Embracing the spotlight is nothing new to Broadway star Robin de Jesus. Since winning the hearts of theater geeks across the country for his role in the 2003 film Camp, playing a gay teen who gets beat up for wearing a dress to prom, the out actor has become a fan favorite among New York City's theatergoers. In the process he's created a unique persona on and offstage, crafted by passion, grit, and a yearning for truth.

His roles as Sonny in Lin-Manuel Miranda's In the Heights and as Jacob in La Cauge aux Folles earned him Tony nominations. He's received rave reviews for his role as Boq in Wicked (on Broadway and the International tour), and now he's returning to the stage for the 50th anniversary production of The Boys in the Band, opening on Broadway May 31.

De Jesus's raw talent is palpable on stage. While the roles he plays have been unapologetically queer, it's the sheer honesty he displays that keeps audiences returning. As Emory, perhaps the show's most empathetic and least self-loathing character, de Jesus is fully aware the impact Boys left on a 1968 audience -- and he's equipping himself to enlighten a more evolved one of 2018. But that's no easy picnic.

The Advocate: Do you remember the first time you saw or heard of The Boys in the Band?

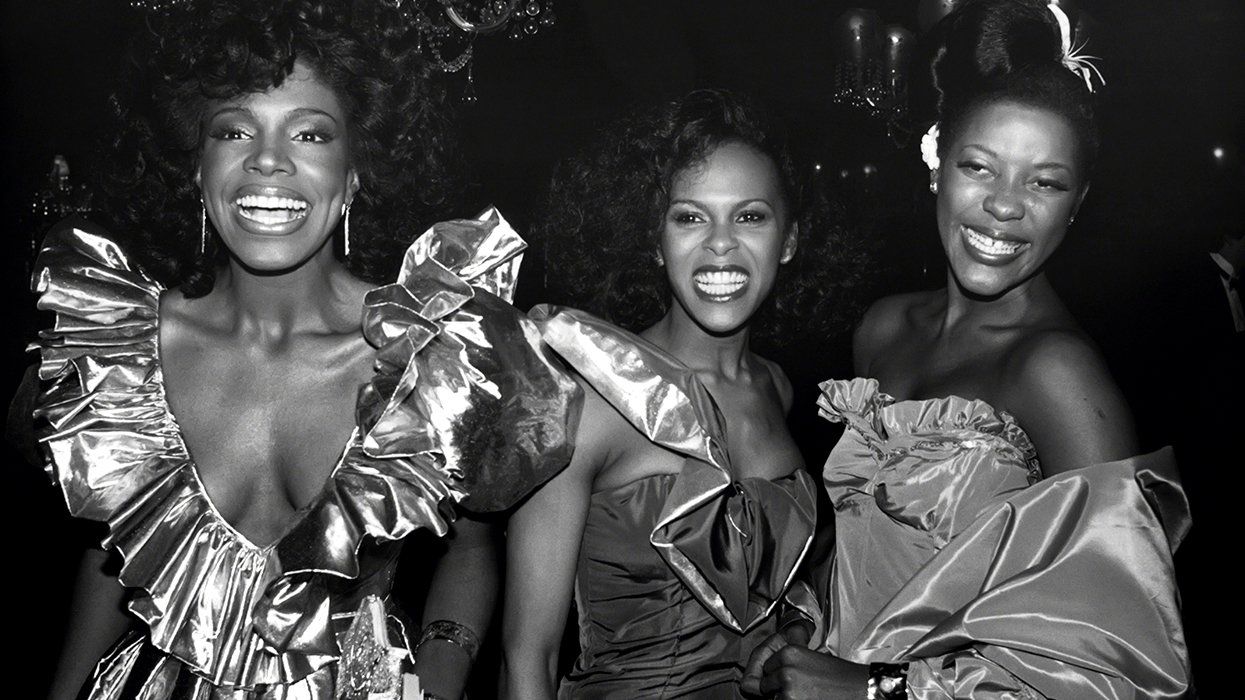

Robin de Jesus: I saw the movie. I have never seen the play, although years ago I had read it. My experience in the past with the piece was that it felt kind of dated. The imagery was amazing, watching the movie, because seeing a group of gay men in a period piece was like, "Oh wow, they existed." There's so much erasure of marginalized groups of people that are examples of certain religious groups or gays. Just to see the image of gay culture in that time period, it was very jaw dropping. But for some reason I couldn't really see what was truly going on.

I realized, everyone struggles with a story and what they've been through. But not everyone knows how to come out of those things. When you are part of an entire group of people who have all been told, "You're not worthy. You're not significant. You are no good," no matter how namaste you are, there's a part of you that's going to take some of that in. There's going to be some effect of that on you. It's going to trigger some shit. And so, how do you deal with that? I think that's what this play is about. I think it seemingly comes across as just men hating themselves. People have a hard time with that.

There is a certain degree of self-loathing in the play, which is stemmed from the social oppression of queer people at that time.

The play takes place in 1968, and to be a gay man in that time period means you're probably bound to stay in the closet. You can't tell people, or if you were courageous enough to come out, you were probably kicked out of your family. So you lost this group of people that had your back your whole life. Or those that you've loved the most now just disown you. And living in complete secrecy, which leads to shame.

How can you healthily interact with other human beings if you're living a life where you're constantly masking? You're constantly putting up walls. You're constantly not being genuine, not being who you really are. Being very performative.

The play has received criticism over the years because of the way the characters speak to each other. Do you feel that's not necessarily fair?

People who have harsh criticism of the play, I think what they don't understand is that it is a negative portrayal proving a point: this is the effect of all the baggage that's been put on us. So it's really saying, "Man, we're fucked up because we should be a part of everyone." We should be a part of the big picture. We should be a part of mainstream culture and we should believe that we're good and that we're made of good. That we have value and contribute to society.

For my character, Emory, he is hands-down the most flamboyant, effeminate one of the group. And in that time period, he couldn't hide that. Everyone instantly knew that he would be a "nelly." And so, for him, it's really difficult because who knows what his real life is like when he goes home. In my mind I just imagine Emory as a kid being constantly told, "Stop being a little pansy. Stop being a little girl. Act like a man." Having had that drilled into his brain.

We almost forget the courage it took for queer people to express themselves during that time.

One hundred percent. With Emory, [I wonder] how much of that is sheer courage and how much of that is he had no choice. He's not someone who can pass as masculine. He's not someone who is "masc for masc." He's not someone who can pass or pretend. He can only be himself. So there's a part of me that wonders where that courage kicked in, because at some point it was just, he couldn't help it. At some point I think he had to say, "I guess I just have to be me, because I have no choice."

Did you have an epiphany like that in your own life?

It's funny because I do a lot of work as a gay man playing gay characters. I've played a lot of drag queens and effeminate people. Every time [I play a queer role], my "Robin" baggage comes up, dealing with my masculinity because I am an effeminate man. As a kid... I would pretend and act a certain way -- gesticulate a certain way or not cross my legs. So I struggled with this PTSD for years, "Oh Robin, you're being too gay right now." Once again, masking. And every time I play roles like this, it brings it up, there's a resistance in me. I flash back to that stuff. For me, rehearsing Emory, I have to be like, "Bitch, you need to queen out!" The most masculine thing you can do is be courageous. Be that queer, gay, nelly boy. Live your life.

Our culture has arguably turned masculinity into an artificial thing. It's become a kind of aesthetic, so it's refreshing to see characters who don't play by those rules.

It's been boiled down to a superficial aesthetic, yes. I actually think what it is to be your most masculine is no different at all than what it is to be your most feminine. To me, they are synonymous. They are measured by your level of goodness, by your desire to be good, and your work effort, and your contribution.

People are attracted to that because people crave authenticity. They crave it. So when they see it live-action, they want whatever that is. To me I think authenticity is just trust-worthy. Like I'm willing to go along with you because I believe everything you say. I know for a fact I'm not being handed bullshit. Because with authenticity, it's not necessarily clean or pretty. It's just real.

Do you think social media has shifted our perception of what "real" is?

We're living in a world that's so artificial. With social media and Instagram, everyone is trying to make an image. So much so that they forgot what the truth is, in a way. I look forward to an implosion of that in our culture.

How cool would it be if social media ended up being a fad this whole time?

That would be amazing, but I think more what's going to happen the depression and anxiety is going to get crazy. We're going to be like, "What is wrong with us? We have got to figure out our stuff for ourselves." Because it's so strange, I feel there was a level of consciousness coming into all of us over the last 15 years, where society was becoming more aware of being morally responsible for each other and other groups that were different than us... and then came social media.

Social media crept up on us. The addiction is so real. It's so real. But it's a crazy addiction because you don't really get anything. At least with a gambling addiction there's a risk that you could possibly cash-in with something. But with this kind of addiction, it's only destructive as far as I'm concerned.

What's interesting is, I don't know what it will be like for my nieces and nephews, because they're younger and they've had [social media] in their lives more. I do notice that when I'm in a rehearsal space or when I'm on vacation or whatever, and when I take the time to consciously turn my phone off, and not engage with it, I don't miss it!

Do you feel the way queer men speak or treat each other has changed from 1968 to now?

What's really interesting now as a gay man is that there's so much more to us as a culture. We have so many groups and niches that the gay experience has more variety than it used to have then, I think. So for me, I find that my group, my gaggle of gays as I call them, they are wonderful humans, self-empowered human beings who fully support one another. We got each other's backs in the best way possible. But I do know of others.

When I go on social dating apps and I see something that's so prevalent, like "masc for masc," stuff like that where I'm like, "Oh I guess people are still dealing with this internalized homophobia." There is still shame... there are people still struggling with coming to terms with their sexuality.

There are people who don't have support systems. So certain parts of the struggle are very much real... It's interesting because my reality as an out gay man in New York is so different from the reality of an out gay man in Mississippi. So while I might not know first-hand all of the similarities to the culture during the time of The Boys in the Band and now, I know that it still does exist in certain communities.

How do you think we can be more accepting of each other as a society?

I think the big issue is that our culture, even as gay men, we only stick to what is similar to us. And generally, all America, if you [only] look at your group of friends and family and everyone who looks like you, you don't have a real perspective on life. If you lead a monochromatic life, then you probably aren't as empathetic or sympathetic as would be ideal. I think the best advice I can give to people is: Get to know people who are unlike you. Get to truly know them, get to really experience them, spend time with them, recognize that they have contributions to society you may not have thought of or that are different than yours, and also have value. What that does is it normalizes and it humanizes people and allows you to separate what you thought was them, versus who they really are.