Sgt. Shane Ortega wakes up and shuts off his alarm clock at the same time every workday morning. The right time.

He showers, stops in front of the mirror, carefully scrapes away the faintest hint of stubble from his cheeks. He moves to his bedroom, donning his crisp office clothes just so. He's out the door, right on time, headed to the Oahu military office where he's been doing human resources work ever since he was grounded -- temporarily, he intends -- from flight last summer.

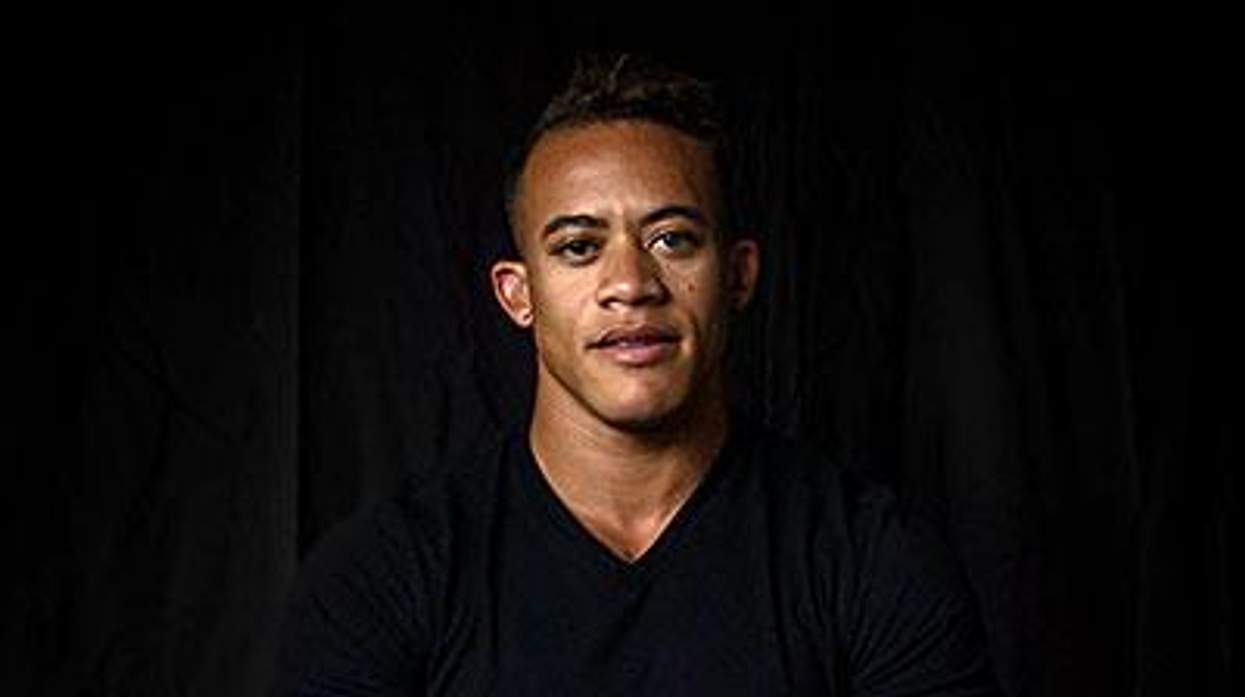

Sgt. Ortega is never late. He is never rumpled. He never has an "off" day. And he makes sure of it, because he's one of the first openly transgender people in the U.S. military, and he knows the world is scrutinizing him.

"Honestly, I have to be perfect right now," the 28-year-old Army helicopter crew chief tells The Advocate over the phone from Wheeler Army Air Field. He follows his words with a light laugh that will be repeated many times over the next 40 minutes, one that seems to dissolve clouds of self-pity before they can gather. "Like, I couldn't get a speeding ticket. I can't be late. I can't forget to shave one day of the week. I have to be absolutely perfect."

And then, instead of resting, Ortega spends most of his lunch break talking about living a life that has become more than his own.

"I don't think anyone really understands the level of perfection that I have to have right now that I stepped forward," he admits. "But I understood the weight of the matter. It was part of what I juggled in my judgment before I decided to do that. And it's really uncomfortable, to be honest. But if I don't do it, it doesn't help anyone else."

He's referring to people like the field grade officer who, he shares, privately sought him out after over a decade of service to tell him that they were transgender and had not felt able to come out. "It's like, what can I do?" Ortega wonders aloud. "I can stick my neck out further."

Last month Ortega stuck his neck out when he stepped into the national spotlight in a Washington Post article on the U.S. military's continued policy against service by transgender people, becoming the institution's most publicly visible active-duty trans soldier.

It was a decision he tells The Advocate he weighed carefully, though not necessarily because it would jeopardize his status with the military. Ortega had already more quietly let the U.S. Army know, through the American Civil Liberties Union in September, that he would not passively accept being "separated" -- released from active duty -- for being transgender, if his unexpected grounding ultimately led there.

Rather, Ortega deliberated on whether to go public because he knew it could have implications, large and small, for every other transgender person serving in the U.S. military. And while many can only imagine that his visibility will bring positive effects, behind the scenes the issues become much more complex and individual.

Then, those issues are compounded by the institutional military regulation that bars transgender people from serving openly: Department of Defense Instruction. It proclaims that any type of gender-confirming clinical, medical, or surgical treatment is evidence of "disqualifying physical and mental conditions." Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter, who took office in February, has said he is "open-minded" about reviewing the policy, which has not been updated since it was written in the 1970s. But despite pressure from activists within the ranks and in Washington, the Pentagon has confirmed that no specific review of the transgender-specific ban is currently under way.

"However, the Department of Defense began a routine, periodic review of the Department's medical accession policy, DoDI 6130.03 in February 2015," a Pentagon spokesman, Cmdr. Nate Christiansen, tells The Advocate via email. "The review will cover 26 systems of the human body (e.g., neurologic, vision, learning, psychological and behavioral). We routinely review our policies to make sure they are accurate, up-to-date and reflect any necessary changes since the Department's last policy review. ... The current periodic review is expected to take between 12-18 months; it is not a specific review of the Department's transgender policy."

Given the long history of the military's ban on open service by transgender Americans, one naturally wonders why Ortega's status with the Army has been placed in limbo now, following a medical test showing "elevated" testosterone levels for a "female" soldier. Knowing that military health care providers could have performed that same test, and arrived at the same conclusion, any time over the past four years Ortega has been undergoing hormone therapy only allows one to begin to grasp the intricate balance of Ortega's journey.

Metaphorically, Ortega represents every trans soldier who has ever served -- a number totalling 15,500 currently on active duty, according to a recent estimate by the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law. But he is not every soldier. He is Sgt. Shane Ortega, a man whose exact path will never again be traced by another recruit. And he knows why, at least in part.

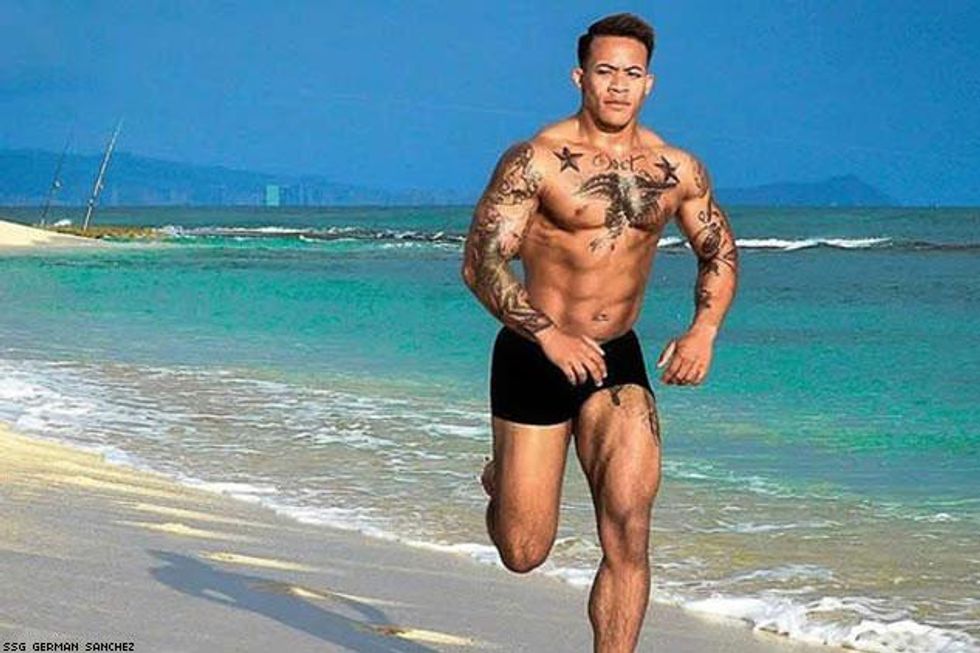

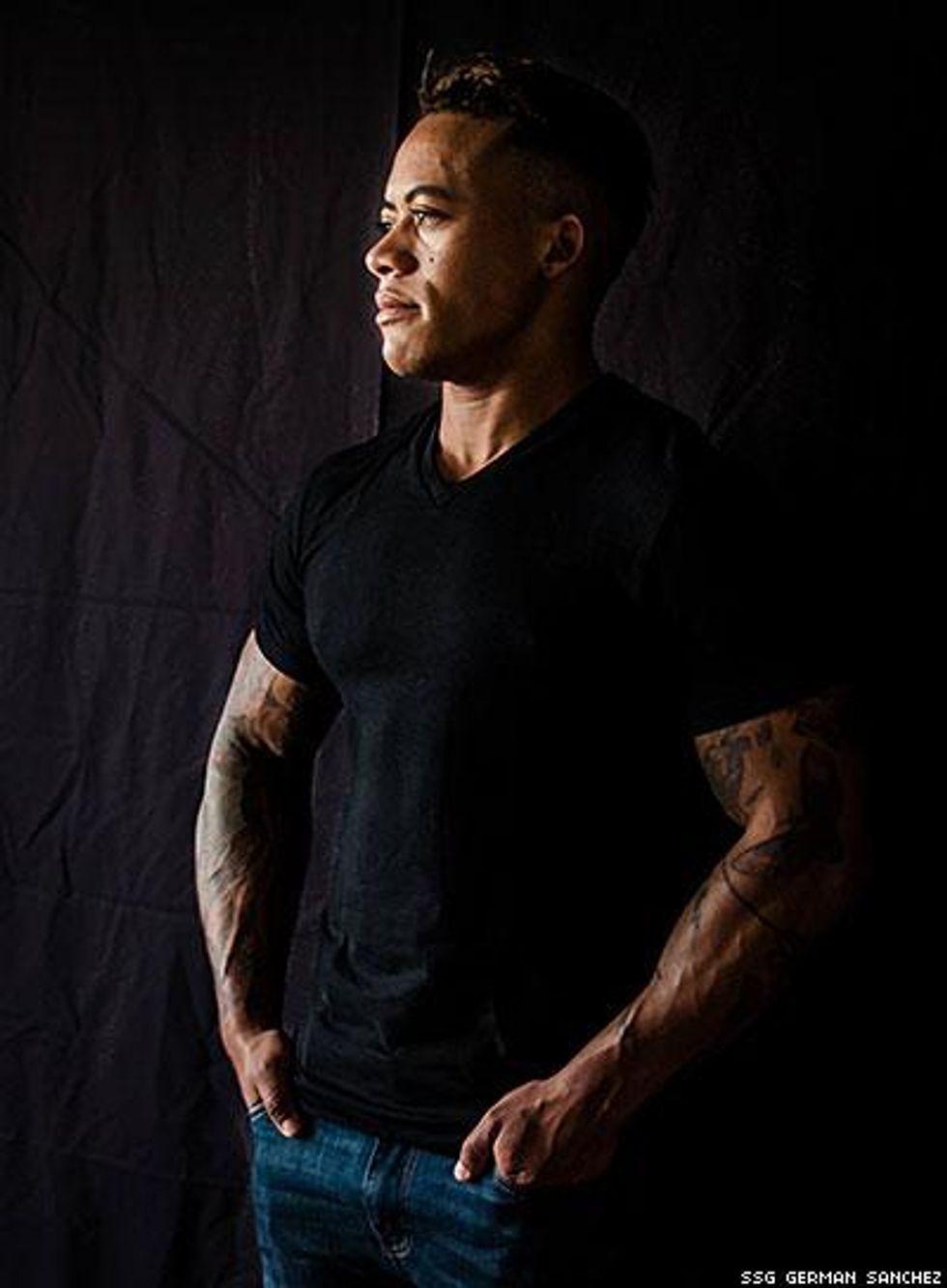

He phrases mildly what the public has immediately latched on to: Ortega is not just Army fit. He is all bulging pecs and biceps, hard abs, and sculpted torso and quadriceps -- a man who's gone above and beyond that old Army motto of "be all that you can be."

Yet rather than draw attention to the unfathomable amount of work he's put into honing his body, Ortega seems simply grateful that he was born disciplined enough to keep to an intense diet and workout schedule. He recognizes it as a gift that has allowed him to help other trans soldiers coming up behind him, and possibly what has enabled him to be out as trans in the military for so long.

Ortega, as it turns out, started intuitively striving for perfection among his military peers long before he hit the national spotlight -- even before he knew exactly why he was doing it.

"Inadvertently, I was trying to set a precedent with my service," he says, thinking back on his exemplary decade serving in the Marines and Army. "The reason why I train so hard, why I try to have high fitness standards even among men, is so that [the U.S. military] can't be like, 'Transgender men can't achieve this standard' or 'They should be barred from Special Forces.' ... I can start a precedent of saying, 'OK, they can meet the standard, stabilize their testosterone, they're competent, they're hard workers.'"

But, of course, Ortega would never have reached a place where he could set such precedents if his supervisors had long ago benched him when they learned he was transgender. And here is where his incomparable fitness and his honesty with his chain of command -- two factors Ortega groups under a favorite word, "integrity" -- seem to have played a key role.

Had Ortega's performance faltered at any time, it may have been grounds for his commanders to follow military guidelines that instruct -- but do not require -- decision-makers to see being trans as evidence of "mental disorder." But because he has met and exceeded standards, Ortega may possibly have been spared. And now, partly in response to the ACLU's September motion, the decision of whether to separate trans soldiers like him has been taken out of the hands of his company commander and been placed with Assistant Secretary of the Army for manpower and reserve affairs Debra S. Wada, the highest-ranking civilian in Army Command.

Discussing this on the other end of the phone line, Ortega patiently turns to the questions that still hang in the air: Why didn't his then-company commander simply follow the guidance on separating trans soldiers four years ago when he began testosterone therapy? And why has the issue come up now? He moves to a quieter spot in his office and audibly settles in for a long explanation.

The short version: In 2011, six years after Ortega initially entered the Marine Corps as a high school junior, he visited a civilian doctor to discuss the fact that he was transgender and was ready to begin his medical transition. He was seeking access to testosterone, which the American Medical Association considers "medically necessary" treatment for transgender men undergoing physical transition. Once he obtained the hormone prescription, he followed his duty as a soldier to report the civilian doctor's findings with Army medical personnel and his chain of command. "By me making sure I reported [my new medication], I was protected in that regard," he explains. "But under the military regulations about having gender dysphoria, I was absolutely not protected. I could have totally been separated -- but I wasn't."

The short version: In 2011, six years after Ortega initially entered the Marine Corps as a high school junior, he visited a civilian doctor to discuss the fact that he was transgender and was ready to begin his medical transition. He was seeking access to testosterone, which the American Medical Association considers "medically necessary" treatment for transgender men undergoing physical transition. Once he obtained the hormone prescription, he followed his duty as a soldier to report the civilian doctor's findings with Army medical personnel and his chain of command. "By me making sure I reported [my new medication], I was protected in that regard," he explains. "But under the military regulations about having gender dysphoria, I was absolutely not protected. I could have totally been separated -- but I wasn't."Why the lucky break? Ortega speculates that perhaps, "part of that too was just because I was such a high performer," but there's no way to ever know for sure. "It's kind of subjective," Ortega adds. "It depends on the chain of command."

For the next four years, Ortega underwent testosterone therapy while serving in the Army, including a tour in Afghanistan, without a hitch. He never strove to hide his lowering voice or stubble, and never asked until right before the release of the April 9 Washington Post profile to be called "Shane" or "he."

"But," he reveals, "that was already happening in my command. People are going to begin realizing that you look really male. 'That's a dude,' you know?" Hearteningly -- especially for the potential future of out trans service members -- Ortega says his gender identity never became an issue among peers or military leadership.

Never, that is, until Ortega's most recent flight physical reached Fort Rucker, Ala., home of the Aeromedical Board.

Fort Rucker officials are the ones who ultimately decide which troops do and do not fly in the U.S. Army, even if the soldier has already gone on a number of flights. The board's decision did not accord with that of Ortega's chain of command.

"When they finally reviewed my flight records, they were like, 'This is a female with testosterone in their system,'" Ortega recalls. "On the flip side, in the civilian world, according to the [Federal Aviation Administration], transgender people are allowed to fly. So it's hilarious," he concludes, letting an unusual edge seep into his even voice. It subsides just as quickly. Perhaps there's a part of him that knew he was working on borrowed time ever since he first held that testosterone prescription back in 2011.

Today, Ortega finds himself in desk-duty purgatory, with no indication of when he can resume leading helicopter crews. His chain of command has now asked the U.S. Army point-blank what to do with him, placing subtle pressure on the trans military ban that has slowly been crumbling since the 2011 repeal of the "don't ask, don't tell" policy barring open service by lesbian, gay, or bisexual soldiers.

Today, Ortega finds himself in desk-duty purgatory, with no indication of when he can resume leading helicopter crews. His chain of command has now asked the U.S. Army point-blank what to do with him, placing subtle pressure on the trans military ban that has slowly been crumbling since the 2011 repeal of the "don't ask, don't tell" policy barring open service by lesbian, gay, or bisexual soldiers.In return, the Army has offered mostly silence. "Essentially what the Army is saying is, 'OK, Sgt. Ortega, we're basically going to put you on the back burner for a while until we decide some sort of answer," Ortega says. It's now been over half a year.

Despite the military's foot-dragging, an answer to the question of whether transgender people are fit to serve has already been provided -- not only by the 18 countries that currently allow trans citizens to serve openly, but by several prominent studies. These reports have determined that there is "no compelling medical reason" to continue to deny open military service to transgender Americans, as a March 2014 study backed by a former U.S. surgeon general and performed by the Palm Center concluded. Also, a nine-member commission, including several retired generals and flag officers, concluded a three-month study last August with the recommendation that changing the current regulations to allow trans citizens to serve openly would be "neither excessively complex or burdensome."

The Palm Center, which conducted two of those long-term studies, had a definitive answer to the question Defense Secretary Carter posed in February when he expressed his "open-minded" position on reviewing the longstanding ban. "In response to a question today about whether transgender troops can serve in austere environments, Secretary Carter asked, 'are they going to be excellent service members?'" the independent San Francisco-based think tank wrote in February. "The answer to this question, based on the experiences of 15,500 transgender troops who are already serving, as well as academic research, is an unqualified yes."

Meanwhile, Ortega remains optimistic that his downtime might not be a total loss: He sees hope that the Army may be learning about transition-related medicine from his case in a way it hasn't before. He explains that though the Army has specialists who understand endocrinology for transgender children, "there's no one who specializes in ... adult hormones," making his lab reports "uncharted territory" that Army health care providers can begin gathering "baseline data" from.

And he remains confident that he's ready to resume service as soon as he's given the green light: He's already passed his flight physical twice, and his chain of command awaits his return. He has even been cleared of ever having had gender dysphoria (distress over incongruity between one's gender identity and the sex one was assigned at birth) by his brigade's senior behavioral health officer. It's an unusual finding for a trans patient that may too prove to be a useful baseline.

"According to the military and my doctor, I've never had gender dysphoria," Ortega explains. And he concurs with their findings. "I don't have it. I'm comfortable with who I am," he asserts, though he says he understands the nuances of the loaded term. Raised by a lesbian mother who served in the military during the "don't ask, don't tell" era, Ortega says he was exposed to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders -- the book that officially defines "gender dysphoria," and at one time similarly defined homosexuality as a mental illness -- from childhood.

While the term "gender dysphoric" is often bandied about colloquially as a synonym for "transgender," Ortega -- and, importantly, his military health care providers -- appear to view the condition more as a temporary, or even avoidable, one.

"For me, I think gender dysphoria is kind of like before people come out as gay or lesbian," he explains, his voice thoughtful. "That time period where you're trying to figure out who you are. Once you acknowledge and actually know who you are, I don't think you really suffer from dysphoria. I think you just need treatment at that time. It's like saying, 'I'm hungry.' Until you get something to eat, you're still hungry, you know? ... You always know, 'I'm hungry, I should eat a sandwich.' So eventually, you're like, 'All right, cool, I got a sandwich.'"

The distress, Ortega adds, doesn't emerge inherently from being trans but comes from the social rejection that can sometimes accompany the identity, potentially layering anguish on top of that temporary hunger for gender congruity.

Yet despite his own lack of dysphoria, as well as his seemingly charmed four years of reprieve that set the stage for his unparalleled outness, Ortega says he constantly cautions other trans soldiers to not expect the same outcome if they come out to their own chain of command.

"I've had hundreds of emails, to be honest, from active-duty service members as well as some reserve service members," he shares. "I get people who say like, 'How can I serve [openly as a trans person] like you?' and I always have to explain to them, 'There's no protections or guarantees for you. You can take these steps forward, but you could be liable for separation.' It's really depressing."

"Stories like Shane's are more common than you think, and the pressure these service members feel is understandable," says Allyson Robinson, herself a transgender Army veteran who currently serves as the director of policy for LGBT service member organization SPARTA. "The five transgender service members we took to the Pentagon last January to share their stories with senior leaders felt that pressure, as do the other transgender SPARTA members whose commands have chosen to retain them despite the regulations. But it's infinitely preferable to the pressure thousands of other, less fortunate transgender service members feel: that of having to hide their true selves just to keep their jobs and keep serving."

Then he shakes off any traces of despondency. His voice brightens and he laughs. There's simply too much that needs to be done to dwell, and he knows if he doesn't make the most of his time on the national stage now, the chance may never come again.

"If the public doesn't get to see this [trans] person actively serving, actively doing this job, and proving them all wrong, then they'll never believe it can be done," he says. "That's why I keep doing this. I have a few more years left in my contract. I figure I can keep pushing."

"To win open service for transgender Americans, we need to put faces to the fight," Robinson concludes. "I'm profoundly grateful that service members like Jacob Eleazer, Rae Nelson, and Shane Ortega have stepped forward to serve in this way. It's making a difference in our work at the Pentagon and in the public square as well.'

So tomorrow morning, Sgt. Shane Ortega will inevitably rise. He'll shower, shave, and make sure no hair is out of place. He'll eat a measured amount of protein and later exercise with all his heart. He'll head to the office, carefully observing the speed limit, and arrive right on time. And then he'll walk to a desk and file other soldiers' paperwork all day. At night he'll dream of flying.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.