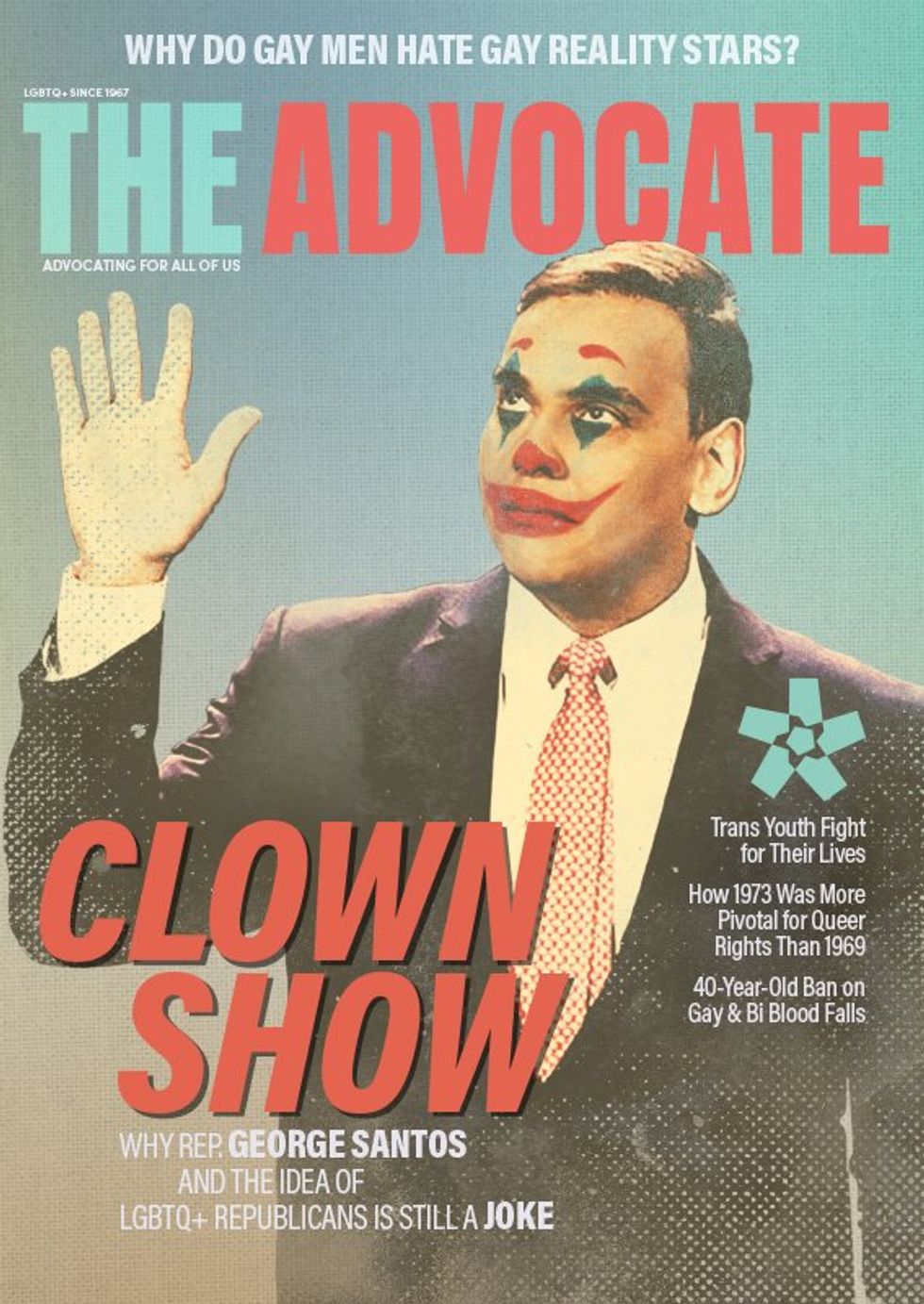

Please enjoy the March/April cover story of The Advocate and consider subscribing and supporting LGBTQ+ journalism.

In the spring of 1987, Republican Congressman Stewart McKinney died of HIV-related complications. Though his family denied it, McKinney was long rumored to be gay or bisexual.

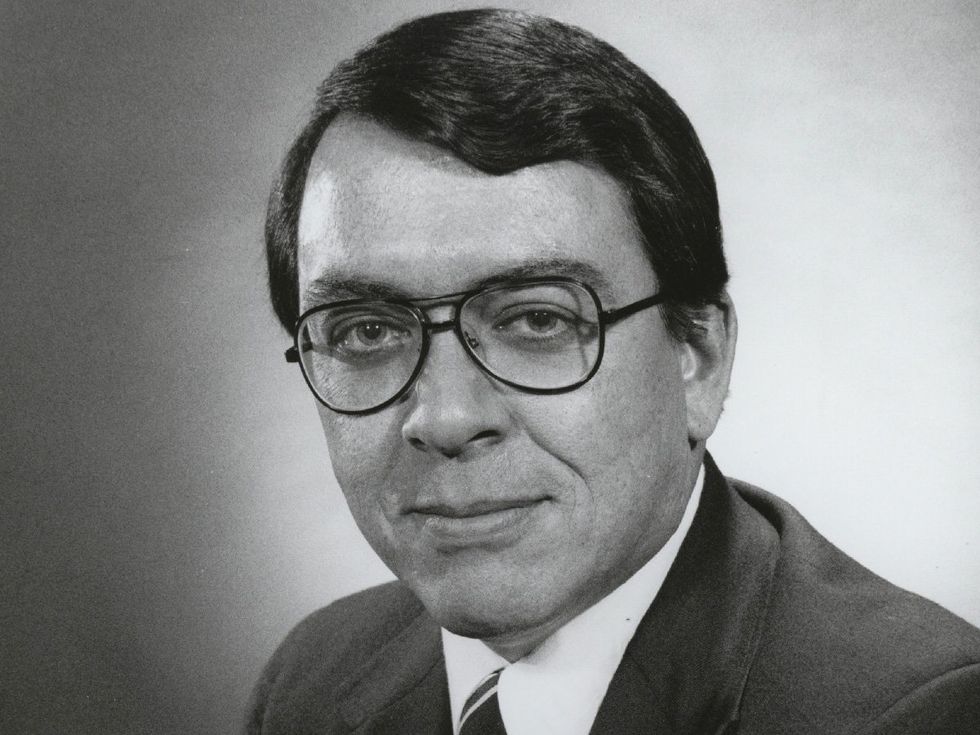

Prior to McKinney, the first two out — and not by choice — gay members of Congress were Republicans, and both left under a swirl of controversy and criminal activity. In October of 1980, while running for reelection, Maryland Congressman Robert Bauman was arrested and charged with soliciting sex from a 16-year-old male sex worker. He lost his reelection bid. The following year, Mississippi Republican Congressman Jon Hinson was arrested at a bathroom stall in a D.C. federal building, along with a male Library of Congress employee, on an oral sodomy charge; Hinson was forced to resign. Bauman, Hinson, and to a lesser extent, McKinney have essentially been erased from the meager history of LGBTQ+ Republican politicians.

Forty years after these three men served in Congress, things haven’t changed much in terms of LGBTQ+ Republican officeholders, particularly at the federal level. There is one Republican member of Congress, who, coincidentally, is lying about himself, has a sexual harassment complaint against him, and is under federal criminal investigation. The only difference is that George Santos was first elected as an out gay man.

To understand why there has not been more of an effort to field LGBTQ+ candidates and why the party still hasn’t made headway with queer voters, it’s important to note that the GOP made anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric and policies an unofficial (and later official) cornerstone of its platform for four decades. That means that overwhelmingly, LGBTQ+ voters consider the Democratic Party an ally — or, at least, less of an enemy than the GOP. According to a GLAAD poll conducted after the 2020 presidential election, 81 percent of LGBTQ+ voters went with Joe Biden.

The negative feelings LGBTQ+ voters have about Republicans stretch back decades.

Only one month before McKinney’s death, President Ronald Reagan, the standard-bearer of the party at the time, gave his first speech about AIDS at a luncheon for members of the College of Physicians. Reagan had been silent about the disease since it started to rage in 1982. Because it overwhelmingly affected gay men, Reagan, who had gay friends in Hollywood, stayed away from mentioning AIDS and its sufferers.

James Kirchick, the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, says the intersection of gay identity and AIDS for Republicans likely started within the Beltway, when Republican operative Terry Dolan, the founder and chairman of the National Conservative Political Action Committee, died of HIV-related complications in December of 1986.

In his book, Kirchick writes, “NCPAC exerted its influence primarily through the medium of the 15- and 30-second television attack ad, which Dolan pioneered and made into a staple of American political campaigns. ‘A group like ours,’ Dolan once bragged, ‘could lie through its teeth, and the candidate it helps stays clean.’”

Dolan lied through his teeth for years about his sexuality, all the while pushing conservative “values” and hyping his Christianity. “Of all the many gay men working in the Reagan administration and conservative movement during the 1980s, none more vividly exposed the punishing contradictions of their precarious existence than Terry Dolan,” Kirchick writes. “By day, he attended Catholic mass and delivered speeches containing assertions like, ‘I can think of virtually nothing that I do not endorse on the agenda of the Christian right.’ By night, he frequented the Eagle and cruised the steam room at a Capitol Hill gym.”

But Dolan’s short and secret life put the Republican Party in a bind. “At the Catholic monastery where Dolan’s evening memorial service was held a few days after his burial, the controversy over his alleged AIDS diagnosis presented the hundreds of friends and political allies in attendance with an uncomfortable realization: Here was the conservative movement’s most effective strategist reportedly struck down by a plague many of them considered divine punishment for an immoral lifestyle,” Kirchick notes.

Before the deaths of McKinney and Dolan, both parties were relatively quiet about homosexuality. The Democrats had Gerry Studds from Massachusetts, who was forced to come out due to his involvement in the 1983 House page scandal investigation. He was subsequently censured by the House after admitting a consensual relationship with a 17-year-old male. Fellow Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank came out in May 1987, prompted in part by McKinney’s death. Frank told The Washington Post that after McKinney died, there was “an unfortunate debate about, ‘Was he or wasn’t he? Didn’t he or did he?’ I said to myself, I don’t want that to happen to me.”

However, Frank also had a scandal that forced him to publicly address his sexuality. In 1985, he hired a male sex worker, who eventually moved in with Frank and became an aide of sorts. Frank had hired him, with his own money, to clean his house, be his driver, and run errands. The news of the relationship broke in 1989.

Both Studds and Frank went on to be reelected numerous times and retired on their own terms. Prior to the scandal-filled ’80s, there was hardly a blip on the radar as far as LGBTQ+ candidates and issues were concerned.

“There were some rumblings around 1974 and 1975 when New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug introduced the Equality Act, which was the first federal gay rights legislation. But in the early years of AIDS, the stark differences between the two parties’ attitudes towards the disease and gay men began to appear, as Democrats had positions on sex education, funding, and treating the disease which were opposed by Republicans,” Kirchick offers.

Fred Karger was a Republican political consultant who began his career in the 1970s and worked on several high-profile Republican campaigns throughout his career, including for Ronald Reagan; Reagan’s close friend U.S. Senator Paul Laxalt of Nevada; Texas Governor John Connally, who changed parties, becoming a Republican in 1973; and U.S. Senator Bob Dole of Kansas.

As a gay Republican, he took big steps in order to avoid being perceived as gay. “There were rumors, I’m sure,” Karger says. “But I did a pretty good job of hiding, especially back then; I had no choice. If I wanted a successful career, I had to stay in the closet. During this time, I had a relatively healthy relationship that began in 1979 and lasted about 10 years, and I went to some gay parties. But I was petrified that my secret would come out. During this time, there were several Republican and Democratic consultants who were gay, but you risked your career if you came out. It’s a real tragedy that we couldn’t be our true selves. Three decades later, I’m still pissed about that.”

Karger says he was fortunate for one thing, and that was working for legendary Republican strategist Bill Roberts. “He managed Ronald Reagan’s entry into politics in 1966 and worked for Arizona Republican Senator Barry Goldwater,” Karger recalls. “Roberts was a moderate guy, and if there were any candidates who were too extreme, we could veto them.”

One thing that Roberts and Karger agreed on was that California’s Proposition 6 had to be defeated in 1978. “We really were instrumental in getting Reagan to oppose California Prop. 6, which was known as the Briggs Initiative, that basically said if you were a school employee or a teacher, you could be fired for being gay,” Karger says.

Karger and Roberts convinced political consultant Peter Hannaford to ask his close friend Reagan to oppose the ballot measure. “It really turned into an aggressive campaign, and we were elated when Reagan agreed it was wrong,” Karger notes. “He wrote a letter in opposition and an op-ed against the [proposition] in the Los Angeles Examiner. He was instrumental in the [initiative] being defeated. That was a big deal, because remember, Reagan was preparing to run for the presidency, so supporting the gay community was risky. And at the time, we hoped that he would be an ally moving forward.”

“Reagan had a lot of gay friends, and Nancy? She had a million, which is why it’s so infuriating that he ignored our community and AIDS for so long. He really disappointed us and let us down,” Karger says.

The Log Cabin Republicans, an organization of LGBTQ+ conservatives, had formed in 1977. “Back then, the organization had clear goals, and primarily one of those was to fight against the Briggs Initiative,” Karger remembers. "For a while, they tried to do some work in raising awareness in the Republican Party about HIV and AIDS. But the difference between the Democrats’ response and the Republicans’ was night and day. The Republican Party just wouldn’t budge on AIDS, mainly because they didn’t want to be perceived as helping the gay community. They were beholden to the Christian right, who passionately preached that homosexuality was a sin.”

In 1990, there was a bit of comity between the two parties when Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act to provide grants to improve care for those affected by HIV. The bill was named after a teenage Indiana boy who contracted HIV through a blood transfusion and died of AIDS complications in April of 1990. The legislation passed 95-4 in the Senate and by voice vote in the House; it was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. Having the bill named for White, who became a national figure, gave cover for Republicans to support a bill for AIDS funding that on the surface made no mention of gay men.

Despite signing the Ryan White bill, Bush had a poor record on LGBTQ+ issues and AIDS. Frank, by then retired from Congress, told the Washington Blade in a 2018 interview that he asked Bush to rescind the rule put in place under President Eisenhower that said gay and lesbian federal employees could not get security clearances. “He refused to do it. Bill Clinton did a few years later,” Frank said shortly after Bush’s death.

And when the Blade asked Larry Kramer about Bush’s record on HIV and AIDS, Kramer said succinctly, “I will not give him credit for anything. He hated us.”

When Bush ran for reelection in 1992, he faced a galvanized Christian right led by former Nixon speechwriter and political pundit Pat Buchanan, who challenged Bush in the Republican primary race. Buchanan made gay rights his target and gave a vicious speech about “homosexuals” at the 1992 Republican National Convention in Houston.

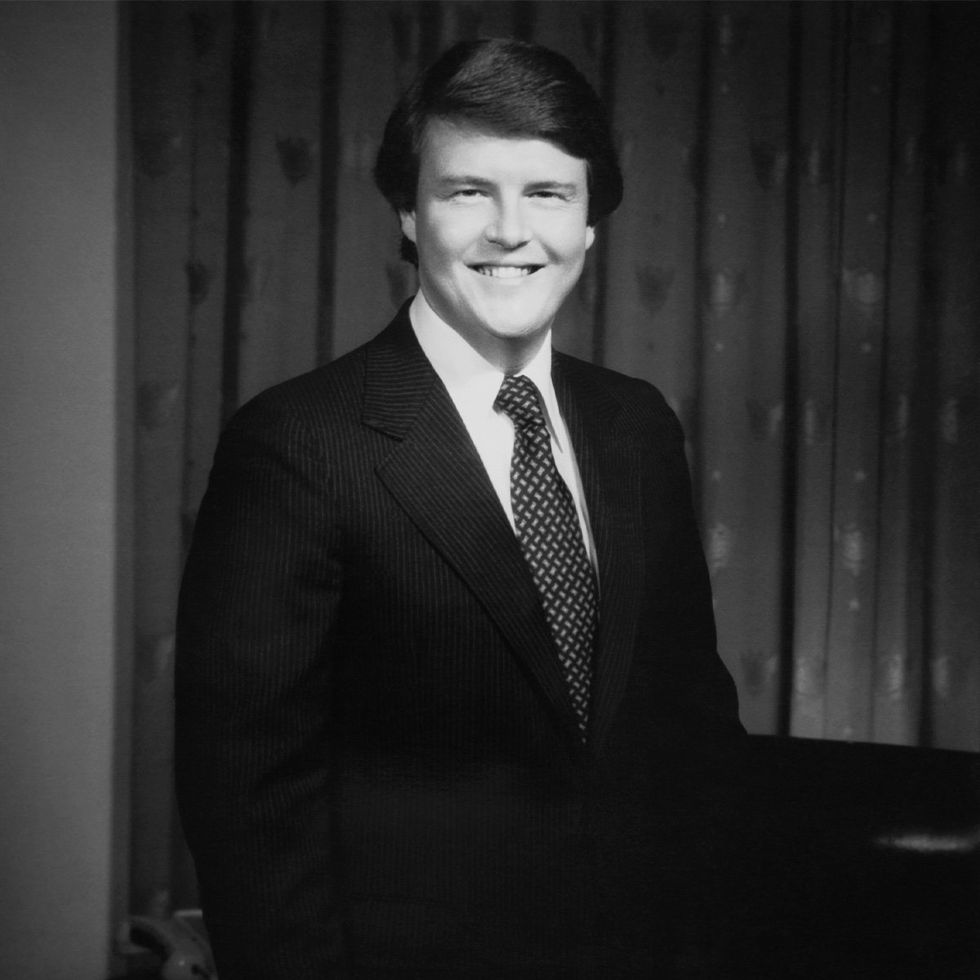

It was during Clinton’s first term as president that a gay Republican, one without any scandals, surfaced. In March of 1994, California Republican Congressman Robert Dornan outed a colleague, fellow Republican Steve Gunderson of Wisconsin, during a debate on the House floor about an antigay education initative. Gunderson came out and became the first out gay Republican elected to Congress when he won his reelection bid that same year. He did not seek reelection in 1996.

When Gunderson came out, he felt accepted within the Republican Party. “Honestly, I was,” he says. “But it was the classic case of first, get to know a person who is gay and then your feelings will change. Because my Republican colleagues knew and respected me both as a person and as a legislator, the fact that I was gay just didn’t matter. More than one colleague would come up to me and say things like ‘My nephew is gay’ or ‘My sister is a lesbian.’”

Two years later, Jim Kolbe, a Republican representative from Arizona, came out after he voted for the Defense of Marriage Act, which angered a lot of activists, who threatened to out him. Kolbe served openly, was reelected five times, and opted not to run again in 2006. He died last year.

Since Gunderson and Kolbe came out, several Republican congressmen have come out as gay or bisexual after they left office — Michael Huffington of California and Aaron Schock of Illinois are just some examples. And then there was Florida’s Mark Foley, who was caught sending lurid texts to a page in a 2006 repeat of the 1980s scandal.

In the 2012 election cycle, Karger became the first out gay major-party presidential candidate, eight years before Democrat and current Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg ran. Karger switched sides and supported Buttigieg in 2020. “Even 13 years ago, being a gay Republican was shocking. I remember dropping the gay bomb during a campaign speech in Manchester, N.H., and how all the Republicans in the crowd had frozen expressions,” Karger recalls. “I never ran away from it, and I eventually dropped out, but I can tell you I would get tons of emails and messages from Republican voters telling me their son or brother was gay.”

And here we are today. Since Kolbe’s retirement, the Democrats have elected 17 LGBTQ+ representatives and senators to Congress. And the Republicans? One: George Santos.

Why Republicans haven’t fielded more LGBTQ+ candidates reflects the party’s inability to relate to the community, its refusal to support and sponsor equality legislation, and a failure to recruit queer candidates, according to many former party strategists and consultants.

Rich Tafel, who was a longtime Republican consultant, thinks the party doesn’t do enough to cultivate talent. “The party has no pipeline,” he declares. “We’ve lost ground in nurturing young candidates.”

Gunderson however doesn’t see it that way. “I honestly think the party will be happy to support and recruit LGBTQ candidates when and if shown they are the most qualified and competitive,” he counters. “But we have two big problems. First, gerrymandered districts have resulted in primaries where ‘the purest conservative’ wins nomination. This doesn’t help socially moderate Republicans. Second, the gay movement needs to be for more active in building a bipartisan roster of qualified, openly gay candidates.”

And Tafel agrees that work needs to be done on getting rid of extreme polarization — on both sides. “Extremism is a crisis in this country, even with the Democrats, and extremism plays into the fact that Republicans aren’t going to promote a gay candidate, when the base of the party supports anti-LGBTQ laws,” he says.

However, Tafel thinks the Republican Party might be at a tipping point and will slowly start to move away from Trumpism. “More and more, the whole MAGA movement is considered to be dangerous, and they are losing consequence,” he says. “They’re going to hit rock bottom, and then the party will have to undergo a serious reality check.”

Citing his own experience, Gunderson agrees that the clock might be ticking for Donald Trump and the MAGA crowd. “One of the things I learned early in my political career is that every movement needs an enemy,” he recalls. “When I ran for reelection as an openly gay Republican, the garbage thrown against me by conservative opponents was just incredible and despicable. But they were convinced if folks like me got reelected, then gays would become accepted in the party. So today, the conservative social activists continue to use the gay sector as ‘the enemy.’ It works in motivating their base. So the question is, how long will that last?”

“I honestly believe that post-Trump there will be a gradual return to the Republican Party of my time known for limited government, local control, free enterprise, and a strong foreign/defense policy,” Gunderson continues. “When that happens, as the young today become the majority of voters, you will see the party’s positions moderate.”

But someone younger than Tafel, Karger, and Gunderson says Trumpism isn’t going away anytime soon.

“I don’t know that engaging more LGBTQ candidates in the Republican Party is fixable in the current atmosphere of the Republican Party,” argues Tim Miller, a gay former Republican National Committee spokesperson and a writer for The Bulwark, a neoconservative news and opinion website. “In theory, at some of the state levels, which is where you recruit candidates, prospective LGBTQ+ candidates won’t run and buck the system because of all the antigay rhetoric and legislation. And if you are gay, chances are you don’t want to be Republican because of all the party’s vitriol against our community.”

Furthermore, Miller says, it’s a supply and demand issue, and there isn’t a demand for what the party supplies. “The kinds of people attracted to the Trump era are grifters, frauds, aggrieved, bombastic, and phonies,” he says without directly mentioning the name “George Santos.”

And while Tafel and Gunderson think Trumpism might be close to a breaking point, Miller disagrees. “MAGA and its ongoing nationalist white culture war isn’t easily reversible,” he says. “If Trump lives or dies, it’s going to go on. For example, if Nikki Haley runs for the Republican presidential nomination [which she is], there’s hardly anyone in the current party thinking that supports a globalist female. That’s not what the party is anymore.”

But one thing they all agree on is that the Log Cabin Republicans don’t mean anything anymore. “To be honest with you, I never joined the Log Cabin group, and I’m glad I never did,” Miller says. “They’re a tool of Trump now, and as far as I’m concerned, they’re useless, just like the Republican Party. Log Cabin is Trump’s now and will be for the foreseeable future, so we’re not going to see any LGBTQ+ Republican candidates.” Log Cabin Republicans president Charles Moran did not respond to a request for comment regarding the party’s problems with LGBTQ+ candidates and voters.

The ineffectiveness of the Log Cabin group means that there are no guardrails to prevent the party from shifting more toward using social and LGBTQ+ issues as wedges, according to Gunderson. “While Trump has claimed to be supportive of gays, his MAGA movement is made up of very conservative voices,” he says. “While it includes some libertarians who should support our sector, they simply focus on very different issues. Identity politics of any sort is one of their main targets. During COVID, the Republicans became ‘big government conservatives’ in terms of spending. Now these same big government conservatives are engaging in social issues.”

Kirchick tries to push the narrative that Trump was somehow not as bad for LGBTQ+ people than Reagan or the Bushes, though that argument usually comes from a white gay man thinking of only white gay men and not the demonization of trans people and people of color in general that Trump regularly whipped up. Kirchick’s argument may hold less and less weight as the 2024 election draws near; Trump has already made attacking trans youth and gender-affirming care a centerpiece of his third presidential run.

Any moderation Trump showed on LGBTQ+ rights “may change if he goes up against Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who has made anti-LGBTQ legislation a focal point,” Kirchick admits. “Trump may have to try and match DeSantis. If DeSantis gets the nomination, you definitely won’t be seeing any gay candidates, particularly at some of the state levels, where state legislators are taking their anti-LGBTQ legislation leads from Florida and DeSantis.”

But that might not include Wyoming, an anomaly of sorts, according to one of its Republican state representatives, Dan Zwonitzer, who has been out since 2016 and continues to be reelected. “Admittedly, the last two election cycles have been a bit tougher for me,” he says. “However, historically no one in the legislature or even my constituency treats me any different because I’m gay. What might be worse to them is that they treat me more as a moderate. That’s why I see a schism for both parties who are becoming more extreme and less pragmatic.”

While Wyoming is overwhelmingly Republican, Zwonitzer says the state is a bit insulated in some ways from a lot of the national political dialogue. “This is a small state. We all know each other,” he says. “On a local level, my district includes the state capital, and many of the residents reflect the old Republican Party’s attitudes. We’re not necessarily part of the new Republican Party. We don’t follow the mandates of the state party platform and the national platform. Both have gone too far, and the planks don’t represent what we stand for, at least in my district, and of course, I hope that holds true.”

“The political environment has become so vitriolic and demands allegiance to one individual rather than doing the right things to move us forward,” he continues. “And one reason we are not seeing more LGBTQ+ candidates is because they must pass a litmus test about whether they have allegiance and support the orthodoxy, and who knows how long this will last.”

The 2022 midterms made history when Democratic congressional candidate Robert Zimmerman faced another gay candidate, Republican George Santos, in a district on New York’s Long Island. In an interview with USA Today, Log Cabin President Charles Moran said Santos represented diversity within the party and the LGBTQ+ community. “There really is a lot of diversity in the LGBT community in political thought,” Moran said.

For his part, Santos told the paper, “I’m a gay married man. I am openly gay, have never had an issue with my sexual identity in the past decade, and I can tell you and assure you, I will always be an advocate for LGBTQ folks.”

Since he was elected, the only thing Santos has advocated for has been himself, according to Miller, while everything about him, including his sexuality and party affiliation, among many other things, has been called into question. “George Santos doesn’t believe in anything,” Miller says unequivocally. “He could have just as easily run as a Democrat and pretended to like Obama, but the competition on the Democratic side was too steep, so Santos took the easy way.”

Gunderson, who is arguably the dean of gay Republican legislators, thought at one point the Republican Party might be shifting, and while it didn’t, he now has hopes that future generations will save the party. “Around the years 2014—2016, there was evidence that Republicans were becoming more accepting, and Republican voters, according to polls, appeared to be more welcoming to gay candidates,” he says. “For example, by 2014 over 60 percent of Republicans between 18-29 supported [marriage equality]; and even 52 percent of Republicans up to 50 supported [marriage equality].”

“I think in time, as the younger generation comes of age, and they start running for office, and occupying more legislative seats, things might change,” Gunderson predicts. “This generation all knows someone who is gay, and their attitudes are much more progressive. At least that’s my hope, and the hope of my generation of fellow Republicans who are counting on it.”

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.