At an hour and 50 minutes, The Jazz Age teeters just around that length of a play in need of some sort of intermission -- just when the "mad dash for the bathroom" pangs sweep over your body, the play comes to a screeching halt. And it's that sort of frantic energy that makes Allan Knee's high-pitched piece such a success (thanks, in large part, to director Michael Matthews's quick pacing and the in-your-face performances of a trio of able actors).

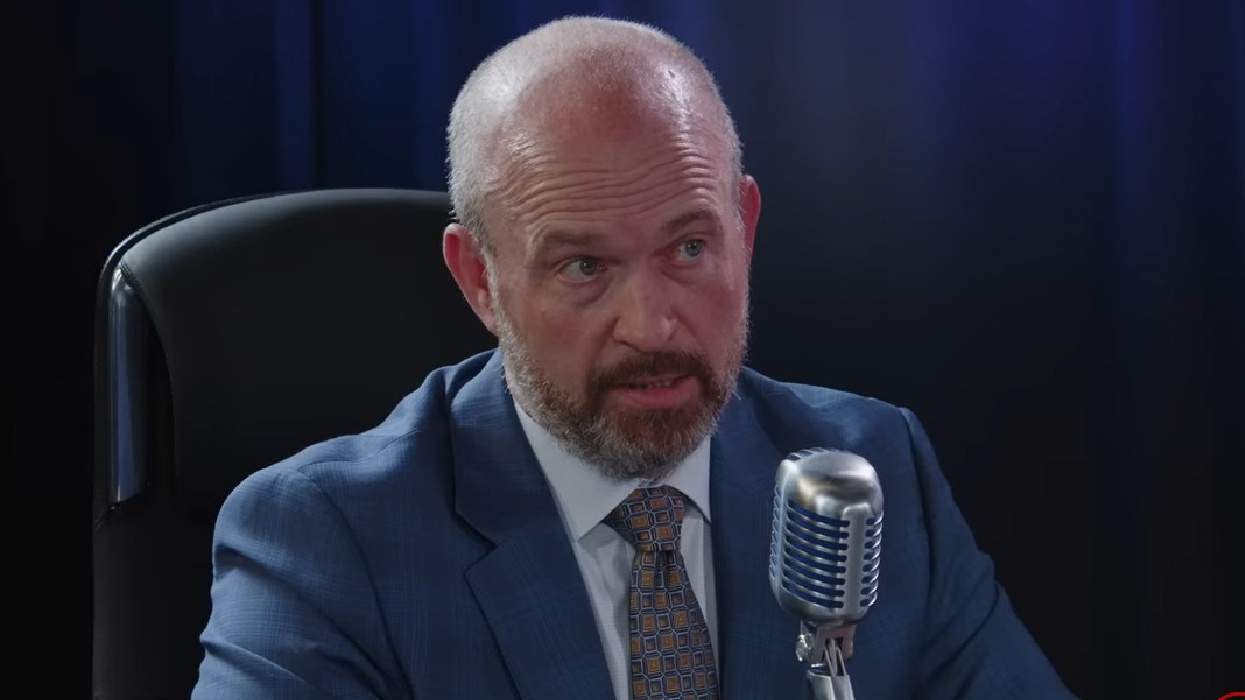

The story of authors Ernest Hemingway (Jeremy Gabriel) and F. Scott Fitzgerald (Luke MacFarlane of TV's Brothers & Sisters ) and their unusual, codependent -- and, at turns, bordering on sexual -- relationship takes the audience on a fast-paced ride through the highs and lows of the Jazz Age, a period from 1918 to 1929 when Fitzgerald's career flourished, then fell apart, and Hemingway clawed his way from relative obscurity to great American author.

The pair make for an odd couple -- Hemingway, masculine and secure; Fitzgerald, at times euphoric and childlike, but often crippled by a lifelong battle with alcoholism and an overwhelming need to top his life's great work, The Great Gatsby.

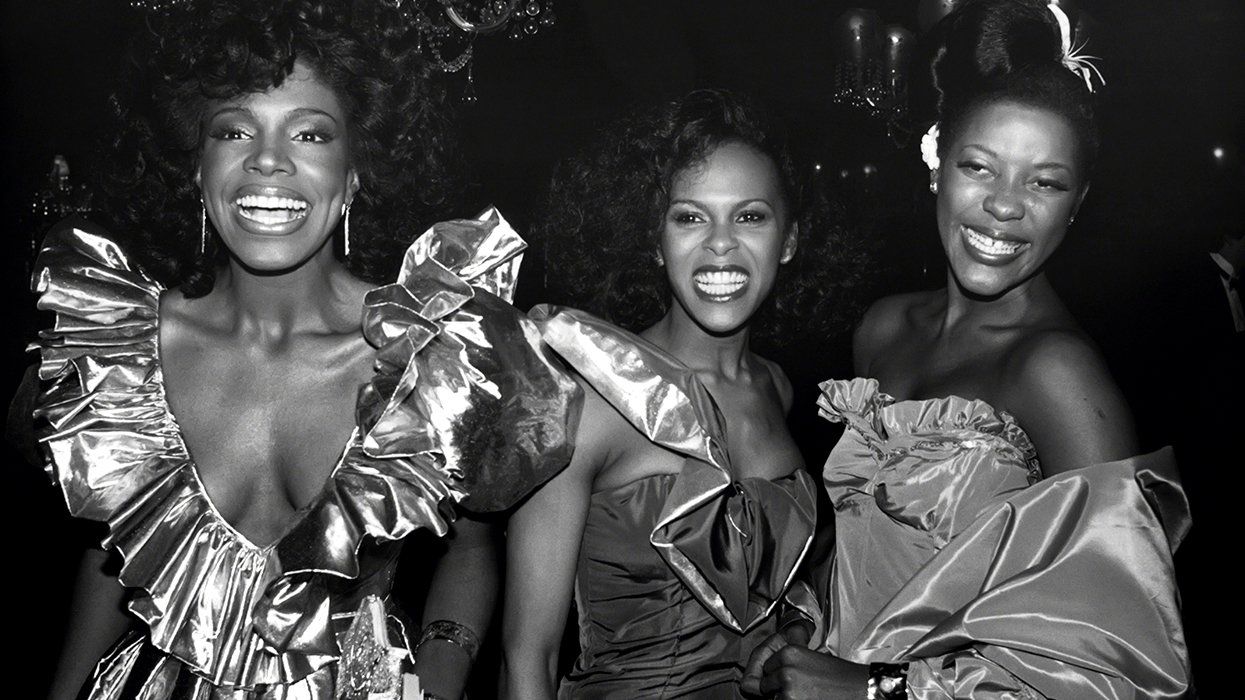

Along for the ride is their female foil, Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (Heather Prete) -- platinum blond, oozing sexuality -- the love of Scott's life, he says, though the two spend the bulk of the play building each other up just to rip it right back down again.

Scott's real fascination is with Hemingway. The two box, drink, talk literature -- they even compare dick sizes in one of the play's more heated moments. They can't be together, but they can't seem to stay apart for long. They are the real loves of each other's lives, though -- at least in The Jazz Age -- for the most part, it's strictly platonic.

Both Gabriel and MacFarlane are up to the challenge of running all systems go in a relatively small black box theater. The play requires that each actor roar above a three-person jazz band (the talented Ian Whitcomb and his Bungalow Boys, who play throughout the show) without going too far over the top. Their conversations are intense -- Gabriel the able man's man while MacFarlane channels the sort of feminine exuberance that fits him so well on Brothers & Sisters and manages to refine it for an intimate space.

The third wheel, Prete is faced with a difficult task -- make your trademark whiny, sexpot southern belle sympathetic. It takes her a while (mostly because her character is the least fleshed out of the three), but when Zelda's mind begins to unravel, Prete lets loose -- a scene in a mental hospital is particularly fine.

Sets are minimal, and that suits the play just fine. Save for the occasional almost bedroom tryst and a whole lot of drinking, The Jazz Age is really about these three actors. The play's abrupt ending is a bit of a jolt and takes a while to swallow, but as with the rest of the play, it goes down -- that it takes a bit of energy from the audience to let it all soak in seems oddly fittings ... as if Fitzgerald and Hemingway wouldn't have it any other way.