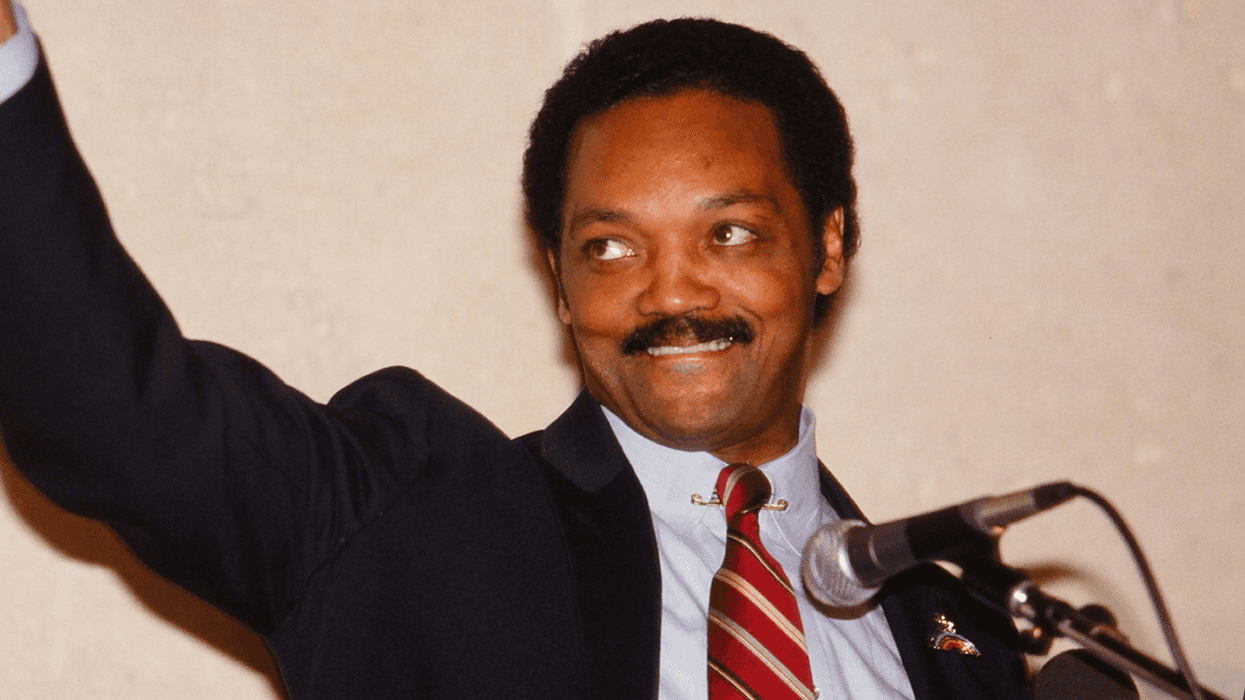

Doctors and AIDS activists in Africa are worried governments may halt use of an HIV antiretroviral drug that has protected thousands of babies from HIV infection in reaction to new concerns about the drug's testing and effect on pregnant women. The Reverend Jesse Jackson is calling for a U.S. congressional investigation into a report that U.S. health officials were warned that research on nevirapine, sold in the United States as Viramune, was flawed. The warning was withheld from the White House weeks before President Bush announced a plan in 2002 to distribute the drug in Africa, the Associated Press reported this week. The AP report said that testing of nevirapine at Uganda's Mulago Hospital failed to meet international standards and that pregnant women who take the drug once to inhibit passing HIV to their babies may develop resistance to it that can limit the ability of drug therapies to combat the deadly disease. In calling for the investigation, Jackson demanded that nevirapine no longer be distributed in Africa. "This was not a thoughtful and reasonable decision, but a crime against humanity," he said Thursday in Chicago. "Research standards and drug quality that are unacceptable in the U.S. and other Western countries must never be pushed onto Africa." Saul Onyango, a medical officer involved in the testing, said African officials fear being denied use of the drug. "It's an issue affecting people's lives. A lot of damage has already been done and we need to do damage control," Onyango said. Francis Miiro, a key researcher, dismissed concerns about the testing as discrimination against African scientists and insisted the drug works safely. In South Africa, the Treatment Action Campaign, which lobbied for access to antiretroviral drugs in that country, warned that reopening debate about the Uganda study could frighten patients off their treatment, even though subsequent research has confirmed nevirapine is safe and effective. "I don't see a problem with nevirapine at all," said the group's leader, Zackie Achmat, who found out he was HIV-positive in 1990. "I use it twice daily." Doctors working in the public health system, which serves the vast majority of South Africans, have privately expressed fears they will be pressured to stop using single-dose nevirapine for pregnant women before alternatives are available. "I'm of the view that we should use nevirapine until a better situation can be created," said Ashraf Coovadia, head of the pediatric HIV clinic at Johannesburg's Coronation Mother and Child Hospital. "To halt the program would cause damage to what we have already achieved." In July, a South African regulator recommended a halt to the single-dose nevirapine regime for pregnant women, saying a "cocktail" of drugs should be used instead even though such drugs are expensive and available mostly in the United States and other wealthy nations. On Wednesday, the South African health department said U.S. concerns about the quality of nevirapine research in Uganda supported its cautious attitude to the drug and it was reviewing its guidelines on mother-to-child HIV transmission. Spokesman Sibani Mngadi said the drug is still distributed by hospitals for now. "It is part of a public health program which cannot be stopped just because this research is continuing," Mngadi said. Studies show that a single dose of nevirapine to an infected woman during labor and another dose to her newborn baby can reduce the chances of HIV transmission by up to 50%. Nevirapine can cause rashes, liver toxicity, and even death in some patients who use the drug on a daily basis to treat HIV, though no serious reactions have been reported after a single dose. But a South African study found that 39% of HIV-infected women who get a single dose of nevirapine go on to harbor virus that is resistant to the drug. In a letter obtained by the AP, U.S. health officials told Uganda's government in July 2002 that the research had violated federal patient safety rules. The memos show U.S. officials knew about the problems as early as January 2002 but chose not to tell President Bush before he authorized shipping the drug to Africa later as part of a $500 million initiative. (AP)

Search

AI Powered

Human content,

AI powered search.

Latest Stories

Stay up to date with the latest in LGBTQ+ news with The Advocate’s email newsletter, in your inbox five days a week.

@ 2026 Equal Entertainment LLC.

All rights reserved

All rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

The Latest

Support Independent Journalism

LGBTQ+ stories deserve to betold.

Your membership powers The Advocate's original reporting—stories that inform, protect, and celebrate our community.

Become a Member

FOR AS LITTLE AS $5. CANCEL ANYTIME.

More For You

Most Popular

@ 2026 Equal Entertainment LLC. All Rights reserved