In Washington, D.C. -- just steps from the White House, the pristine monuments, and the tony residences of some of the world's most powerful people -- one can also find the Check It gang.

Begun in 2005 by a group of bullied ninth-graders, the so-called gay gang has grown to over 200 LGBT young people of color, some of whom are as young as 14 years old. Many wear lipstick, designer clothes, and stilettos, and carry Louis Vuitton bags. At least one carries a pink taser. In the shadow of the Verizon Center, they dance and defy expectations of what gang members should look like and be.

For many, the Check It is a family, a place of support and protection in a world that can be cruel and unaccepting. For others, the group is a menace to society, a source of crime and violence that is anything but glamorous.

Dana Flor, the codirector of a new documentary, Check It, which follows members of this group, has another word to describe it.

"It's shameful," she told The Advocate. "The situation is shameful. And that's part of the purpose of the movie, is to show we should all be ashamed that this is happening."

The documentary, which Flor directed alongside Toby Oppenheimer, follows several African-American young people with ties to Check It, among them Skittles, Tray, Day Day, Star, and Alton. It also illustrates how the gang is a source of both pride and shame.

The pride, as one member stated, comes from defying the expectation that "gays are weak and that we can't fight." In a world in which the murder rate of trans women in the United States, particularly in the greater D.C. area, is skyrocketing, the strength that comes with a group like Check It becomes a necessary shield against those who would do physical harm to its members.

The shame is multifold. First, the gang is not always a force for good. "When somebody is bullied, they become bullies in some form," as stated in the documentary. Numerous witnesses testify as to how some of the Check It gang members intimidate others, brawl, and commit crimes and violence.

But the true crime is that the gang has to exist at all. Many of its members are homeless, jobless, and forced to steal and do sex work in order to survive. Many, as one of their mentors, Ron "Mo" Moten, told The Advocate, "use drugs as a self-defense mechanism. It's more to heal their pain ... to take the memory away."

Statistically, LGBT youth are far likelier to experience bullying and harassment at school than their straight peers. Because of this reality, they are also likelier to miss school and attempt suicide. But this is only the tip of the iceberg for Check It's members, many of whom also battle health issues like skyrocketing HIV rates. According to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at least half of gay and bisexual black men will contract HIV in their lifetimes. Trans women are nearly 50 times as likely to contract HIV than straight people. That's not to mention the violence in the streets of D.C., which claims dozens of lives each year, as well as the systemic injustices endured by all African-Americans.

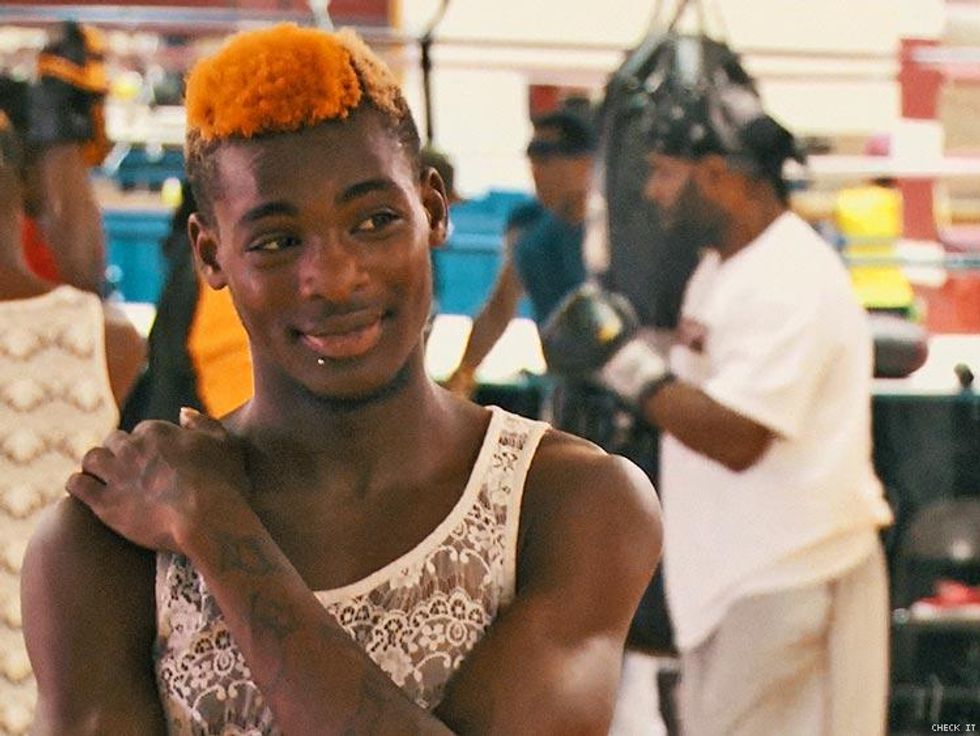

Skittles (Photo by Toby Oppenheimer)

Check It puts faces on these statistics, which many might hear or read about, but they seldom see the reality on the ground. It also shows how few resources are reaching these vulnerable young people, and how precious little support they have from those who should be protecting them.

The documentary has many heartbreaking scenes of this neglect. Tray, sitting in an alley, calls the police to report a rape, only to have pleas discounted, rerouted, and ignored. A sex worker promises to quit the streets once they reach 11th or 12th grade. Another youth lies barely conscious on the sidewalk. Illuminated by police cars' lights, he is encircled by Check It members who are angry and confused, and it is unclear if the situation will end in assistance or violence.

However, the documentary is not all doom and gloom. It is hopeful in its portrayal of how various people -- including Mo, a longtime community outreach worker -- are helping Check It members into careers that will save them from the streets.

Much of the film centers on a fashion camp, in which young people are trained, in the style of Project Runway, to design clothes, style models, and produce a fashion show. A capstone event at a hotel showcased this work. In the end, five participants won an opportunity to assist professionals during New York Fashion Week.

In essence, this camp is a lifeline, which offers job skills and experience that could lead to careers for several of these young people. It also produces several humorous moments, such as when one of the winners, Dennis, upon learning that cigarettes in New York City cost over $15, reacts by stating, "Y'all guys go jump off a bridge!"

What wasn't funny, however, was the notable absence of major LGBT organizations from the documentary. At its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival last month, Mo told the audience how he felt the LGBT community at large was failing these young people. He repeated these sentiments to The Advocate in an interview alongside Check It's subjects.

There have been "no gay advocates," he observed, no mentors who "step up and say, 'Look, I got these younguns.' You know what I'm saying? I haven't seen it. And it should be that. It should be people who come in, and mentor, and [say], 'I got you under my wing.'"

"Or give 'em a job," suggested Flor.

When asked by The Advocate if they felt supported by Washington, D.C.'s LGBT groups, among them the Human Rights Campaign, the young people in the documentary unanimously said, "No."

The Advocate conveyed this response to the HRC, which forwarded a comprehensive list of initiatives and resources the group has devoted to LGBT youth. This list includes its All Families-All Children program, which works with foster-care agencies to provide services to this demographic and trains child welfare professionals. There are also coming-out guides, internship and fellowship opportunities, social media campaigns, and advocacy for legislation like the Equality Act.

Ellen Kahn, head of HRC Foundation's Children, Youth, and Families program, gave a message of support to the members of the Check It.

"We are working every day to improve the lives of LGBTQ young people, especially those facing the toughest challenges," Kahn stated. "I'd like to assure these young people that we're working in your schools, with your parents, health care providers, employers, and social services agencies to help build a safer, more supportive community around you. You deserve to be loved, respected, and supported, and we are committed to helping make that happen."

Alton (Photo by Toby Oppenheimer)

However, these ambitious initiatives are little felt by Check It's members on the ground. And the challenges they face are perhaps larger than LGBT groups alone can address. For instance, the homelessness rates in Washington D.C. have exploded in the past year, especially among young people and families, and LGBT youth are dispropriately represented in this population.

Yet, citing his experience trying to promote the fashion event and its worthy cause, only to encounter closed doors, Mo expressed disappointment with what he has observed as a local lack of interest in the fates of Check It's members.

"There's programs in D.C., but there's nothing customized for this particular group," Mo said. "What happens to them is what happened with straight people. There's a certain group that nobody wants to touch."

The reason, said Mo and the filmmakers, is the violence that occasionally erupts among members of this group. "Nobody wants to touch it," Flor repeated. "People really did say that: Fantastic movie. Loved it. Loved the kids. Great characters. Love it, can't touch it."

"Which is crazy, but it's just the reality," Oppenheimer said, stressing, "Violence is a symptom" of the problem.

"Hurt people hurt people, and healed people heal people," Mo said. "And you've got all of these young people who have been hurt so much, and people let them down."

It's a vicious cycle, and job opportunities and mentorships are just a few of the ways people who identify as LGBT or otherwise can help break it. Mo praised the work of Courtney Snowden, D.C.'s deputy mayor, for helming a mental health call agency that has employed several of these young people. But it's not enough. Many of these opportunites, which are targeted to those in their teens and early 20s, dry up for members like Star who age out of the program.

If nothing changes, many of these young people will die. In respose to this crisis, organizations and lawmakers can focus on systemic issues like homelessness and access to health care for LGBT people and communities of color, with specific outreach initiatives for youth. They can also allocate resources to build physical spaces, like homeless shelters, to keep these kids out of the cold.

"Where's the shelters?" questioned Day Day. "When are people going to take care of the real problems and stop trying to cover up things? You built schools, basketball and football stadiums, and all this, but you got a lot of teens that's from the ages of 12 to 18 that's homeless, don't have nowhere to go."

Of course, the act of paying attention and caring is a crucial first step. The White House made a blunder in 2015, when it hosted the first-ever screenings of transgender productions like The Danish Girl and Transparent but neglected to invite trans actress Mya Taylor to participate in the discussion. Her indie film, Tangerine, portrayed the lives of sex workers of color in Los Angeles, and Taylor, a former sex worker herself, recently told The Advocate how the event was a missed opportunity to address these issues.

However, the existence of the Check It documentary it itself a reason for hope. Flor and Oppenheimer -- on the heels of finishing a documentary in D.C. about its former mayor, Marion Barry -- were first introduced to the Check It gang by Mo in 2012, while exploring another documentary subject, go-go music.

"I've got a really amazing group of kids that you have to meet," he told them. After a meeting at Denny's, they signed on to the project and have been largely self-funded since. A crowdsourcing campaign, launched last year, met the fundraising goal required to complete production -- over $60,000, a sizable show of monetary support.

The project has also received celebrity interest. Its production company, Olive Productions, is helmed by Steve Buscemi and Stanley Tucci. Blondie's Debbie Harry was at the sold-out Tribeca premiere. There, the crowd's concern and enthusiasm for the documentary inspired its subjects, who were also in attendance.

"It shows that we have a lot of people who want to support us," Tray said. "So that makes me feel like there's still work to be done, but we are the people who can make it happen."

And for their mentor Mo, this change won't come soon enough.

"If we don't set something up, you're going to see more Check Its throughout America," he said. "And people can turn their head, and act like a lot of people I've seen in the LGBT community, who don't want to touch them, or people like them. But it's gonna spread like a cancer, because the root causes [persist]."

There "needs to be some change, before we look up and all our youth is gone," he concluded.

Watch the trailer for Check It below.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.