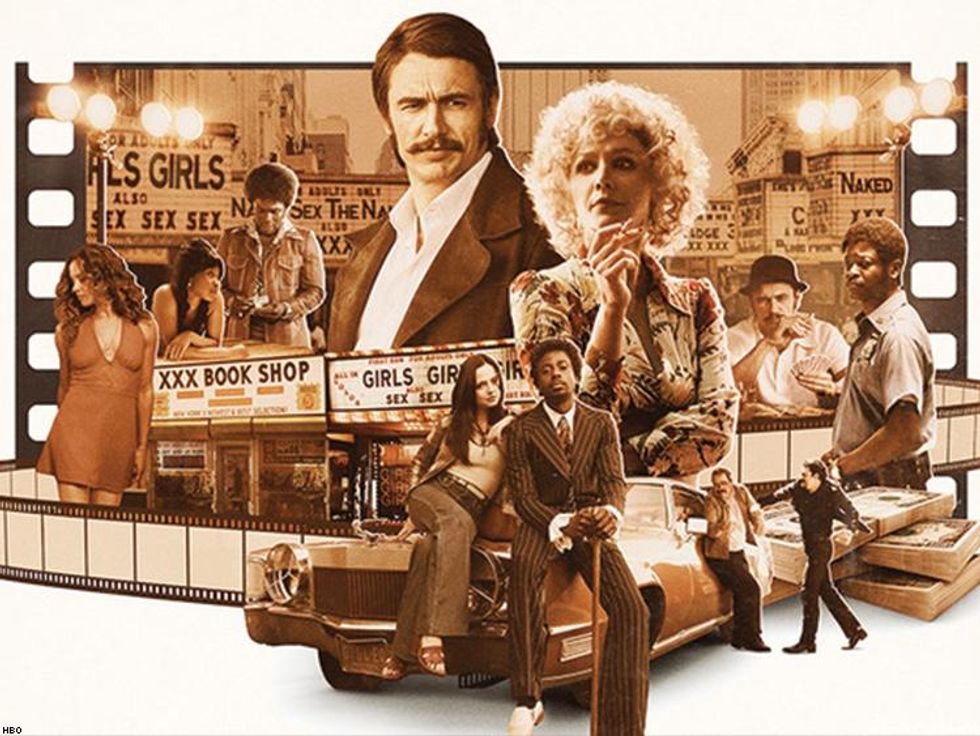

HBO's latest gripping drama, The Deuce, which chronicles the beginning of the legalized porn industry, begins each episode with a montage of '70s New York recorded on 35mm film interspersed with modern cuts. The scene is set to a track from soul legend Curtis Mayfield with lyrics that still ring poignant.

Mayfield sings, "Sisters, brothers and the whities, blacks and the crackers, police and their backers," as the camera dances between each of the montage's subjects. "They're all political actors."

Men visit peep shows, outlaws in muscle cars bribe police officers as they cuff potential clients soliciting sex workers. Fellows in fancy suits and glittering watches test their luck at a red, felt-lined poker table; a dancer undulates her torso, red nails punctuating a black bodice. A tripod steadies its camera on bare legs dominating the frame.

"But they don't know, there can be no show," Mayfield continues. "And if there's hell below, we're all gonna go." Aware or not, viewers are thrown a question.

When the only place left to go is hell, when the powers that be deem a group of people unworthy of equal treatment and protection under the law... What happens then? The answer, as portrayed in The Deuce, is the banding together of marginalized communities for warmth, protection, and ultimately survival.

These relationships form in a range of circumstances. For women sex workers in The Deuce, until the production, distribution, sale and ownership of pornography became legal -- thereby selectively extending legality to those already partaking in sex work -- the law forced those in the business to either bribe the police and pair up with a pimp or risk the streets working solo. The choice then came down to a somewhat possessive partnership with a man who reserved the right to trim sex workers' earnings as he saw fit, or going 42nd Street alone. Nightly. In New York City. As depicted in the show, sex workers were frequently abused by their clients and pimps, blurring the lines between protector, customer, and owner.

Remarkably, amid the turmoil of unregulated sex work, The Deuce manages to weave a semblance of community and interdependence among its assemblage of marginalized characters. Lori's (Emily Meade) pimp, C.C. (Gary Carr), seems to have an honest care for her well-being at times. Despite his violent means of incentivizing Ashley (Jamie Neumann) in episode one--a straight razor dragged across her underarm after she begs not to work during intense rainfall--he keeps close watch over her ever since he picks her out of the crowd at Port Authority Bus Terminal. Although Lori proves capable of navigating the danger of the Deuce by herself, in a vital moment C.C. wields his street smarts to discern the average John from Jack the Ripper and saves Lori from abduction by a potential client.

Murky bloodstains still creeping their way through fibers of the would-be abductor's shirt, C.C. opens the gym bag in the back of the abductor's car, revealing rope, gags and a crowbar: all the unsightly trappings of the end for Lori.

Even if women of The Deuce choose pimps as their primary means of protection, they look out for each other as often -- if not more often -- than their pimps. Each woman on the street (save Ashley, who has grown rather tired of the whole ordeal) has her sisters on her radar whenever possible, informing others of possible danger whenever it may arise.

And within this sisterhood, love blooms. Barbara (Kayla Foster) and Melissa (Olivia Luccardi), both girls of Larry Brown (Gbenga Akinnagbe), find respite from the seemingly mechanical, sometimes dangerous, always consumer-driven sex of the trade with a romance of their own, kindled in secret and kept private at all costs. One of the first moments of authentic, non-commercial sexuality in the show indeed comes from two women, risking their physical safety by being late back to their pimp in order to satisfy themselves on their own terms -- a vital moment of sexual reclamation.

When Barbara is locked up for running narcotics at Larry's behest, Melissa is visibly torn. That safe, reparative, human space is taken from her. Without her partner in crime, who had been conning Johns out of escape money for the two, Melissa's eyes betray her calloused exterior. She seethes desolation.

Melissa and Barbara aren't the only LGBT characters inclusively depicted in the show. Paul Hendrickson (Chris Coy) is a gay bartender who has served queer communities slowly emerging from underground in post-Stonewall New York since before the riots. A veteran of Stonewall itself, Coy's character is the viewer's window into an inclusive, queer historical narrative.

As we're introduced to Hendrickson, he's cleaning glasses during the perennial downtime of a dying gay bar named Penny Lane. Vincent Martino (James Franco) is shown in by mobsters Rudy Pipilo (Michael Rispoli) and Tommy Longo (Daniel Sauli) -- reassuring him, "C'mon, Vince. They don't bite," and nonchalantly normalizing the nature of the bar, "It's a good song." Once the trio are inside and acquainted with Hendrickson, he explains to Martino that his patrons have been threatened with exposure over the telephone at work and home by mysterious, malicious voices looking to choke out the few safe spaces available to queer people. Hence the empty joint.

Taken under Martino's wing and treated to renovations, Hendrickson's workplace booms as a business while remaining a safe space for queer city life. With Martino's procured brawn -- Big Mike (Mustafa Shakir), a hulking black frame with both artistic and safeguarding talents -- transgender, lesbian, gay and bisexual bar-goers are given reassurance that their presence is welcome.

Later in the show, after discussing recent changes surrounding the gay liberation movement (and after Hendrickson corrects Martino on the preferred pronoun of a transgender customer) the two toast to new beginnings on the steps of the thriving bar: a symbol of Martino's willingness to put himself and his business on the line as allies to queer communities.

And true to his word, Martino's bar serves as a sort of hub for the rest of The Deuce's characters -- straight and gay, white and black, law enforcement and sex worker. It epitomizes the show's ethos regarding operation outside of the law.

In the world of The Deuce, if there's hell below, everyone goes.

Watch the characters of The Deuce navigate '70s NYC on Sundays at 9 p.m. on HBO.