In 2004, Gabriel Goldberg convinced the famously reclusive Jim French, founder and photographer of the Colt brand, to tell his own story to the public for the first time. The occasion of this special issue of Men magazine -- once part of the Advocate family of publications -- was French's retirement and the turning over of the brand to John Rutherford. French's influence on gay male visibility is comprable only to Tom of Finland's in terms of cultural saturation. (Google "Colt model gay" and you get almost 2 million results.)

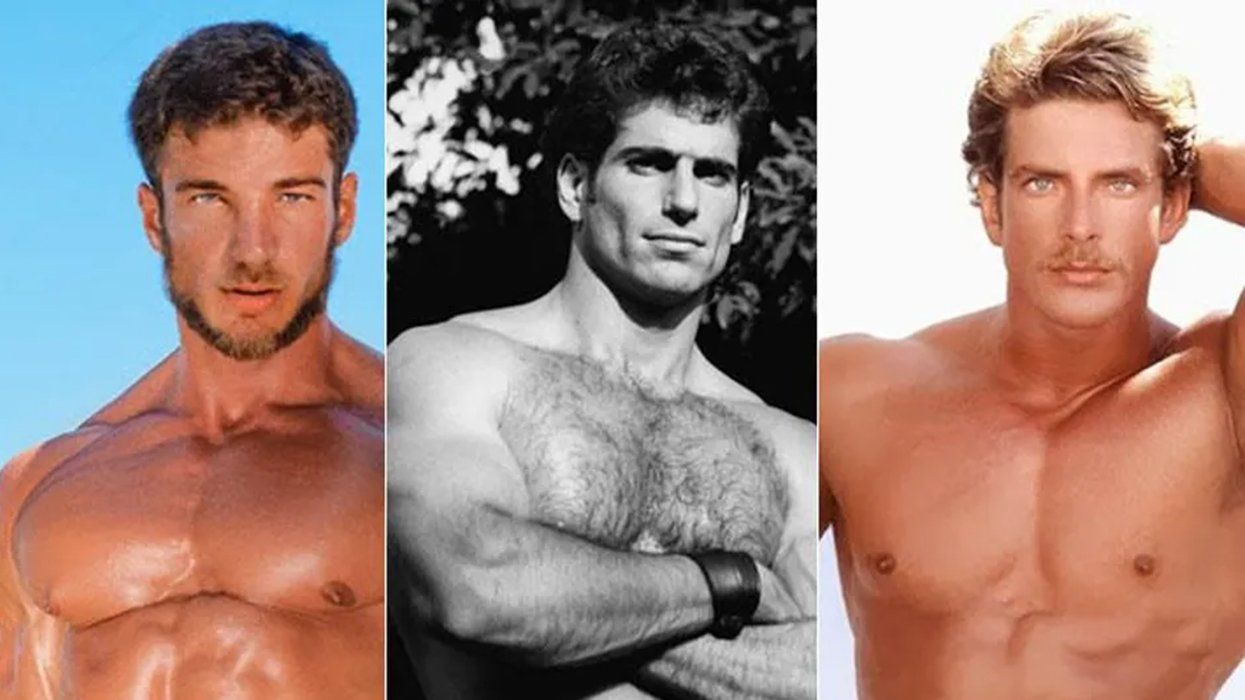

Jim French specialized in a very masculine ideal -- some would say unattainable. Yes, some of his models identified as straight. Most of his models were white men. Many of them had the kind of bodies many gay men only dreamed about. But the same could be said of Michelangelo's subjects.

These days we are experiencing new concepts of masculine and feminine. Gender fluidity represents a new freedom away from the constriction of the classic cisgender "butch" man. But in Jim French's day, it was a contrary notion to portray gay men as hypetmasculine and butch.

Regardless, Jim French influenced the ideals of male beauty forever with astonishing skills, an eye for the subtly erotic, and often an ironic wit. -- The Editors

Life Thru a Lens

Jim French: In His Own Words

After 36 years of photographing some of the world's most astonishing-looking and amazingly built men, master illustrator and photographer Jim French, founder and creator of Colt Studio, is retiring. With the company now owned by John Rutherford, former president of Falcon Studios, the iconic photo-making machine of the erotic, masculine image has come to the end of a glorious, golden-muscled era. For the first time in his illustrious, almost-four-decades-long career, JiIm French talks about his life before he got behind the lens, where his alter ego "Rip Colt" came from, and why he's finally ready to leave it all behind.

As told to Gabriel Goldberg

First off, let me register my discomfort with doing this kind of interview. It's based on the fact that I am from a generation in which promoting oneself was considered bad form and bad manners. I know that today that adage would have wiped out the careers of Andy Warhol and Madonna. But I just don't think what I have to say is all that important. What I've had to say is seen in the images. I don't really think who's done them is interesting. My model for this, if you will, is Irving Penn. Irving Penn is a contemporary of Richard Avedon. Avedon has always relished publicity. You don't know anything about Irving Penn, other than his photos, and that's what makes sense to me.

I went to the Philadelphia Museum School of Art for four years, and then I went on active duty in the service for two years. I took my basic training at Fort Knox, Ky. I think Baghdad today is probably similar to what that was like. Then I was stationed in Fort Mead, Md. I met all kinds of people I'd never met before, and I was glad I did it. I had been in the reserves for two years previous to that, so I went in as a noncommissioned officer and became the pianist for the officers' glee club. At the time, if you had told me that later I'd say I was glad I did this, I would've laughed really hard. But in a way it prepared me for Colt because I had to deal with people that were not in my sphere.

After the service I went to New York and worked freelance. I had an office on Madison Avenue, and I worked for BBDO, Young and Rubicam, and all of those high-end advertising agencies. I drew everything from storyboards for commercials to comps for ads. And from that I got an agent and I started doing fashion drawings for Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf. I was happy doing that; it was very lucrative. This was in the '60s in New York, and storyboards were quite new. I drew enough tubes of Crest toothpaste to last me a lifetime.

Then I ran into a friend whom I'd met in the army, and we had dinner and he asked me what I was doing and I told him. I don't know why he said it, because he was not gay, and in hindsight, it's not a gay statement, if you consider the time in which it was said, he said, "Why don't you do drawings of bodybuilders and we'll sell the reproductions." And that's the germ of it all.

I certainly was not going to give up my day job. So I kept doing what I was doing professionally and then I did a set of, I think it was initially six drawings. I came up with the name Luger because I liked the way the word looked. I thought the umlaut was interesting, and it just seemed to be a masculine icon. So we went with that.

In those days, there were very few avenues for this kind of art. People today don't realize what the climate was like in the late '60s. When I started Luger, frontal nudity was considered obscene. Early photographers such as Lon in New York were being prosecuted if their pictures showed a glimpse of pubic hair peeking over a posing strap. This was very, very restrictive. It wasn't until around the early '70s that through a Supreme Court decision frontal nudity per se could not be considered obscene -- thereby validating all the great masters who had painted nudes. It was awfully generous and considerate of the Supreme Court to validate what everyone from Caravaggio and Michelangelo had done.

Joe Weider was starting up in those days. He had an office in New Jersey and he was publishing some low-grade "gay" publications like Young Adonis. They were fairly large-sized publications; everyone was of course completely covered, but for that particular clique who was into body worship, it functioned OK.

I think most people knew what it was, but in those days "gay" was not on the radar. There was so much subterfuge that you didn't acknowledge it. I suppose it was the golden age of masochists, because if you wanted to really make your life a living hell, you could be obviously gay. Ask Quentin Crisp.

When a book came out, like The Well of Loneliness, it was a scandal. Copies of Henry Miller's Tropic of Capricorn had to be smuggled in from Europe. Today it would be book of the month club on Oprah. It was a very restrictive time.

So I started doing these drawings and we were able to place a few ads in Weider publications and were just amazed at the response. They were not frontal nude, but they were sexy. I'm old-fashioned enough to believe that when you see it all, it's not as sexy as when you let your mind create what you want to be there.

Was I surprised by the response to my images? Yes. My partner and I had no idea that this was going to happen. It was a long shot. I did another series of drawings. My partner at the time was a very intelligent person, but basically, he was not a good businessman. It became clear to me within six months that I could create the product and it would be popular, but he was not following through in filling orders and doing what is required for a business. So we came to an agreement, and in 1967 he bought me out.

Around this time, I had met someone in New York whose name was Lou Thomas, and Lou Thomas was somebody whom everybody liked. He was part of the leather milieu, but he was intelligent and bright and he knew that it wasn't working out with my other partner. So after I was bought out of Luger, Lou Thomas and I set up Colt Studio that same year, 1967.

We were partners for four or five years until he took a lover that nobody could deal with and forced this person into the company. By that time we had six employees, and it wasn't just me who couldn't deal with Lou's lover, it was all the other employees. So we parted company, and he started Target Studios. He only had that for a year or two, and then unfortunately became an early victim of AIDS.

I decided around then that I really didn't need a partner, I needed a business manager. By this time I had been making several trips a year from New York to California because the weather was better out west -- so was skin quality -- so I decided to move. The segue was fairly easy because I had met people on the West Coast when I came out to sell originals of my drawings.

Just to show you how far back I go, I was in Florida on vacation -- this was before I moved -- and I bought a new camera that had just come out. It was called a Polaroid. One of the reasons they had introduced it in Florida was because heat was a factor in developing the pictures. I remember the black-and-white film came with two thin pieces of hinged aluminum and as soon as you took the black and white print out of the camera, you put it between those two pieces of aluminum and you put it in your armpit, so the heat would develop it. I go way back. The wheel had been invented, though.

So for the drawings that I was doing, I wanted to improve them, I wanted to get them to be more believable. Polaroids were the answer. I always thought that my work and Tom of Finland's were apples and oranges -- he did his thing and I did mine. The subject matter was the same, the approach was completely different.

And I think one of the reasons is, his art was a venue for his sexuality. My drawings were a result of years of academic study, years of fine art. Ours was from completely different backgrounds, so the products were different.

My approach to it was, I think, more subtle. I don't know why, when I met him, I expected him to look like his drawings. Because it's a truism that artists usually draw themselves. Particularly if they're not very good draftsman. So with that in mind, I expected Tom of Finland to be this behemoth who made the ground tremble. Instead, he was a quiet, shy, sweet, dear man whom I liked immediately, in spite of his work. I would have liked him as a person if he were a ribbon clerk. He was just very nice. And then I realized after meeting him and looking at his work again that that is the world that is his id. That's where his fantasies are. I've always felt that I worked in a fantasy world because the people in the drawings are polished to perfection. And in the photographs, with all due respect, they don't look like that walking around.

Of course, lighting is one of the components. But a photograph is ultimately the photographer. That's one reason why I've never wanted to do an interview, because my private life belongs to me. Where my taste is, what I try to achieve, is in the photographs. And that's all that's necessary to know. Of course, if you have to start with good eggs, so I tried to find people who were very attractive and then make them look as impressive as possible.

I didn't move to California until the beginning of the '70s. The reason that I mentioned the Polaroid was because in order to get the drawings more convincing, I took my little Polaroid camera and I would hire people to pose for me. Then I would use those Polaroids as source material for the drawings to get them to look more realistic, more powerful. Back then, my models were hookers. They were better-looking back then. They had to be -- there were fewer of them.

[ Related story: Artist Spotlight: Jim French's Polaroids ]

Well, I was at my house at Fire Island one summer, and it occurred to me that in the time it was taking me to do these tight renderings, I could take a photograph and sell reproductions of it. So that was the next segue from drawings to photographs.

I had no background in photography at all. But in one way, I had the best teacher because I made every mistake possible, and that's how you learn. My first camera, after the Polaroid, was a 35mm. I still had it in my hand when I reached the bottom of the swimming pool at a house where I was photographing in Beverly Hills. I just backed up into the pool.

So we started selling reproductions of the photographs. We would do ads in gay-type magazines, and we did trades for a while: We would get free ads if we let the magazine have so many pictures for their edition. But then I started feeling uneasy because I've always felt that because something is gay, it didn't have to be sleazy. I am not sleazy. The way I live is not sleazy. It's just not part of me. And that's one reason I'm happy to retire now, because sleaze and explicitness is in, and that's not my turf. I don't feel comfortable with that. I'm not putting it down, I'm just saying I don't feel comfortable with it.

My work is unique in so much as, it's not Avedon and it's not Nan Goldin ... it's more classical because of the background and the training. You see, I decided early on if no one ever took another photograph of a nude female, this planet would have enough of a supply to last it until the second big bang. But nobody had done forthright photographs of male nudes. George Platt Lynes had done them, but no one ever saw those during his lifetime. The best one of them all, if I had to say there was a photographer who really rang my bells, was a photographer named Clifford Coffin. He was a photographer for Neiman Marcus, and he did beautiful work. His personality, unfortunately, was irascible, and finally Neiman Marcus couldn't get models to go to his studio.

Somehow or other, I connected with him and he showed me his private pictures, and I was just amazed. Very few of them were nudes. That wasn't what he was interested in. He was interested in masculinity. He was interested in the erotic male. I mean, he did nudes of Yul Brynner, but they were just nudes. They weren't anything of any consequence.

But when he did his private things, that really got to me. I'd never seen anything like that. They were beautiful, they were elegant, they were sexy. Those were things that I felt comfortable with. But as I say, he was a difficult person, and in the end he not only burned all of his pictures, he burned his house right down to the ground. He lived on Park Avenue South, and the last I heard he'd moved to Hawaii and was derelict. Sad.

The reason I picked the Colt name was because it was my understanding that it was the American equivalent of the German "Luger." We started out with a pistol image, but soon after we started Colt Studio, I didn't like that image. I wasn't doing violent pictures. Although I would dip into the leather world for illustration, from time to time, it moved into the young horse pistol image. And I really thought the Colt image was fresh, it was healthier, more positive. So that's where Colt came from.

There was a model that I worked with from San Francisco, whose name was Alan Albert, and we started corresponding. He sent me pictures of himself, amateur pictures, but they were taken by someone by the name of Rip Serby. I don't know who he was, I don't know who he is. I never met him. I just thought that was a good name, and Colt had to become more personal -- it had to become a persona. So I used Rip because there aren't many people called Rip, even today.

People seemed to like the work well enough to buy it. It gave me the financial stability to say goodbye to fashion illustration. I had been very fortunate with the timing element. When I started doing this, the gay rose was just starting to bud, so I was able to go with it and see it begin to flower.

I always, always paid my models. I think it's the height of conceit to think that somebody would work for me if I give them a print. Maybe I'm wrong. I always felt if you worked, you should get paid. I don't understand photographers who photograph people and get them to sign a model release and they don't pay them anything. I could never do that. I'd be embarrassed. I always prided myself in the fact that it was always a professional experience.

Now, that covers a lot of ground because these "experiences" have been different with every model. Everyone is unique. I never know what I'm going to do with a model until they're in front of the camera and inspiration takes over. My assistants ask, "Where do we go next?" I don't know! Give me time to think. I don't have a storyboard. It always comes from the moment, the place, the model and the temperature ... whether I'm bored or not.

One of the things I had to learn early on was how to deal with people. There were those who came into my orbit that I had no tangent with at all. I didn't understand them, they didn't understand me. They were trying to make some money. So I had to learn not to tell these people exactly what I thought of them. That was not going to be productive. And I knew after the last picture was taken, I would never have to see them again. So I learned to endure. And that did not come naturally to me. That's something this business has given me as a freebie.

I've always told my models unless they were running for pope, I'd never heard of any of my images creating problems for someone's career.

I never worked with agents; I met people. When they worked for me, they had a good time, they knew it was business. I've only had something beyond that with one person; that was 18 years ago and we're still together.

Models would refer friends. And the selling point, basically, was the work. I've never asked anyone to do anything they didn't want to do. There was no point in coercing people, so it was never a case of anyone coming back later and saying, "You made me do that." I never did. I would not have done that.

Finding exceptional people to get naked in front of a camera became more difficult, but looking back it was so much easier than it is now. People know if they do nude photography now, it will probably show up somewhere. Like the internet. And that may or may not be a problem .

When I took someone's picture, I tried to make them look as attractive as possible for my standards. My standards are not theirs. I never tried to impose my standards on them.

When I photographed Ben Cody, for example, we found him in a trailer camp and cleaned him up. Since he was cooperative in letting me give him a look, and being cooperative in the work that ensued, it was a nice experience. But I would never say to him, "Now you look wonderful." Because I don't know if he could even understand that. He hadn't asked for a makeover.

But if you're a Pete Kuzak, you're going to walk around looking awesome all the time. I had nothing to do with that. But finding models is difficult. I mean, Pete took over two years. From the first session I did with him until I got him to let the body hair grow took over two years.

Now, John Pruitt was so impressive anyone would have to look at him. He was the kind of person who elicits the sound of dropped flatware in a restaurant. One of the most attractive things about him was that he wasn't conscious of that.

I think I began my work with him around 1984. I had learned enough about photography at that point to wish I had been a better photographer. Because, I'd only been doing it for 20 years or whatever, and I knew what good photography was and I knew what my technical limitations were,

Looking back at some of his pictures, they're not bad, but the most I was able to accomplish with him was to record John Pruitt. I didn't have the skill to interpret him. Most of the pictures of John Pruitt which are the strongest are the ones that present him in an impressive way. I don't take any credit for the photography on what was done of him. I just tried to record this glorious creature who was in front of me. I wish I had been a better photographer. But he was very patient and understanding.

I know the first sessions we did were to allow him to make some money because he was getting married and he wanted to go on a honeymoon and get set up. That was his initial approach to working with me. But we became friends and certainly after his marriage, it was like family. I became godfather of his first son. It was a unique experience. You don't get a John Pruitt very often in one's life. If you get one, feel lucky.

I would say 80 percent of the time we've said no to models who wanted to work with us. If I looked at them and I thought I could work with them, if their personality was such that it was flexible ... because most people who look into a mirror don't see what's there. People would contact me who would see the Colt photographs and in some way thought they could look like that. I was not about to ruin their day, I was always tactful, but thank you, no thanks. And as the years went on, I became more and more selective because time was moving on and if I wasn't enjoying it, why do it?

I worked with models over several years because they were handsome and didn't work for other photographers or get publicized in Advocate Men or Blueboy. I was really convinced they only wanted to work for Colt. If the sales of their magazines or photo sets was strong, I would work with them again. Pruitt's photographs were taken over the course of five years. Once he became married, he couldn't afford the time to spend in a gym. So he changed his priorities, which was fine because to my way of thinking, it was part of growing up. He took the responsibilities of a marriage and a family on and dealt with them.

The transition into movies started because someone gave me a little Mizo Super 8 Camera. I did a lot of things at Fire Island, shooting seagulls, things like that. And then, I don't know, I did movies because that's where things were going. It got to the point fairly early on where I had to decide, Am I going into this full time or not? And I just made the decision not to. I mean, I did them because they were popular and people liked seeing them.

You can create a fantasy in a still picture, motion reduces that. Motion and sound dissipate it. That's one reason why I never did any live sound in the movies.

I wish I could have done more beautiful movies. There were two movies I did that I was pleased with: The one we did with John Pruitt in Puerto Vallarta, and the other one was of Franco Corelli. His was done on an impressive estate in Montecito. I think the title is On His Own. In both cases, I was able to work with musicians who were very, very talented. Music is such an important component. For the Pruitt movie I had rented a big house and was one of a series of movies I did called "Legendary Bodies." These were films just for people who enjoyed seeing magnificent physiques. It was erotic to the point of them being naked, but there was no sexual activity. And we advertise it clearly that way. These were not popular; they didn't sell in numbers that would have made it feasible to do extensively.

I like Ferragamo shoes. I like excellent restaurants. I like the car I drive. Jim French couldn't make a living and allow me to do those things. I had to straddle what I like to do with what my audience wanted to see. I was able to do that to the degree in which I could live comfortably and on my own produce images which I knew going in weren't going to make money.

Working for Colt Studio allowed Jim French to work also. That's why I was able to please myself and do what I wanted to do and be creative for Colt Studio.

I did landscapes early on. I was very interested in learning how to use the camera. I thought for a while I might get into landscape painting because there were landscape photographers like David Muench, who does the most beautiful, beautiful landscape pictures. But it's rough. It's tough doing that.

Ansel Adams's work is superb, but I don't think people realize what an artist he was in the darkroom. He would spend days on one print in the darkroom and the result was just exquisite. He's as much an artist in the darkroom as he was behind the camera. He's brilliant, I just love his stuff.

I've only been in a darkroom once; I tried to develop 72 exposures in turpentine. That was enough experience for me.

When I'm shooting, I just feel like I'm doing my job. There've been segments in my life ... I studied music for 12 years. And then I dropped that when I went in the army. And when I got out of the army, I was an artist for 15 years. And then I became a photographer. I have no problem walking away from it.

With the introduction of digital cameras and extraordinary retouching and things that are going on now, it's a very interesting time. However, the adage "seeing is believing" no longer applies. If I ask one of my assistants to take a branch out of a frame or something, he says, "You can just take it out in Photoshop." No, no, no. I want my picture to be as exact as possible. Occasionally I will go for the caught moment, but usually my work is a construction. That's just the way I did it.

You see, I studied illustration, and as soon as I graduated, illustration went right out the window. But my background in that is so strong, it helped the photography a lot because I could make the imagery strong. I knew how to do that. It's a different approach, and people have said to me, "Well, you know, so-and-so's copying your lighting." I think, Copy away. I mean, if you don't know why I came along, there wasn't anyone I could copy, because nobody was doing what I did.

I'm not aware of the effect of my work. I never will be. In my house, I have one drawing of mine hanging that's very nice and not very commercial. It was released; it's on page 1 of some magazine. But,I don't have that kind of ego. I would never think of living with my work.

If my work reaches a wider audience once I'm gone, I'm not going to care. I knew Andy Warhol when he was doing little shoe drawings for Henri Bendel. I saw the explosion of him. I saw the art world pick him up and put him in the 21st century. I must say, in Andy's defense, I never heard him say he was terrific. His trick was to get other people to say it. But to me, you know, anybody can do an Andy Warhol. Try copying an Ingres painting or drawing. You can't!

I don't regret not having had formal schooling in photography because I never wanted the technique of the photography to overwhelm the subject. Take Blue magazine. Now, the art director doesn't believe this, but people buy that publication because of the men who are in it. They do not buy it because of the layout of the book. And right now that magazine has layouts in it that I can't even read -- some of the copy's here, some of it's there, some of it's in this color, some in that. It's illegible to me. But that's their thing; they don't like doing that.

When I would do magazines, even the coffee-table books, I never wanted to get so arty that it was distracting from what it is people wanted to see. They don't buy publications for its layout, they buy it for the content, so I never got very fancy layouts and things, because that's the frame of the picture. If the frame is so ostentatious, it detracts from the picture. So I don't think I have any regrets.

There are men I would have liked to have worked with. There are people who I know had worked for other photographers, but the photographers used it as a sexual approach. And so I lost the opportunity with them because naturally they would equate everyone ... you know, you put your hand on a hot surface and you're not going to put it back there if there's a chance you think it's going to be hot. So I regret that. But not to the point where it keeps me up at night.

I'm beginning to be happy now. It's taken me a while to get used to not having the stress, the problems. I give those all to Mr. Rutherford. Who fortunately seems happy to assume them and obviously up to the task.

I think John's a fit. I've only known him six months, but I've always felt that Falcon and Colt were apples and oranges, both popular on their own terms. Colt's success was never comparable to Falcon's.

Anyone who's ever done pornography, even if they end up going to jail, always makes a great deal of money. Porn is what people want. For one reason, it's what people have been told they can't have. Falcon has always been successful, and I think John will make a new Colt Studio and I see no reason why it shouldn't be as successful as Falcon, if not more so.

I'm not sure what the new Colt will become. I would hope that at some point, John connects with a very good, creative art director. Certainly John will have inherited imagery that is timeless. That is something I was always conscious of: to try and not make the pictures dated. Very few people I worked with in the '80s had long hair. I never photographed anybody who had lightning bolts on their shoes. Those things are part of their time. Because of that, I think the images have a long commercial life.

Of course, they've got to be dated to a degree. But not to the point you notice an article of clothing or a cut of hair or background which says '80s or '90s. Those are things I always kept out of the frame.

It's difficult to say which decade I enjoyed the most, because they've always been full of uncertainty, full of stress. It's never been easy. It's always, always been difficult. Because I was trying to bring quality into a milieu that had never seen it before and didn't know what to do with it. And if you're trying to bring quality into an industry that's not interested in that, it's very difficult. It's not so much a matter of carving out a niche in history as it is hacking out a place. There are obviously people out there who wanted something better, something more. Who didn't want images that were necessarily all that explicit. That was me. I was keyed in with them. And that worked. But that was a small, select audience. It still is.

I don't know that things have changed all that much. I think porn is being more widely accepted. But in many ways, getting "special" people to do that kind of work is always going to be difficult. I see my work as erotica, not porn. Frankly, pornography bores me, because 99.9 percent of it is lacking the one thing that makes it successful. And that is, it's not erotic! It's people doing a job for X amount of dollars in front of the camera. Pornography does not interest me. Photography interests me. And making marvelous-looking men look their most impressive. That's what I've always been about.

Looking at the work as a whole, it has a historical niche, which can't be disputed. Even I can't argue that. But I don't see where what I did is going to continue. There's not a photographer out there that ... certainly Kal Yee has the technical expertise, but he's not going to do any nudes, which is fine. I'm not saying that's dishonest. That's just his choice. But my choice early on was to be straight forward, and not ashamed of it. There are levels of eroticism. The more you push the porn envelope, the more response you're going to get. I think it's going to have a much, much wider audience now. And that's fine. I just did what I did.

Since the photograph is ultimately the photographer, my work is ultimately me. My work was a distillation of my life. And my life is a unique life, like everybody's. So it'll be somebody else and it'll be their life that they'll project. I wish them well.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.