After refusing to explain why he tried to kill himself at age 15, Steven Gaines spent five months in Payne Whitney, the fabled Manhattan psychiatric clinic, where he was treated by a sympathetic psychiatrist, Dr. Wayne Myers. He also found a wise mentor in another patient, Richard Halliday, the Broadway producer of South Pacific, Peter Pan, and The Sound of Music, among other hit shows starring his wife, Mary Martin.

I asked Mr. Halliday if he lied to his psychiatrist, and he said that everybody lied to their therapist a little, but that it was a waste to lie because it was the doctor's job to make you better. But what could I do? I couldn't bring myself to say that I saw Splendor in the Grass eleven times because I was in love with Warren Beatty. I lay awake in bed that night worrying. If I didn't tell him, then who would I tell? I tried to sleep but I had an erection that only a fifteen-year-old kid can have, and I finally broke down and masturbated, thinking about the lawnmower boy.

When I was done I was more miserable than ever, ashamed and degraded. So I got out of bed and put on my bathrobe and went to the nurses' station, where I asked for a piece of paper and an envelope. I sat at the desk in my room and as Lana Turner tears of self-pity rolled down my cheeks, I wrote, "I THINK I AM A HOMOSEXUAL" in capital letters, signed it, sealed it in the envelope, addressed it to Dr. Myers, and walked leadenly down the hall with it in my hand. I forced myself to put it in the mail slot at the nurses' station before I could change my mind.

I dreaded seeing him at my regular session the next day, but he never brought it up. Nor the following session. Maybe the nurses had lost the envelope? Then finally, at the third session, I asked, "Did you get the letter I sent to you?"

"Yes," he said. I studied his face but there was nothing. "I thought I'd wait for you to bring it up when you felt comfortable talking about it."

I welled up. "I hate myself," I whispered. "I'd rather die than be one."

"I see," he said. "Is that why you tried to kill yourself?" "I guess so." Okay, I finally admitted it to someone. But no great weight was lifted from my shoulders. To the contrary, there had been a kind of nobility in not telling that was now lost.

"Can you tell me why you think you're a homosexual?"

"I have feelings toward men."

"What kind of feelings?"

"Sex feelings."

"Have you ever acted on these feelings?" "No."

"How long have you had these feelings?"

"I don't know. I think I always had them, before I knew what they were, but they turned different a couple of years ago."

"Different how?" he asked.

"The feelings got stronger."

"Did the feelings get stronger about the time you started counting and taking things?"

I thought of Camp Lokanda and wanting to go chest to chest with Brucie Cohen.

"Is it possible that in trying to repress those new sexual feelings, the only way for you to cope was to invent magic rituals like touching things, and saving things, which would momentarily alleviate the anxiety? You were probably like a pressure cooker trying to keep your feelings in. It was like trying to plug up a volcano. And it manifested itself in obsessive behavior."

He let that sink in for a moment.

"But why am I a homo?"

"Do you know anybody who's homosexual?"

"You mean like Christine Jorgensen?"

"Who?"

"Christine Jorgensen. He's a homo, isn't he?" "I don't think so," Dr. Myers said.

"So why did they change him into a woman, if he wasn't a homo?"

"Christopher Jorgensen wasn't homosexual. He wanted to become a woman for another reason--because he didn't feel right being in a man's body. Is that how you feel? That you've been born in the wrong body?"

"No," I said, feeling insulted. "I feel like I've been born into the wrong world."

"Homosexual men don't usually become women."

"Yes they do," I insisted. "Or dress in women's clothing."

"No, they don't. Most live as men," he said. "Why do you say 'homo'?" he asked.

"That's what they're called, isn't it?"

"No, not really. It sounds mean the way you say it. I prefer to say 'homosexual,' which means 'same sex.'"

"I thought it meant 'men sex.'"

"No, it doesn't." He considered me as if he was trying to make a decision, and then, like he was confiding in me, sharing a great secret, he leaned forward and said, "You know, homosexuals can change. They can become heterosexual."

I was bewildered. "How?"

"I know men who were once homosexual, and now they're married and have children," he said.

"You?"

"No, not me. But other doctors."

"Does that mean they stopped being attracted to men?" I couldn't imagine.

"Absolutely," he said. "Homosexuality can be cured, like many other disorders. The key thing is, it's a tough row to hoe, and you have to really want to change."

Of course I really wanted to change. If it was possible for me to become normal, then why not? The world wouldn't be inside out, my whole life wouldn't be a sham. I could hold my head up. I could marry and have children, and nobody would be ashamed of me. I could listen to love songs on the radio and understand what it meant to be in love with a woman. I would jump through hoops of fire if I could be normal.

"Yes, yes," I said. "I really want to change."

"Then we'll begin next session."

Later that afternoon, when I went to work on the jigsaw puzzle with Mr. Halliday, I was grinning like the Cheshire cat. "Okay. Spit it out," he said. "You look like you're bursting to tell me something."

"I told Dr. Myers that I was a homosexual," I said, hoping to shock him.

"Good for you!" he cheered, not seeming surprised at all. He pretended to busy himself with his jigsaw while he waited for me to say more.

"Aren't you surprised?" I asked.

"At what?"

"That I'm a homosexual."

He looked at me for a moment and said, "Yes. I'm shocked."

"Did you know that homosexual means 'same sex,' and not 'man sex'?" I asked.

"How fascinating," Mr. Halliday said. "And what did your doctor say when you told him?"

"He said he was going to fix it."

"Fix it?" Mr. Halliday asked, his voice rising. "How is he going to fix it? Does fixing it take longer than cooking a cassoulet?"

I said I didn't know what a cassoulet was, and it didn't matter how long it took. I was hurt by his skepticism. Although, he did raise an interesting question. How long was it going to take to become heterosexual? I promised myself I was going to look up cassoulet in the dictionary as soon as I could.

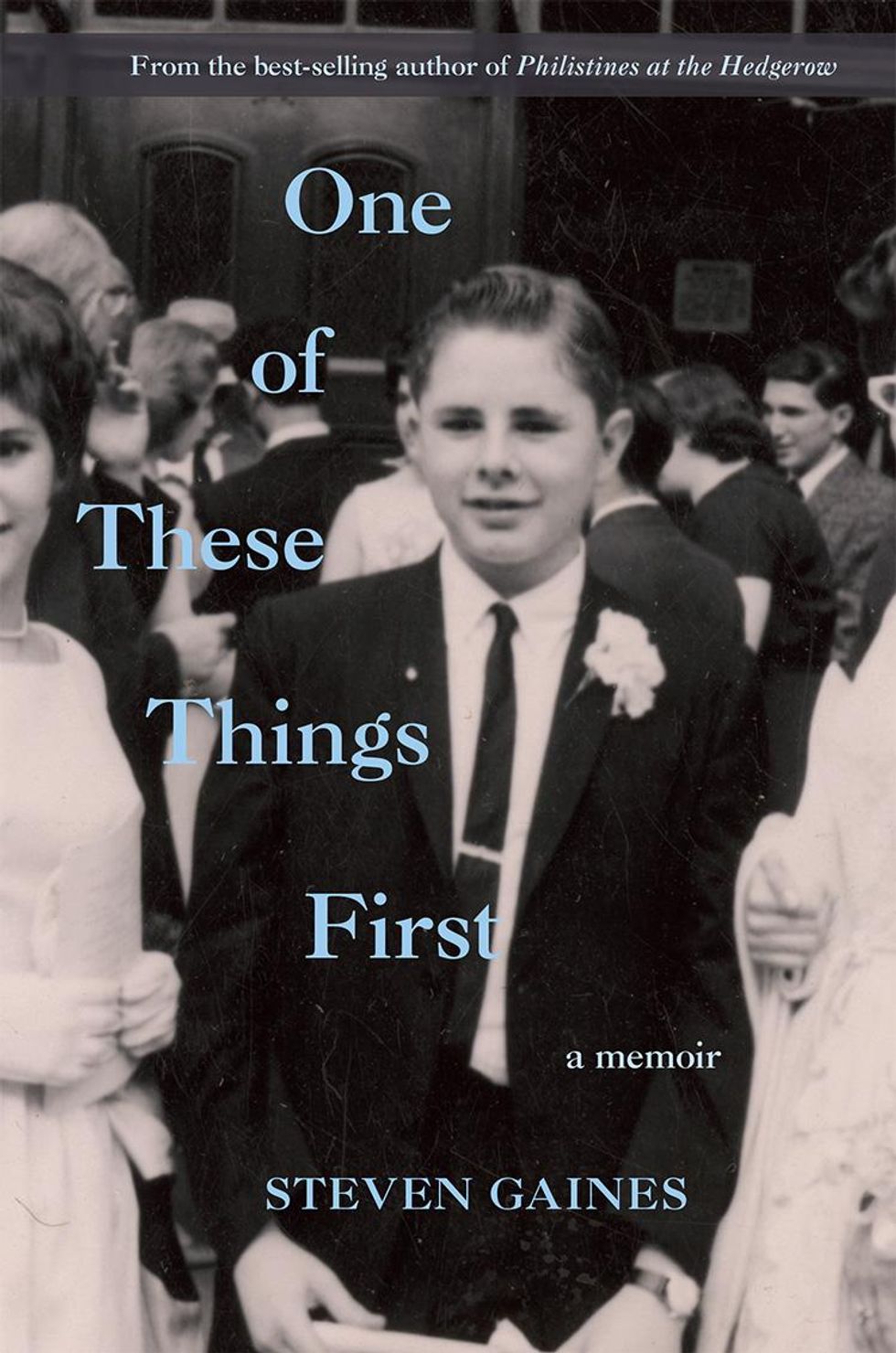

STEVEN GAINES is a bestselling author and his journalism has appeared in Vanity Fair, the New York Observer, The New York Times, and New York magazine, where he was a contributing editor for 12 years. His new memoir, One of These Things First, is available wherever books are sold.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes