In 1984, Don Babets and David Jean, a gay couple living in Boston, asked a friend to contact the Massachusetts Department of Social Services to inquire whether their sexual orientation rendered them ineligible to serve as foster parents. After officials assured their friend that it did not, the couple attended a six-week foster care training program. They were also visited at home several times by a social worker who interviewed them for hours on end.

For most individuals, approval by the social worker after a home visit would have led to their certification as foster parents. But because Don and David were a gay couple, their application was forwarded to the department's headquarters in downtown Boston for special review. After several months went by, and after Don called on a weekly basis inquiring about the application's status, DSS finally issued them foster parent licenses.

Don, who was 36 and worked as an investigator for the Boston Fair Housing Commission, and David, who was 32 and worked as a nursing home administrator, had met nine years earlier on a blind date as Don was finishing an eight-year stint with the army. The two men hoped to adopt children some day, but wanted to start with foster parenting as a way of proving to themselves, and to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, that they could be good parents.

In April 1985, DSS placed two brothers in Don and David's care; the older boy was 3 years old, the younger one 22 months. The boys' mother, who was going through difficult times but hoped to regain custody of her sons later that year, consented in writing to the state's placement of her children with the same-sex couple.

For Don and David, the first two weeks with the boys in their home were nothing less than blissful, as the two men happily adjusted their routines in order to care for the energetic toddlers. But one day, as David was giving a friend a ride in his car, he shared with her the news that the state had placed two foster children in their home. To David's surprise, the friend, who was the wife of a local community activist by the name of Ben Haith, advised him to be careful because some neighbors might not approve of children living with a gay couple.

Don and David had considered Ben Haith a friend; they had had him over for dinner several times, and David had given his daughter piano lessons. But a few days after David's conversation with Haith's wife, the community activist (who was planning on running for city council) contacted editors at the Boston Globe to complain that DSS had placed two young boys with a gay couple in his neighborhood.

The day after Haith contacted the newspaper, the Globe published a story on the foster care placement that focused mainly on the negative reactions by some of the gay couple's neighbors. Haith -- who later ended his efforts to seek elected office after being criticized for contacting the newspaper in order to bring attention to his political aspirations -- told the reporter that he was "completely opposed" to the placement and that he saw "it ultimately as a breakdown of the society and its values and morals." Other neighbors, after being told of the placement by the Globe's reporter, were also troubled. One person, described in the article as a "prominent lawyer," referred to the placement as "crazy," while another opined that "this situation falls below what is normal and healthy."

On the morning the story appeared, the DSS Commissioner called Don and David to assure them that the newspaper article would not lead the agency to take the children back. That commitment lasted about five hours. After Governor Michael Dukakis later that day ordered that authorities remove the boys, two government social workers showed up at the gay couple's doorstep -- TV cameras in tow -- and removed the crying and startled children from the home. The gay couple later explained in a statement that to see the children "leave us -- angry, confused, and in tears -- was one of the most difficult moments of our lives."

The state placed the children with a (heterosexual) foster mother living in a town outside of Boston. A few months later, the local District Attorney announced that he was investigating a social worker's report that the boys may have been sexually abused by someone else living in that home.

In 1973, the National Gay Task Force -- the organization cofounded by Bruce Voehler, a gay father profiled in Chapter 2 -- began working with private child welfare agencies to find foster placements for gay teenagers in the homes of gay men in New York City. By the time the New York Times published a story describing the program in May 1974, about 30 boys aged 12 to 17, who described "themselves as homosexuals and who [were] unwanted by or unable to adjust to youth homes," had been placed under the program's auspices.

In the early 1970s, gay organizations in several other cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis, worked with child welfare officials to place gay youth in the homes of gay men. There were also reported instances of foster care placements with lesbians, including one in Philadelphia in which "a 15-year-old transvestite male youth" was placed in the home of a lesbian couple.

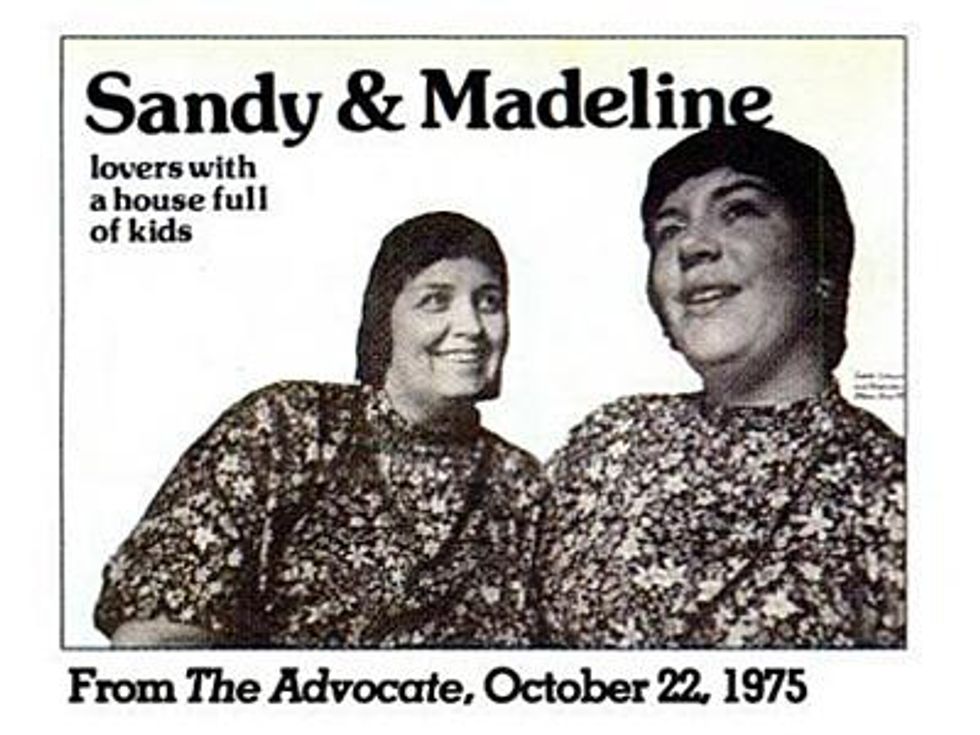

In 1974, The Advocate, reported that the publicity engendered by the custody case of Sandy Schuster and Madeleine Isaacson -- lesbian mothers profiled in Chapter 1 -- led several lesbians and gay men in Washington state to seek foster care licenses. The applications, in turn, produced a backlash as conservative activists urged the state to adopt a regulation prohibiting lesbians and gay men from serving as foster parents. One of those activists, who led an effort to gather more than 7,000 signatures in support of the regulation in a little over two weeks, claimed that gay people wanted to serve as foster parents to get state money to "support their lifestyle," as well as to make "contact with the youth of our country [in order to] drag them down to their sordid and sinful way of life."

Although a coalition of progressive child advocacy organizations successfully lobbied against the adoption of the proposed regulation, they could not prevent some judges from refusing to approve foster placements in gay households. This happened in Vancouver, Washington, in 1975, when child welfare authorities attempted to place a 16-year-old gay youth with a gay couple after the boy had spent two years living in institutions. When a judge found out about the proposed placement, he called for a hearing in his courtroom to consider the matter.

The administrators at the institution where the boy was living, as well as his social worker and a psychiatrist, testified that the child would benefit from the placement because the gay couple would be good foster parents and because there was no other family willing to take the openly gay boy into their home. In contrast, the local prosecutor's office, which opposed the placement, repeatedly suggested to the court that there was a real risk that the gay couple would "role-model [the] child into homosexuality" by, among other things, having sex in front of the boy.

Several weeks after the trial ended, the judge issued an opinion ordering that the teenager be placed in the custody of the county juvenile detention facility until another family -- a heterosexual one--could be found for him. The opinion explained that "it is not a proper function of the state to encourage and foster deviant behavior. If this [proposed placement] were followed to a logical extreme, state action could be rationalized in placing promiscuous girls with prostitutes or psychopathic youths with the mentally ill."

Despite judicial rulings such as this one, the placement of foster children in lesbian and gay households continued through the late 1970s and 1980s. Supporters of these placements received a considerable boost when the American Psychological Association in 1977, and the National Association of Social Workers a decade later, issued statements urging child welfare authorities not to discriminate on the basis of parents' sexual orientation in making foster care placement decisions.

In May 1985, Don Babets and David Jean, still reeling from the events of a week earlier when the state abruptly removed two foster children from their home, granted the Boston Globe an interview in which they criticized DSS for its actions. To the men, it made no sense for the agency to issue them foster care licenses after spending months evaluating their application only to then remove the children "hours after the media learned of the placement." This suggested to the couple that the decision to take the boys away was driven by politics rather than by what was best for the children.

Ten days later, the Massachusetts House of Representatives approved a bill, by a vote of 112 to 28, that would ban the placement of foster children with lesbians and gay men. The provision stated that "a homosexual preference shall be considered a threat to the psychological and physical well-being of a child." The bill was sent to the state senate, which never approved it because DSS soon announced that it had made changes to its foster care placement policy. From now on, the state would seek to place children only in "traditional family settings." As part of this new policy, child welfare officials would ask everyone applying to serve as foster parents about their sexual orientation. Those who responded that they were lesbian or gay would be placed at the bottom of a priority list that had married heterosexual couples at the top. In addition, the agency announced that existing placements with lesbian and gay foster parents would be subject to a special, bi-annual review to determine whether the children should be removed from the homes.

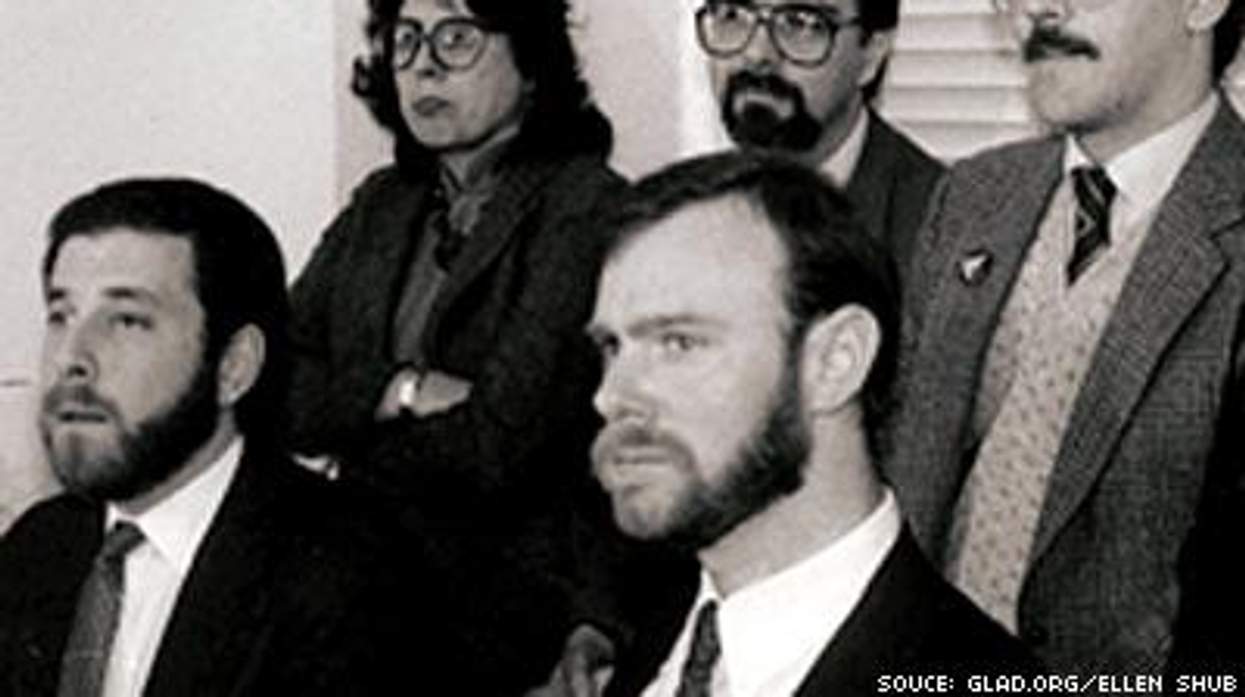

The new policy, which was drafted and instituted in a little over two weeks under the direct orders of Governor Dukakis, led to an outcry from the LGBT community, both in Massachusetts and elsewhere. Activists in Boston formed a Gay and Lesbian Defense Committee to agitate against the changed policy, while the Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders threatened a lawsuit. Several large demonstrations were held in front of the state capitol. Governor Dukakis found himself the subject of frequent protests -- some outside of his office and others outside of his home -- starting in 1985 and going all the way through 1988 when he successfully ran for the Democratic Party's nomination for president.

But the administration's new policy had powerful institutional supporters, including the Catholic Church and the Boston Globe. Archbishop Bernard Law -- who would later be removed by the Vatican from his Boston post for failing to protect children from sexually abusive priests -- urged that children be placed only with married heterosexual couples. And, in an editorial published two days after DSS announced its new policy, the Globe warned that "the state's foster-care program is not a place for social experimentation with nontraditional family settings. It should never be used, knowingly or unknowingly, as the means by which homosexuals who do not have children of their own... are enabled to acquire the trappings of traditional families." Even Ellen Goodman, the stalwart liberal Globe columnist who was otherwise critical of the decision to remove the children from Don and David's home, complained in her nationally syndicated column that "I have never understood the need of gay couples to define their relationships as 'family.'" She added, for good measure, that she was "uncomfortable with those gay women who deliberately go out to 'get' children on their own through artificial insemination."

In early 1986, Don and David filed a lawsuit against the state arguing that the new foster care policy violated their rights to equal protection and privacy. In September of that year, a trial court judge found the policy unconstitutional. The litigation dragged on for three more years, in part because the state refused to turn over documents describing internal discussions during the days following the publication of the initial Globe story. In 1988, the state supreme court ordered government officials to make the documents available to the plaintiffs. Those materials showed that Governor Dukakis and his staff, in the days following the breaking of the story, had been driven by political considerations in drafting the new foster care policy. Eighteen months after the high court issued its ruling, the state reached a settlement with Don and David, agreeing to change its foster care policy so that parenting experience -- rather than sexual orientation or marital status -- would be the most important factor in making foster care placement decisions.

In late 1990, the gay couple, elated by their victory but exhausted by their five-year battle with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, moved to a rural part of the state seeking peace and quiet. Less than two years later, that peace and quiet came to a joyful end when they adopted four siblings simultaneously, all under the age of 8.

The foster care controversy in Massachusetts led neighboring New Hampshire to enact a law in 1987 prohibiting lesbians and gay men from serving as foster care or adoptive parents. On the day the measure became law, state representative Mildred Ingram, who had been the main supporter of the bill, stated that "I'm not against homosexuals. They are adult people. They made their own choice and the only one they have to answer to is their maker. They can go on their merry way to hell if they want to. I just want them to keep their filthy paws off the children."

New Hampshire was not the first state to enact a law prohibiting gay people from adopting. That distinction went to Florida 10 years earlier. The Florida ban had its genesis in January 1977, when Dade County became the first southern municipality to enact a gay rights law. The ordinance, which prohibited employers, landlords, and places of public accommodation from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation, was hailed by the local gay community.

Many social conservatives, however, soon began pushing for its repeal, an effort that was led by Anita Bryant -- a singer, a former runner-up to Miss America in the 1950s, and a born-again Baptist. This apparently wholesome, all-American figure ended up conducting an antigay crusade driven by a vitriolic rhetoric that had never been heard before and has rarely been matched since.

Bryant and her allies centered their campaign in favor of the ordinance's repeal on the need to protect children from gay people. Indeed, opponents of the law formed a group called "Save Our Children," which published ads in newspapers contending that "the recruitment of our children is absolutely necessary for the survival and growth of homosexuality -- for since homosexuals cannot reproduce, they must recruit, must freshen their ranks." During the repeal campaign, Bryant referred to gay people as "human garbage," while criticizing the ordinance as an attempt to "legitimize homosexuals and their recruitment of our children."

Gay rights opponents collected more than 60,000 signatures -- six times the number required by law -- in order to place a repeal referendum before voters in June 1977. The conservative activists also succeeded in assembling a broad coalition in support of the repeal, one that included different religious denominations. The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Miami, for example, distributed a pastoral letter urging parishioners to vote against the gay rights law, while some local rabbis signed a statement in support of the repeal. Bryant's success in mobilizing opposition to the ordinance also caught the attention of conservative movement leaders across the country eager for national exposure -- including a minister from Virginia by the name of Jerry Falwell -- who descended into South Florida to assist in the repeal effort.

In the end, the gay rights forces were overwhelmed by their opponents. On election day, county residents voted to void the ordinance by a two-to-one margin.

The political campaign in south Florida presenting homosexuality as a threat to children led the Florida legislature, that same year, to pass the nation's first statute prohibiting gay people from adopting. At the time the law was enacted, there had been only a handful of reported instances of an openly lesbian or gay person adopting a child in the entire country, and none of those had taken place in Florida. The statute, therefore, was not so much aimed at "protecting" children from gay people as it was at sending a message of disapproval of homosexuality. As one of the measure's strongest supporters in the Florida legislature explained at the time, the law was meant to say to gay people that "we're really tired of you. We wish you would go back into the closet." The same legislator added that "the problem in Florida is that homosexuals are surfacing to such an extent that they're beginning to aggravate the ordinary folks, who have rights of their own."

While Florida (in 1977) and New Hampshire (in 1987) enacted statutes banning gay adoption, the laws in the other states remained silent on the issue. (One exception was New York, which in 1978 issued a regulation stating that adoption "applicants shall not be rejected solely on the basis of homosexuality.") This regulatory void provided lesbians and gay men, especially those living in relatively tolerant parts of the country, with the opportunity to pursue adoption as a way of becoming parents.

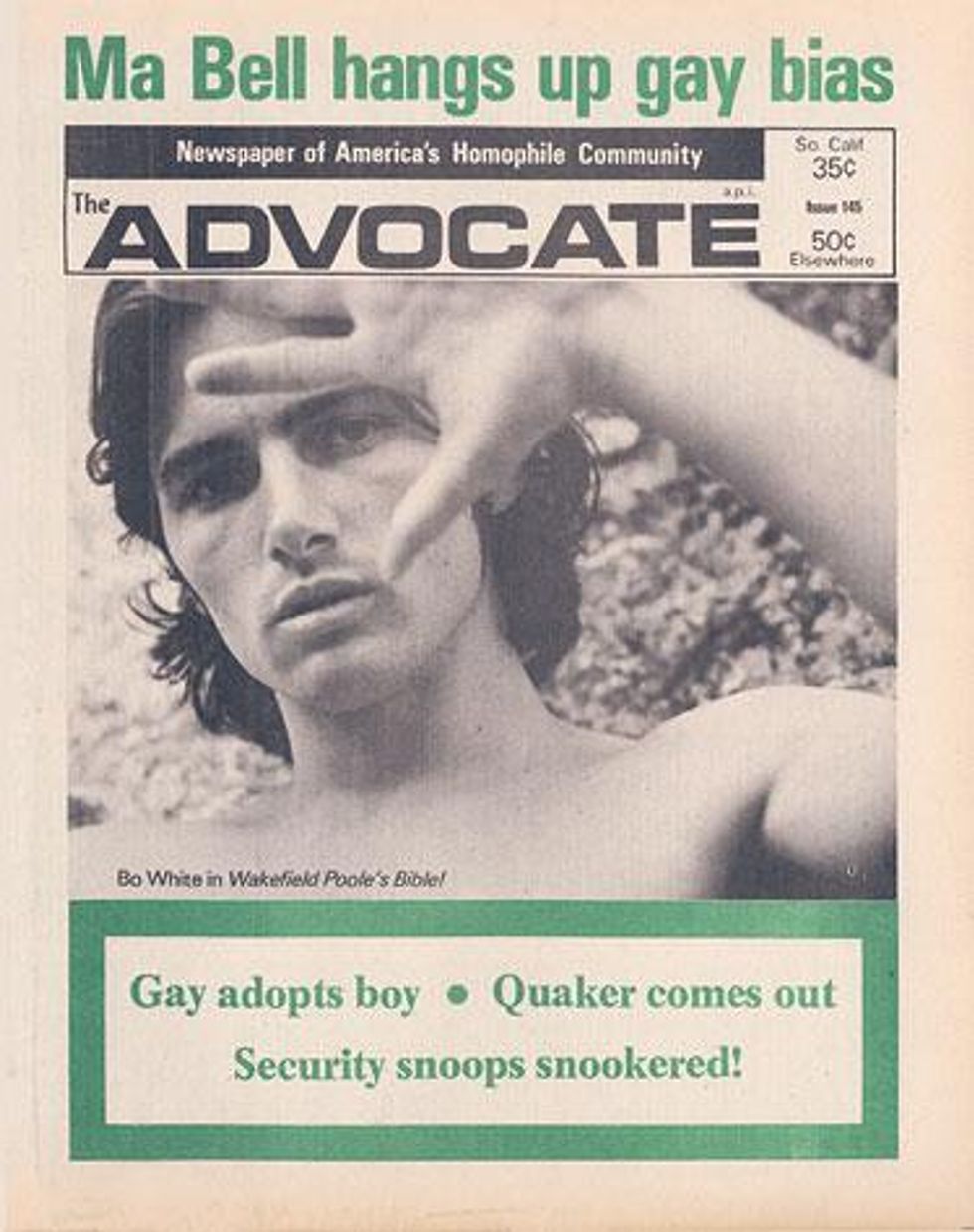

One of the earliest reports of an adoption by an openly gay person in the United States appeared on the front page of The Advocate in August 1974 (pictured). The article reported that a 12 year-old boy, whom the social worker described as having "effeminate tendencies" and whose placement had been rejected by a married heterosexual couple, was adopted by an openly gay man in southern California.

In 1979, the gay media wrote about a gay couple -- one a physician and the other a minister with the Metropolitan Community Church in San Francisco -- that had jointly adopted a 2-year-old boy. This appears to have been the first time that a same-sex couple adopted a child anywhere in the country. Also that year, the New York Times reported that a gay minister in Catskill, New York, who lived with his partner, was permitted to adopt a 13-year-old boy.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, there were other gay men, as well as lesbians, who adopted children, but many of them appear to have done so without revealing their sexual orientation. Since in most jurisdictions, prospective adoptive parents were not asked about their sexual orientation, it was possible for lesbians and gay men to refrain from volunteering information about their personal relationships without having to make false statements.

Instances in which officials denied the adoption applications of openly gay people served as clear disincentives for others to come out of the closet while seeking to become parents. In 1975, after Draffan McBride, a Scottish immigrant and a physician living in Arizona, applied to adopt a child as an openly gay man, child welfare authorities turned him down. He reapplied three years later, this time with his same-sex partner of eight years. That petition went before an Arizona trial judge who denied it because of the men's relationship. McBride later surmised that if he had not mentioned his homosexuality when he had applied as a single man, he would likely have been allowed to adopt. But he chose not to pursue that route, explaining that if "I keep things aboveboard and don't try to hide anything, then I have nothing to feel guilty about." In 1979, the state did permit a 16-year-old boy -- whose parents had thrown him out of their home after he told them he was gay -- to live with McBride and his partner until the teenager enlisted in the Army.

A few years later, another Arizona court considered an adoption application submitted by a bisexual man. The application had been endorsed by his social worker and by the appropriate state agency. The court of appeals, however, affirmed a trial judge's denial of the application, in part because of the man's bisexuality. The court, after noting that the petitioner had testified that he might have a sexual relationship with a man in the future, pointed out that sodomy was a crime in Arizona. It then went on to conclude that it "would be anomalous for the state on the one hand to declare homosexual conduct unlawful and on the other [to] create a parent after that proscribed model, in effect approving that standard, inimical to the natural family, as head of a state-created family."

But four years later, another court, this time the Ohio Supreme Court, became the first appellate court in the country to hold that the sexual orientation of an openly gay man did not legally preclude him from adopting.

Lee Balser, a psychological counselor, first met a 4-year-old boy by the name of Charlie when the Licking County (Ohio) Department of Human Services in 1986 referred the child to his office. Up to that point, the little boy had had a difficult life. The previous year, his biological parents had voluntarily transferred custody of him and his two sisters to the county because they were unable to care for the children. In addition, Charlie had been diagnosed with leukemia, though the disease was then in remission after lengthy radiation and chemotherapy treatments. Furthermore, Charlie had learning disabilities, a speech impediment, and facial features that suggested he suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome.

Starting in July 1986, Lee met with Charlie during weekly counseling sessions aimed at helping the child deal with issues of anger and low self-esteem in preparation for a future adoption. Although Charlie responded well to the sessions, Lee was concerned that, every few months, DHS moved the boy from one foster home to another. It did not take an expert to see that what Charlie needed most was a stable home life, something that the foster care system seemed incapable of providing. It was then that Lee -- who was becoming quite attached to the boy -- started considering the possibility of adopting him.

Even though DHS had placed Charlie in its adoption registry shortly after his biological parents gave up custody of him the year before, no one had stepped forward expressing interest in adopting him. When Lee first started thinking about the possibility of doing so, he discussed the matter with his partner Tom Kuzma, a research scientist with a Ph.D. in Astronomy, with whom he shared a home in Columbus. At first, Tom was unsure about whether he wanted to help raise a child. But after many conversations with Lee and after Tom started spending time with Charlie -- in February 1987, DHS agreed that Charlie could visit regularly with the gay couple -- he came to support the idea of Lee adopting the boy.

A few weeks later, Lee informally let officials at DHS know that he would be interested in adopting Charlie and suggested that the agency conduct a study of his home. Rather than doing so, DHS became more proactive in trying to find a permanent (heterosexual) home for the boy. In May 1987, it located a married, heterosexual couple who expressed interest in adopting Charlie. But after the agency began taking steps to place Charlie with them, the couple changed their mind and decided not to go through with the adoption.

In the meantime, DHS moved Charlie yet again to a new foster home after he had difficulties in the home of a foster mother -- who had fostered more than 200 children for the county through the years -- because her rigid parenting style did not mesh well with Charlie's behavioral problems. Knowing that he could provide the loving and stable home that the boy so desperately needed, and tired of waiting around for the agency, Lee in January 1988 filed a court petition seeking to adopt Charlie.

Since DHS had legal custody of the boy, it had to consent to the adoption. Every week following the filing of his petition, Lee called the agency to inquire whether it would provide its consent. And every week he was told that the matter was under advisement. Three months later, and only one day before the scheduled court hearing on Lee's adoption petition, the agency's executive director announced that it would oppose the adoption.

At the hearing, two psychologists testified on Lee's behalf. The first told the court that sexual orientation was irrelevant to the question of whether someone could be a good parent. The second testified that Lee and Charlie had developed a tight bond and that given Charlie's medical and emotional issues, he needed the stability, care, and love that Lee was willing and able to provide. After stating that Lee would be a good parent and that he could handle Charlie's behavioral problems, the expert witness added that "my concern isn't so much that Mr. Balser gets Charlie, but that Charlie gets Mr. Balser." In addition, the guardian at litem assigned to represent Charlie recommended that Lee's adoption petition be granted.

The government's only witness was a DHS administrator who told the court that the agency had developed a profile of the type of family that it believed would be best suited to adopt Charlie, one that consisted of two parents who had prior parenting experience, a proven ability to deal with behavioral issues, and "a child-centered lifestyle." The agency's position was that Lee did not meet most of its criteria. For example, the DHS administrator told the court that Lee did not lead "a child-centered lifestyle" because he had been a single man -- his five-year relationship with Tom apparently did not count -- all of his adult life. She also expressed concern that "society's view of a homosexual family may make it difficult for homosexual parents to access and receive" the type of medical and educational services that a special needs child like Charlie required. Finally, the witness testified that the agency had contacted other child welfare agencies in Ohio and elsewhere, only to learn that none of them had ever approved an adoption by an openly gay person.

It was not clear how the judge was going to rule on the adoption petition, especially after he asked Lee at one point whether "if you adopt Charlie, are you going to turn him into a homosexual?" (Lee answered that the boy's sexual orientation would be something for him to figure out on his own when he grew older.) But several weeks after the hearing, the judge issued an order approving Lee's adoption petition. The government immediately appealed and successfully got a stay of the trial court's ruling.

The law in Ohio, like that of most states, was silent on the question of whether gay people could adopt. The Ohio adoption statute permitted both married couples and unmarried persons to adopt. Since Lee was not married, and since the statute did not address the question of sexual orientation, it seemed clear that he was not, as a matter of law, prohibited from adopting. But the Ohio Court of Appeals, in a poorly reasoned opinion, overturned the lower court's ruling after concluding that Ohio law, in fact, categorically prevented gay people from adopting children.

The court provided two rationales in support of its reading into the statute a gay adoption ban that had not been enacted by the legislature. First, the judges opined that "homosexuality and adoption are inherently mutually exclusive" because "homosexuality negates procreation." The relevancy of this observation, however, was not clear since adoption and procreation are two different ways of becoming a parent. In fact, many heterosexual couples who choose to adopt do so precisely because they cannot procreate. The ability to procreate, therefore, does not distinguish those couples from gay people interested in adopting.

Second, the court noted that a child raised by "announced homosexuals" will not be able "to pass as the natural child of the adoptive 'family' or to adapt to the community by quietly blending in free from controversy and stigma." According to the court, "adoption imitates nature," which meant that "a fundamental rationale for adoption is to provide a child with the closest approximation to a birth family that is available."

The court's understanding of adoption, while once widely shared, had by the late 1980s become dated and anachronistic. By then, few in the child welfare and adoption fields still believed that it was crucial for adopted children to "blend in" with their adopted families so that outsiders would not know that they had been adopted. The Ohio Supreme Court had itself made this point clear when it ruled in 1974 that a white couple could adopt an African-American child, a decision that was consistent with one from twelve years earlier in which the court permitted a white man and his Asian wife to adopt a Latino child.

As suspect as the court's reasoning was, its ruling meant that Lee would not be able to adopt Charlie unless the Ohio Supreme Court reversed. In arguing its case before that court, the government contended that it would not be in Charlie's best interests "to be adopted into the home of two male homosexuals living as husband and wife in a relationship they consider a marriage." The government lawyers insisted that gay people were not the kinds of "parental role models" that children needed.

But for the Ohio Supreme Court, the legal issue was a straightforward one: It was up to the legislature to decide whether gay people were eligible to adopt. The legislature had not explicitly prohibited gay people from adopting; instead, it had expressly concluded that any unmarried adult could file an adoption petition, one that should be approved if doing so was in the child's best interests. As a result, the state high court ruled that the Court of Appeals had erred when it categorically excluded an entire group of individuals from adopting in the absence of a legislative mandate.

The law required adoption petitions to be considered on a case-by-case basis depending on the particular circumstances of the child and of the prospective parent. Since Lee was not, as a gay man, legally precluded from adopting and since the trial court had found that the adoption was in Charlie's best interests, the state supreme court ordered that the adoption decree be issued.

It bears noting that not every justice on the Ohio Supreme Court joined the majority opinion. The sole dissenting judge would have sided with the government, but would have relied on a different -- though not any less problematic -- rationale than the one embraced by the Court of Appeals. This judge would have denied the adoption petition because Lee Balser was a gay man who, despite being HIV-negative, was at risk (the judge believed) of being infected with the virus in the future, which in turn supposedly placed Charlie at risk of getting AIDS. The dissenting judge noted that the boy's immune system was already compromised as a result of the leukemia treatment. Acquiring HIV, the judge feared, would further compromise the boy's immune system.

Although the dissenting opinion did not carry the day, it is nonetheless indicative of the extent to which some judges were willing to go to deny LGBT people the opportunity to become parents. By the time the Ohio Supreme Court issued its opinion in 1990, it was widely understood that HIV was not transmitted through casual household contact. Yet, this did not prevent the dissenting judge from concluding that a gay man -- even one who was HIV-negative -- should be prevented from adopting a child.

After the Ohio Court of Appeals reversed his ruling allowing Lee to adopt Charlie, the trial judge granted temporary custody of the boy to Lee's sister Edna Balser until the state supreme court could review the case, a wait that lasted fifteen months. The Court of Appeals' ruling had been so adamant in its opposition to the idea that gay people should be permitted to adopt, that Lee, Tom, Edna, and Lee's mother spent many hours discussing how it might be possible to keep Charlie in the family if that ruling was upheld. The only way of achieving that goal seemed to be for Edna to adopt Charlie. So a month after the Court of Appeals' decision, Edna filed a petition to adopt the seven-year-old boy.

In the end, that adoption was not necessary because the state supreme court ruled that Lee's sexual orientation was not a legal impediment to his adopting the boy. The court's decision cleared the way for Lee (and Tom) to take the boy into their home to care for him permanently while experiencing the unique joys and satisfactions of parenthood. As an emotional Lee put it at the time, "[t]here's something special about a kid putting his arms around you and kissing you and saying, 'good night, daddy.'"

Although everyone involved in assessing Lee Balser's adoption petition, from the trial judge to the county welfare officials, knew his partner would play an important (even parental) role in Charlie's life, Tom did not join Lee's petition. That Tom did not also seek to legally adopt the boy was hardly surprising; it was difficult enough, in the 1980s, to get courts to approve an adoption petition brought by an openly gay man; to add his same-sex partner to the petition diminished the likelihood of approval even more because the issuance of the adoption decree might be perceived as a form of judicial condoning of the same-sex relationship.

Joint adoptions by lesbian and gay couples were rare before the mid-1990s. ("Joint adoptions" are those in which two individuals, neither of whom is already a legal parent of a child, become his or her parents simultaneously. Such adoptions should be distinguished from "second-parent adoptions." In those adoptions, there is already a legal parent and the question is whether the parent's same-sex partner can become a second parent through adoption.) But as some child welfare officials, social workers, and judges grew more comfortable with adoptions by individual lesbians and gay men, the push soon came for the recognition of joint adoptions. One of the earliest and most important joint adoption cases took place in New Jersey.

When Michael Galluccio and Jon Holden, a gay couple in their early 30s, first decided to try to become parents in 1994, they were advised by a child placement specialist with the New Jersey Division of Youth and Family Services to settle for being foster parents because state officials would never allow a same-sex couple to adopt together. Since this was not a problem for the couple -- the two men were unsure whether they wanted to commit to permanent parenthood anyway -- they went ahead and enrolled in the state's foster care licensing program. During that process, in response to inquiries by officials, the couple made it clear that they would gladly accept a child with special needs.

Six months later, after they were certified as foster parents, DYFS placed a 12-week baby boy by the name of Adam in their home. The identity of the child's father was not known. The mother was a heroin and cocaine user who was HIV-positive. Adam was born prematurely and spent the first few days of his life in the intensive care unit after testing positive for HIV antibodies. He also had respiratory problems, cardiac arrhythmia, and a hole in his heart's left ventricle (a condition that doctors believed would heal on its own). For the first six weeks of his life, Adam was given the AIDS drug AZT with the hope that the virus would not take hold in his little body. He was also on several other medications, including one that helped him cope with the tremors and seizures caused by the withdrawal from heroin and cocaine that he experienced once he was no longer connected to his mother's bloodstream.

Although Michael and Jon had thought, before Adam arrived in their home, that being foster parents might be enough for them, once they started caring for and bonding with the baby, they quickly decided that they wanted to keep him permanently. Concerned about what the placement specialist had told them the year before about their ineligibility for adoption, they made inquiries of Adam's social workers and other state employees involved in overseeing his care. This time, they were assured by everyone at DYFS with whom they spoke that both men would be able to adopt Adam together.

But after they officially requested that DYFS consent to the adoption so that they could file an adoption petition in court, the agency informed them that the prior statements by its employees had been mistaken because agency policy prohibited unmarried couples from adopting jointly. State officials were willing to consent to Michael's adoption of Adam, but not to Jon's.

DYFS's sudden reversal left the gay couple with an excruciatingly difficult decision to make. They could proceed with a single-parent adoption, which would provide many benefits to Adam, including making it much more difficult for state officials to remove him from his home. It would also permit Adam, who needed constant medical treatment and attention, to be added to Michael's generous employer-provided health insurance. (As a child in the foster care system, Adam was covered by Medicaid, but as Michael and Jon learned soon after the boy was placed in their home, many of the doctors with the best reputations did not accept Medicaid patients because of that program's low payment rates.)

While there were good reasons for proceeding with Michael's adoption of Adam, it was also the case that the two men had jointly cared for the boy for almost a year while together nursing him into good health. They both considered themselves to be Adam's parents, and it seemed like a betrayal of the boy for Jon not to join in the adoption petition. In addition, they were worried what would happen to Adam if Michael, after adopting him on his own, died suddenly. There would be no guarantee that the state would then permit Jon to continue raising the child.

The couple did have the option of adopting Adam consecutively. Michael, in other words, could have filed an adoption petition on his own first, and after it was granted, then Jon could have filed his. This was possible because New Jersey courts had recently started approving second-parent adoptions. But there were significant drawbacks to this option: Not only would doing a second adoption be more expensive, but the problems associated with the failure to recognize Jon as a legal parent would remain in place for the several months -- if not longer -- that it would take to complete the second-parent adoption. After giving the matter much consideration, the couple decided to pursue the joint adoption by trying to persuade the agency, through letters and phone calls, to change its mind and allow both men to adopt together.

At around this time, Michael and Jon received the terrible news that Adam's biological mother had died of a drug overdose. Only a few weeks later, DYFS proposed that the couple take in another baby boy by the name of Andrew. Andrew's mother -- who, like Adam's late mother, was HIV-positive and a drug user -- had given birth to the premature baby and then checked herself out of the hospital leaving the child behind. The baby was now two and a half months old, still in the hospital, and had not been visited by any family members.

By now, Adam was almost a year old and his health was finally stable. Michael and Jon worried that they might not be able to cope physically and emotionally with taking in a second child, especially one who was just as sick as Adam had once been, while at the same time trying to pressure DYFS to allow them to adopt Adam together. It was clear, however, that baby Andrew desperately needed a home. As a result, despite their qualms, the couple accepted the placement.

In the end, Andrew remained in their home for only two months because the child's grandmother stepped forward and requested custody of the boy. The agency's mismanagement of the case -- it had not known there was a grandmother who might be willing to take the boy -- created further emotional turmoil for the gay couple. But as foster parents, they could not refuse the state's demand that they turn the child over. The whole incident only reinforced in their minds the need for both of them to adopt Adam as soon as possible.

The gay couple continued making inquiries of the agency regarding whether it would make an exception to its policy and permit them to adopt together. Every time they were turned down, the couple moved up the bureaucratic ladder another notch, until finally they heard back from the Commissioner of the Department of Human Services, who like every other state official before him, gave them the same answer: No.

It was now clear that if Michael and Jon were going to be able to adopt Adam, they would have to take the state to court. The couple contacted the ACLU seeking its assistance, and the organization agreed to represent them. The ACLU lawyers promptly wrote DYFS warning officials that they would have a lawsuit in their hands if they insisted in prohibiting the two gay men from adopting jointly.

Incredibly, at the same time that DYFS was refusing the men's requests to allow them to adopt Adam together, it continued its efforts to try to place additional foster children -- all of them HIV-positive -- in their home. The agency's requests exposed the contradictions of its own policies; on the one hand, it would not allow the men to adopt jointly; on the other, its officials knew perfectly well that the couple were providing excellent care to Adam, and that they could do the same for other children in need. The problem was not that the agency had doubts about Michael and Jon's ability to be good parents -- instead, the problem was that child welfare officials did not want to be perceived as condoning adoptions by gay couples.

In the months that followed, Michael and Jon refused three additional placements of baby boys after concluding that they needed to settle the matter of Adam's adoption before accepting new children. But their resolve gave way when the state came back with another proposed placement, this time of a baby girl. The child's name was Madison; she was born prematurely and had tested positive at birth for the HIV antibodies and for heroin. The prospect of raising a baby girl, along with the little boy who was already in their home, simply proved too irresistible for the two men to turn down.

A few months after welcoming Madison into their home, the couple was elated to learn that Adam, as HIV-positive children sometimes do, had seroreverted to being HIV-negative. While the boy had had HIV antibodies in his bloodstream for many months after his birth, they were there in response to his mother's HIV. Adam, it turned out, did not have the actual virus.

In the spring of 1997, the New Jersey attorney general sent the couple's lawyers a letter stating that the government was now willing to make a one-time only exception to its policy regarding adoption by unmarried couples by not objecting to Michael and Jon's petition to jointly adopt Adam. The letter went on to explain that, although the state would not stand in the way of this particular adoption, it would not affirmatively support the petition either, thus leaving it to a judge to approve or disapprove of the adoption without a state recommendation.

The state's decision on how to handle Adam's adoption left Michael and Jon with another difficult decision to make. They could accept the attorney general's offer and proceed with what they had wanted all along, which was to file an adoption petition jointly, in the hope that a judge would approve it. Or, they could continue with their plan of suing the state. If they won the suit, not only would they be able to proceed with their adoption of Adam (and later of Madison), but it would also mean that unmarried couples, both gay and straight, across the state would be able to adopt jointly.

After mulling it over, the two men decided that there was more at stake than just their adoption of Adam. The state's policy of prohibiting unmarried couples from adopting jointly was hurting children because it unnecessarily denied countless foster children the opportunity to be adopted by two parents who could provide stable and nurturing homes for them. As a result, Michael and Jon decided to sue.

In their dealings with the state up to this point, the couple had engaged in quiet, behind the scenes efforts to try to persuade DYFS to change its policy. But the time for discrete lobbying was over. It was now necessary to publicize their fight with the state, which the couple did by holding press conferences, granting media interviews, and telling anyone who would listen that New Jersey's restrictive adoption policy was harming children.

In the meantime, the ACLU filed a class action lawsuit, with Michael and Jon serving as lead plaintiffs, challenging the constitutionality of the state's adoption policy. The gay couple also filed a petition in court seeking to adopt jointly. The former, more complicated, legal case claimed that the policy violated the constitutional rights of unmarried couples, both gay and straight, to the equal protection of the law. The issue in the latter case was the more straightforward one of whether the adoption of Adam by both Michael and Jon was in his best interests. Both cases were assigned to Superior Court Judge Sybil Moses.

Everyone involved in the case knew that if Moses ruled favorably on the adoption petition, she might be open to the possibility of later striking down the state's policy as unconstitutional. In contrast, if she ruled against Michael and Jon on their adoption petition by concluding that it would not advance the child's welfare, it was unlikely that she would rule against the state in the class action suit.

In October 1997, Judge Moses ruled that Michael and Jon could jointly adopt Adam. Although that ruling focused on the specific circumstances of the proposed adoption and did not address the constitutionality of the state's policy, the judge was now on record in holding that a joint adoption by a gay couple was in the best interests of a child. This made it entirely possible that she would proceed to strike down the policy after concluding that there was no valid justification for excluding all unmarried couples from the pool of individuals eligible to adopt.

Fearing that possibility, the state decided two months later to settle the class action lawsuit by agreeing to revise its adoption policies so as to allow unmarried couples to adopt jointly. In doing so, New Jersey became one of the first states in the country to institute an explicit policy providing same-sex couples equal standing with heterosexual married couples when it came to adopting children.

On the day that Judge Moses issued her ruling approving their joint adoption of Adam, Jon had told the gathered media outside the courtroom -- with Michael by his side holding their son in his arms -- that "we are so grateful for what has happened today. We're a family now." But the struggle by both men to adopt their son had always been about more than just their family. As Michael said at a press conference held two months later to announce their settlement agreement with the state, "this is a victory about goodness and equality. It is a victory for all families."

In the early 1980s, as the number of lesbians having children through alternative insemination started growing, lawyers working with lesbian mothers -- including Donna Hitchens in San Francisco, Allison Mendel in Anchorage, and Nancy Polikoff in Washington, D.C. -- began discussing among themselves how to help the female partners of biological mothers attain equal parental status. As the lawyers brainstormed about how to accomplish this, they kept coming back to the law of adoption.

When the lawyers re-read adoption statutes with lesbian couples in mind, they identified some potential difficulties. The adoption laws of all the states required that the rights of the legal parents be terminated before a child could be adopted. This presented a problem for the lawyers because their clients did not want the biological mother's parental rights terminated; instead, the goal was to add her partner as a second parent.

There was one exception to the termination requirement, one that allowed the parents' spouses to adopt their children without first terminating their parental rights. Although it was possible to argue that courts should treat same-sex couples who were raising children together as if they were spouses for purposes of adoption law, it was highly unlikely that courts in the 1980s would do so. Indeed, lawyers working with lesbian and gay parents from the 1970s on generally sought to separate parent-child issues from relationship-recognition ones. This allowed the attorneys to emphasize to judges that the cases were about protecting the relationship between adults and children rather than about the legal validation or recognition of relationships between adults.

Faced with the challenges presented by the wording of the adoption statutes, Hitchens, Mendel, Polikoff and a handful of other lawyers creatively came up with a potential solution: What if the biological mother, in effect, sought to adopt her own child at the same time that her partner filed an adoption petition? Although this would mean that the biological mother's rights would be terminated, she would then be immediately recognized, along with her partner, as an adoptive parent of the child.

But there were also difficulties with this way of proceeding, starting with the fact that there were no precedents for the proposition that parents could adopt their own children. Furthermore, although all jurisdictions allowed married couples to adopt, and many permitted single people to do the same, it was unclear under the laws of most states whether unmarried couples could adopt together. In the end, all of these complicated legal issues would have to be worked out, case-by-case and jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction, in the courts.

One of the first times in which a judge recognized a second-parent adoption, and wrote an opinion backing it up, was in the case of Laura Solomon and Victoria Lane. The two women, both of whom were professional educators who worked with disabled and emotionally troubled children in Washington, D.C., met in 1979 when Laura was twenty-seven and Victoria twenty-nine. The following year, they moved in together, and in 1983, before a large gathering of family and friends, they participated in a commitment ceremony.

The two women, early on in their relationship, decided they wanted children. They at first tried to adopt a child, but when that effort proved unsuccessful, they decided that Laura would be inseminated with sperm from an anonymous donor. In 1985, Laura gave birth to a baby girl whom the couple named Tessa. The two women gave the child their combined surnames to reflect the fact that they both considered themselves to be her parents and they wanted others to do the same. After Tessa was born, the couple began raising her together, dividing childcare responsibilities between themselves and jointly making all decisions about her welfare.

When Tessa was four years old, the couple decided to bring a second child into their home. In 1989, Victoria traveled to Nicaragua and adopted a baby girl whom the coupled named Maya. As with Tessa, the two women gave Maya each of their surnames and began raising her together.

One concern that all couples in this situation worry about is what would happen if one of them were to die suddenly. Only a surviving legal parent is presumptively entitled to custody. This means that if a child has one legal parent and that parent dies, it makes the child a legal orphan. The only way of assuring that the child will be able to continue living with the surviving member of the couple is if he or she adopts the child.

It so happened that all of Laura and Victoria's family members were supportive of their relationship and of their decision to raise children together. As a result, Tessa and Maya were fully integrated into the women's extended families with no one differentiating between them according to biology, adoption, or which mother was the legal parent. It was therefore unlikely that a family member would petition the court for custody if one of the women were to die. Furthermore, the couple had entered into a parenting agreement, which in addition to expressing their intent to raise the children together, also named each other as their legal child's guardian in case of death. Nonetheless, there was a peace of mind that would only come with knowing that they were both the legal parents of both of their daughters.

There were other benefits that would follow if the law were to recognize the relationship that the lesbian couple had with both girls. Each child would be able to inherit property from both mothers (as well as from the families of both women). Each child would also be eligible to receive Social Security survival benefits and health insurance coverage from both women. In addition, third parties (such as schools and hospitals) would have to honor decisions made on their behalf by both women. Finally, if the mothers' relationship were to end, the children would benefit from rights of access to and support from both parents.

It was also the case that, as matters stood then, Tessa and Maya were legal strangers to each other. This was so despite the fact that they were being raised in the same home as sisters by the same two parents. Only the recognition of parental rights over both children by both women could avoid the confusion and uncertainty that the two girls would experience when they grew older and learned that the law did not recognize their relationship as sisters.

In 1982, before Laura and Victoria had children, they joined a group in Washington, D.C., consisting of lesbians who were considering having children. There they met and befriended Nancy Polikoff, a lesbian lawyer who had been a founding member of the Washington DC Feminist Law Collective and was among the earliest legal advocates for lesbian mothers. Several years later, after the couple started raising their two daughters, they asked Polikoff to draft and file second-parent adoption petitions on their behalf. Polikoff -- who was by then a law professor at American University -- believed that Laura and Victoria's case would be a good second-parent adoption test case because the two women were so clearly committed to each other and to their children.

In the summer of 1990, Polikoff filed two petitions with the District of Columbia's Superior Court on behalf of her clients, one to jointly adopt Tessa and another to jointly adopt Maya. The District's Department of Human Services (the Department), after speaking to references and conducting a study of the couple's home, found that the two women "are caring persons who express interest in the overall well-being of the adoptees and who are providing them with good care."

Despite this finding, the Department recommended to the court that the adoption petitions be denied based on its lawyers' view that the granting of an adoption petition filed by a party who was not married to the legal parent required the termination of the latter's parental rights. In other words, under the lawyers' interpretation of the District of Columbia's adoption statute, the only way for each woman to adopt the other's child was if her partner's parental rights were first terminated. The lawyers also believed that the adoption petitions could not be granted because the adoption statute did not contain an explicit provision authorizing an adoption by two individuals of the same sex.

After the Department came out in opposition to the proposed adoptions, Polikoff wrote directly to Mayor Sharon Pratt Dixon urging her to review the issue personally. In the letter, Polikoff explained that her two clients had been together for more than ten years and were raising the children jointly. Polikoff added that if the Department's position on her client's adoption petitions did not change, it would reflect poorly on the mayor who had recently been elected after campaigning as a strong supporter of gay rights. Although Polikoff was not asking that Dixon endorse all adoptions by lesbians and gay men, she did request that her administration support a reading of the adoption statute that would permit judges to grant adoption petitions filed by unmarried couples if doing so was in the best interests of the children.

The letter worked. Several weeks later, after the Mayor's office asked the Department to reconsider its position, it filed a supplemental report with the court in which it recommended that the adoption petitions be granted.

The facts in second-parent adoption cases are rarely in dispute, and Laura and Victoria's case was no exception. The record in the case was replete with evidence regarding the lesbian couple's committed and stable relationship and their ability to provide the girls with much love and good care. There is also in second-parent adoption cases usually little dispute that the children in question would benefit from having two legal parents. As trial judge Geoffrey Alprin eventually concluded, the couple's claims that Tessa and Maya would benefit legally and emotionally from the court's approval of the adoption petitions had "overwhelming record support."

Instead, the issues in most second-parent adoption cases are almost always purely legal ones of statutory interpretation. Although the Department had originally contended that the adoption statute did not permit two individuals of the same sex to adopt the same child, Polikoff noted in her legal papers that the only explicit restriction in the law itself on the ability of anyone to be eligible to adopt was a provision that prohibited married individuals from adopting a child unless their spouses joined in the petition. There was no explicit provision prohibiting two unmarried individuals, regardless of their sex, from adopting together. And in the absence of such a provision, there was no statutory impediment to Laura and Vanessa's filing adoption petitions that would make both of them the legal parents of both girls.

Potentially more problematic for Polikoff's clients was the termination of parental rights provision contained in the District's adoption statute. That provision stated that after an adoption decree is granted, "all rights and duties... between the adoptee [and] his natural parents... are cut off." In dealing with this provision, Polikoff argued that its application was discretionary rather than mandatory because the legislature could not have intended for the rights and obligations of the "natural" parent to be terminated in every adoption case regardless of whether doing so was in the best interests of the children. The provision in question, Polikoff explained in her legal papers, protected the welfare of children in cases in which the "adoptive parents and the adoptee will be forever strangers with the biological parents." But this was clearly not the case in a proposed adoption of children by two individuals who intended for the same family unit that existed before the adoption to remain in place after the adoption.

Judge Alprin eventually agreed with Polikoff's analysis, noting in an opinion issued in August 1991 that "it would be unfortunate if the court were compelled to conclude that adoptions so clearly in the best interests of the prospective adoptees could not be granted because of a literal reading of a statutory provision obviously not intended to apply to the situation presented in these cases." The judge also pointed out that the "cut off" provision, according to the statute itself, did not apply to adoption petitions filed by stepparents. Alprin concluded that it would be as inappropriate to require the termination of the "natural" parent's right in a case involving a lesbian couple in a committed relationship as it would be in a case in which a stepparent sought to adopt the child of his or her spouse.

With their legal victory in hand, Laura and Victoria now had the peace of mind in knowing that they were each the legal parents of both their daughters. Unfortunately, that sense of security was tested in the most tragic of ways two years later. One day, while Victoria was driving her car with her two daughters in the back seat, a sudden and violent rain storm hit. The storm's fierce winds caused a large tree limb to fall, smashing through the windshield and striking Victoria with great force. Although the children were not harmed, Victoria was severely injured. She survived many hours of surgery, but died two weeks later of an infection.

Victoria's tragic death would have left four-year-old Maya an orphan, an unsettling possibility that was avoided only because she had been adopted by Laura. That adoption also meant that Tessa (and not just Maya) received Social Security death benefits after Victoria's death. This provided Laura with additional funds to take care of the girls' needs after the loss of Victoria's income. As difficult as it was for Laura and her two daughters to cope with Victoria's death, the second-parent adoption worked as intended by providing stability, continuity, and economic benefits to the survivors. As Judge Alprin put it after Victoria's death, "it is tragic that we had to have such obvious and direct evidence of the need" for the second-parent adoption.

The opportunity for appellate review arose in 1994 when District of Columbia trial court Judge Susan Winfield ruled that the members of a gay couple could not both be recognized as the legal parents of a child whom they were jointly raising.

Bruce Moffit and Mark Dalton, both life-long Catholics in their late twenties, met in 1990 at a church service sponsored by Dignity, an LGBT Catholic organization. After dating for a few months, they moved in together and began thinking about becoming parents. In 1991, the couple placed an advertisement in a newspaper looking to adopt, an ad that was read by Sylvia Leffs, a young African-American woman who was several months pregnant. Sylvia arranged to meet with the two white gay men and liked them immediately. After several meetings, she told them that she would give them her child to raise after she gave birth. She also moved in with Bruce and Mark for the last few months of her pregnancy because she was not getting along with her mother at home.

Sylvia gave birth to a baby girl she named Hillary in August 1991. Three months later, she signed a form consenting to the adoption of her child. (Hillary's biological father could not be found and his consent was waived.) A day after that, Bruce filed a petition in court to adopt the girl. After a favorable recommendation by the Department of Human Services, Judge Winfield in 1993 granted the adoption knowing that Hillary would be raised by both Bruce and his partner Mark in their home.

Since the gay couple had always intended to raise a child together, they jointly filed a petition to adopt Hillary two months after Judge Winfield granted Bruce's petition. But this time around, the judge denied the petition.

Judge Winfield recognized that the second-parent adoption would be in the girl's best interests. She also acknowledged that Hillary would continue to live with, and be cared by, the two men regardless of whether she granted the adoption petition. But in her view, the adoption statute did not permit two unmarried individuals to adopt the same child.

While Judge Alprin had held that the statute's failure to explicitly address whether an unmarried couple could adopt together meant that such an adoption was not prohibited by law, Judge Winfield reached the opposite conclusion by holding that the absence of an explicit statutory authorization meant that the adoption petition could not be granted. Winfield reasoned that since adoption had not existed at common law and was entirely a legislative creation, the adoption law had to be read narrowly. Otherwise, she believed that the court, in effect, would be improperly legislating by expanding the scope of the statute. She added that "the Legislature could not have foreseen the occurrence of the societal changes which have drastically altered our notions of what constitutes a 'normal' family. To hold that the Adoption Code provides a remedy for petitioners' problem is to impute an intent to the Legislature that it is highly unlikely to have held."

When Bruce and Mark decided to appeal Winfield's ruling to the Court of Appeals in 1994, they turned to Polikoff to handle their case. In her brief to the appellate court, Polikoff made the same arguments that she had successfully raised more than three years earlier in Laura Solomon and Victoria Lane's case. In doing so, she urged the court to reject Judge Winfield's narrow and formalistic interpretation of the statute, one that required that the legislature have specifically contemplated the issue of second-parent adoptions before Bruce and Mark could both become Hillary's legal parents. Polikoff asked the court to instead focus on the statute's overarching purpose, which was to advance the best interests of the children.

The appellate court did precisely that a few months later when it issued a 30-page opinion rejecting Winfield's restrictive interpretation of the statute. Noting that it had in the past called for a liberal construction of the adoption law in order to effectuate its purposes, the court held that the appropriate approach was to interpret the statute in ways that would advance Hillary's best interests. Those interests, the court concluded, would not be promoted through the judicial imposition -- in the absence of an explicit statutory provision -- of a rule barring all unmarried couples like Bruce and Mark from adopting a child like Hillary. Instead, Hillary's welfare would be better promoted if the law recognized what was already in fact that case: that the young girl had two fathers who cared for her and who loved her very much.

Bruce and Mark's victory before the Court of Appeals caught the attention of conservative members of Congress, the body that has ultimate legislative authority over the District of Columbia. Beginning in 1995, some members of the House of Representatives tried to attach an amendment to the District's appropriation bill that would prohibit unmarried couples from adopting together. For several years in a row, Polikoff worked with the Human Rights Campaign and other LGBT rights groups to defeat the amendment. Those efforts helped to keep it from being voted out of committee and onto the floor of the House.

But in 1999, amendment supporters brought the measure directly to the floor and it passed the House. The Clinton Administration, however, made it clear behind the scenes that it was opposed to the provision, and it was dropped from the final District appropriation bill when the House's version was reconciled with that of the Senate's. This meant that same-sex couples raising children together in the nation's capital were able to continue to have the option of strengthening and protecting their families through second-parent adoptions.

By the time the Court of Appeals issued its ruling in Bruce Moffit and Mark Dalton's case in 1995, the highest courts of Massachusetts and Vermont had already authorized second-parent adoptions. But some courts had refused to do so. The year before, the Wisconsin Supreme Court had held that a same-sex couple could not adopt the same child. That court reasoned that since the legislature had explicitly created only one exception, that of stepparents, to the requirement that the rights of all legal parents be terminated before an adoption petition could be approved, it must have intended for that exception to be exclusive of all others. As a result, the lesbian partner of a legal parent was not allowed to adopt the latter's child even though everyone involved with the case, including the trial judge and the supreme court justices, recognized that the adoption would have been in her best interests.

But most appellate courts that have since grappled with the issue of second-parent adoptions have approved them. And in two states (Colorado and Connecticut) in which appellate courts refused to recognize second-parent adoptions, the legislatures later enacted statutes explicitly doing so. This means that, as of 2011, appellate court rulings prohibiting second-parent adoptions stand in only three states (Ohio, Nebraska, and Wisconsin).

While some legislatures have enacted statutes explicitly allowing second-parent adoptions, others have passed laws prohibiting them. Mississippi, for example, has a law that prohibits same-sex couples from adopting. And Utah has a statute in the books that prohibits cohabiting couples from adopting jointly. But the most infamous gay adoption ban is the one whose history we explored earlier in this chapter, that of Florida's.

When a state social worker asked Steven Lofton and Roger Croteau in 1988 to serve as foster parents for an eight-month old baby boy by the name of Frank, they were at first unsure what to do. The reason for the gay couple's uncertainty was not that the child had tested positive for the HIV antibodies; both men were pediatric nurses at a Miami hospital -- Roger worked in the hospital's pediatric AIDS unit -- so it was not the boy's medical condition that gave them pause. It was just that the two gay men in their early thirties had never envisioned themselves as parents. What in the end convinced them to take Frank into their home was his mother's personal request that they do so as she lay dying in a hospital bed of AIDS-related complications.

In the months after Steven completed the necessary foster care training and received his license, the state placed not only Frank in Steven and Roger's home, but also two other HIV-positive children -- Ginger, a six-month-old who was in relatively good health, and Tracy, a 1-year-old who barely weighed 12 pounds, could not hold a formula bottle in her hands, had been hospitalized a dozen times, and suffered from such a severe sinus condition that the men -- for more than two years -- had to suction her several times a night to keep her breathing while she slept.

Because of the challenges that came with caring for HIV-positive children, the state insisted that Steven quit his job so that he could be with the children all day. Roger continued working as a pediatric nurse while also helping with the childcare at home. As the two gay men settled into raising the three children that the state placed in their care, they committed themselves to providing them with as much love as they could muster while aggressively pursuing every medical option available to keep them as healthy as possible at a time when most children with AIDS did not live past the age of 2 or 3.

All three children placed by the state in Steven and Roger's home were African American, while the two gay men were white. Children from racial minority groups are overrepresented in the country's child welfare system, and Florida's is no exception. It is therefore not unusual for state agencies to place minority children with white foster parents, including lesbians and gay men.

There are not many individuals who would volunteer to raise three young children with serious medical issues, but Steven and Roger carried out their parental responsibilities with a sensitivity and an aplomb that left even the most jaded social workers amazed. Eventually, the state child welfare agency that placed the children in their home created an "outstanding foster parent of the year" award, named it the "Lofton-Croteau Award," and gave the first one to Steven and Roger.

In July 1991, Steven got a call from a social worker asking him to accompany her to a private hospital to help her assess the needs of a biracial nine-week-old infant. The boy, whose name was Bert, had tested HIV-positive at birth and had been placed in a shelter home after his substance-abusing mother refused to care for him. A few weeks later, the state placed him in a foster home, but caring for the sick baby proved to be too much for the foster parents. Feeling desperate and not knowing what else to do, the couple had dropped the child off at the private hospital.

When Steven and the social worker arrived at the hospital, they were told that Bert was in an isolation unit and was being visited only by staff wearing masks, gowns, and latex gloves. The two visitors, however, refused to put on the protective gear and instead took turns holding the baby in their arms, sensing that the child needed direct contact with human skin.

As they were evaluating Bert's condition, a nurse walked into the room and said that the baby was ready to go. The perplexed visitors explained that they were there to assess the child's needs rather than to take him with them, but the nurse insisted that the boy could not remain in the hospital.

Not knowing what else to do, Steven ended up taking Bert home that night. The following day, the social worker called and suggested that Steven and Roger add the baby to their brood of foster children. After having Bert home for only a few hours, the couple was already smitten with love for him, and they quickly agreed to care for the boy as well.

A few months later, Steven and Roger enrolled all four of their foster children in a medical study of AZT, the first government-approved AIDS medication, at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). During the following four years, the family took more than two dozen week-long trips to the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, where the children received comprehensive medical testing and evaluations.

Despite Steven and Roger's best efforts, they were unable to keep all of their children alive -- in 1994, Ginger died when her fragile immune system was unable to cope with a bout of measles. Although the death of their 6-year-old daughter was devastating to the couple, they were to some extent comforted by the fact that a few months before her death they had learned that Bert had seroreverted to being HIV-negative. But once that happened, according to the Florida regulations, Bert became eligible for adoption. And when Steven applied to adopt the boy, the agency denied his application because state law prohibited gay people from adopting.

After officials began taking steps to find an adoptive family for Bert -- including showing up unannounced at his school to take pictures of him to show prospective parents -- Steven filed a federal lawsuit, with the assistance of the ACLU, arguing that Florida's adoption ban violated the Constitution.

There had been earlier unsuccessful challenges to the Florida law, but they were grounded in state constitutional claims. In contrast, Steven's lawsuit contended that the adoption ban violated his federal constitutional rights to due process and equal protection. The former claim was based on the notion that the state had encouraged him to establish a parent-child relationship with Bert -- at the time the lawsuit was filed, Bert had been living with Steven and Roger for almost nine years--and that the relationship was now subject to constitutional protection. The latter claim was grounded in the idea that it was irrational for the state to render all gay people -- regardless of background, experience, and personality -- ineligible to adopt.

In defending the law, the state argued that children were better off when raised by a married mother and father. This arrangement was particularly beneficial to children, Florida contended, because it allowed for proper "gender role-modeling." Only heterosexual couples, the state explained, permitted children to learn from both a male and a female parent.

Steven's ACLU lawyers responded to the state's claims by noting that even if the court were to assume that it was optimal for children to be raised by a mother and a father who were married, denying gay people the opportunity to adopt did not in any way help the state achieve that goal. This was because there were many more children in the Florida's foster care system waiting to be adopted than there were married heterosexual couples willing to adopt them. In fact, at the time the lawsuit was filed in 1999, there were over 3,400 children in Florida without permanent homes. And their wait for such a home was long -- almost forty percent of the children in foster care waited more than four years before being placed for adoption, while eighty percent waited more than two years. All of this meant that denying Steven the opportunity to adopt Bert because he was gay did not mean that the 9-year-old would be adopted any time soon by a married heterosexual couple. (A study conducted several years later concluded that Florida's gay adoption ban prevented an estimated 165 children in the state's foster care system from being adopted. Ironically, this was the same number of Florida foster care children who "aged out of the system" in 2006, that is, who became too old to be adopted.)

The state's claim that it took seriously the purported benefits for children of being raised by a married mother and father was also undermined by the fact that 25% of adoptions statewide (and 40% of adoptions in Dade County) were done by single people. (Nationally, about one-third of foster care children are adopted by single individuals.) And single people, of course, were unable to provide the dual-gender parental role modeling that the state contended was so essential to the well-being of children.

The inconsistencies in the state's positions were further evident from the fact that it permitted gay people to serve as foster parents and as legal guardians. (One of the other plaintiffs who joined Steven in his lawsuit was a gay man who several years earlier, with the state's approval, had been named a young boy's legal guardian at the request of the child's biological father.) Clearly, Florida did not really believe that placing children, sometimes for years, in the care of gay people was harmful to them. Indeed, the state seemed to reserve that contention only for when it found itself in court defending the constitutionality of its gay adoption ban.