CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

A few weeks ago, America witnessed a tragedy in Tucson, Arizona. A mentally unstable young man used a semiautomatic handgun to kill six people and wound sixteen at a parking lot town hall meet-and-greet in the district of U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords. Rep. Giffords, the shooter's intended target, took a bullet to the head and is recovering at a rehab facility in Texas. Others, including a 9-year-old girl, lost their lives.

Within hours of the shootings, there was a swarm of criticism focused on a map posted months earlier by Sarah Palin, in which the former Alaska Governor placed gun cross hairs (or "surveyor marks" as Palin staffers have since insisted) over a handful of congressional districts, including that of Rep. Giffords, urging followers to "take action" ... though exactly what action was not entirely clear. Opponents pointed to Palin's rhetoric, which includes the entreaty, "Don't Retreat! Reload!"

The criticisms cooled, at least marginally, when investigators found no evidence in the shooter's blogs and Facebook postings that his attack was either politically motivated or influenced by Mrs. Palin's choice of words and images. Palin supporters cried foul at the somewhat partisan criticism of their leader, pointing to how little hubbub occurred following a speech made by Obama during the 2008 campaign in which the then-Presidential hopeful urged his own supporters to meet GOP challenges aggressively: "If they bring a knife to the fight," Obama told his audience, "we bring a gun. Because from what I understand, folks in Philly like a good brawl."

A political and social debate has risen. Four days after the Arizona shootings, Mrs. Palin and President Obama each offered comment on the events, she from her Facebook page via video, and he at a televised memorial service in Tucson. The two politicians took remarkably different approaches:

Posted first, Palin's speech was defensive and defiant, placing herself at the center of matters and, to the dismay of leading Jewish organizations, potentially heightening tension by using the term "blood libel" to describe her treatment by mainstream media and commentators. (Blood Libel is a description of lies and distortions used by Nazis and other anti-Semites during World War II to whip up sentiment against Jews and justify the Holocaust.)

That evening, Mr. Obama spoke more broadly and gently, using the language of grieving, echoing to an extent President Reagan's address to the nation after the Challenger disaster and President George W. Bush's impromptu Ground Zero speech following the events of 9/11.

Current polls show Americans divided on the question of whether responsibility for the Tucson shootings should be shouldered by Mrs. Palin and others who have engaged in political speech laced with violent or inciting references. (President Obama's earlier remarks have not played a large role in the discussion.) Getting perhaps the most criticism are politicians aligned with the Tea Party movement, including Nevadan Sharron Angle, who, in the lead-up to the 2010 elections, suggested her followers look to "Second-Amendment remedies" (referencing the right to bear firearms) in response to politicians and policy with whom or which they disagreed.

As public opinion about the Tucson shootings solidifies, one thing is

certain: the President's ambassadorial response resonated with Americans

while Mrs. Palin's recalcitrance did not. Seventy-eight percent of us approved of Obama's

handling of the tragedy, according to an ABC News/Washington Post poll,

while just 30 percent gave Mrs. Palin a similarly favorable report.

The

question of whether rhetorical antipathy, clearly evidenced on both

sides of the political aisle, influenced the shooter to commit his

crimes may ultimately prove to be less useful than how such rhetoric

affects politics overall. Also worth exploring is how we interact, both

in politics and in day-to-day dealings, with others with whom we

disagree and how that affects our political and social landscape.

I

was thinking about all this the week after the shootings as I went to a

benefit for the American Foundation for Equal Rights, the organization

that put together the Prop. 8 legal "dream team" of attorneys David Boies

and Ted Olsen. Elton John performed a set of songs at a sprawling

estate in Beverly Hills for an audience of big-dollar donors. That

evening, $3 million was raised for the fight to overturn

California's Prop. 8, which makes same-sex marriage illegal. Near the end

of his performance, Sir Elton turned to the audience and spoke about

how he's been with his partner David Furnish for 17 years, how they have

adopted a child together and still cannot marry in California or his

native Great Britain.

"I don't have everything," he said, "because I

don't have the respect of people like the church or politicians who

tell me that I'm not worthy, that I'm lesser because I'm gay. ... Well,

fuck you. Fuck you!"

We gave him a standing ovation for that one. Our outrage had been voiced. Our applause and hooting was a visceral response to our years, indeed decades, of subjugation. The next day, the newspaper headlines and blogs were blunt, and seeing the comment in print sobered me:

"Elton John: 'F**k You' if You're Against Gay Marriage," declared the website Popeater.com.

I realized how Sir Elton's off-the-cuff would play to a mainstream audience: not well. While much social change occurs through the actions of the nation's courts, such as the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision that integrated America's schools, the ballot box remains a significant determiner of our civil rights. And it's the votes of that mainstream audience which LGBT people and their allies may need, both nationally and state-by-state, to complete the marriage and civil rights puzzle. Furthermore, it'd be naive to suggest that our courts operate entirely outside the influence of political pressure and popular opinion. While America's judiciary has often acted to secure civil rights in advance of broader societal acceptance, the court still represents and reflects society.

So while Elton John's passion riled a sympathetic crowd, what did the resulting declaration do for the cause of gay marriage overall? One may argue it knocked us back a step, though I can't fault him for speaking his truth.

What is the take-away for those of us involved in messaging the struggle for same-sex marriage, the rights of gay and lesbian servicemembers, those fighting for employment non-discrimination and the rights our transgender brothers and sisters? Many of us feel like hollering out a Palin-like "Don't Retreat! Reload!" in response to Prop. 8. We itch to (and do) call groups like the National Organization for Marriage and the Church of Latter Day Saints vile names. It feeds the angry, indignant gnaw in our gut. There's similarly vitriolic, sometimes hyperbolic language in email blasts from major LGBT organizations, like Equality California, on whose Board of Directors I serve. This may shake loose some dollars by riling a donor base. But we are writing and speaking in sensitive times. And our words have repercussions, some obvious, others subtler.

We are in a struggle for our rights. And the way we will secure those rights is by winning the hearts and minds of what demographers call "the moveable middle"--a not-insignificant number of voters (family members, co-workers, congregants, neighbors) who are neither LGBT advocates nor intractably opposed to us living our lives authentically. These are the voters who we didn't win over the first time around. By calling them names, maligning their faith or labeling them bigots, we risk losing them for good.

This is a time for de-escalation, a laying down of both arms and rhetoric, and an embrace of that which is common, civil, and decent. America spoke its mind clearly in the polls following the Tucson shooting. Let us not turn a deaf ear to what the country and common sense are saying about our political and social messaging. Let us be the loving and tolerant people we purport to be, and perhaps we will be in a better position to expect the love and toleration we request from the world.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Here Are Our 2024 Election Predictions. Will They Come True?

November 07 2023 1:46 PM

17 Celebs Who Are Out & Proud of Their Trans & Nonbinary Kids

November 30 2023 10:41 AM

Here Are the 15 Most LGBTQ-Friendly Cities in the U.S.

November 01 2023 5:09 PM

Which State Is the Queerest? These Are the States With the Most LGBTQ+ People

December 11 2023 10:00 AM

These 27 Senate Hearing Room Gay Sex Jokes Are Truly Exquisite

December 17 2023 3:33 PM

10 Cheeky and Homoerotic Photos From Bob Mizer's Nude Films

November 18 2023 10:05 PM

42 Flaming Hot Photos From 2024's Australian Firefighters Calendar

November 10 2023 6:08 PM

These Are the 5 States With the Smallest Percentage of LGBTQ+ People

December 13 2023 9:15 AM

Here are the 15 gayest travel destinations in the world: report

March 26 2024 9:23 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

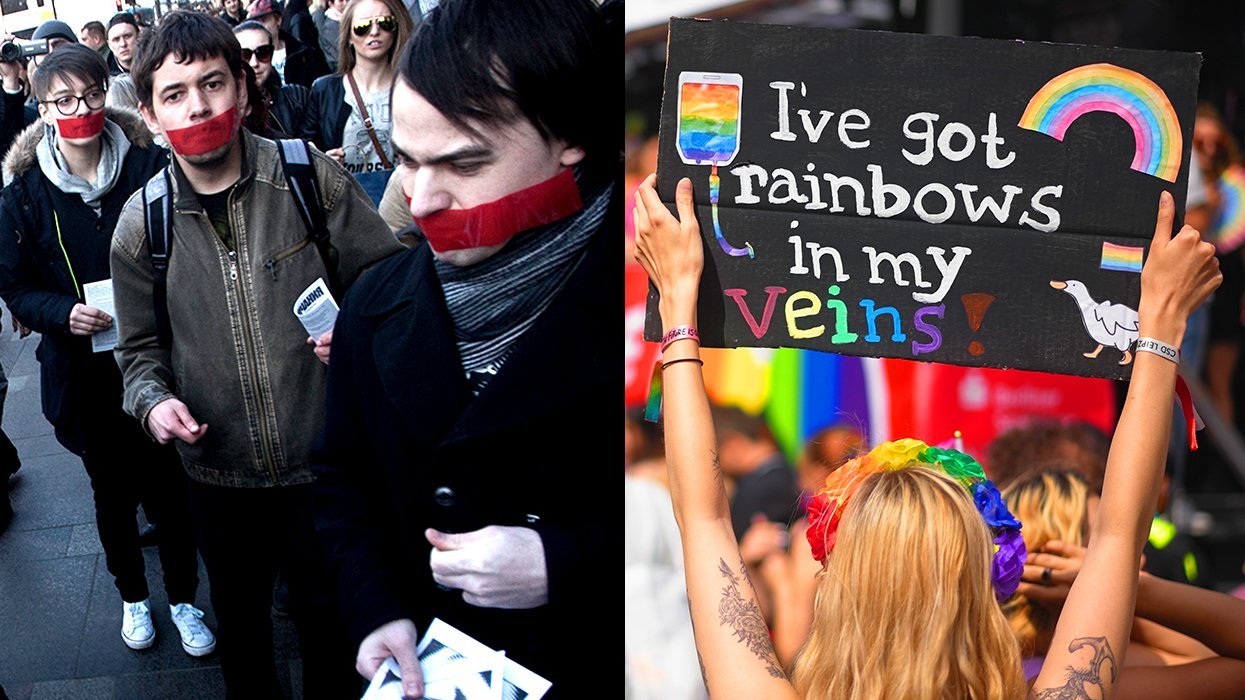

After decades of silent protest, advocates and students speak out for LGBTQ+ rights

April 13 2024 10:52 AM

11 celebs who love their LGBTQ+ siblings

April 13 2024 10:33 AM

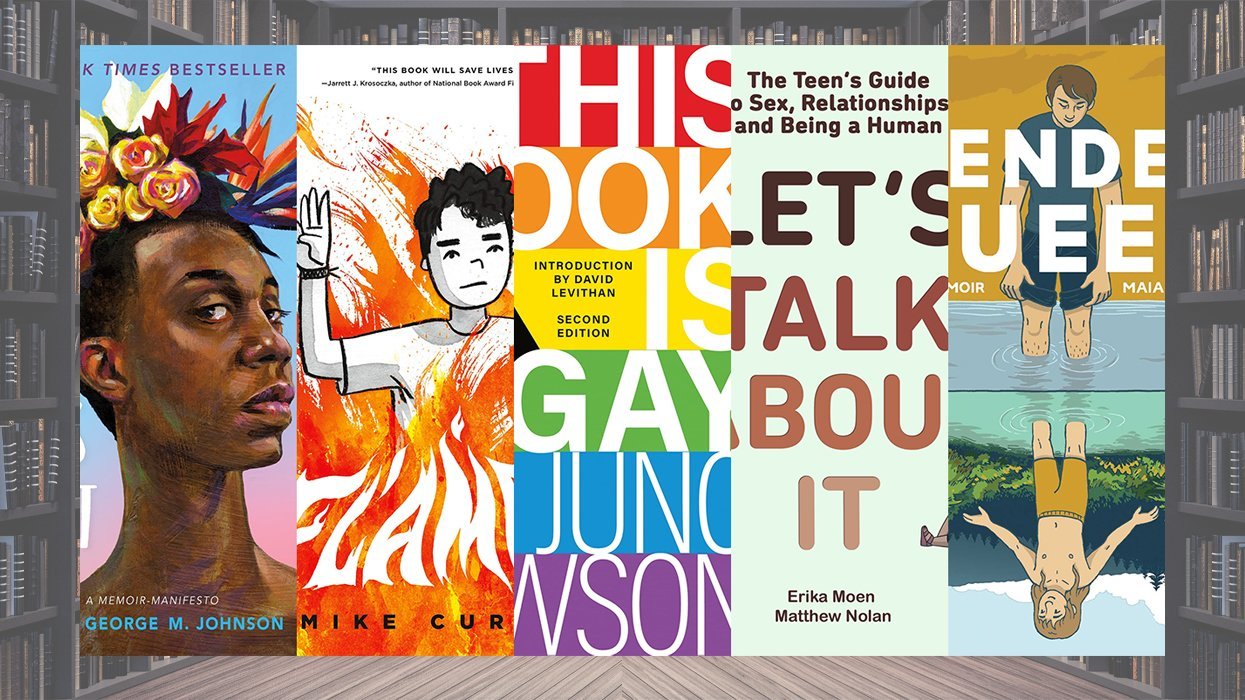

The 10 most challenged books of last year

April 13 2024 10:06 AM

Mary & George's Julianne Moore on Mary's sexual fluidity and queer relationship

April 13 2024 10:00 AM

Investigation launched after man screams homophobic slurs at queer couples on D.C. metro

April 13 2024 9:59 AM

Germany makes it easier to change gender and name on legal documents

April 12 2024 6:06 PM

A youth's call to action on this Day of NO Silence

April 12 2024 5:00 PM

Democrats introduce resolution in support of LGBTQ+ youth

April 12 2024 4:35 PM

Colton Underwood is hoping to create a gay reality TV dating show

April 12 2024 4:28 PM

Idaho closes legislative session with a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ laws

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Pride

Yahoo FeedElevating pet care with TrueBlue’s all-natural ingredients

April 12 2024 1:39 PM

Watch Jimmy Kimmel's hilarious LGBTQ+ campaign video: 'You can't spell Biden without Bi'

April 12 2024 12:00 PM

Pride

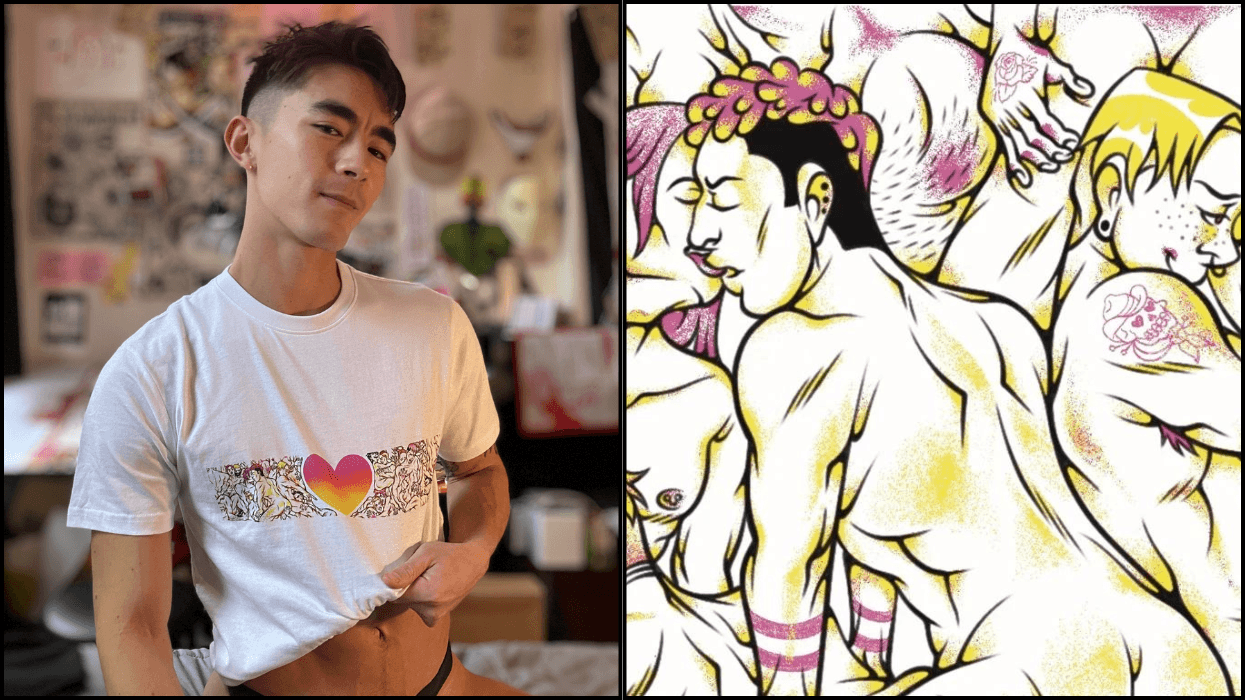

Yahoo FeedCreating erotic art and advocacy with adult entertainer Cody Silver (EXCLUSIVE)

April 12 2024 11:39 AM

How I navigated through religious trauma

April 12 2024 11:00 AM