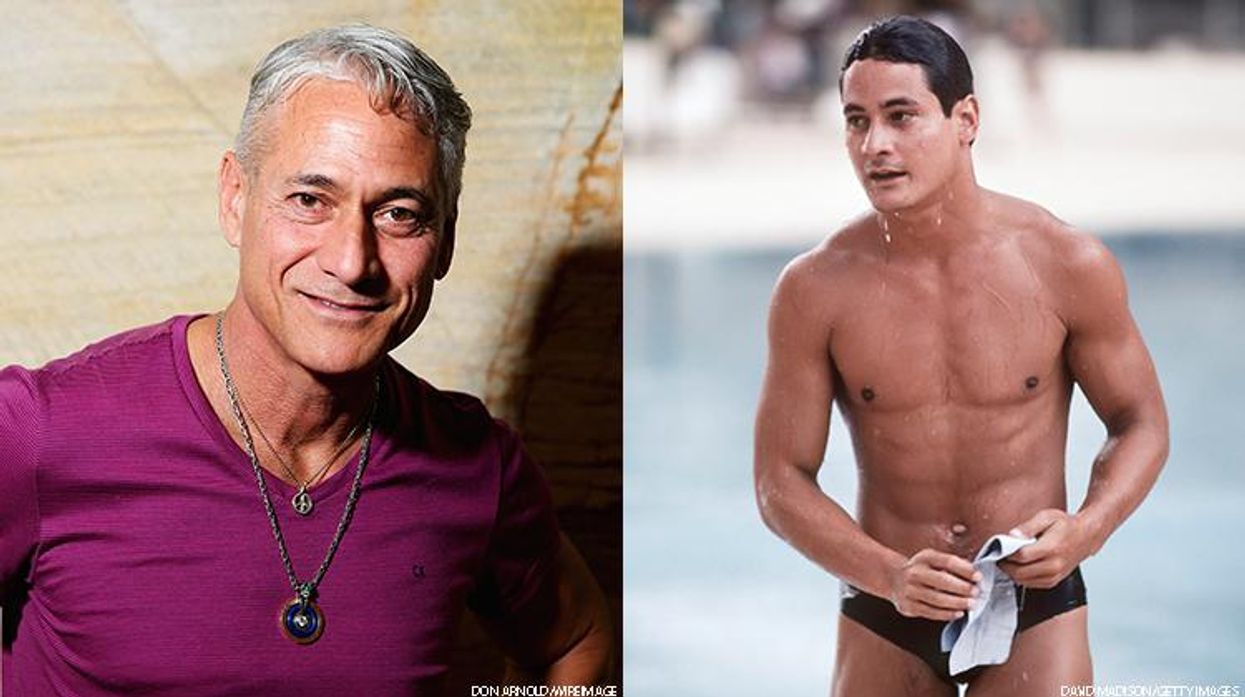

The next time you think about what HIV looks like, think about Greg Louganis winning two Gold medals at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul.

He became the first man and only the second diver in Olympic history to sweep both diving events in two consecutive Olympics--and he did it six months after learning that he was living with HIV. Louganis was taking AZT at the time, setting his alarm for every four hours, even waking up in the middle of the night during the competition to take the medication.

"When I was in the pool, when I was competing, when I was training, HIV and AIDS didn't exist. That was a sanctuary for me. So it was a place that I could go to, really to seek refuge from the stress of the HIV diagnosis," Louganis says. Now at 62, Louganis is proof of what is possible: you can live and compete at the highest levels with HIV. You can win gold medals and be considered one of the greatest divers in the history of the sport.

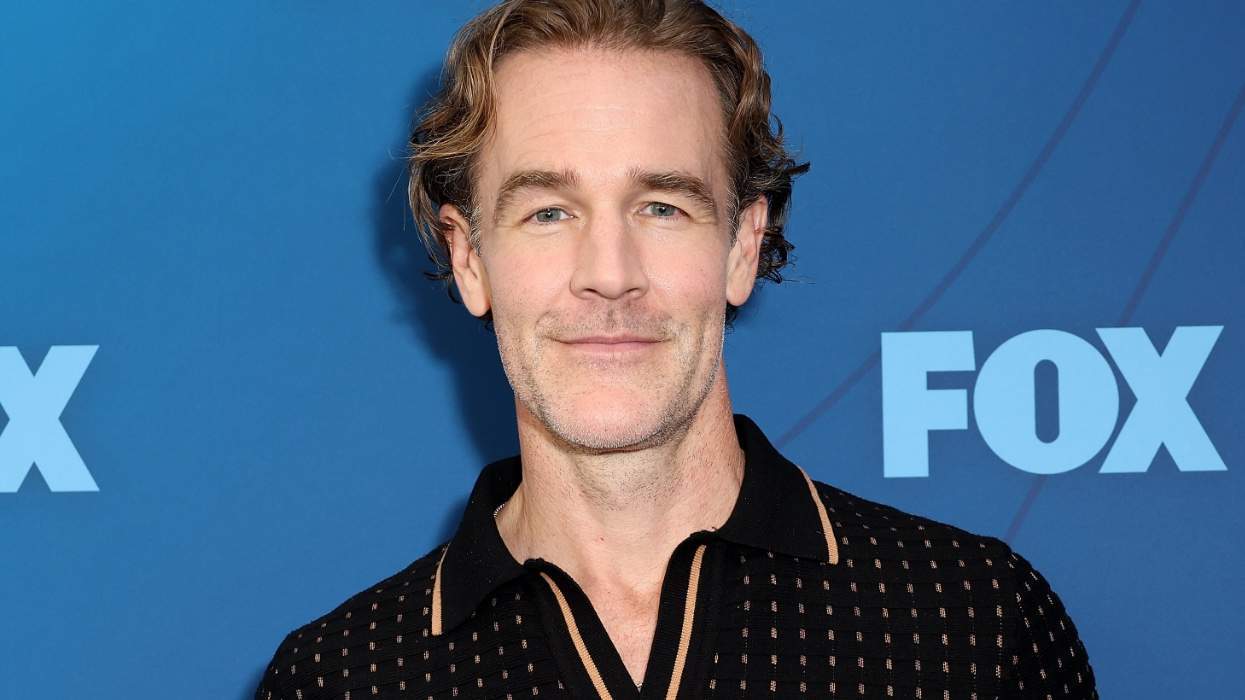

Greg Louganis joins the LGBTQ&A podcast this week to look back on the controversy created by the concussion he received at the 1988 Olympics, sharing his HIV status with the world in 1995, and adjusting to the reality of HIV today, where with access to appropriate treatments, HIV is no longer a death sentence.

You can listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts and read excerpts below.

JM: How were you thinking about HIV and how it might affect your diving career back in '88 when you first received your diagnosis?

GL: I really didn't know. Now back in '88, we thought of HIV/AIDS as a death sentence. So my thought was, "Well, if I'm HIV positive, I don't want to waste my coach's time. I don't want to waste my teammates' time." So I was going to pack up my bags and go back to California and lock myself in my house and wait to die. Because that was what we thought of HIV at that time.

But my doctor, who was also my cousin, he encouraged me to stay and train. He said that that was the healthiest thing I could probably do for myself. They put me on AZT right away because they wanted to treat me very aggressively. Also, at that time there were travel bans, so nobody could know about my HIV status or I wouldn't have been allowed into the country, into Korea. So it was a well kept secret.

JM: This was well before the drugs got good, well before we learned how to appropriately treat HIV.

GL: It's before we knew anything. AZT was an experimental drug. It was initially a cancer drug, and so they didn't know the toxicity. They didn't know potential side effects. We were basically guinea pigs.

The way that it was prescribed back then, it was two pills every four hours around the clock. So you're getting up in the middle of the night, in the middle of the morning, no matter where you are. If I was training, my little alarm would go off, and it's like, "Oh, AZT break." Just like in Rent.

As a performer, it's like, okay, you sprained your ankle? Wrap it up and get back out there. As soon as the music starts, you've got to perform. It's that mentality. I was able to compartmentalize my life. When I was in the pool, when I was competing, when I was training, HIV/AIDS didn't exist. That was a sanctuary for me. So it was a place that I could go to, really to seek refuge from the stress of the HIV diagnosis.

JM: It was at the '88 Olympics when you hit your head on the diving board and got a conussion. You got stitches and then got back up on the board 30 minutes later. I had wondered how much of getting back up there was your drive and determination, versus you thinking you had a death sentence and had nothing to lose.

GL: Well, trying to roll everything up in one little moment, going into the 1988 Olympic Games, I was the odds-on favorite. Going into the competition when I did my reverse two and a half pike and hit my head on the board, in that split second I became the underdog. And so the underdog position is much more comfortable to be in because then you have nothing to lose.

It was a wake-up call to my coach, Ron O'Brien, and myself to pay attention because nothing is guaranteed. Anything can happen, and so it really forced us to focus in on, Okay, let's just do one dive at a time and not get ahead of ourselves. Because once I hit my head on the springboard, I had no idea if I was going to be strong enough to do my dives on the 10-meter platform. I had to just get through that competition on the three-meter springboard first, and then we could look at the other stuff later. And so it really pushed us to focus on the moment, being in the moment.

JM: When you shared with the world that you were living with HIV in 1995, there was a controversy because in 1988, your head was bleeding while you were in the pool, even though there is no way to transmit HIV through pool water. Did any of the coverage focus on you competing with HIV and winning two gold medals? It seems like a big, very public opportunity to help combat HIV stigma?

GL: I guess it kind of turned into that. That wasn't my intent. I was doing Jeffrey, the play by Paul Rudnick. And I played Darius, so I was able to live out my fantasies and fears on stage because Darius is out and proud. He also, I felt, delivers the most poignant message to the lead character, Jeffrey, when he turns to Jeffrey and says, "Jeffrey, hate AIDS, not life." And that was a big part of it because I did. I felt isolated. I felt alone. And I was thinking, you know what? Chances are I'm not the only one. So if I come forward with what I've been dealing with, with my HIV, with all of that stuff and open that door up, then I would hopefully be letting people in who may be feeling the same way to let them know that they're not alone.

JM: You were one of the most famous gay men in the U.S. for a period of time. What has that been like for that to recede?

GL: Okay, so I'm dyslexic. And so I'm not one to...it was never a habit of mine to pick up a newspaper and read it every day. During my diving career, one thing that my mother used to do when I was growing up is she would come in and read the articles, and she'd share with me a nice article that somebody wrote, had nice things to say. And her instructions to me were, "Okay, next time you see this individual," because the sports reporters, we'd see them. So the next time I saw them, I could say, "Thank you for the kind words," so I can be in gratitude and be appreciative of what they might be saying about me if it was positive. The other stuff I didn't really care about, I didn't focus on. It wasn't interesting to me.

JM: You were in a long-term relationship during the peak of your fame. Does any part of you wish that you could have been single and slutty?

GL: It's funny because I probably describe myself more as a serial monogamist. I latch onto somebody, and it's like, Oh, that's it. This is it. This is it. And then I stay too long. And it's like, Oh my God. This isn't working. Oh, this is not what I thought it was. But you learn through relationships and all that.

I'm happily divorced and I'm very good friends with my ex-husband, and we still share a lot of things together. It's a good thing. I think we recognized that it was good for when it was and it wasn't necessarily meant to be a forever thing. But now I'm single, and we'll see. I'm learning I need to be comfortable with myself. And I am. Me and the dogs, we do great. We navigate very well together. And also I'm learning that we don't have to look outside of ourselves for validation, that we can be the validating cheerleader for ourselves and have confidence in that.

JM: You've been very open about challenges with money, post-Olympics. How are you doing today?

GL: I'd be lying if I said, "Oh, it's great. It's great. It's wonderful." No. It's a struggle.

I think everybody's had a struggle with the whole pandemic and the shifting because most of my livelihood has been speaking and that kind of events dried up. It's changed a lot. Have I found my pot of gold? Not yet. Still looking.

JM: Growing up, you were dyslexic and thought you were dumb because of that. You've also said that you thought you were ugly and didn't fit in. And then the world gets to know this handsome, shirtless, Olympic gold medal-winner. Did your brain ever make that adjustment and catch up to the way that everyone else sees you?

GL: No. No. I don't see myself that way. Yeah. I never saw myself in that light. I mean, when they would give me these labels, it's like, Oh, that's interesting. Yeah. I still probably saw this little kid with a wide, ethnic nose.

JM: After the 1988 Olympics, you retired. What's it been like to have to figure out what you wanted to do next?

GL: Well, I didn't think I'd see 30, honestly. Because I was diagnosed in '88 and generally they gave you two years, and so I didn't think I would see 30.

There was a point there, it's like, Oh, I'll do whatever I want because I'm not going to be here. And then a year would go by, a year would go by, a year would go by, kind of thing. So now at 62, it's like, Wow. Now, what do I do? I've got to get a job.

JM: You've seen firsthand the evolution of HIV/AIDS meds. What was that moment like when you found out that with the current treatment you were undetectable and could no longer transmit the virus yourself?

GL: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. That was huge. When that information hit, it was like, Oh, wow. It's like, Okay, this is definitely not what it used to be. But I still go to a couple of doctor's appointments, young men who recently serial converted because it's still frightening. You don't know what it is, what it looks like, and how it's going to be managed and all that stuff. And I've probably been on just about every HIV/AIDS medication that's out there, so I know side effects and all that stuff.

JM: Did learning that you were undetectable have a noticeable effect on your mentality, how you thought about HIV and went up about your life?

GL: No, because what I was conditioned to in my early diagnosis, I'd go to my doctor's appointment, get my numbers, and then they'd put that file back in the shelves, back in the filing cabinet. And that's where I would put it, because Okay, I have my marching orders. I've got to do this, this, this and take care of myself and then go about the business of living. So I really didn't focus on it all that much. I didn't know if there were more medications coming down the pipeline. I wasn't really that stressed over all of that stuff because I knew that it was going to be what it was going to be. I didn't have control over it. A lot of my friends were like, Oh my God. This is the last combination I can do because I'm resistant to all of these drugs. And I just didn't focus on that. When they put the file away, I put the file away.

Click here to listen to the full interview with Greg Louganis.

This is part of LGBTQ&A's new LGBTQ+ Elders Project. Click here to listen to an interview with the 87-year-old trans elder Barbara Satin.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Brandi Carlile, Billie Jean King, and Roxane Gay.

New episodes come out every Tuesday.