If the people lead, the leaders will follow.

It's an oft-repeated adage, but it's often accurate -- and it's definitely true about the movement for marriage equality.

While major LGBT rights organizations have gotten on board with the movement and aided immeasurably in its progress, the impetus in several key cases came from the grassroots -- ordinary people who've sought marriage rights when movement leaders thought it wasn't the right time or the right case to make the argument for equality. From three couples in Hawaii to a New York widow to a Michigan couple seeking to protect their children, they've brought the U.S. to the verge of nationwide marriage equality.

"There's never a wrong time to fight for one's rights," says Dana Nessel, the Detroit attorney who originally took the case of April DeBoer and Jayne Rowse, one of the couples whose plea for marriage equality will be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court Tuesday.

The fight for marriage equality has been going on for decades, but even when Rowse and DeBoer filed their suit in 2012, no one imagined the swift progress that's occurred in the past two years. And there were those who had their doubts the women would win at the trial level, much less be taking their case to the Supreme Court.

They decided to go to court in the aftermath of a near-miss on a snowy road in 2011. Their minivan was nearly in a head-on collision with a truck that was trying to pass another vehicle on a rural road. The truck swerved into a field at the last moment, sparing the two women and their three children (they have since adopted a fourth) from what would likely have been a fatal crash.

That brush with mortality led Rowse and DeBoer to consider what would happen to their children if either or both of them died. Michigan law does not allow unmarried couples to jointly adopt children, so each of the women, both Detroit-area nurses, is legal parent to two of their children. Through one of their online parenting groups, they got a referral to Nessel and started working on wills and other legal documents. But they found out a judge could easily ignore such documents.

In January 2012 they sued in U.S. District Court in Michigan, challenging the state's adoption code. Judge Bernard A. Freeman told them they really should be challenging the ban on same-sex marriage instead -- and gave them 10 days to do it.

"We really are the accidental Supreme Court case on marriage equality," says Nessel, who herself came into the fight rather accidentally. When she went into private practice focusing on criminal defense work after experience as a prosecutor, she found that many of her clients were people accused of stalking and violating orders of protection simply because they wanted to see the children they had parented with a former same-sex partner -- children to whom they had no legal relationship because of Michigan's laws.

DeBoer notes that early on in their legal battle, they approached a couple of Michigan civil rights groups -- she declines to name names -- and were told it was the wrong case, the wrong time, etc. It was a different environment then, she notes -- the landmark 2013 Supreme Court ruling in Windsor v. U.S. and the rash of marriage equality rulings it spurred were yet to come.

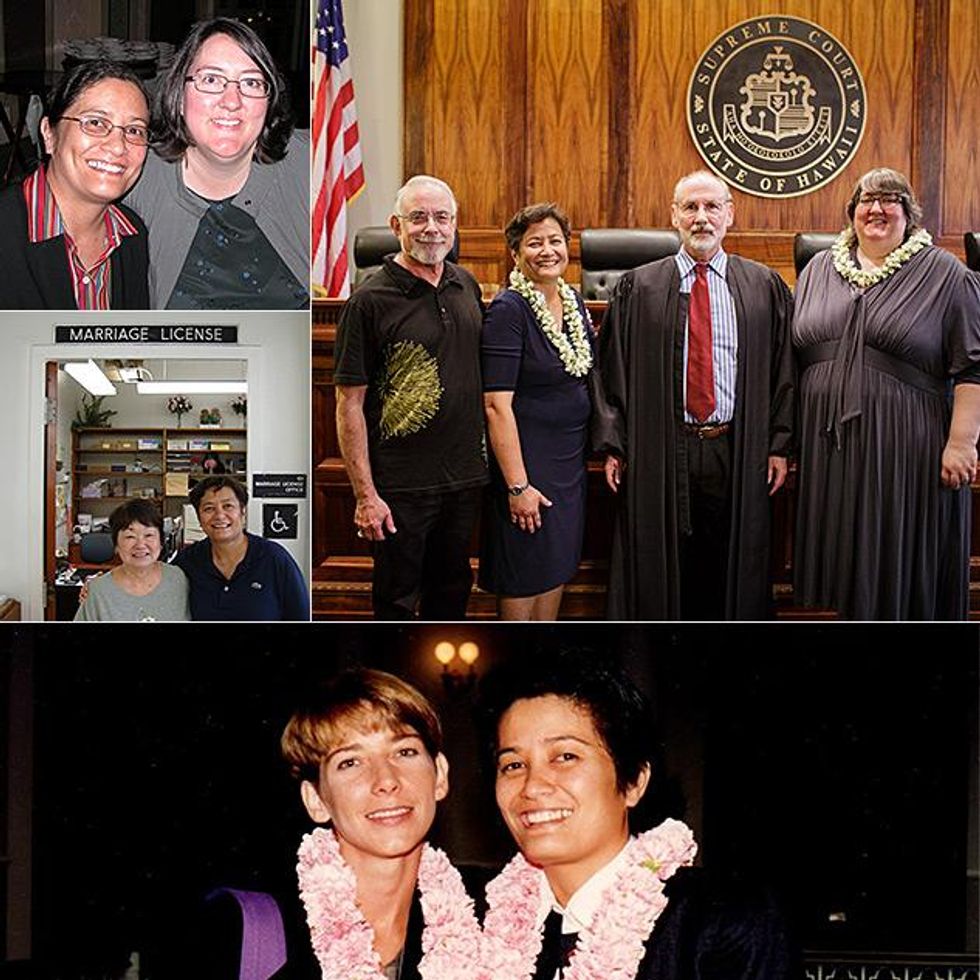

Those rulings were even farther in the future when three Hawaii couples challenged their state's ban on same-sex marriage in the early 1990s. One of the couples in that case, Ninia Baehr and Genora Dancel, had met and fallen in love in 1990. The impetus for them to seek marriage rights was not just romantic but practical. Baehr came down with a bad ear infection; she was working part-time and had no health insurance. Dancel was working two full-time jobs and had access to insurance through both, but she couldn't put Baehr on it. She contacted the local gay community center, and an activist named Bill Woods answered the phone. He suggested they apply for a marriage license.

"My whole life just sort of flashed in front of me," Dancel recalls today. "I got tired of being a second-class citizen."

The next day, December 17, 1990, they and two other couples -- Tammy Rodrigues and Antoinette Pregil, and Pat Lagon and Joseph Melillo -- went to the State Health Department in Honolulu and applied for marriage licenses. They were denied.

"We were not very sophisticated activists," Baehr says. "We were in love and we wanted to get married."

The couples then contacted the Hawaii chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU officials asked if they would settle for pursuing domestic partnerships; the couples said no, marriage. The ACLU didn't have the resources to pursue such a case.

"This was at a time when no national gay organization wanted to take on this issue," Baehr says. She and Evan Wolfson, then an attorney with Lambda Legal, had a mutual friend, and she approached Wolfson, who was an early advocate for marriage equality -- he had written his law school thesis on it. He was interested in representing the couples, but "Lambda refused me," Wolfson says. Lambda's leaders "all felt, for a mix of reasons, that it was not a good idea."

At the time, Wolfson explains, across the LGBT rights movement, most leaders thought seeking marriage rights would be going too far, too fast, would trigger more discrimination, and might derail other movement goals. Then there were some who thought marriage was not a goal worth pursuing -- they saw it as patriarchal and exclusionary, or believed gays and lesbians should maintain an "outlaw" status.

However, the fact that Lambda wouldn't let Wolfson take the case, he says, actually turned out to be a good thing for the Hawaii couples. "It led them to Dan Foley, who was a terrific attorney to do the case," Wolfson says. Foley was a civil rights attorney who had formerly worked for the ACLU of Hawaii, and he knew the state well and was ideal to argue the case. The couples in the case held fundraising parties to pay his fees. "He billed us for a portion of his time and we paid a portion of his bill," Baehr says. And Lambda agreed that Wolfson could assist Foley behind the scenes.

The path of the Hawaii case was one of steps forward and back. The couples filed suit in 1991 and the trial court dismissed it within a few months, but in 1993, on appeal, the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that excluding same-sex couples from marriage was discrimination based on gender, then sent the case back to the trial court with the directive that the state had to show a compelling interest in justifying such discrimination. "The earth moved" that day, Wolfson recalls. "This was the first time ever that a court had taken seriously the freedom to marry" for same-sex couples. (It should be noted that the Hawaii case was not the first to seek equal marriage rights; that distinction belongs to Baker v. Minnesota, a case filed in 1970 by Jack Baker and Michael McConnell. And there were cases seeking marriage rights in Kentucky and Washington State in the 1970s. But the Hawaii case was the first to receive a favorable ruling.)

After the 1993 decision, Lambda let Wolfson join the case as Foley's co-counsel, and then in 1996 the trial court ruled that the state had not made a convincing argument for discrimination. While the state appealed, though, Hawaii voters passed a constitutional amendment, in 1998, allowing only the legislature, not the courts, to make law on marriage -- finally rendering the case moot.

Still, as Wolfson and the plaintiffs point out, it was a major step forward. "There's no question, the ongoing global movement for the freedom to marry ... all of that was launched by the Hawaii case," says Wolfson, now president of Freedom to Marry, an organization he founded.

Adds Baehr: "This is definitely a case of if the people will lead, the leaders will follow."

There was some of the backlash movement leaders had feared. While the Hawaii case was going on, legislatures around the nation rushed to pass laws making it clear that their states would not allow same-sex marriages -- even though no state had to date -- or recognize such marriages performed elsewhere. And President Bill Clinton, up for reelection in 1996, signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act, assuring that the federal government would not recognize same-sex marriages and allowing states to opt out of recognition.

But the marriage equality movement refused to die. Several groups took up the cause, including Lambda, Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, the National Center for Lesbian Rights, and the ACLU. Still, some saw their quest as quixotic. "In 2003, people thought we were going for the impossible," says GLAD executive director Janson Wu. That was the year GLAD won Goodridge v. Massachusetts, the case that made the Bay State the first in the nation with marriage equality when the ruling went into effect the following year.

There was some of the same backlash; in the next few years, states that had enacted statutes against marriage equality passed constitutional amendments to provide a stronger defense. Conservatives in Congress sought to enact a federal constitutional amendment. Marriage rights were a wedge issue in the presidential race between George W. Bush and John Kerry. Both opposed marriage equality, but conservatives didn't trust Kerry to maintain that position. Kerry, now Secretary of State, did endorse marriage equality in 2011, while still a U.S. senator. That was a year before President Obama announced his support for equal marriage rights.

Windsor, like the Hawaii plaintiffs, met resistance from LGBT rights groups when she wanted to go to court. "To hear her tell it, she was turned down by a number of the organizations," says Roberta Kaplan, the attorney who ended up taking her case. Reportedly, some thought a case with multiple plaintiffs would be a better way or challenge DOMA, or that Windsor was too wealthy to be sympathetic. But Kaplan, who had argued a marriage equality case in New York State that resulted in a loss in 2006, saw in Windsor the perfect plaintiff.

Windsor and Spyer had been together since the 1960s, and Spyer was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1977. Windsor cared for her partner as Spyer's health declined; eventually Spyer needed a wheelchair and an oxygen mask. When it comes to for better, for worse, in sickness and in health, "they were really two women who lived those words," Kaplan says. Also, she notes, "no American likes paying taxes," and the taxes levied on Windsor seemed particularly unjust. Plus there is Windsor herself: "her beauty, her charisma, her intelligence," Kaplan adds.

They filed suit in 2010 and it went to the Supreme Court in 2013, resulting in the court striking down the portion of DOMA that denied federal recognition to same-sex marriages. The same day it announced the Windsor ruling, June 26, 2013, the high court also announced it was letting stand a lower court ruling striking down Proposition 8, a California ballot proposition that voters had approved in 2008, revoking marriage equality in that state.

That case had also met some movement resistance; after the California Supreme Court refused to void Prop. 8, several LGBT rights groups (including NCLR, Lambda, GLAD, the ACLU, the Human Rights Campaign, and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force) advised against challenging the law in federal court, deeming such a suit unlikely to succeed. They recommended putting the question before voters again. But a new group founded especially to challenge Prop. 8, the American Foundation for Equal Rights, pursued a federal case with counsel from high-profile lawyers David Boies and Ted Olson, and the rest is history. (By the way, AFER cofounder Chad Griffin is now president of HRC.)

That said, LGBT rights groups now generally back the fight for marriage equality, even though, as always, there are some differences over strategy. Among the cases the Supreme Court will hear today, the ACLU is representing the Kentucky plaintiffs; both the ACLU and Lambda are involved in the Ohio case; and the NCLR is handling the Tennessee case, while private attorneys have worked on all three as well. Many groups that don't handle litigation have filed friend of the court briefs. And GLAD's Mary Bonauto has joined the Michigan case and will argue it before the high court.

The fight for marriage equality "was inspired and certainly came from grassroots efforts," says Wolfson, but gay rights institutions have embraced it. "It's important to respect the grassroots piece and it's important to respect the strategic piece," he says.

After the DOMA and Prop. 8 rulings, the floodgates opened. Through court rulings and legislative action, 37 states and the District of Columbia now have marriage equality. And a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court in the cases it hears today could result in equality nationwide; the ruling is expected in June.

DeBoer and Rowse, along with plaintiffs in the three other states, had won at the trial level but lost when their states appealed to the Sixth Circuit, leading to the Supreme Court hearing. The women and their attorneys are cautiously optimistic about the outcome. Three other private attorneys have worked with Nessel on their case, and now Bonauto will represent them before the Supreme Court. "We're excited to have Mary leading the charge for us," Nessel says.

For those who've been involved in other marriage equality cases, there have been some happy endings. Hawaii legislators approved marriage equality in 2013. Dancel and Baehr are no longer a couple but remain good friends, and both are now married. Dancel married Kathryn Dennis December 17, 2013, in Honolulu, 23 years to the day after she and Baehr were denied a marriage license. Dan Foley, now a judge on the state's Intermediate Court of Appeals, officiated. Retired Hawaii Supreme Court Justice Steven Levinson, who wrote the 1993 pro-equality ruling, was a guest. Baehr and Lori Hires married last Christmas in Montana, which gained marriage equality in November. Tammy Rodrigues and Antoinette Pregil are still together and married. However, Patrick Lagon's partner, Joseph Melillo, died in 2006.

Those pioneers in Minnesota, Jack Baker and Michael McConnell, are still together after many years and are legally married; they are working on a memoir, to come out next year, and are not giving interviews until then.

DeBoer and Rowse now hope their wedding day will come soon. "We're excited and we're nervous," DeBoer says. Noting they've been on a "crazy journey," she adds, "We have to be optimistic about what we're doing. Jayne and I are not negative people. We feel optimistic that we will gain marriage equality in the United States and be a legal family in Michigan."

And for those who had doubts about the case, Nessel says, "It's never too early to fight for one's constitutional rights. I hope this case will be a lesson to everyone."

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.