CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

COMMENTARY: It is more than a little embarrassing for me to admit this, but I am one of those Americans who, in jest, has referred to Canada as "America's hat." Yes, it's a silly joke. A tired, unoriginal, and silly joke, but for all intents and purposes, a benign one. But still, it makes me cringe to think that there was a time when I was a stereotypically pompous and arrogant American, making fun of any and everything that was foreign just because I felt had the power to do so. I was not, however, without my reasons.

During my first stint in Canada as a single 25-year-old, I was constantly homesick for the States, frustrated at finding myself in a large, booming metropolis that seemed comparable to New York City on the surface, but kept falling short. My only respite was the high value of the American dollar and the excess of Toronto boutiques with which to spend it. Shopping successfully got me through my boring days off work, but still I complained. Canada's clubs weren't as good. Everyone there was passive-aggressive. You couldn't find good falafel at 2 a.m. I complained about the lack of diversity and I complained about how weird it was to discover that Canadians really did ask "eh?" at the end of their sentences, and I counted the days until I would be back home in my sweet, comfortable, awesome United States.

Of course I had no idea then that four years later I would be making my way back to Canada, even further away from my beloved New York, where I would be spending an indeterminate amount of time calculating the myriad differences between me and the Canadians by which I was surrounded. By this time, I was three years into a relationship with my partner (in love, not business!) and we were anxious, even excited for our big move. This was not just because we were heading to Vancouver, but also because we were going away from New York.

I had begun dating women shortly after I returned to New York from my initial time spent in Canada, and I was consequently shocked and horrified to discover firsthand what a homophobic place New York could be. Manhattan's Chelsea neighborhood is a haven for attractive gay white men--but for me and my fellow queer sisteren? We had no haven in the city, and the fact that I was in an interracial same-sex relationship was like a double-edged sword. We got much more negative attention than same-race queer couples, and it was at times unbearable.

Having never been interested in public displays of affection, my partner and I found ourselves rarely even touching each other in public, living the lives of what we jokingly referred to as "roommates." It was not out of shame or embarrassment, but rather fear of vocal and physical retaliation. We had been threatened before. We had been yelled at, called nasty names, sneered at and whispered about. Teeth had been sucked. Eyes had been rolled. Snickers had been hissed. Eventually no responses were any better or worse than another. It was all hateful. A peck on the lips for goodbye became an act of defiance for us, quick and unromantic. We were a loving, committed couple, having become legal domestic partners in the eyes of the law, yet we were afraid to hold hands on the subway. We were exhausted from letting spiteful, self-righteous New Yorkers set the parameters that would rule our public lives, and Vancouver offered a change (for better or worse, we had no idea, but we were eager to find out).

To get to Vancouver, we drove across the terrain of our United States for eight days, taking in the dry land and the forever sky and the strip malls that rose up and down into the dirt. We bit our lips when requesting a "single, not a double" in the hotel lobbies of dingy, nameless towns. East coast, Midwest, west coast--every new city we entered got the same treatment from us: cold, and cautious. On the final day of our journey, our most dreaded day, we pulled up to the Canadian border. My previous complaints about Canada had been superficial, just childish ridicule that made me feel important and cool. But now I was older and wiser and less interested in bragging rights and more interested in civil rights. I had no idea what my same-sex relationship would mean in Canada, or more importantly, what it would mean to the Canadians.

My hands shook as I handed the patrolman our passports, explaining that I had a file started on my behalf and that I was coming to Vancouver for work. He asked who the woman next to me was. I said, "she's my partner" in a strong voice, so that he wouldn't know that I was nervous, and I reached for the folder in my bag that had our documentation issued from New York State citing that we were domestic partners. I knew he would want to see them, and I felt my mouth get sour and my heart start to beat faster. My body was getting ready for the fight that I knew was to come, ready to insist to this stranger that she was my partner and had a right to be there with me in this new country.

But the patrolman waved my hand away when I tried to hand him our certificate of partnership, and he asked if Claire wanted to work while she was in Canada with me. Claire and I looked at each other and shrugged, and she answered, "ummm... sure." We hadn't even known that this was an option.

An hour later we walked back to our car, minds blown. It was the easiest, most painless experience I could ever remember having with government employees of any country. I don't know what we were expecting; the Canadian stereotype I was familiar with was for its citizens to be non-confrontational and easy-going, and our exchange certainly lived up to that standard. But I'd had high expectations, once I came out, for New York City to be a warm and inviting place that celebrated the diversity of all it's inhabitants and embraced me and each cute girl I wanted to date. But New York had ultimately let me down. I guess I was expecting the same from Canada, too.

Thankfully, I was wrong. Our experience at the border set the tone for the next three years that we would spend in Canada. We are now no longer relegated to "roommate" status in anyone's eyes. We hold hands whenever we want and around here, no one has ever batted an eyelash. I have kissed my partner's cheek while waiting to cross at a red light and no one has ever honked at us. I introduce her as my partner when I meet new people, and I study their faces closely, but no muscles twitch in them.

Once when we were holding hands while crossing the patio of a crowded coffee shop filled with older Italian gentleman, one of them yelled out at us in a gruff, accented voice "You two make a lovely couple!" I'm fairly certain this was a genuine acknowledgment on his part, but either way, it sure beats hearing someone yell "Sodomites!" at you from their car window on a Brooklyn street corner.

Whenever we go back to the states, we are reminded of how unprogressive and unapologetic our fellow Americans are regarding our relationship. I notice a difference in other people's body language and energy as soon as we get to the U.S. customs area inside the Vancouver airport, and from there, the hits keep coming. But strangely, this has not made me reconsider my affinity for the U.S. I still feel excited when I step foot in one of it's cities, when I meet fellow Americans who are traveling in Vancouver, when I go back to NYC, or to visit my family, or to Claire's hometown.

The United States is a work in progress, but it is still my home. It feels comfortable and easy, and even my struggle as a queer woman of color is necessary and important to the history and the future of the country. I have learned now that embracing one territory doesn't mean I have to exclude the other one, and it is entirely possible, healthy even, to have an open relationship with both places. Canada might not be as cosmopolitan as the U.S. in some ways, but she still has much to teach America about social policies and general tolerance.

After all, they don't call America "Canada's bottom" for nothing.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

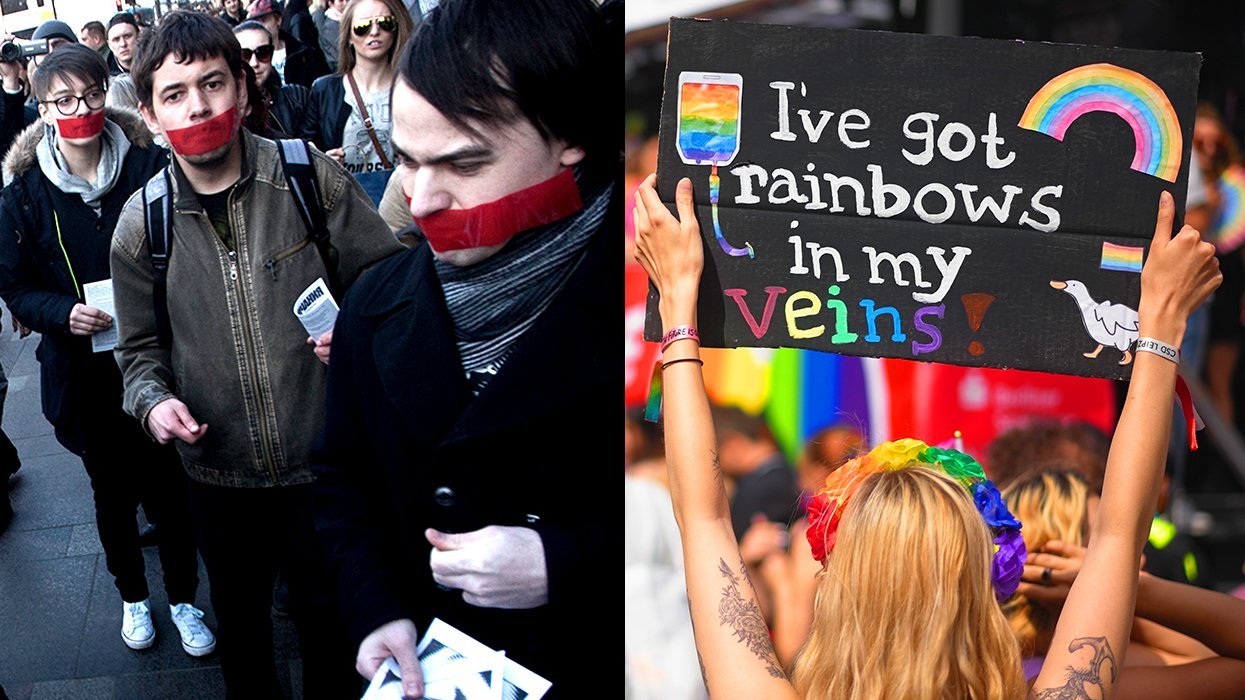

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

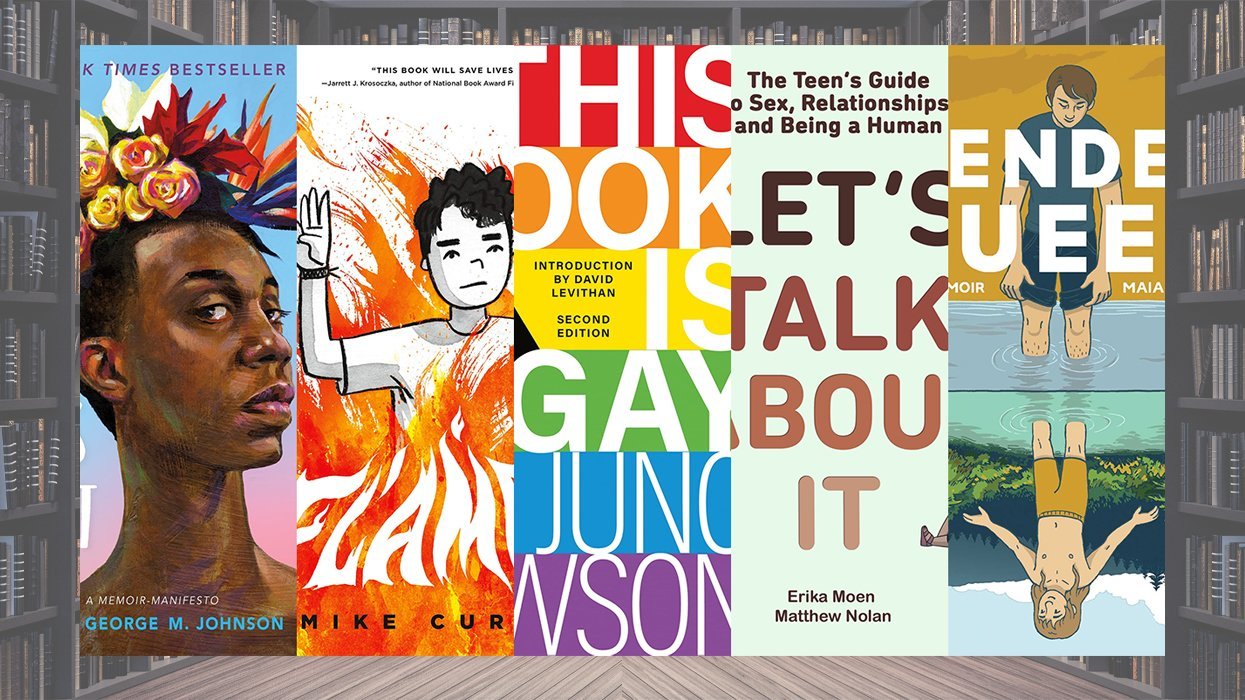

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM

Investigation launched after man screams homophobic slurs at queer couples on D.C. metro

April 13 2024 9:59 AM

Germany makes it easier to change gender and name on legal documents

April 12 2024 6:06 PM

A youth's call to action on this Day of NO Silence

April 12 2024 5:00 PM

Democrats introduce resolution in support of LGBTQ+ youth

April 12 2024 4:35 PM

Colton Underwood is hoping to create a gay reality TV dating show

April 12 2024 4:28 PM

Idaho closes legislative session with a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ laws

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedElevating pet care with TrueBlue’s all-natural ingredients

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Watch Jimmy Kimmel's hilarious LGBTQ+ campaign video: 'You can't spell Biden without Bi'

April 12 2024 12:00 PM

Pride

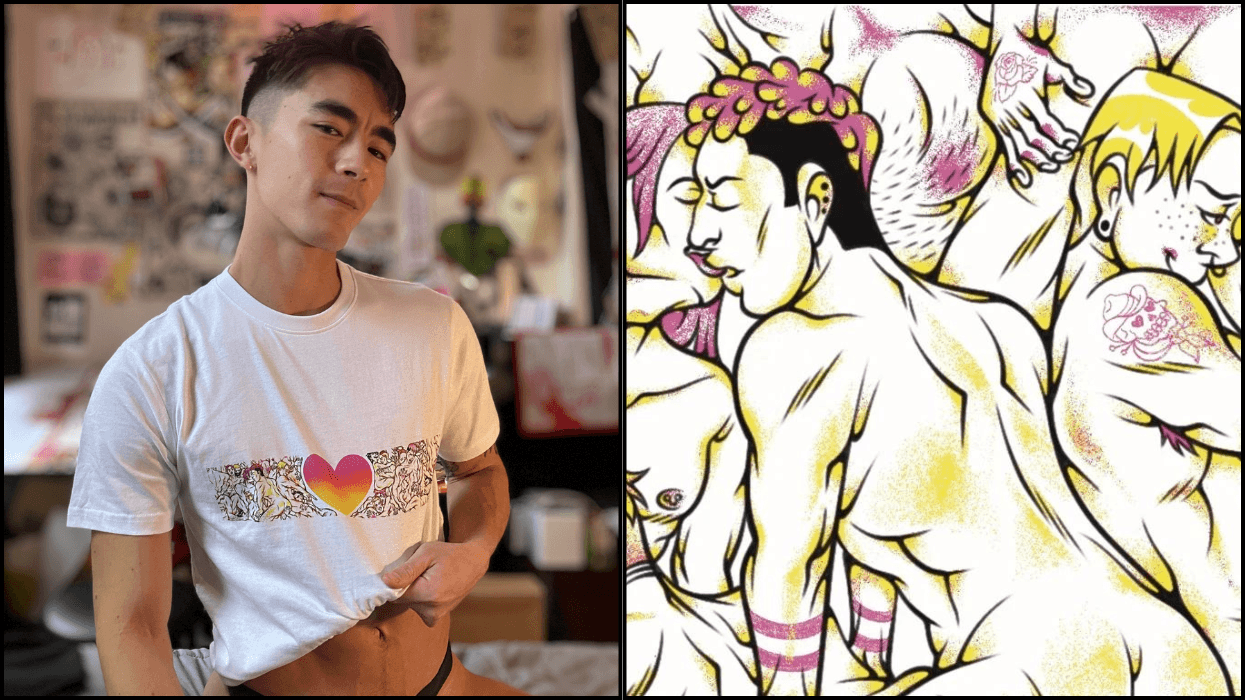

Yahoo FeedCreating erotic art and advocacy with adult entertainer Cody Silver (EXCLUSIVE)

April 12 2024 11:39 AM

How I navigated through religious trauma

April 12 2024 11:00 AM