I have a love-hate relationship with the term "nonbinary." When I first came out to my partner, I told him about the dilemma I was having.

"I mean, technically my gender is not binary, but that doesn't make for a very good term to lay an identity on."

I get that nonbinary is a useful umbrella term for all the ways that people exist outside of "man" and "woman" -- agender, demiboy, transfeminine, two-spirit, androgynous. Gender is incredibly complex. I also understand that for a lot of people nonbinary simply fits as its own identity, as the best term to describe who they are.

But I personally don't like the idea of centering my identity label on what I'm not. It's the same reason I'd never call myself "nonwhite." I want to celebrate myself for who I am: trans, genderqueer, Black. It's important to me to be specific.

I started my gender journey by exploring fashion. I remember the day in the fifth grade that my mom took me to Southcenter Mall, just south of Seattle, and bought me my first pair of baggy jeans. I admired the rappers on TV and tried to make myself in their image: sagging jeans, jerseys, snapbacks, and a fake chain.

I know that gender isn't just about what you wear, but that's how it started for me. I've gone through phases, back and forth between presenting more masculine and feminine over the years. But for the most part, I didn't question my girlhood.

But then something changed.

By age 26, I felt constant and overwhelming anxiety that at first, I didn't know how to name. I was angry at the way I was expected to be, how I was expected to look. At my office job, I thought looking professional meant wearing blouses and heels. Valentine's Day dates with my partner meant dresses and perfectly curled hair. I heard my grandmother's voice in my head telling me to be "pretty and poised."

I started to feel like I was two different people. On the outside, I was the spunky, stylish woman everyone knew, but on the inside, I was an angry Black man named Leigh stuck inside a body that he didn't want. Being a survivor of abuse, I've encountered a lot of angry men in my life. And for a while, I was one too.

Instead of letting the rage eat me inside out, I mustered the courage to tell my partner. At the time, I felt like genderfluid was the best term to describe myself. Some days woman, some days man, some days neither.

Knowing what it means to be a Black man in America is terrifying. On days when I presented as more masculine, I could feel the way people treated me differently. A middle-aged white woman clutched her purse as we rode up the escalator at a light rail station. I felt the eyes of police and security guards on me in public. I was scared knowing what they do to Black boys like me.

I couldn't do anything about the way people, especially cis white people, perceived me, but over time I got more comfortable being myself. Meeting other Black trans people in my community helped me be comfortable in my own skin. I got to see that we are beautiful, diverse, talented, passionate, gentle, and loving.

So what, on Trans Day of Visibility, does it mean for a genderqueer, genderfluid, or nonbinary person to be visible? When many people think of a nonbinary person, they imagine a white, thin, androgynous, or masculine-leaning person assigned female at birth. But there are a lot of nonbinary people, including myself, who don't fit that image. As such, those who are Black, fat, feminine, or assigned male at birth are often made to feel invisible as nonbinary people.

But for others, like Black trans women, transmisogyny makes them hyper-visible and usually the main target of transphobia. We see this in the disproportionate violence that they face simply for being who they are. We see this in the wave of anti-trans bills, including in my home state of Washington, seeking to ban trans girls from sports and bathrooms.

The argument that the opposition uses against trans girls' "advantage" in sports sounds a lot like what "scientists" used to say about Black people. Because of our "biology," we run faster and are better at basketball. I imagine these "scientists" measuring our legs, our muscles, our hands, trying to prove our unfair genetic superiority.

On both fronts, race, and gender, the message from the opposition is that we don't belong. Gender is a social construct defined by the culture you're in, but what does that mean when you're Black in America and racism tells you that you don't fit? For Black trans people, this means it is crucial for us to carve out our own spaces.

I recently attended a workshop called "Genders of the Future: An Introduction to the Black Genders Archive." It was beautiful to be in a Zoom room full of Black people of different genders talking about what it means to explore gender from an Afro-futuristic lens. Since then, I've been rolling these questions around in my mind: How do I define my gender in a way that is expansive, not confined to the ways that mainstream Eurocentric American society tells me my transness should look? How is my gender distinctly Black?

I am learning what it means to stand in my truth, to be so undeniably joyful, Black, trans, and proud that others can't help but see me. Important to be visible in all our complexity to show trans people, especially those who aren't yet comfortable being who they are, that we exist, we are diverse, and there is more than one way to be trans. And I hope everyone sees us, cis and trans, and knows that it's OK to love and celebrate who we are.

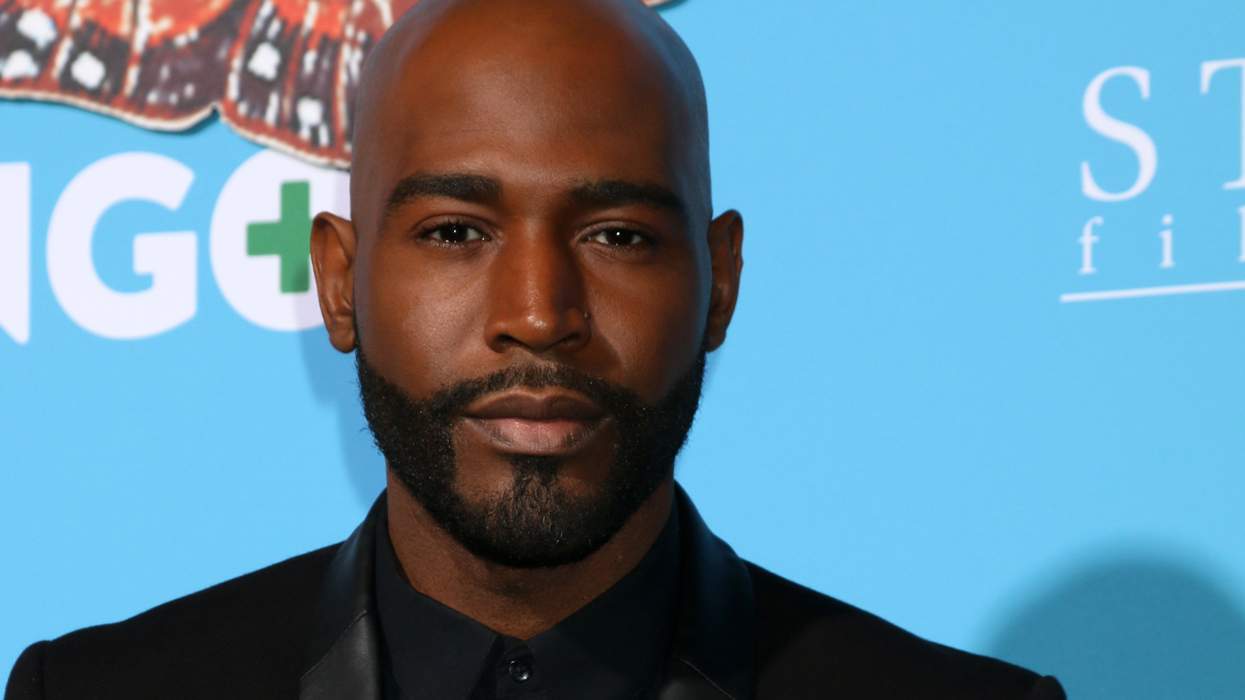

Leroy Thomas (he/they) is a Black, queer, and trans artist, and creator as well as the director of communications at the National Center for Transgender Equality.