The current Netflix hit tick, tick ... Boom! takes place in the early 1990s and follows Rent creator Jonathan Larson as he prepares for a workshop of a new musical, which he's been working on for eight years. Larson feels pressure to be successful before he turns 30 like his idol Stephen Sondheim, who figures into the film.

The coupling of that film and Sondheim's death over the holiday weekend at the age of 91 made me long for the days when I was struggling to be an actor, singing Sondheim's songs in classrooms and bars, and hoping for an unbounded and successful future as a musical theater star.

"One who keeps tearing around / One who can't move."

In the early '90s, as I approached 30, I left my job on Capitol Hill and moved to New York City with the dream of becoming an actor. It was an arduous couple of years of tearing around. I took classes at the Lee Strasberg Institute as well as HB Studio. To make ends meet, I worked numerous odd jobs.

I also did the occasional off-off-off-Broadway play. I was in constant motion and going nowhere.

But I carved out time to take singing classes because, like Larson, I had my own dream of becoming a star in a Sondheim musical. The very first song I chose to sing and work on in those lessons was "Send in the Clowns" from Sondheim's A Little Night Music. I had a singing teacher who was tough, so I worked on that song for what seemed like weeks on end trying to nail it. I don't think I ever did because it wasn't easy.

"Honor their mistakes / Fight for their mistakes / Everybody makes."

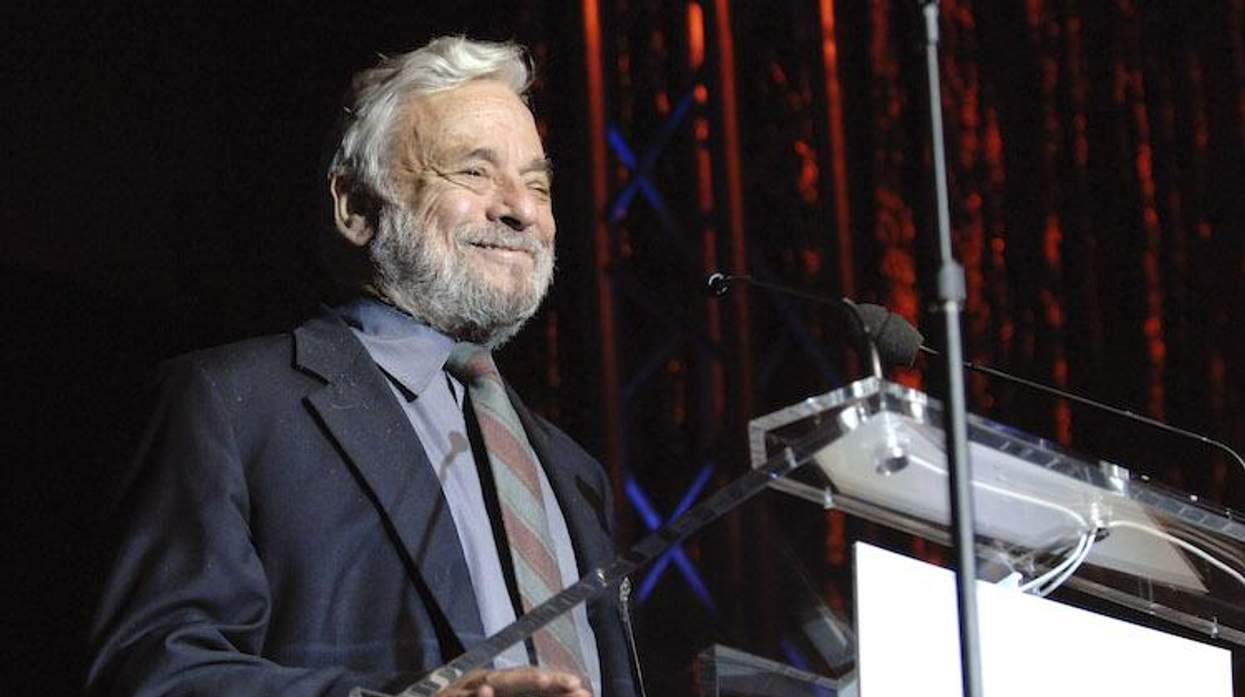

Sondheim made his work seem easy. That was his secret I suppose. The longevity of his career was unparalleled with hits in six decades. He won every conceivable award and honor. There were the nine Tonys including one for Lifetime Achievement, an Oscar, eight Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize, the Kennedy Center Honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and theaters named for him in Manhattan and London.

It is not hyperbole to say that he's in the pantheon of LGBTQ+ greats. Presumably, he will be mentioned in the same breath as Larry Kramer, Michelangelo, and Harvey Milk -- all of whom left indelible marks on the queer community.

Probably no one can get close to achieving all that Sondheim did in the theater world. But what impresses me most are the mistakes he made. He had flops, shows with bad reviews. Some with no box office windfalls. But he always came back from those mistakes and fought back, or accepted blame when things went wrong. Without any ego, he once said, "If they [the audience] don't like it, that's OK. If they don't get it, that's your fault."

For every A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, there was an Anyone Can Whistle (not a big hit). For every great reaction to A Little Night Music, there were audiences turned off by Passion. And for every critically acclaimed Sweeney Todd, there was a panned Merrily We Roll Along.

At the beginning of his career, after the huge successes of West Side Story and Gypsy, he said, "I don't think it ever occurred to me that I'd fail."

He did, but in the end for Sondheim, the wins far outweighed the losses. He showed us, through his music and words, how to cope with the missteps we all make in everyday life by just accepting what went wrong and to move on.

"So here's to the girls on the go / Everybody tries / Look into their eyes."

It's a stereotype and simply untrue to assume that all gay men love musicals. Early in life, I think I wrongly resented the gay men who outwardly displayed their love of show tunes -- most particularly while I was in acting school. I was still caught up in trying to tout my masculinity. I didn't want to be a "girl on the go," at least not in public.

One night I accidentally stumbled into the underground piano bar Marie's Crisis. I heard uproarious singing and wanted to find out what that was all about. I stepped in, looked into the eyes of others, and as a gay lover of musicals, felt right at home.

That bar in the Village became my favorite haunt. I could be free and different, and I could feel comfortable belting out the words to "Ladies Who Lunch." That was my second favorite Sondheim song. All the patrons in the bar would sing all of Sondheim's ballads, and each one held powerful meaning. The booze was not the reason we sang so loud and with such confidence.

There was something different about Sondheim's work. And I think it's because his lyrics were not over the top. Sondheim's work was sophisticated -- like ladies who lunch. More real. And the sentiments were honest, clever, serious, and could be painful. He depicted history, the consequences of love gone awry, and personal struggle.

"Thanks a bunch, but I'm not getting married / Go have lunch, 'cause I'm not getting married."

Sondheim had his own struggles with love. He became one of the few prominent voices to come out as gay, at the late age of 40 in 1970. This was a time when being "homosexual" was still seen as a scarlet letter and a crime. During that era, it was always assumed that if you were a man, working on Broadway, and particularly in musicals, you were gay. Sondheim did not hide that he was gay, despite the fact that he described himself as an introvert and a loner.

In an interview with Frank Rich for The New York Times, he said, "The outsider feeling -- somebody whom people want to both kiss and kill -- occurred quite early in my life." One could argue that's why Sondheim didn't marry or have a serious relationship until much later in life.

I thought that quote was a metaphor for another reason. It carried so much meaning, particularly for those of us who years ago felt like outsiders because we liked musicals, loved Sondheim, and were gay. We were less confident about ourselves around family and friends who would embrace us for who they thought we were. We knew they would feel much differently about us if our truths were exposed or if they knew we sang Sondheim in piano bars.

Was Sondheim a political firebrand for LGBTQ+ causes like marriage equality? No. But he did excel at his craft to the point where his words and songs gave some of us more confidence about our sexuality and emboldened many to come out. That was activism in and of itself.

Last year, actor Tituss Burgess spoke for some of us when he credited Sondheim with being instrumental in his coming-out. Burgess said, "I felt that I had all the tools just because of his music. And he's never written any overt stories about homosexuality or coming out of the closet, but he's written such human stories and stories of fairy tale. And the marriage of all of those composites helped guide me in a way."

There are those of us who understand that fairy tale and how Sondheim's work on the stage resonated with us in real life. And there are those of us, like me, who thought we'd never find love but did later in life. Luckily Sondheim finally found love and marriage late in his life. He leaves behind his husband, actor and talent representative Jeffrey "Scott" Romley.

"Another hundred people just got off of the train / And came up through the ground / While another hundred people just got off of the bus / And are looking around."

It was 1993 or 1994, and I was walking out of the subway, with another hundred people, coming from acting class, singing lessons, or one of my myriad jobs. I made my way to the corner of 50th and Broadway and was waiting for the light to change to cross. I was looking around, and to my left, there stood Stephen Sondheim.

I had fantasies of running into Sondheim and telling him about what a great performer I was and of him instantly casting me in his next musical. It goes back to being young, fearless, and full of hope.

But when the moment came, and for someone as verbose as me, I was lost for words. I felt so scared and inferior standing next to him. Like I had no business being in his proximity. The light changed, and we metaphorically ended up going our separate ways.

He continued to make more history on Broadway, and I eventually left the acting world and went on to a career in public relations.

"Where are the clowns? / There ought to be clowns / Well, maybe next year."

I look back on those years in the early and mid-'90s as a struggling actor/student and feel a deep sense of regret. Maybe I didn't try as hard as I should have? Throughout the last nearly 30 years, I have always wondered what could have been.

And maybe that's why I love "Send in the Clowns" so much. As Sondheim explained, "It was never meant to be a soaring ballad; it's a song of regret."

Since he died, I've been thinking about those formative years and my missed opportunity of starring in a Sondheim production. I enjoyed those years of struggling, trying, creating, and learning. I have arrived at a place of understanding that those years helped me come out as a gay man.

Sondheim helped give me happiness and freedom, and for a brief time in my life, he was a north star. I ultimately had to settle for being grounded in a desk job career, never making it to the stratosphere of being cast in a Sondheim musical.

"Isn't it rich? / Are we a pair? / Me here at last on the ground / You in mid-air."

Stephen Sondheim, through his work, will always fly high above the rest of us who never left the ground.

John Casey is editor at large for The Advocate.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.