IT'S ONLY A GARTER SNAKE, dusty brown with rows of black splotches running the length of its slender body. But the faithful who see it writhing on the concrete barn floor of this makeshift church, where snake handling isn't a part of the service, are justifiably jumpy: A 6-year-old girl was bitten on the foot by a rattlesnake just a few weeks ago, not far from here on the west side of Colorado Springs, Colo., near the United States Air Force Academy. As the snake slithers erratically through the barn, past three large gray buckets stacked waist high to serve as a lectern, past a hand-painted two-by-four reading "no stone zone," and finally past our feet, a young woman yells, "Whoa! Whoa! Whoa!" in rapid fire.

Scenarios like these almost always produce a willing hero: An elderly man with thick glasses bends down and grabs the snake just below its head. Triumphant, he walks it out of the barn and into an adjacent field to relieved applause, followed by a smattering of jokes -- variations on a theme of an obvious metaphor just witnessed by the new congregants of St. James Church, led by Pastor Ted Haggard.

We take our seats and wait for Haggard to finish greeting churchgoers as they drive down the circular paved driveway on Old Ranch Road leading to his home. The setting is instantly familiar to anyone who paid attention to Haggard's scandal, or "crisis," as he sometimes refers to it, in 2006. Recall Haggard, then head of New Life Church, in the maroon pickup truck, wearing a blue checked shirt and khakis, as he spoke to a 9News Denver reporter, denying his involvement with Mike Jones, a former gay escort in Denver who now works as a nursing assistant. Haggard spoke with conviction: "I did call him...I called him to buy some meth, but I threw it away.... I went there for a massage." Haggard's wife, Gayle, sat in the passenger seat, wearing a pale green sweater. She stared at her husband while he dug himself deeper before driving off. Four years later, in her memoir, Why I Stayed: The Choices I Made in My Darkest Hour, she wrote of the moment: "As we approached the traffic light nearest our house, his confident expression melted, and his forehead dropped to the steering wheel. When he spoke again, his voice came out in tatters: 'What have I just done?' [Haggard asked.] 'You just lied,' I answered, my tone flat. 'And everybody's going to know it.' "

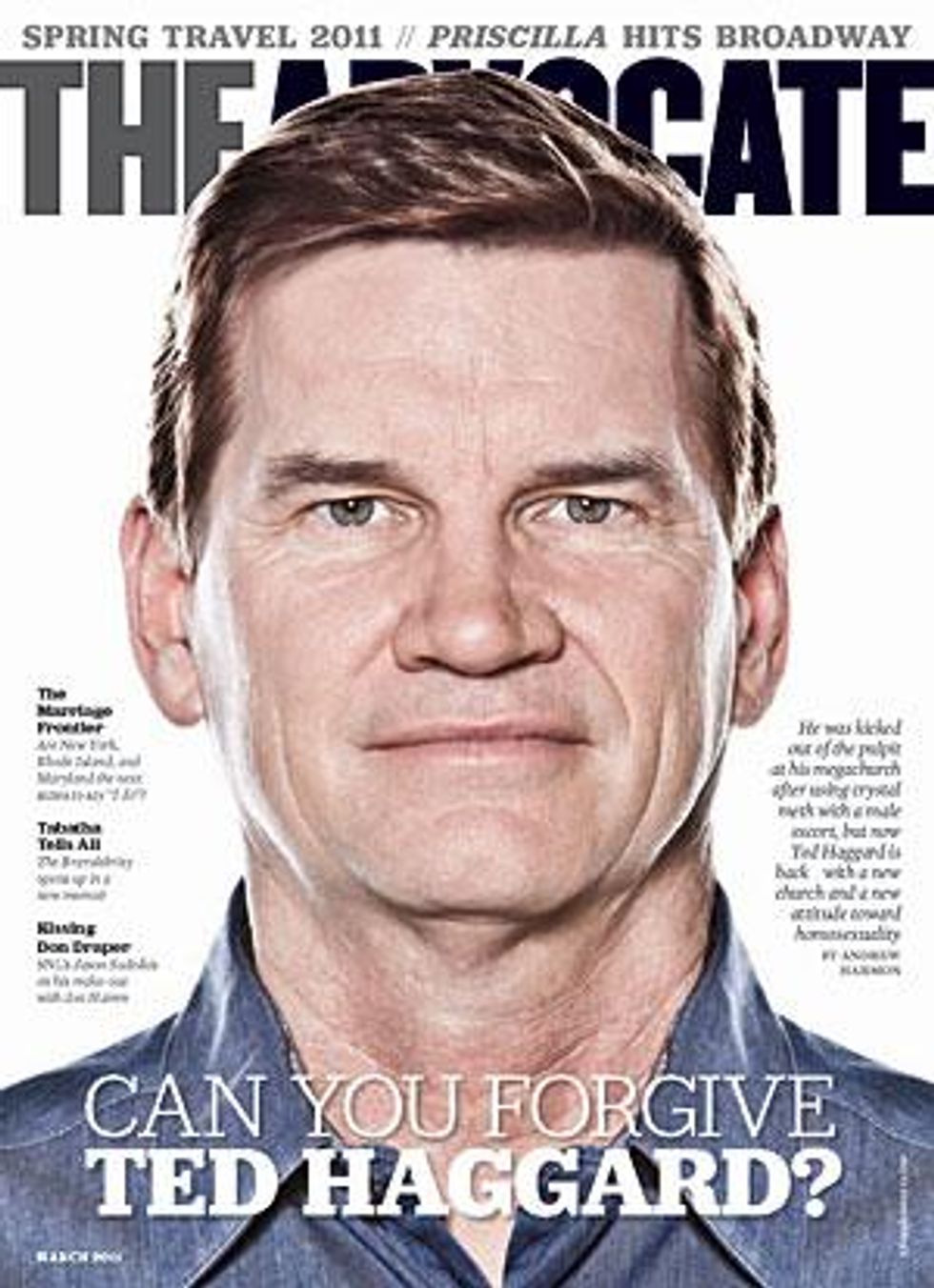

Everyone did, of course. And yet the man who, fairly or not, has come to embody the evangelical hypocrisy that gay people and their allies rail against daily -- whose name comes up every time a man of the cloth or an antigay activist is accused of a same-sex dalliance -- has returned to the pulpit.

Perhaps it's no surprise. Ministry is all Ted Haggard has ever known.

When I first spoke with Haggard, he was on his cell phone, pacing in the barn a few steps from his home, and seething about a story that had just broken in the news. It was May 2010, only a few days after the Miami New Times published an expose on George Rekers, a University of South Carolina emeritus professor, a founding board member of the Family Research Council, and a proponent of "ex-gay" reparative therapy who was caught with a 20-year-old escort from Rentboy.com. The young man, Rekers explained, had been hired to carry luggage for him during a 10-day European trip. The timing was terrible for Haggard, who was in the early stages of opening a new church and once again found himself in the news, as journalists compared him to Rekers. "I know exactly what it feels like to have both sides hating you bitterly," Haggard said about Rekers. In the background I could hear what sounded like his sneakers squeaking as he paced on the concrete floor. "But I'm not him. I was never hateful.... And let me emphasize: I've never been through -- what do they call it? Reparative therapy? Restorative? Whatever it is. The thing that they say people who are confused sexually go through. I don't know anything about it."

Two months later, at this Sunday service, Haggard's a completely different man than I heard on the phone. "All right, let's get started!" he says with his Cheshire-cat grin as he strides into the red barn in a striped button-down shirt. St. James is a far cry from nearby New Life, which Haggard and his wife started in 1985 and which, by the time they left, had grown to include 14,000 members. Today, only a few dozen people are arranged in semicircle rows of folding chairs to hear Haggard's sermon.

He starts things off with a testimonial from Kathy, a woman who sits in the front row with her teenage son and speaks about recovery from drug addiction. St. James attendees gave her a place to stay until she was able to find her own apartment. The mantra of St. James is "Give someone a break."

He starts things off with a testimonial from Kathy, a woman who sits in the front row with her teenage son and speaks about recovery from drug addiction. St. James attendees gave her a place to stay until she was able to find her own apartment. The mantra of St. James is "Give someone a break.""How long have you been sober now?" Haggard booms.

"About 44..." Kathy says.

"Just about five weeks sober, right?" he interrupts.

"No. Wait. Yeah," Kathy says.

"From meth and heroin." Kathy nods, beaming as the congregation claps.

Next to Kathy sits Daniel, a thin, 36-year-old man with blond hair who used to get high with Kathy and is also trying to kick a meth habit. He says he's been sober "about a week or so" and is also looking for help with work and a place to stay.

"So not quite a week," Haggard says. "You've got to tell the truth if you're going to do this, OK? If you do your work, we'll give you a break."

The "saints," as Haggard refers to them, are a lively and bighearted group, not exactly the lepers of Colorado Springs -- even though Haggard likes to think of his flock as progressive misfits in the heart of American evangelicalism. Most are conservative Republicans. There are dentists, homemakers, soldiers, and executives as well as drug addicts seeking salvation. "This is an exclusive group in Colorado Springs, you know," Haggard tells the faithful with a smirk. "But don't worry, this barn is perfectly safe. As long as the wind doesn't blow."

Later, at an after-service barbecue in the backyard, I tell Haggard about the snake as he mans a popular snow cone machine on the deck. "I heard about that! Of course, you have to start your article there, don't you?" he jokes, again with the smirk, one equal parts amusement and a resigned mistrust of most anyone writing about him. I'm always struck by how he speaks. His lips thrust forward, his white teeth invariably on display -- Haggard is the same in person as he is on Larry King Live or The Oprah Winfrey Show. He is instantly likable, his charisma knows no bounds, and he has a way of making you forget the details of his story. But then again, there's no way the members of St. James don't know what they've signed up for.

Reinvention after a public sex scandal isn't easy, but it's increasingly predictable. Eliot Spitzer now jousts with conservative journalist Kathleen Parker on his own CNN show. Golf aficionados hail the competitive comeback of their sun king, Tiger Woods. Perhaps John Edwards read Woods's November mea culpa in Newsweek ("How I've Redefined Victory"), looking for ideas. Show a little humility and America can be a forgiving, if amnesiac, audience.

The red barn, the snow cone machine, the same stacked-paint-buckets-as-lectern used to start New Life in a basement -- these are the humble props of Haggard's own comeback. Since I first visited him last summer, his church has outgrown the barn and moved to the auditorium of a Colorado Springs middle school, just three miles away from Focus on the Family's headquarters. A congregation of a few dozen has grown to a few hundred, and the portion of the offering dedicated to church members who have fallen on hard times, or are close to those who have, was $4,000 one recent Sunday (an instructor at nearby Everest College was the grateful recipient, and gave the money to several students who had been living in their cars while in school).

Forget where Haggard was, and that this 54-year-old father of five and grandfather of two once headed the 30 million-member National Association of Evangelicals and spoke to Bush White House liaisons on a weekly call of conservative religious leaders. Unlike the meticulous rehab script Tiger Woods is following, there's a naivete to the manner in which Haggard is building St. James. He's creating it from the ground up, hoping that his followers will prosper in tough economic times, trusting that the skinny man with blond hair will spend the small wads of cash church members give him on something other than crystal meth.

"People actually came up to me and said, 'I want to give you some money to hold for Dan, because he may misuse it,' " Haggard says. "And I said no. He's got to make his choices, and if we end up enabling him, such is life. And if we end up rescuing him, such is life."

A day after the barn service we meet at a Starbucks in Breckenridge, a resort town 100 miles northwest of Colorado Springs. We sit on the bank the Blue River, which gurgles parallel to Main Street, and later eat lunch at Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. Haggard arrives on a Suzuki scooter after Gayle, unfailingly kind and warm, set up the meeting over the phone. At the barbecue she had spent more than an hour signing hardcover copies of her memoir under a large locust tree next to the swimming pool. Churchgoers took books by the armful from neatly stacked cardboard boxes for her to inscribe, all courtesy of the Haggard family. It made for an odd scene: a woman's account of her journey with a husband many still believe to be homosexual, circulating through an after-church social in a backyard full of charred hot dogs, grape snow cones, kids playing in the pool, and parents eating off paper plates resting on their laps. Gayle signed her crisp signature again and again, chatting with everyone who approached.

"We were lonely," Haggard says of their decision to start St. James within eyeshot of New Life. "We wanted a group of believers, so we thought, if we start something and they choose to come, then they've accepted me." He later adds, "And we knew we had to finish the story, so it wouldn't finish with the scandal. So to finish the story, this is the place to do it." He says he got that idea from Alexandra Pelosi, the documentary filmmaker and director of HBO's The Trials of Ted Haggard. "She said, 'OK, let me just tell you in a language that you can understand: Jesus ministered and was crucified in Jerusalem. If he had resurrected in Rome, it wouldn't have worked. Although you deserved your crucifixion, you've got to resurrect in the same city where you ministered.' " A few weeks after the Rekers story broke, Haggard held a press conference to unveil the new church, speaking to reporters outside the barn in front of a real lectern. It was part expert self-promotion, part olive branch to the gay community -- or at least that's how it seemed. Whether you are "gay, straight, bi, tall, short, whether you're an addict, a recovering addict, or you have an addict in your family," you have a home at St. James, he said. After all, who's in a worse position to judge others on sexual matters than Ted Haggard? But sexuality and addiction spoken in the same breath is always troubling. And reporters needled Haggard about whether he would affirm same-sex marriages. "God's ideal plan for a marriage is the union of a man and a woman," he responded.

His position on marriage equality is a little more nuanced than he let on at the press conference -- and, like President Obama's, it seems to be "evolving." Many people remember Haggard's cameo in the 2006 documentary Jesus Camp, where he said, "We don't have to debate about what we should think about homosexual activity. It's written in the Bible." Today, he says his words were taken out of context, that he was speaking to a group of believers about Scripture, not making a statement on what should or should not be inculcated into law. In 2006 he supported Colorado's Amendment 43, which banned gay marriage under the state constitution, though he also supported a failed proposition that would have granted domestic-partnership rights to gays and lesbians.

Now Haggard wants to be clear: He supports civil marriage rights for gay couples. "The word marriage is a big deal to people of faith," he says. "We've made it sacred. That's why I believe that churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples should have total freedom to have whatever types of unions they believe as godly. But I think that we as a democratic society, as a constitutional republic -- if we don't respect individual civil liberties, then we're making a horrific mistake. The church is in the early stages of another 'the earth is flat' crisis. I say to all religious people that we should be quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to become angry on the subject. Or we're going to be embarrassed in another 10 or 20 years."

At the table behind him, a middle-aged couple wearing polar fleece jackets audibly tsk at that remark. They hadn't spoken a word to each other while waiting for deep-fried jumbo shrimp and are now stealing glances and whispering. Gayle has just called Haggard's cell to check in, and he doesn't seem to notice the couple as I wonder what it's like to be despised on so many fronts.

Many who have joined Haggard at St. James face similar tsks among the Colorado Springs faithful. "The religious community can be very unaccepting in my view. I think he's considered a threat to them, to be honest," says Randy Welsh, a former lead elder at New Life who joined the church in 1993. "But he's reaching an audience of people who largely don't go to church, who may be hurting and in need of some help. They don't have anything to lose. Most people who have something to lose have difficulty relating to Ted."

Welsh, a former CEO for a software company, now attends St. James as well as other area churches. He says he's seen a definite change in how Haggard operates. "He was a little too full of himself, a little arrogant, a little overconfident in his own abilities back then [at New Life]," he says. "He was more apt to use people for his own purposes rather than to help people. But the walls are down now. Now he's more of a real person, more humble, there's no question about it. Best I can tell -- and I probably know him as well as anyone -- there's nothing else in his closet."

Haggard's closet is a popular topic of conversation. In 2007 a New Life overseer who was in communication with Haggard during his post-scandal "restoration" declared him to be "completely heterosexual" after a few weeks of intensive therapy (not "reparative" therapy). Haggard tempered that assessment in 2009, saying through therapy he discovered that he is "heterosexual but with issues." He underwent eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, a common form of treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. EMDR has been championed by some ex-gay therapists, though the EMDR Institute is agnostic on such uses. Haggard says that through EMDR he was able to deal with the trauma of childhood sexual abuse and says he hasn't since engaged in any same-sex sexual activity.

"I've had the thoughts and the desires sometimes -- but never something compulsive since," he says. Probe further, and Haggard retreats a bit. He has firm talking points about Grant Haas, the former New Life volunteer who came forward as the Haggards were doing press interviews for The Trials of Ted Haggard in 2009. Ted had sent "inappropriate" text messages to the young man and masturbated in a Cripple Creek, Colo., hotel room that they shared during a field trip. "I'd appreciate it," he says, "if you remember that there was never any sexual contact between us, nor was their any contemplation of sexual contact on either of our parts." The sexual details of his life are now a matter between him and his wife, he says. He prompts a final scowl from the couple behind him when he adds that his marital intimacy is "vibrant, very satisfying."

It's easy to see why people conflate Haggard with leaders of the ex-gay movement, such as Exodus International's Alan Chambers, who describes himself as a "former homosexual" who still has same-sex attraction but keeps it in check and is happily married with children. "We're all going to struggle with something," Chambers told me last year, in a manner reminiscent of the "heterosexual but with issues" idea. "You come to Jesus and all of it doesn't get taken away 100%. Whatever 'all of it' is. We're a group of people who, regardless of the level of those attractions that we have, regardless of the temptations that we have, regardless of where we find ourselves in that struggle, we're a type of Christians who believe the traditional view of sexuality."

Nevertheless, the ex-gay movement has faced some embarrassing setbacks over the past year or so. The Rekers scandal made national headlines. (As Frank Rich wrote in a May op-ed for The New York Times: "Thanks to Rekers's clownish public exposure, we now know that his professional judgments are windows into his cracked psyche, not gay people's.") There was also the story of Ryan Kendall, a 27-year-old NCIC agent for the Denver Police Department and Colorado Springs native who testified in the high-profile Proposition 8 trial about his past experience under the care of National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality cofounder Joseph Nicolosi -- how ex-gay therapy compounded his already dire circumstances as a vulnerable teenager living with a family who renounced him for his sexual orientation. All the while, Nicolosi's "model" client, a man named Kelly said to be "cured" of homosexuality, frequented gay bars, Kendall testified. In the summer of 2009 the American Psychological Association adopted an updated resolution calling reparative therapy potentially harmful and lacking in evidence as to its purported benefits. Michael Bussee, an Exodus cofounder who ultimately left the group, echoed as much in an April video. "I never saw one of our members or other Exodus leaders or other Exodus members become heterosexual," he said.

But Haggard isn't out to change anyone's sexual orientation. He thinks gay people can thrive at his church, which he believes has the power to change Colorado Springs: "No, I don't believe you can pray the gay away," he says. I saw the NO STONE ZONE rule duly enforced -- at least within the walls of St. James. Outside that zone Haggard lobs plenty of criticism at the evangelical powers-that-be, those who he has always thought were out to get him. "They'll always think I'm a closet homosexual. And they hate homosexuals, that crew," Haggard says of conservative para-church ministries. He readily names a list of culprits, including the Christian Broadcasting Network and Focus on the Family: "The number 1 way they can raise funds is not to encourage people to be more loving, not to encourage people to be less greedy, or to encourage people to be more kind. It's to say there's a secret homosexual agenda to siege America, and fund us so we can battle this agenda, to save the family."

Is his message being heard? Or has Haggard lost all credibility? Whatever his impact, there are subtle signs of change within the evangelical world, though nothing close to widespread support for marriage equality: A 2010 Pew Research Center poll showed that 74% percent of evangelicals oppose civil marriage rights for gay couples. While the Family Research Council continues to take a hard-line stance against equal rights for gay people, Focus on the Family president and CEO Jim Daly has soft-pedaled the group's antigay rhetoric, once trumpeted by Focus founder James Dobson, who resigned as chairman in 2009. Where Dobson attacked the political left and was eager to take on socially charged issues such as homosexuality, Daly has praised President Obama as a model family man and prefers less incendiary topics: how to raise kids who will behave, for example, or how to build a solid marriage when one's partner is of a different faith.

"That's not to say that Focus and groups like it are changing their views on same-sex marriage," says David Masci, a senior researcher at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (indeed, Daly criticized Obama in June for recognizing gay dads as part of a Father's Day proclamation). "Instead, I think Focus has placed a little less emphasis than it once did on this fight."

As for the Haggards' ministry, "If there's progress, it's probably more for them than for anybody in the LGBTQ community," says Jay Bakker, a pastor and son of Jim Bakker and the late Tammy Faye Bakker Messner. Like Haggard, Bakker has a beef with evangelical opportunism when it comes to gay issues. Where they part ways is in Bakker's wholehearted embracing of gay relationships as spiritually equal at Revolution Church NYC, his Brooklyn, N.Y., ministry. "Ted having this fall and being restored is pretty amazing," Bakker says. "And I think what we're seeing is part of a slow process of the church coming around. Unfortunately, I don't think [St. James] would be a healthy place for someone whose sexual orientation can't be accepted. I mean, it's common: 'We'll welcome anybody -- until they want to be on staff or have a commitment ceremony.' To me, oppression is oppression."

Mike Jones, the former masseur and escort who took down Haggard, goes it a step further: "To me, the gay community should still be outraged. When you look back at some of the things [Haggard] said, that he considered [homosexual acts] to be his dark side, how does that make you feel as a gay man?"

Haggard's resurrection has garnered no shortage of ink or film footage. He tells me he is loath to speak to the media now. But his multiple cable news appearances -- most notably last fall, after Georgia megachurch leader Eddie Long was accused of coercing four young men into sexual relationships -- tell a different story. I find out from Jones that another national magazine is working on a piece about Haggard, and as this article went to press in January, cable network TLC announced it would premiere a one-hour special on St. James as the Haggards launch "a new ministry unlike any other church ever seen."

As Jones sees it, he's become a forgotten part of Haggard's story. When he tried to appear on Oprah to tell his side of things, he says, the show's producers told him he was irrelevant. Many of his family members no longer speak to him. His 2007 memoir, I Had to Say Something: The Art of Ted Haggard's Fall, drew only two people to a book-signing event.

"When my world was collapsing, when the media was knocking at my door, I really felt abandoned by the gay community," Jones says, though he also says he's not looking for pity. "I have fought for gay rights all my adult life. People said I did this for the notoriety and money. What money? I've been dirt-poor since this happened. I regret I ever said anything. It has simply not been worth it."

Jones now works in Denver with the elderly, many in the late stages of Alzheimer's disease. "I have to wipe some butts and clean up vomit once in a while," he says. "But this is my way to give back to humanity."

The first day of 2011 brought near-zero-degree temperatures and bitterly cold winds to Colorado Springs, but January 2 is a little warmer. Road salt melts the snowpack on the streets as the faithful drive to Sunday services. The sun is blinding, and the view west toward Pikes Peak is resplendent. One can easily see why Ted Haggard, camping by himself on the 14,115-foot-tall mountain in 1984, divined that a year later he would build his church nearby.

New Life is abuzz. The hexagonal worship center is filled to near capacity for the 9 a.m. service, with a few front rows reserved for families with newborns waiting to be blessed. A dozen musicians energize the crowd with 30 minutes of nonstop Christian rock, the lyrics projected onto a gigantic screen. It's the kind of music you might find grating when you're stuck with it while driving an isolated stretch of highway, but here it's hard not to at least tap your foot. There are no overt signs that the Haggards once belonged here. Why I Stayed is nowhere to be found in the church bookstore among titles on Sarah Palin and a memoir by Tim Tebow. I ask a man at the espresso bar whether Haggard ever visits and he briefly looks at me as though I've requested Eucharist wafers to go with my decaf. Then he softens. "You know, we do wish Ted the best," he says.

Scott Miller, a local chiropractor, used to attend New Life with his wife and two children, but now finds himself at St. James's 10 a.m. service at Timberview Middle School, where there are no snakes to be found on the vinyl tile floor, just spills of coffee and Haggard's famous spiced apple cider. Scott is 39, divorced, openly gay, and here with two gay friends, Osie Barkley and Jean Mortensen. New Life is a little too slick for his spiritual tastes now, Miller says. The service is beautifully produced, the music is great, but it lacks a certain heart and an honesty that St. James has. He's now working on creating a national project called the Reconciliation Conversation to build dialogue between Christian leaders and the gay community, and he's hoping Haggard will be an integral part of that.

"I believe there was a shift in the city when all of this happened," Miller says of the scandal. "When Ted became human to us, then I think many people began to realize there is no perfect place to be, that we need to make amends with those we've hurt. I kept seeing people change their hearts. So I don't know on a big political level, but I know that for a lot of people the walls began to crumble and forgiveness began to happen.... I do believe that a gay person whose ultimate goal is not to become straight can grow and be welcomed at Ted's church."

Today, in lieu of a sermon, Haggard and his wife sit for a Q&A with churchgoers, who wrote questions down on index cards and passed them to the front. Even the fairly innocuous queries elicit humorous responses from the couple:

"How long have you been married?"

Gayle: "32 years."

Haggard [smirking at Gayle]: "And it's been a perfect marriage. We've never had any problems. It's perfect."

Gayle [smiling back]: "I've said this before: When Ted asked me to marry him, he promised me adventure. And he has delivered."

They make a good team. Haggard the showman, the consummate preacher; Gayle the keen nurturer. They may still be cultural punch lines, but if they were your neighbors, you wouldn't hesitate to invite them over for a backyard barbecue. Later Haggard goes on to rail against evangelicals using their power to oppress those who are not like them, imploring instead that Christians must advocate for "equality, constitutionality, and law." He points at a Caucasian man sitting with his Asian wife in one of the back rows. "People argued for years using the Bible that folks like yourself, a Vietnamese man and a Caucasian man, shouldn't be allowed to marry. It's ridiculous!"

The crowd laughs and murmurs. " 'Woman!' You mean 'woman'!"

Haggard stops and grins. "Never, ever, ever quote what I say. Quote what I mean."

After the service there are enchiladas, refried beans, tortilla chips, Dr. Pepper and Coca-Cola. Haggard sits with Scott, Osie, Jean, and me for lunch, and I ask whether he thought he might come to embrace gay marriage within his own church, to perhaps one day sermonize about a gay couple the same way he had just spoken, however fumblingly, about an interracial couple. Haggard mulls it over for a second. "I'm a bit timid in that respect. It's my job to teach people to be responsible, without me being the center of it. And it's all our responsibility to protect the rights of people who are not like us."

Later that afternoon I text Haggard and thank him for having me at his service. It was as he promised: an exuberant Sunday morning for an imperfect group, led by an imperfect man. And the spiced apple cider was excellent.

A few minutes later he responds. "Come on, Andrew, move to Colorado Springs and help me with St. James. That would be so much fun. You can help because of social concern, and I can beat the Bible thing. It would probably be good for both of us. :) Love you my friend! Ted"

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.