Surgeons at John Hopkins University have performed possibly one of the first kidney transplants from a living donor with HIV in the Unites States.

Both the donor and recipient are HIV-positive, reports The Associated Press, and according to their doctors they're recovering well.

John Hopkins has spearheaded HIV-to-HIV organ transplants since 2016, after first receiving approval from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) to perform two transplants (one kidney and one liver) from a deceased HIV-positive donor.

This the first time the procedure had been performed since the 1988 Organ Transplant Amendments Act, which prohibited poz people from becoming donors.

According to UNOS, 116 such kidney and liver transplants have been performed in the U.S. as part of a research study. So far, there hasn't been any mishaps between HIV-to-HIV transplants despite concern that organ donors with a different strain of HIV than a recipients' might pose risk.

"Here's a disease that in the past was a death sentence and now has been so well controlled that it offers people with that disease an opportunity to save somebody else," said Dr. Dorry Segev, a Hopkins surgeon who pushed for the HIV Organ Policy Equity, to AP, adding: "There are potentially tens of thousands of people living with HIV right now who could be living kidney donors."

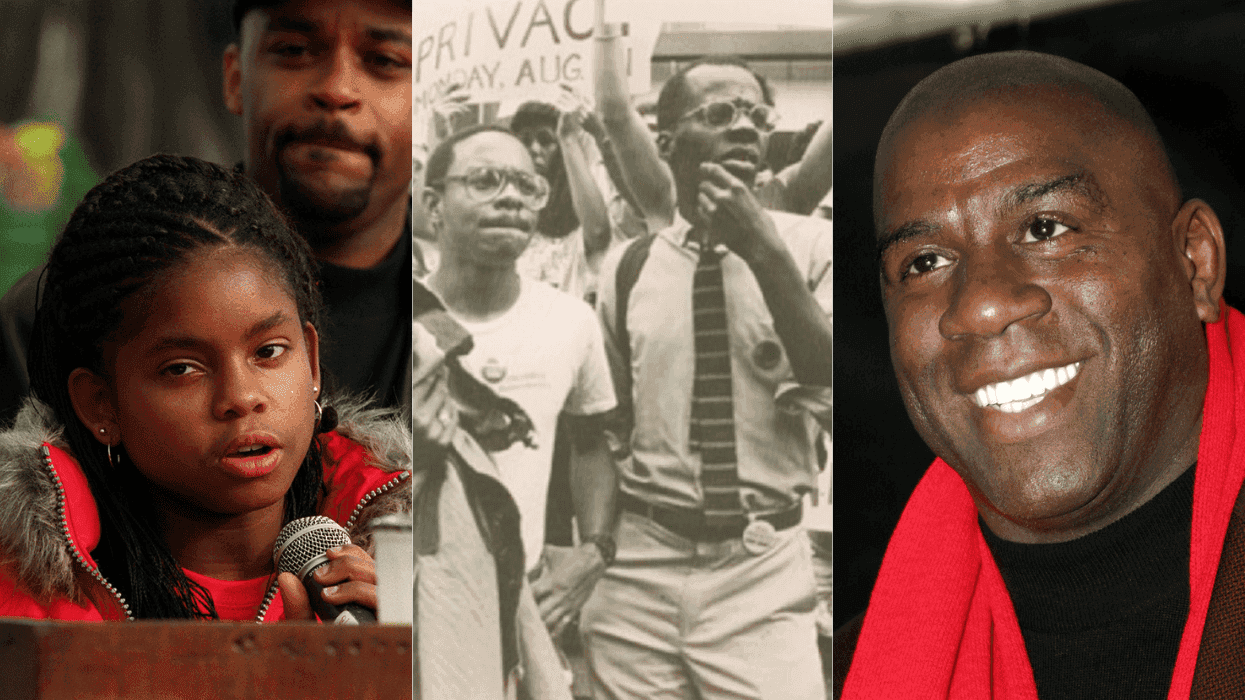

Nina Martinez, the HIV-positive donor, was drawn to living organ donation long before she discovered her status. Martinez personally reached out to Dr. Segev to ask if she could donate after learning that her friend (who was also HIV-positive) needed a transplant. Unfortunately, the friend died before Martinez finished the hospital's required health tests.

To honor her late friend, Martinez decided to continue the path of donating her kidney. This time, to a lucky stranger.

Many people think "somebody with HIV is supposed to look sick. It's a powerful statement to show somebody like myself who's healthy enough to be a living organ donor," Martinez said. "I knew I was probably just as healthy as someone not living with HIV who was being evaluated as a kidney donor. I've never been surer of anything."

Doctors have raised concerns about living HIV-positive donors, versus deceased HIV-positive donors. The main argument has been that those living with the virus might have damage from older medications, which might place the recipient at risk. But as more successful transplants take place, the closer we are to showing that living poz donors who are undetectable are just as healthy as HIV-negative donors.

Hopkins' procedure is the latest in slew of groundbreaking operations across the world.

As Plus magazine previously reported last year, surgeons at Wits Donald Gordon Medical Center in Johannesburg, South Africa, performed the first transplant in the world from a living HIV-positive donor to an HIV-negative child (who happened to be a mother and her child).

A South African child was born with a birth defect that restricts blood to the liver, reported Bhekisisa. While the child had been waiting for a transplant for 180 days, the mother (who is HIV-positive) was offering to donate a portion of own liver. Doctors at first refused to do the surgery until the mother pleaded with them to reconsider.

The mother, who is undetectable, pushed back at the lead surgeon, Jean Botha, arguing that he was intentionally "excluding" her because of her status. Botha later explained to reporters, "We were under the presumption going into this that the child would develop HIV. That was the ethical debate: We had to balance the benefit of saving the child's life against the risk of [contracting] HIV."

According to reports, the night before the transplant the infant was given a combination of three antiretroviral drugs to help prevent HIV transmission from the donated liver. Botha said the drugs could have halted the transmission, but that the child will continue to be monitored to confirm the virus remains suppressed.

A year later, the child has shown no evidence of HIV in their blood, according to Caroline Tiemessen, who heads the Cell Biology Research Laboratory at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases Center for HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections.

According to HIV.gov, up to 30 percent of those living with HIV suffer from abnormal kidney function issues, which, left untreated, could turn deadly. In 2016, the number of HIV-positive donors is estimated between 500 and 600, according to the New York Times. Those donors could potentially save nearly 1,000 people a year if the law allowed them to donate their organs to HIV-negative recipients.

While the HIV Organ Policy Equality Act, signed by President Obama in 2013, legalized transplants between poz people, it continues to place poz recipients at a disadvantage since laws limit them to only receiving organs from donors who are HIV-positive.

Over 113,000 people are currently on the nation's waiting list for organ transplants.