Twenty years ago, I met Fannie Lou Hamer. I'd just graduated from high school in Cleveland. My sister, Beverly, and I were very active in the Congress of Racial Equality, and I met Mrs. Hamer at a party following a rally she'd addressed. Mrs. Hamer was sitting in a chair in the middle of the basement room and people were going up to pay their respects. She looked like the women in my family. She was stout, wore a wig, and had trouble with her legs (in her case because of the beatings she'd taken in jail). Even then I knew she was one of the most important people I would ever meet.

I didn't come out as a lesbian until ten years later. Since then, I've often reflected on what it would have been like to be an openly gay person in the Civil Rights movement. Reading Hamer's early statement supporting equal rights for women, long before most Black women dared to make the connection, I suspect her politics would have encompassed me as a lesbian. After all, it was the open-hearted spirit and hard work of older, poor Black women that made the movement possible. But the few known homosexuals in the movement -- James Baldwin, for example -- did not demand recognition of their homosexuality, and I'm sure there would have been no place for me as an openly lesbian activist.

One of the major barriers for lesbians and gay men was, and remains, black religious institutions. Traditionally an inspirational and organizing tool in the Black community, the church has almost always taken a stand against homosexuality. This condemnation naturally causes great pain among the large numbers of Black lesbians and gay men who want to maintain religious ties, which are also ties to family, culture, and home. That lesbians and gay men can be found in every Black church in this country -- even in the pulpit -- is hardly a well-kept secret. Yet, Blacks and other people of color pretend that homosexuality is a "white disease," and brand gay people in their communities as "white-minded." Many Black people still consider homosexuality a sin, an illness, a crime, or worse, tantamount to renouncing membership in the race.

Because of our shared status as outcasts, the Black community often shows great tolerance for members who do not conform to white social, sexual, and legal conventions. But for gay people, that tolerance is only extended if we stay closeted, "play it, but don't say it." Peaceful co-existence between Black homosexuals and heterosexuals is bought at the exorbitant price of our silence. The same sisters and brothers to whom racial passing would be anathema expect Black lesbians and gays to pass as straight and endure similar devastation to the spirit.

Many of the current generation of Black gay activists came through the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, and we see our situation in political terms. Just as we refuse to accept racist assaults, we also refuse to bow to attacks upon our sexuality, which is as crucial to our identities as race. The development of Third World lesbian and gay organizations, closely tied to the growth of Third World feminism, has prompted volatile debate about homosexuality in the Black community after years of no talk at all.

One of the stormiest confrontations occurred in 1983, during the fight to have a lesbian or gay speaker at the 20th Anniversary March on Washington. Congressional Representative Walter E. Fauntroy, national director of the march, polarized the situation when he reputedly equated gay rights with "penguin rights." Fauntroy later denied this statement, but also asserted that the march "would not be an aggregation of single-issue groups" and insisted that including proponents of abortion or gay rights might be "interpreted as the advocacy of abortion or the gay lifestyle." The very march being commemorated only added Black women -- like Fannie Lou Hamer -- to the speakers' roster at the last moment.

Then as now, the organizers' concept of coalition building was shortsighted. As another movement veteran, Bernice Johnson Reagon, has written, "You don't go into coalition because you just like it. The only reason you would consider trying to team up with somebody who could possibly kill you, is because that's the only way you can figure you can stay alive.... There is an offensive movement that started in this country in the '60s that is continuing. The reason we are stumbling is that we are at the point where in order to take the next step we've got to do it with some folk we don't care too much about. And we got to vomit over that for a little while. We must just keep going."

It took action by seven of Fauntroy's Black lesbian and gay constituents to turn the tide in that speaker controversy. Three days before the march, a group attempted to meet with Fauntroy in his office. When he failed to appear, they refused to leave until four of them were arrested. As a result of the sit-in (a pointedly appropriate tactic), an 11th-hour decision was made to permit Black lesbian poet Audre Lorde to speak briefly at the rally. The march's organizers, including Coretta Scott King, Fauntroy, and the Rev. Joseph Lowery, called a press conference and spoke as individuals in support of the federal gay Civil Rights bill. It was the first major public recognition by the Black Civil Rights establishment that our movements are related.

But gains on that side are being offset on another: gay white racism is as divisive as Black homophobia. The new professional profile of the proper gay activist assumes that gay equals white, reflecting growing conservatism in the white gay movement. For example, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), which lobbied heavily for gay inclusion in the 20th Anniversary March, refused to endorse this past spring's April Actions in Washington for domestic justice and against intervention in Central America and apartheid in South Africa. NGLTF's decision reflected the narrow scope of a white-oriented agenda, which favors assimilation over larger social change.

The failure of gay as well as Third World and feminist groups to adequately address our concerns has spurred autonomous organizing by gay men and lesbians of color. For the first time, we are stating unequivocally that coalitions fail when individuals must meet a white, male, heterosexual standard. Just as one of the goals of the Civil Rights movement was to get white people to believe we were actually human, at least human enough to use the same bathrooms and water fountains, homosexuals have to convince many heterosexuals that we are likewise human.

For me and many other Black lesbians and gay men, the Civil Rights movement is where it all began. It was where we learned that ethical and spiritual as well as political transformations were possible because we experienced the changes within ourselves. So, we expect no less a transformation from our own communities, both Black and gay. As Reagon says, "You can't tell me that you ain't in the Civil Rights movement. You are in the Civil Rights movement that we created, that just rolled up to your door. But it could not stay the same, because if it was gonna stay the same it wouldn't have done you no good. Some of you would not have caught yourself dead near no Black folks walking around talking about freeing themselves from racism and lynching. So by the time our movement got to you it had to sound like something you knew about. Like if I find out you're gay, you gonna lose your job."

This spring a friend, Suzanne Pharr, arranged for me to speak at Philander Smith, a historically Black college in Little Rock [Arkansas]. Suzanne, who is white, lives across from Central High School, the scene in 1957 of one of the cruelest battles to segregation. Daisy Bates, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People at that time, was a guiding force throughout the fight. When I was in Little Rock, I met Mrs. Bates, and just as when I met Mrs. Hamer, I knew I was in the presence of greatness. This time, however, I would not be left wondering whether my lesbianism would be acceptable to an important Civil Rights figure. Mrs. Bates came to hear me speak about being a Black woman, a writer, a lesbian.

Needless to say I was shaking inwardly even more than I usually am before I come out in public. In many ways, I owe my life to people like Mrs. Bates and Mrs. Hamer, and the thought that they might disapprove of me because I'm a lesbian is shattering. But I came armed with a number of lesbian titles from Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press and ready to talk about Jesse Jackson's inclusion of lesbians and gay men in his Rainbow Coalition. I also explained how being out has given me the strength and peace of mind to continue being political, and also to write. How there was a time during the height of Black power and Black nationalism when I doubted that I'd ever be politically active again, since I in no way fit their macho definition of Black femaleness. I know of too many gay people who were lost to the cause when movements made them pariahs. When I looked up from my notes I was relieved to see nods and even smiles. Later, Mrs. Bates had me sign her copy of my anthology, Home Girls. It was the feeling of acceptance that only your family can give.

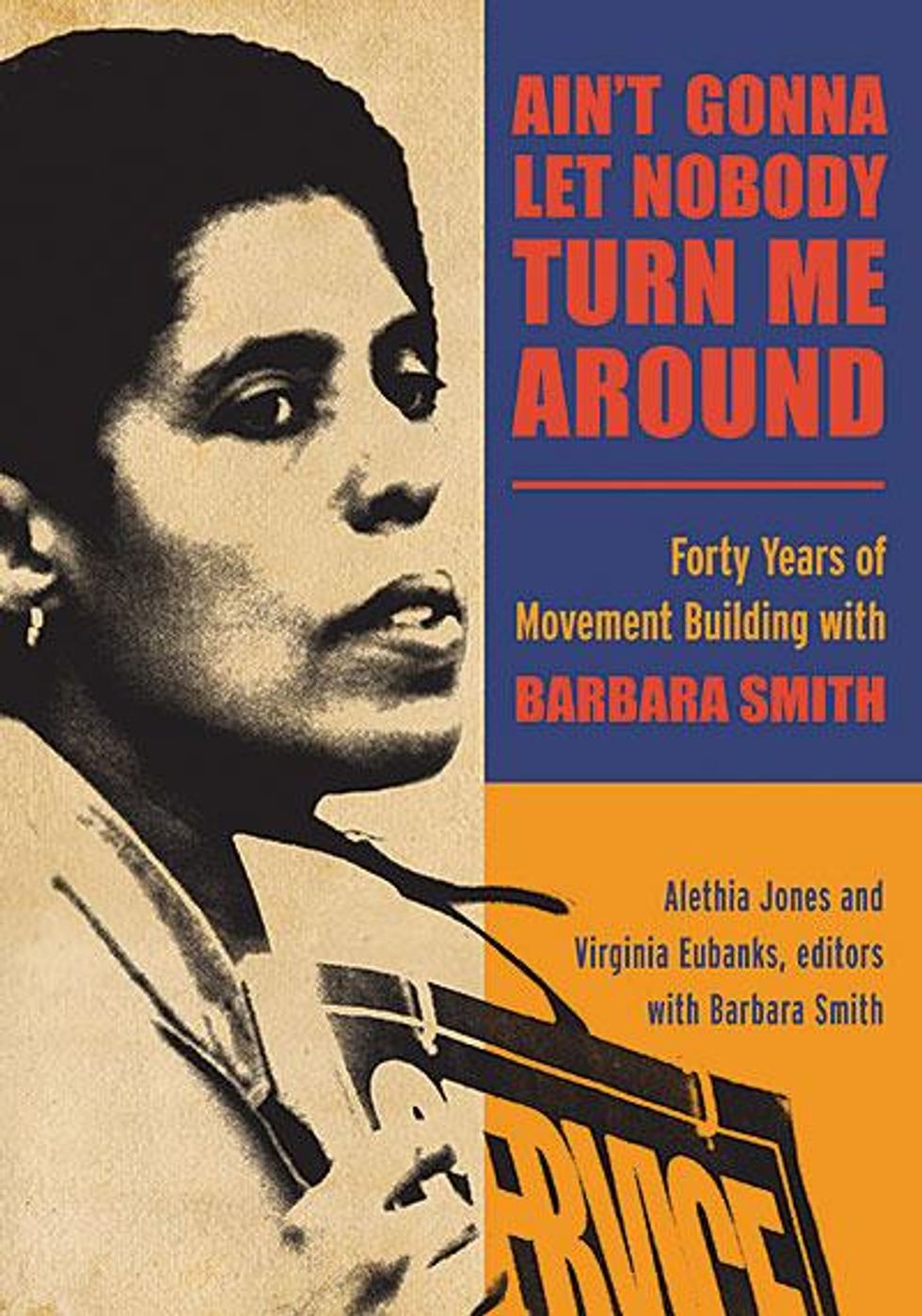

Barbara Smith is a public service professor at the University of Albany, SUNY, a former member of Albany's Common Council, and the author of The Truth That Never Hurts: Writings on Race, Gender, and Freedom.