Andry Hernández Romero did everything right.

Keep up with the latest in LGBTQ+ news and politics. Sign up for The Advocate's email newsletter.

When he crossed into the United States from Mexico at the San Diego border legally in the fall of 2024, he didn’t hide. He turned himself in and requested asylum, the legal process designed to protect people fleeing persecution. He had fled Venezuela because he was a target due to his sexual orientation and his opposition to the country’s authoritarian government. In the months following a disputed 2024 election, the Maduro regime intensified its crackdown on dissent, with LGBTQ+ people among the most heavily targeted. Human rights groups have documented illegal searches, arbitrary arrests, and the revocation of passports, all tactics used to silence queer voices.

Related: Bad Wisconsin cop’s tattoo claim helped deport gay asylum-seeker to Salvadoran prison hellscape: report

Hernández Romero showed up for a U.S. government-issued appointment. He passed the “credible fear” interview, the initial screening to determine whether someone qualifies for asylum. He had no criminal record.

He thought he was safe. For months, he remained in U.S. custody, never once setting foot outside detention. After entering the country through a CBP One appointment, the legal process the U.S. government required at the time, Hernández Romero was sent to Otay Mesa Detention Center, a for-profit immigration jail near San Diego.

Then, just before his hearing, the 32-year-old vanished.

Related: Gay asylum-seeker's lawyer worries for the makeup artist's safety in Salvadoran ‘hellhole’ prison

On March 15, with no prior notice to his lawyer or family, Hernández Romero was deported in the dead of night. ICE officials accused him of having gang affiliations based on small crown tattoos on his wrists with the words “mom” and “dad.” The accusation originated in a report signed by a former Wisconsin police officer with a record of misconduct who now works as a private ICE contractor. The ex-cop, who had no formal gang training, reportedly flagged the tattoos as evidence of membership in the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua. There was no evidence. No hearing. No warning.

Under a wartime statute dusted off and reactivated by President Donald Trump in his second term, ICE officials didn’t need any. The Alien Enemies Act, first passed in 1798, allows the federal government to detain or deport noncitizens from countries it deems hostile during wartime. The last major use of the Alien Enemies Act came during World War II, when the U.S. government used it to arrest, intern, and surveil thousands of immigrants from Japan, Germany, and Italy, many of whom were longtime U.S. residents taken from their homes without charges or hearings. When Trump designated Venezuela as a hostile state, hundreds of Venezuelan men, including Hernández Romero, were deported without due process. Legal scholars warned that the move echoed other Trump-era expansions of executive immigration power, but the administration pressed forward.

Hernández Romero was flown to El Salvador, a country where he had never set foot, and handed over to the Salvadoran military. Within hours, he was locked inside the Terrorism Confinement Center, or CECOT. The detention complex, a massive concrete compound with guards in black balaclavas, has drawn comparisons to a concentration camp. Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele boasts about the prison in viral videos. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have warned of a pattern of inhumane conditions, arbitrary detentions, and torture.

Related: Gay Venezuelan asylum-seeker ‘disappeared’ to Salvadoran mega-prison under Trump order, Maddow reveals

Guards parade inmates in shackles. Cells are flooded with bright lights, beds are stacked metal slabs. There are no mattresses or pillows. Absolute silence is demanded. Abuse is rampant, according to the few who have come out alive.

After his release in July, the bruises on Hernández Romero’s body were healing, but the trauma had burrowed deep.

“I was forced to perform oral sex on an officer,” he said in a televised interview with a government-aligned television program in Venezuela. “Three officers passed batons over my private parts. That was too devastating. It was my integrity as a human being, as a person [of the LGBTQ community], that [brought me to my lowest point].”

What happened to Hernández Romero wasn’t a bureaucratic error. It was policy. What happened to get him and others released from hell on earth wasn’t a rescue mission. It was a movement.

The tweet that sparked a movement

On the night Hernández Romero disappeared, Lindsay Toczylowski clicked on X, now Twitter, for the first time in a while.

A seasoned immigration attorney and cofounder of Immigrant Defenders Law Center, or ImmDef, Toczylowski had grown disillusioned with social media’s performative outrage cycle. But this was different.

It was Saturday, March 15. ICE had deported her client without notifying her office. His name was missing from the federal detainee locator. Their only clue was a hunch: he could be in El Salvador.

That night, she opened her laptop and started typing.

“Returning to X to shine a light on what the Alien Enemies Act looks like IRL,” she wrote. “Our @ImmDef client fled Venezuela last year & came to US to seek asylum. He has a strong claim. He was detained at entry because ICE alleged his tattoos are gang related. They are absolutely not.

”That initial classification, despite having never stepped foot in the U.S. outside of detention, exposed Hernández Romero to the Trump administration’s heavy-handed immigration policies.

In a seven-post thread that quickly gained traction, she explained how her client had complied with every legal step required, and then disappeared.

Related: Andry Hernández Romero’s family desperate for word on gay asylum-seeker who Trump vanished over 100 days ago

She hadn’t planned to go public. Most attorneys in her position protect clients’ privacy, especially LGBTQ+ asylum seekers from anti-LGBTQ+ regimes. But this wasn’t a typical case.

“Honestly, there are a lot of things that happen as a deportation defense lawyer that seem incredibly unjust,” she told The Advocate in July, after Hernández Romero’s release, but before she could speak with her client. “But the day that Andry disappeared, it felt different. It felt really desperate and scary.”

The reaction was immediate.

Media megaphone meets moment

Within days, CBS News published a leaked deportation manifest with Hernández Romero’s name on it. Lawyers, activists, journalists, and concerned citizens flooded ImmDef’s inbox asking how to help. Human rights organizations began paying attention. MSNBC star anchor Rachel Maddow aired a segment on The Rachel Maddow Show, featuring Toczylowski discussing Hernández Romero’s case, giving him a name and showing photos of him, his face softly contoured with makeup, holding brushes, smiling. She revealed that he was a gay makeup artist, actor, and pageant participant. He looked nothing like the criminal ICE implied.

Related: Deported gay makeup artist cried for mother in prison, photojournalist says

Then came the bombshell: 60 Minutes aired an exposé on April 6. In the segment, Time photojournalist Philip Holsinger recounted hearing a man cry, “I’m not a gang member. I’m gay. I’m a stylist,” as CECOT guards slapped him and shaved his head.

On April 22, The Advocate published a detailed interview with Toczylowski, in which she described the emotional toll of the case and the horrifying conditions her client faced inside CECOT. She warned that Andry’s deportation was not a clerical mistake but a deliberate act of cruelty, calling it “as bad as it gets.”

As the news of Hernández Romero spread, it caught the attention of Crooked Media.

The liberal media company, best known for Pod Save America, had long used its platform to spotlight underreported injustices. But this one struck a nerve. By this time, another man, a Maryland father from El Salvador named Kilmar Abrego Garcia, had been deported to CECOT in error, according to the Trump administration, and that case had garnered national outrage.

Cofounder Tommy Vietor confirmed details with ImmDef and booked Toczylowski on the April 10 podcast. The interview reached a new audience.

Related: Hundreds rallying at Supreme Court demand Trump return disappeared gay asylum-seeker Andry Hernández Romero

Crooked Media didn’t stop at the podcast appearance.

In June, during WorldPride in Washington, D.C., Crooked Media partnered with The Bulwark, a center-right publication led by anti-Trump conservatives, to cohost a live show at the Lincoln Theatre. Crooked Media's gay cofounder Jon Lovett, The Bulwark’s contributor and host Tim Miller, and publisher Sarah Longwell, both also gay, headlined a show that mixed political outrage with comic relief.

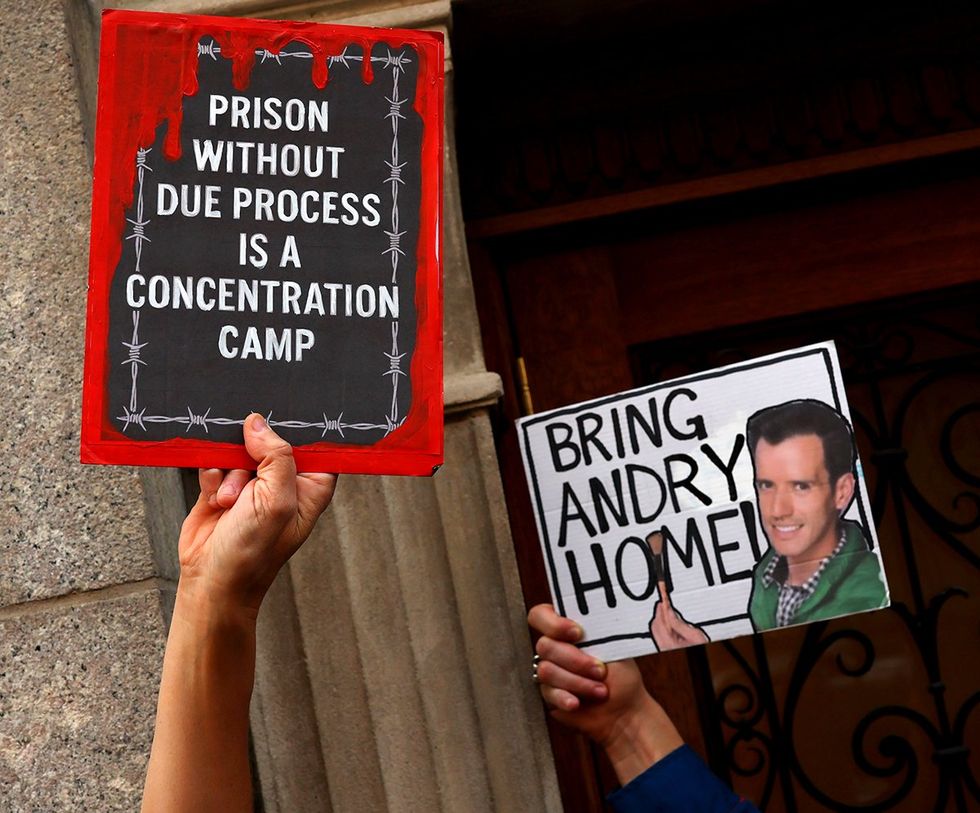

Earlier in the day, the podcasters joined the Human Rights Campaign at the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court, where hundreds gathered to demand “Free Andry!”

It was strategic.

“Our bread and butter is taking opportunities where people are, where we’ve already captured their attention, or something else has,” Shaniqua McClendon, Crooked Media’s vice president of politics, who leads the group’s civic engagement arm, Vote Save America, said in an interview with The Advocate.

“This is the worst thing that Trump has done, which is a very competitive category,” Miller told The Advocate in May. “There are certain things we can rant and yell about that won’t change anything until the next election. But this case? They need to feel pressured to act.”

Related: Jon Lovett and Tim Miller team up to ‘raise hell’ over gay asylum-seeker vanished to El Salvador by Trump

The idea came to him in the shower, he said, after stewing in rage and grief.

The show raised $20,000 for ImmDef. They displayed Hernández Romero’s image on screen and called the audience to act. “We gathered for a sad reason,” said McClendon. “But anyone who was at the show knows it was a really funny show. You had three queer hosts up there. They brought a lot of attention to the issue, but it was also funny and engaging, and that’s just what Crooked does.”

As the English-language media spotlight intensified, another front was quietly building power.

The power of visibility

While outlets like Crooked Media and MSNBC pushed the story across progressive circles in the U.S., GLAAD focused on Latin American and Spanish-language audiences, many of whom understood the word “disappeared” in a way most Americans do not.

Monica Trasandes, GLAAD’s director of Spanish-language and Latinx media, knew the weight of the word. She was born in Uruguay and fled during the rise of military dictatorships. “The word ‘disappeared’ is a huge part of Latin American history,” Trasandes told The Advocate. “So seeing that start to happen here is frightening. I know where it leads.”

Related: Coalition of 52 Democrats push for proof of life for deported gay asylum-seeker Andry Hernández Romero

In Latin America, the word desaparecido doesn’t imply a bureaucratic oversight. It means something far darker. During the 1970s and ’80s, U.S.-backed military regimes across the region, including in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Guatemala, and El Salvador, abducted tens of thousands of students, labor organizers, queer people, and political dissidents. These people, detenidos desaparecidos, weren’t just arrested. They were disappeared. Taken in the dead of night, held in clandestine prisons, tortured, killed, and buried in unmarked graves, if at all.

In Argentina alone, human rights groups estimate that 30,000 people were disappeared under the junta. Families were left with no answers, no justice, no graves to visit. The tactic wasn’t simply to remove someone. It was to erase them entirely, as if they had never existed. That history lingers heavily in Latin American memory, which is why, Trasandes said, Hernández Romero’s case — one man disappeared without notice or trial — triggered such outrage among Spanish-speaking audiences. They recognized the pattern.

Related: Gay makeup artist Andry Hernández Romero describes horrific sexual & physical abuse at CECOT in El Salvador

GLAAD acted quickly. The group monitored Spanish-language press, translated interviews, created viral graphics, and amplified the reach of outlets like Univision and Telemundo to spread the story.

“He had crown tattoos on his wrists that said ‘mom’ and ‘dad,’” Trasandes said. “That is not a gang member. It’s ridiculous. The cruelty, the shamelessness, the un-American-ness of it all, it outraged people. And people acted.”

Hernández Romero’s image soon appeared on Pride floats and at parades. At Queens Pride in New York City, San Diego Pride, Rhode Island Pride, and elsewhere, he was named an honorary grand marshal. His image was everywhere from WorldPride in Washington, D.C. to tiny Fredericksburg Pride in Virginia.

GLAAD President and CEO Sarah Kate Ellis called Hernández Romero’s treatment a “severe human rights violation” and emphasized that his case should not be forgotten. “Despite following the asylum-seeking process, Andry Hernández Romero was still wrongfully detained like countless others,” she said.

At the end of June, word came that Hernández Romero’s family had still not heard anything about his well-being and continued to agonize over his whereabouts.

The ACLU lawsuit

As the public campaign gained steam, the American Civil Liberties Union brought a legal challenge to the Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelan asylum seekers to El Salvador. The lawsuit argued that the administration violated basic constitutional protections by denying individuals the right to notice, evidence, or a hearing.

Since then, federal courts have begun weighing in. At least four district courts have ruled that the Alien Enemies Act was unlawfully invoked, noting that the U.S. is not at war with Venezuela and that wartime powers cannot be used to justify mass deportations based on unproven gang allegations.

Related: Democratic lawmakers fly to El Salvador and demand action on gay man Trump sent to CECOT prison

The U.S. Supreme Court weighed in, too. In May, it reaffirmed that noncitizens targeted under the AEA are entitled to due process, including notice and the opportunity to challenge their removal in court. Just 24 hours’ notice without guidance, the Court said, likely doesn’t meet that standard.

Lower courts also questioned the government’s claim that the men held in CECOT were no longer under U.S. control. While one judge accepted a State Department affidavit to that effect, he warned the government against misleading the court and noted that the gang allegations ranged from “flimsy” to “frivolous.”

The legal challenges are ongoing. But across the judiciary, a consensus was emerging: The Trump administration cannot use a centuries-old wartime statute to disappear people without constitutional safeguards.

Building political pressure

As protests grew louder, lawmakers began to act. Among the first was Rep. Robert Garcia of California, the first out gay immigrant elected to Congress. He traveled to El Salvador to see what was happening firsthand.

“When I went to El Salvador in April, I met the [U.S.] ambassador, and I mentioned Andry to the ambassador then. This was the first time the ambassador had heard about his case,” Garcia told The Advocate.

Garcia’s office coordinated with ImmDef to try to confirm that Hernández Romero was alive. At the time, there were no letters. No calls. Just silence. In the weeks that followed, Garcia and members of the Congressional Equality Caucus, a group of LGBTQ+ and ally lawmakers, sent formal letters to the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department demanding information and a review of ICE’s use of the Alien Enemies Act.

Related: Democratic lawmakers fly to El Salvador and demand action on gay man Trump sent to CECOT prison

At one House Oversight Committee hearing in May, Garcia pleaded with Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem to provide proof of life to Hernández Romero’s mom. She refused.

“We just kept banging the drum in the media to get folks to pay attention to him,” Garcia said. He also raised the issue during the Crooked-Bulwark live show. “Obviously, being a gay immigrant very much gave me a perspective that was different,” he said. “I really felt for him.”

Gay New York U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres donated $1,000 of campaign funds to Hernández Romero’s lawyers.

Related: New York’s Ritchie Torres donates to Andry Hernández Romero fund demanding freedom for gay asylum-seeker

Jonathan Lovitz, senior vice president of campaigns and communications at the Human Rights Campaign, helped raise awareness of Romero’s case nationally. “This wasn’t just a political error. It was a humanitarian crisis,” Lovitz told The Advocate. “And we treated it like one.”

HRC gathered more than 14,000 petition signatures, worked with Pride organizers to include Hernández Romero’s image in programs, and activated state-level staff to elevate his case in media and speeches.

The release and the road ahead

After 125 days inside CECOT, Hernández Romero was released and returned to Venezuela on July 18. But it wasn’t justice. It wasn’t asylum. It wasn’t even safety. His release was the result of a secretive prisoner swap, not a legal victory, and the U.S. government has offered no acknowledgment that anything went wrong. Ultimately, advocates said, keeping these men in captivity became untenable.

Behind the scenes, the Trump administration had been negotiating a structured exchange with the Venezuelan government to bring back American hostages and political prisoners. Secretary of State Marco Rubio had led formal diplomatic talks. But those negotiations were derailed for weeks, according to the New York Times, after Ric Grenell, Trump’s out special projects envoy operating outside official channels, attempted to strike a side deal with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Grenell floated a separate proposal involving Chevron oil rights, undercutting Rubio’s efforts and stalling the release of detainees held at CECOT.

Related: Andry Hernández Romero, gay asylum seeker disappeared by Trump, part of prisoner swap

The detainees, including Hernández Romero, were freed, but not allowed to return to the United States. Instead, they were deported back to Venezuela, the very country Hernández Romero had fled in fear for his life as a gay man to begin with.

On The Bulwark podcast that night, Miller described the diplomatic arrangement not as a rescue, but as a “hostage swap,” drawing a sharp comparison to Russia’s detention of WNBA star Brittney Griner, who was held in captivity for nearly a year in 2022 on fabricated charges. She was eventually released in a high-profile exchange for a convicted Russian arms dealer. "They kidnap random civilians, wrongfully detain them, and then use them for a prisoner exchange,” Miller said. “That’s what this was.”

Miller accused the U.S. government of misleading the public about its role. Trump administration officials had told judges that the detained men at CECOT were beyond the jurisdiction of the U.S. That assertion was hard to stomach since Trump had paid El Salvador to house the migrants. "They have been lying this whole time,” he said. “The United States is and has been in control here.”

Without much fanfare, the men that the Trump administration previously called the “worst of the worst” were free.

Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin did not respond to The Advocate’s request for comment.

What Hernández Romero knows, for now, is that he survived. The relief and stress on his face were evident as the first photos of his reunion with family were published.

“As far as we know, being held incommunicado, he has no idea,” Toczyloswski told The Advocate. “He has no idea that his story was on 60 Minutes. He has no idea that millions of people around the world were writing letters or showing up to rallies with his name on posters.”

Related: Gay asylum seeker Andry Hernández Romero remains in danger, advocates warn

Ellis noted that even with Hernández Romero’s release, “[his] safety is not guaranteed,” and urged continued public pressure. “Every person, organization, and media outlet who shared Andry’s story, attended a rally, and spoke with friends and family about his case showed that change is possible when we work together.”

But for the coalition that rose around him, the fight isn’t over. The Alien Enemies Act remains on the books. Deportations continue. U.S. officials have not admitted wrongdoing. “This was never about just one person,” Lovitz said. “It was about what kind of country we are. And whether we’re going to be complicit when vulnerable people are targeted for cruelty.”

Hernández Romero’s legal team is still evaluating his options, including whether another country, perhaps one in Europe, would take his asylum case. Toczylowski said she doesn’t think he would be safe in the U.S. under the current administration.

Why Andry’s story broke through

Not every human rights violation sparks such a movement. But Maddow believes Hernández Romero’s case did because it exposed a tactic as old as state violence: erasing someone’s humanity to justify their persecution.

“People respond to other human beings,” Maddow said in an interview with The Advocate in June. “And people who would oppress us try to make sure we never see the people being oppressed as human beings. The dehumanization and depersonalization of the targets of this kind of oppression is a tactic that they are trying, and that is failing.”

Related: Kristi Noem won’t say if gay asylum-seeker deported to El Salvador’s ‘hellhole’ prison is still alive

Maddow said the Trump administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act depended on treating people as abstractions, as potential threats, not as individuals. When the government takes due process away, Maddow argued, it often insists that the person harmed didn’t deserve it, that if people only knew more, they’d agree the person was dangerous or unworthy. But when the target is visible and knowable, that tactic fails.

That’s what happened with Andry, she said. People didn’t see a faceless, nameless, violent criminal. They saw someone like them.

Hernández Romero’s case was impossible to abstract away. He was a gay makeup artist from Venezuela. He had a name. A photo. A story. People saw his face, saw him holding brushes, smiling. They learned about the tattoos that said “mom” and “dad.” They read what happened to him inside CECOT.

Related: Rachel Maddow sees Americans’ active resistance as key to overcoming Donald Trump’s strongman game

Once the story became personal, outrage followed. Maddow thinks that the American resistance movement against the Trump administration is the most important story of the current time.

“Anywhere where we’ve got sort of personalized details about the people who they are mistreating in this way, you are seeing the American people stand up and say, I don’t want you treating that person that way,” Maddow said.

She pointed to other examples: a waitress in Missouri whose detention drew national attention after a New York Times profile; Mohsen Madawi, a Columbia University student whose neighbors helped secure his release; and Ramesha Ozturk, a Tufts University graduate student whose abduction was caught on a Ring camera. In each case, people didn’t just respond to the policy; they responded to the person.

Andry’s case, she said, exemplified how that emotional connection works. “Due process is something that is A, boring, and B, something that is absolutely the iron substructure of the rule of law,” Maddow said. “It’s the basis for every legal thing, every governed thing, every bit of fairness in the world.”

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.