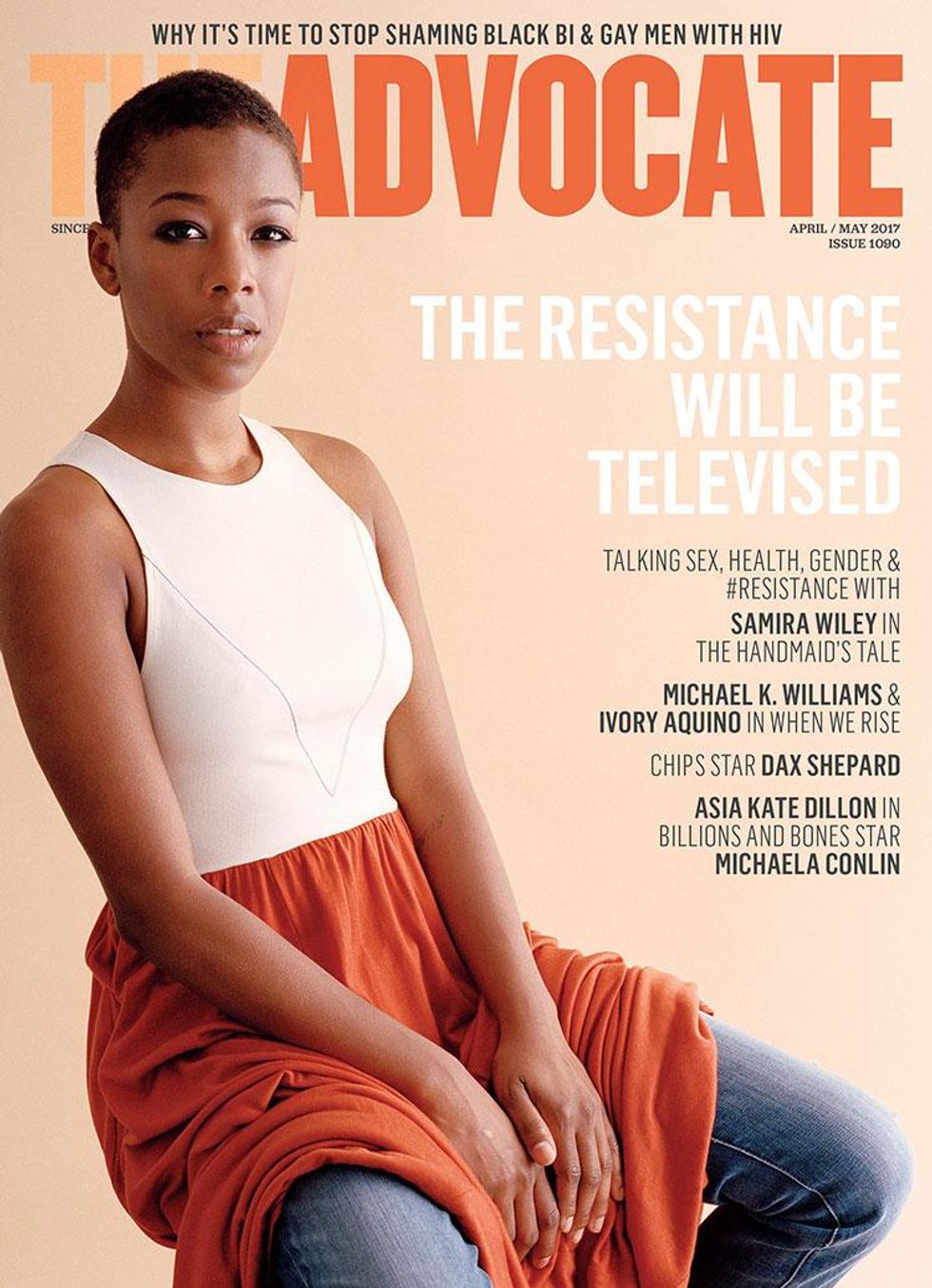

That's what happens to Moira (played by Orange Is the New Black star Samira Wiley) in Hulu's shockingly relevant new original series, The Handmaid's Tale.

Based on the award-winning, best-selling 1980s-era novel by Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale is set in the dystopian world of Gilead, a totalitarian religious society in what was once part of the United States.

June (played by Elisabeth Moss) is one of the few remaining fertile women, so she's enslaved in reproductive and sexual servitude. It's her duty to help repopulate the world. The fundamentalist leaders of Gilead have instituted a caste system in which nearly everyone (except straight cis men) lose, partly as a response to environmental disasters and a plunging birthrate. Except for a few, women are considered the property of the state. Renamed Offred (because her new owner is Fred, so she is Of-Fred), she is separated from her best friend, Moira, a lesbian who is initially sent to be a handmaid as well but may or may not have been killed.

The book was Atwood's response to the Christian right's full-on assault on reproductive rights in the 1980s and the rollback of rights gained by second-wave feminists (sometimes at the hands of other women, like Phyllis Schlafly).

The Handmaid's Tale feels even more prophetic today, especially for LGBT women, feminists, female scientists, atheists, and liberals. I'm not the only one to admit to crying through the first episode.

"I did have some similar feelings to you," Wiley admits of the first episode. "It's a little too real, and it's a little hard to watch." Of course she felt pride, as well, knowing she and her costars -- including Moss, Alexis Bledel, Joseph Fiennes, Yvonne Strahovski, and others -- "were really able to execute what we wanted to. But also a little frightened. It does seem a little too close for comfort."

Created and written by Bruce Miller -- who was joined in executive producer duties by numerous others including The L Word creator Ilene Chaiken -- The Handmaid's Tale couldn't feel more timely.

"When we first started filming we were in the middle of the election," Wiley recalls. "There was a sense of like, Oh gosh, when this comes out we'll really see ... what our country could have been. And then to have the election come to a close in the midst of us filming, you could feel it on set. You could feel that maybe the work that we were doing had a little more weight to it."

In some ways, Atwood's novel has always felt frighteningly possible, which is one reason it has never yet gone out of print. It was previously adapted into a film and an opera, and has spawned countless dissertations. A staple in women's and gender studies programs, the title itself has become shorthand for life in a repressive regime. Young women tattoo themselves with quotes from the book, notably, "Nolite te bastardes carborundorum." ("Don't let the bastards grind you down.")

When Harold Pinter was writing the screenplay for the 1990 film adaptation, he reportedly sparred with star Natasha Richardson over the use of voice-over (Pinter hated it; Richardson demanded it).

Pinter would hate Hulu's new adaptation, because so much of Offred's experience is told via her inner dialogue through voice-over. It's through Offred that we learn bits and pieces of Moira's story too. But Moira's a woman who needs no voice-over, because she refuses to be silenced.

Elisabeth Moss as Offred

"I do think that Moira keeps her voice through[out]," Wiley says. "I think that we all have traits that are sort of just who we are, and that's definitely the kind of person that she is. I think that ... the memory and the friendship between June/Offred and Moira really bolsters Offred in some of the moments where she is losing her touch, or losing the gumption ... ultimately to survive."

After the first episode viewers see Moira in flashbacks, not knowing if she's dead or alive but, Wiley says, "even through the darkest of times; somehow she ... keeps her moral compass in the fight. She really truly believes that she can get through this."

It is, Wiley says, "sometimes miraculous," the way in which Moira sees the world around her becoming a terrifying theocracy, more intolerable than imaginable, and yet still finds "it is her responsibility as a human being and as a woman to always stand up for what she believes in. She reminds me of a ... woman like Joan of Arc who to the end, you know, just would not break. That's the kind of person I feel like Moira is, just at her core."

The series comes just as leading political figures (especially those in the White House) have begun eagerly rolling back women's access to sexual health information, contraception, abortions, and more; while also heightening access to discredited therapies aimed at "curing" lesbians like Moira and Wiley (and other bi, trans, and gay folks).

Coming out at this moment, The Handmaid's Tale feels a bit like part of the resistance movement, in the form of art.

"Even though it's art -- a television show -- art can really... [inspire] real change in people," Wiley argues. "And I felt like we had a sense of responsibility to be able to bring real truth to this, and show it to the world."

Through a series of artful flashbacks, the show, explores how an autocracy, theocracy, or totalitarianism could "sort of just creep up on you, little teeny things happen and you think, well ... this could never happen -- and then it does," Wiley explains. "And then, this could never happen, and then that does."

Wiley considers herself part of the resistance and says she doesn't worry about a downside.

"Artists are in the public eye ... and I think that there is a responsibility when you are being thrust into the public eye," she says. "I think you can really spring forth change, or at least spring forth people thinking in a different way. I'm a big, big, big believer [that] being aware is the first step of anything. We can't move forward if we don't have any awareness of what is going on in the world around us."

Wiley believes artists have a responsibility, "whether that's through standing in front of a big crowd" or making "art that can change people. In my career, I want to be able to work with ... writers and fellow actors and directors and producers that have that same kind of mindset -- that we are doing this not just to do this, but because we have to, because the world demands it right now."

And for her, that means being a role model for young people, especially those who are LGBT. "It is an enormous amount of responsibility that I don't take lightly," she adds, saying that even with the intense media scrutiny around OITNB, she still hasn't tired of it. "I have not been doing this for decades, as some people have. But I don't feel tired. I feel honored, I really do. I feel honored to be in the position that I am."

On the set of The Handmaid's Tale, Wiley isn't the only person playing a queer character, but Moira sets a tone early in the series. She reminds us that the widespread acceptance Moira, June, and their multicultural friends felt in their melting-pot world doesn't always lead to greater advances.

Handmaids attend a rather terrifying ceremony.

As history has shown us, sometimes backlashes can lead a country down a dangerous path. In the first episode of Handmaid's Tale, we see bodies hanging from the city's walls, and learn men suffer too in Gilead: death penalty punishments are meted out for gay men and certain doctors.

In a short span of time, Moira's queer rights are gone and she's being punished for deviance. I ask Wiley if she can imagine what that experience would be like.

"Especially in the post-Trump world, I've had some real moments of panic," she admits. "And I'm trying to quell that and keep that down because I don't think that helps anything. I don't think panic helps anything. I have been able to imagine what that would be like."

For Wiley, it's a new experience. "It's not something I've ever really thought of before, especially since we've had a president who made legal gay marriage equal throughout our entire country. I will never forget that, and I remember the White House being lit up in rainbow colors."

It's disturbing how quickly things can change. "Living in a world -- you know, just a few months ago -- where I felt nothing but love, nothing but acceptance from the majority of the people who were living around me, and only recently have I started to imagine what that might be like ... being persecuted literally for who you are as a person. Of course, there are a lot of people who believe that this is a choice. I think it's not a choice, but I do think that there is a choice to live it openly and honestly. And that is what I strive to do every day. And if that is taken away, you know, it's, it's --" Wiley struggles for the words. "I don't know. It's hard to imagine, but recently my mind has slipped into those dark places."

The actress shares a wonderful theory about the protest that have sprung up around the nation -- and sometimes around the globe -- in opposition to Trump's policies.

"Someone explained it to me recently -- in a way that really rang true for me -- that people now are sort of like white blood cells. This spontaneous thing ... where everyone's going to LAX, everyone's going to JFK, just because we're hurting there. The people are like white blood cells," she says, rushing to the nation's body to defend our system from attack.

That women are leading the charge in these protests from Standing Rock to D.C. is heartening too. In The Handmaid's Tale, Atwood wrote about a hierarchy in Gilead that offers a false sense of power to some women (the Stepford wives of powerful men). It was her nod to the way women are often pitted against each other in our culture. Wiley has seen this in action.

"To be honest, I don't know where it comes from," she admits. "One of the questions that I would get all of the time when I was on Orange Is the New Black since it's such a women-heavy show, we would always get questions [like] 'Is there cattiness on set? And did the women fight each other?' Well, number one, it wasn't like that, but number two, why is that the question that we're getting? That has become the stereotype of women being together ... that if you ever have a bunch of women together, there's going to be [catfights]."

The actress says Moira would have been front and center at those early protests, shutting down airports ("She would have been, absolutely; Samira was at the SAG awards," Wiley laughs). But she does see commonalities between her character and her own life, noting that she can be "very stubborn" and "I do have a real sense of what I believe is right and what I believe is wrong. And I want to be able to ... stand up for the things that I really believe in and have a voice. Moira is never standing idly by. She is in the midst of the protest. She's talking for the little people, she's talking for everyone... who [has] been forgotten, people who just don't have a voice. I think that more than what we have in common -- other than how stubborn we are -- I really aspire to some of the traits of Moira."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.