A huge percentage of transgender people (41 percent in the U.S.) attempt suicide, and suicidal thoughts dot the storyboards of many of our lives. We trans rights advocates talk often about how to end this epidemic, but nonetheless a certain shadowy silence prevails.

A cultural taboo about feeling the desire to die keeps many suicide survivors from ever discussing their experiences, much less doing so publicly. But I believe that for those of us who feel able and willing, telling the stories of our attempts can provide a segue into a conversation for healing -- for us survivors as well as the entire community.

Like many other trans people, I have attempted to end my own life. Until now, it's not something I've shared with anyone besides my girlfriend, who is also trans. Writing down the story of my attempt, I am immediately filled with feelings of shame. As if I was somehow weak for being consumed by the darkness of the hopelessness that filled my life at that time. But I've seen too many trans adults and youth -- including, recently, a friend -- taking their lives to remain quiet.

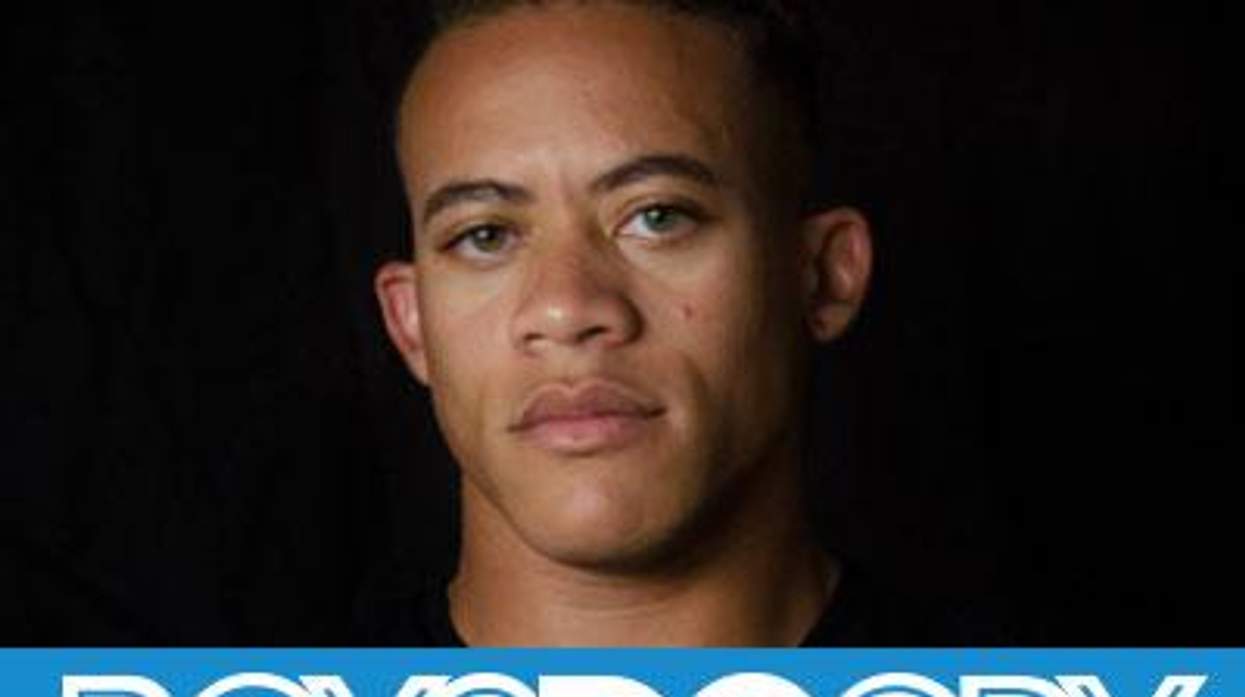

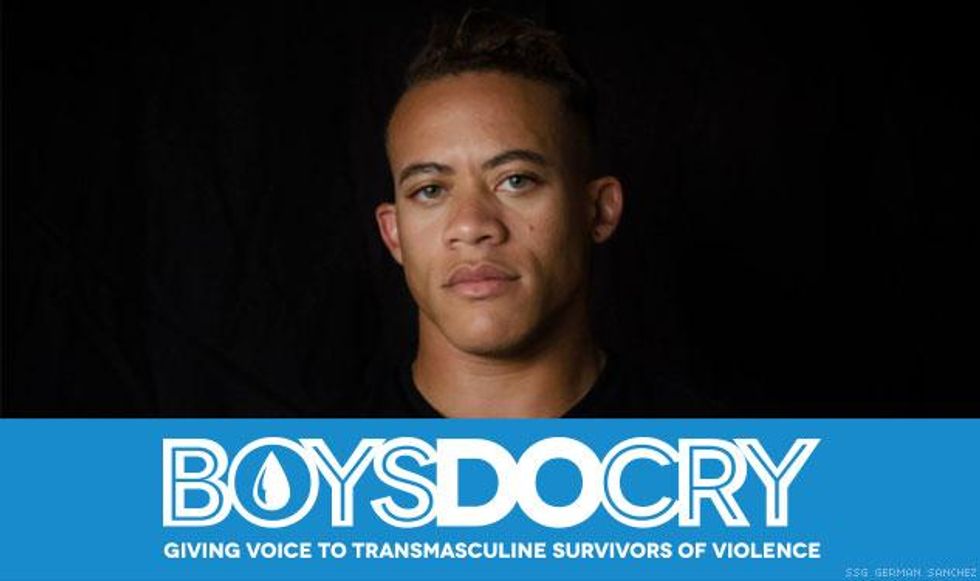

Although as an out trans military member I have gotten many kind words and cheers lately for being so resilient, it's important that people know that those who attempt suicide don't "look" a certain way -- this can happen to anyone.

So I'll share my story here, with a warning to readers that it may trigger feelings of trauma, so please read on to the next page if you feel able.

The afternoon I found myself fashioning a noose from an old bedsheet, I was 13 years old and home alone. I'd been feeling like there was no escape from my life at that point. I decided that hanging myself from the banister of the second-story stair railing in my house was the best option to end the pain. I trotted heavy-footed up the flight of our tan-carpeted stairs, working the sheet in my hands. The glow from a skylight above lit the top of the landing.

I knelt. I tied a slipknot from the free end of the sheet and reached out a hand to tightly grip the vertical slat of the open railing. I took a deep breath and looked up at the skylight once more. The entire house was so silent, but I felt calm. Then I sighed so loudly it startled me.

Another second passed, and I felt peaceful again. I was going to be free from all the emotional pain I had been suffering. I wouldn't have to fight anymore. I took a deep inhale, pushed myself up to stand on the bannister, locked my eyes on the window in the far wall, and jumped.

Instantly, I felt the painful, violent jut of the sheet against my throat. My eyes teared up and my hands instinctively jumped to the sheet wrapped around my neck. As I clawed at it to no avail, I became filled with terror.

I was still alive, and I was stuck.

I hung there 10 feet off the ground for what seemed like hours, slowly suffocating and violently twitching. But then the unexpected happened: The sheet tore. A loud ripping sound filled the air and then I fell to the ground, gasping and listless. My whole body was a ball of writhing aches as I lay for a few minutes, starting to feel, in the most primitive of ways, more alive than I ever had.

When I finally caught my breath, I made my way slowly to the kitchen and retrieved the scissors. Gasping, I cut the sheet from around my neck, then threw it in the outside trash can. The rest of the day was uneventful.

When my mother returned home that night, she didn't ask about the red ring around my neck. I went back to my life as being invisible and insignificant once more. My living situation, which had caused enough anguish to push me toward my desperate leap, carried on.

A year earlier, an older cousin had finally stopped raping me. Nearly 15 years later he was finally arrested for his history of violent crimes and given three life sentences in jail, including for the rape of an elderly woman. He had started sexually abusing me at age 4, and it had carried on for eight years. Meanwhile, my home life wasn't safe either.

My mother was dating a woman I'll refer to here as "Nancy." Nancy began to take care of me when my mother was deployed in the Navy. The day she became my main caregiver was the day I began facing the most debilitating years of abuse that still affect me today.

Nancy was a crack addict. She was heavily involved in drug sales and would oftentimes use me to deliver drugs to customers. As a young child I would walk alone to different places and drop them off and retrieve the money. Nancy would often get high and beat me in a strung-out rage. Afterwards she would lock me in a dark closet for days at a time, only opening the door to push in a small bowl of rice.

I can remember sitting in the closet, hugging my knees and listening to "Last Dance" playing loudly outside; to this day I still feel panic when I hear that song.

Eventually child protective services contacted my mother because a neighbor had called it in. She returned from her deployment immediately, but life with her would never be happy-go-lucky. I was oftentimes handed back and forth between relatives. I felt like a burden that my mother had to deal with. When she drank -- which was a lot -- she'd complain that I was holding her back in life. Sometimes my mom showed me this by putting her partner's kids before me.

One very sad time sticks out in my memory: when my beloved great grandmother, who I'd been sent to stay with often, passed away. Mom left me at home and took her then-girlfriend (a different woman than Nancy) and the girlfriend's child to the funeral instead. I was left at home with no money or access to food for over a week. She didn't call or even leave a note. To this day, I still have no idea where my great-grandmother is buried in Kentucky.

By age 15 I was surviving on the streets. My mother had given me yet another violent beating and then kicked me out. When she'd beaten me before, I'd ended up punished -- I received two separate six-month sentences in a juvenile correction center and the county jail -- so I didn't bother to seek help anymore. In Virginia, where we'd moved for her military work, the commonwealth's standard was to take the word of the guardian over that of the juvenile in domestic assault cases.

I moved in with friends, took on full-time hours at a Panera Bread, and finished high school all on my own. I joined the U.S. Marine Corps in my junior year and I made my life what it is now. I came from the literal bottom and created everything I have from my own striving. I remember my mother saying to my Marine Corps senior drill instructor how "proud" she was of what she "made me into." My instructor replied, "That Marine is only a product of [him]self, [he] made this happen." She was right.

Like so many people suffering violence and emotional pain, not once during this period did I share with anyone these tragic stories. I have always internalized my hurt and forced myself to drive forward every day after I tried to hang myself.

I now have an anxiety condition from combat post-traumatic stress disorder and also, more than likely, from my experiences of abuse as a child. I feel that I largely understand what it all has meant and have become more resilient. I have decided to accept the reality of how it was and try to move forward. For me -- though I know it's not for everyone -- part of that looks like speaking publicly and unashamedly about my past.

Suicide is a topic that needs to be discussed in the light of day, maybe even while sitting at the table with friends over coffee. It shouldn't be hushed. Let's start more conversations, even if they scare us.

When we do this, we need to move the conversation away from hypermasculinity and understandings given to us by our patriarchal, cisnormative society. Suicide is very real for veterans -- many of whom are wrongly taught to be ashamed because it is "weakness," and weakness is coded as "feminine" in our patriarchy -- and it is very real for transgender and gender-nonconforming people.

Before one more person falls into the abyss, let's talk openly and honestly about the topic. If you've had an experience with a suicide attempt and feel emotionally able, you can consider telling your story like me. We as a nation need to start the healing by showing and supporting our own humanity.

Sgt. SHANE ORTEGA currently serves as a U.S. Army helicopter crew chief in Oahu, Hawaii. He is considered the first openly transgender soldier in the U.S. military. He can be reached at @OnlyShaneOrtega.

If you are a trans or gender-nonconforming person considering suicide, Trans Lifeline can be reached at (877) 565-8860. LGBT youth (age 24 and younger) can reach the Trevor Project Lifeline at (866) 488-7386. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255 can also be reached 24 hours a day by people of all ages and identities.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.