Drug-resistant

staph infections that have made headlines in recent weeks

come from what the nation's top doctor calls ''the cockroach

of bacteria'' -- a bad germ that can lurk in lots of

places but not one that should trigger panic.

''This isn't

something just floating around in the air,'' Dr. Julie

Gerberding, head of the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, told members of Congress on Wednesday.

It takes close

contact -- things like sharing towels and razors, or

rolling on the wrestling mat or football field with open

scrapes, or not bandaging cuts -- to become infected

with the staph germ called MRSA outside of a hospital,

she said. But MRSA is preventable largely by

common-sense hygiene, Gerberding stressed.

''Soap and water

is the cheapest intervention we have, and it's one of

the most effective,'' she told a hearing of the House

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

At issue is

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a

form of the incredibly common staph family of germs. About

one in every three people carries staph aureus in their

noses. In about 1 million people, the type they carry

is MRSA.

''I like to think

of it as the cockroach of bacteria,'' Gerberding said,

pointing out MRSA's ability to live on various surfaces and

spread by catching a ride on an unwashed hand.

Over time, germs

evolve to withstand treatment. Most staph is no longer

treatable by the granddaddy of antibiotics, penicillin. By

the 1960s, staph also began developing resistance to a

second antibiotic, methicillin.

So MRSA is not a

new problem. What is new is public anxiety about it.

MRSA mostly

causes skin infections such as boils and abscesses. But it

can sometimes spread to cause life-threatening blood

infections. Last month the CDC reported the first

national estimate of serious MRSA infections -- 94,000

a year. It's not clear how many people die, but one

estimate put the MRSA death toll at more than 18,000,

slightly higher than U.S. deaths from AIDS.

There are two

distinct strains of MRSA, a type spread in hospitals and

other health facilities and a genetically different type

spread in communities. The vast majority of victims

are hospital patients; only 14% of serious MRSA

infections are the kind spread in the community.

But the CDC's

report coincided with the death of a 17-year-old Virginia

high school student, prompting a spate of reports of MRSA

infections in schools. That prompted lawmakers to

pepper Gerberding with questions Wednesday:

-Should schools

close for cleaning if a student gets MRSA? That's not

medically necessary, Gerberding said. Bleach and a list of

other germicides can be used in routine cleaning of

areas and equipment where bacteria cluster.

''There's no need

to go in and disinfect a whole school because that

isn't how this organism is transmitted,'' she said.

-How worried

should parents be? Some 200 children a year will get serious

MRSA, and the vast majority will be treated successfully,

Gerberding said. Community-spread MRSA is still easily

treated by many other routine antibiotics. So wash and

bandage cuts and seek prompt medical care if they show

signs of infection.

Most outbreaks of

community-spread MRSA occur not in schools but in

prisons, where inmates share toiletries and lack or don't

use soap.

-Should every

patient entering a hospital be tested for MRSA, and

isolated if they harbor it? Some hospitals have begun that,

but current guidelines call for that step only if

hospitals fail to reduce MRSA infections by less

drastic means, Gerberding said.

Her concern:

''Patients in isolation get less care.'' Doctors and nurses

check on them less. They get more bed sores, opening the

body to other life-threatening germs.

There is a

biological conundrum: Hospital-based MRSA is more common and

vulnerable to fewer antibiotics than the strain spread in

communities, and already-ill patients are more likely

to die from it. Yet the community strain of MRSA may

be somewhat stronger, possibly explaining why

otherwise healthy people sometimes succumb.

It's a strain

called USA300, and if it penetrates the skin, it can cause

key immune cells -- white blood cells -- to explode, setting

off a chain reaction of inflammation, Gerberding

explained. This strain, unlike most hospital MRSA,

also produces a toxin known as PVL, and scientists are

furiously investigating its role.

New antibiotics

are important but won't solve MRSA or the myriad other

drug-resistant bacteria, she said.

Germs ''will

always be one step ahead of our drugstores,'' Gerberding

said. ''We have to get back to the basics'' -- wash your

hands and cover your cuts. (AP)

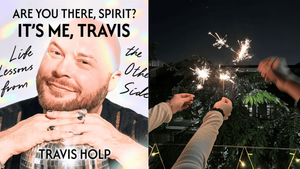

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes