On a hot October day, I get a text from Eileen Myles: "I'm free now. I'll go to 17 & Pico."

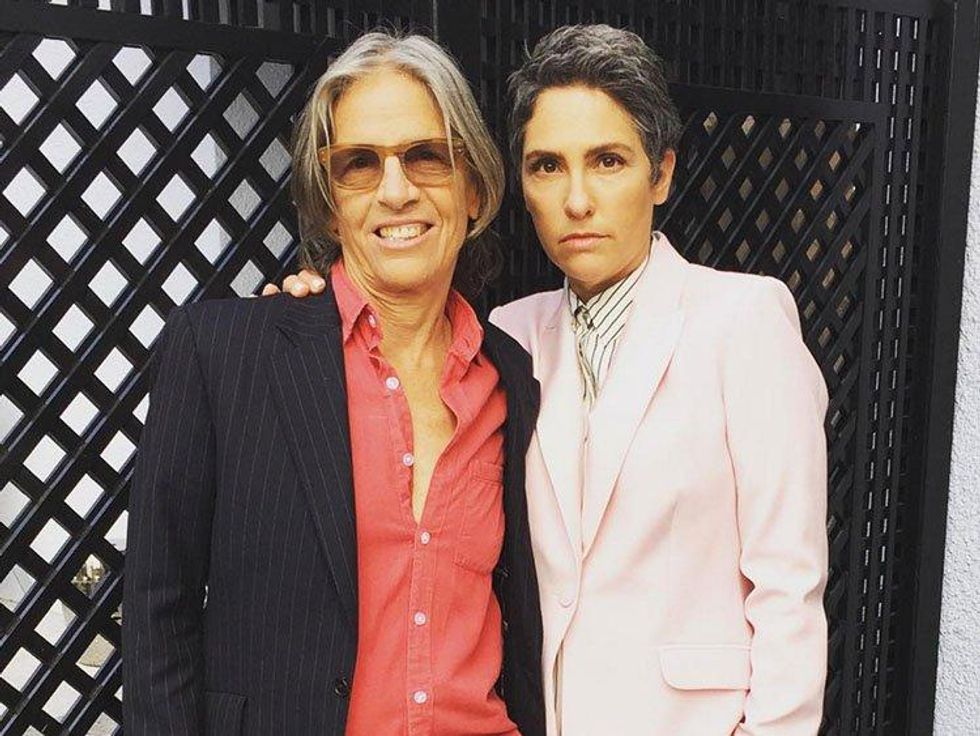

I'm meeting the 65-year-old poet in Santa Monica, Calif., where she has just finished doing a radio interview. We have our own interview scheduled, which will take place in my car, on the way to the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, where Eileen is eager to get to her girlfriend, Jill Soloway, the creator and director of Amazon's Transparent. But I don't actually know that part yet.

Dressed stylishly in a blue- and white-striped button-down shirt and rolled-up pants, and carrying a tan rucksack, Eileen steps into my two-door red Ford Focus.

It is a hot and sticky Los Angeles day, nearly 100 degrees, and unfortunately for both of us, my air conditioner isn't functioning. The breeze off the Pacific Ocean isn't enough to keep my hair from sticking to my face, but I'm trying to be cool, wiping sweat off my brow, hoping Eileen doesn't notice. I never open my sunroof because it usually gets stuck, but I don't want to be responsible for suffocating the legendary poet, so I open it.

We make small talk about Los Angeles and New York's poetry scenes as we merge onto the 405 freeway. "Here we go, right into the beast of traffic," I say, annoyed as I look over the smog building above the hundreds of cars lined up at a standstill, all of us trapped in the middle of the 4 p.m. rush-hour traffic in the high heat of the afternoon.

As I'm doing my best to split my attention between the gridlock and recording our conversation, we both fall silent. The right blinker is clicking rhythmically when Eileen looks outside the passenger window, and says, "Let's face it. The best American poets are all gay."

She names them off in succession, as if she had the list prepared in her mind: Langston Hughes, Allen Ginsberg, Aimee Lowell, Muriel Rukeyser, Elizabeth Bishop, Frank O'Hara, Essex Hemphill, Tim Dlugos, and Judy Grahn.

"Everybody's gay," she says as we go under a concrete overpass.

Eileen has pulled up her knees to her chest. You might as well add yourself to that list, I think silently.

Out loud, I ask her, "Why are America's greatest poets gay? Could it be because when you're gay, it feels like you are going through some sort of second emotional puberty, where you no longer have to deny same-sex attractions or pretend you are straight, after coming out?"

"Yes," Eileen agrees. "We have these subterranean lives. We just grow and develop for years before we ever speak. I feel like there is this whole welter of language happening, and when you start to write, it just pours."

After decades writing and publishing, mainstream buzz around Eileen has picked up recently, since HarperCollins reissued her iconic coming-of-age novel about her "lesbian daily life" (as she calls it), Chelsea Girls, and released her collected poems, I Must Be Living Twice.

The New York Times aptly dubbed Eileen the "poet muse" of Transparent. The show featured Eileen's poem, "School of Fish," read by a character clearly inspired by Eileen: a women's studies professor and poet, played by out actress Cherry Jones. In Transparent, Jones wears a vest, keeps her silvered hair disheveled, and sports a toothy, mischievious grin that seems like it would be at home on Eileen's face.

After watching Jones play a character based on "Eileen Myles," the real Eileen Myles wrote a poem about the experience of watching herself be watched by other people, through the eyes of someone playing her. The entire scene is very meta, since Eileen is an extra in the background, sharing the screen with Cherry's character.

As we're veering through traffic, taking surface streets to get to the Silver Lake Reservoir, I've once again just turned on my blinker when Eileen offers another unprompted observation: "Part of the reason I'm sure I wasn't published by a larger publisher until now is because I'm queer."

"Are you sure?" I ask, knowing that I believe her but wanting to hear her response.

"Absolutely sure," she replies without hesitation. "The word pussy appears seven times in my collection of poems. I'm sure the word pussy has never appeared in any other mainstream poetry book at all."

Eileen has never been afraid of offending anyone. "If we [lesbians] band together, they call it separatism, but when men do it, they don't call it that," she observes. "It's just men. It's just masculinity."

I can't argue with that, because she is not wrong in lamenting how many magazines cater exclusively to the gay male audience -- even magazines that outwardly depict themselves as catering to the full LGBT experience.

"There are magazines that exist solely to cater to gay men," I say. "No one would ever call that separatism. Out magazine is largely focused on a male audience, but no one would ever call Out a gay separatist magazine."

"Exactly!" she yells excitedly, before turning back to her memories.

"I remember being at some awards ceremony, probably 15 years ago, when there was a new gay/lesbian award and they gave an award or more than one award," she recalls. "It was a gay man who gave it to a gay man."

The poet shifts in her seat, lifts her leg from the dashboard, and sits up straight. "I remember that was the moment I thought, You're the separatists."

"We're not," she says quietly, with a tone that carries sadness.

Sitting in the middle lane at an intersection to turn right, Eileen's mood shifts, and I forget about the noise and movement of the city around us. I am envisioning Eileen at this fancy event, where they invited her and other literary darlings for this momentous occasion, to celebrate LGBT authors, only to have her sink low in her seat. I am struck by how queer women still fail to get recognized in the literary world.

"When Chelsea Girls came out, I really got criticized for writing about my lesbian daily life, like, That's important?" Eileen recalls. "The disturbing thing was my existence."

"Damn," she says softly, as if coming to that realization for the first time, again. "That was the problem. But nobody was going to say that. Who the fuck wants to hear about her?"

With a sly grin, Eileen looks me in the eye, as if she is speaking to the literary gatekeepers. Wryly, she offers, "Oh, I should shut the fuck up, right?"

I have to ask her why she didn't do exactly that. What kept Eileen writing, long after feeling excluded from the literary world for writing about her "lesbian daily life"?

"I knew I was better and smarter than the people who were saying that shit," she answers confidently.

She maintains that confidence as an armor she's still using to defend against critiques she sees as misguided. When her collected poems were reviewed in The New York Times, she wasn't thrilled.

"The guy who reviewed me spent half the review talking about pictures of me," she says. She wasn't bothered by that as much as she was by his statement that "about halfway through, the work really gets weaker."

"It's not true, it's just not true," she repeats, obviously bothered by the literary dig.

Ultimately, she appreciated the review because a critique in The New York Times exposed her to a new audience, and "it meant that I was important," she says.

"It's like I'm having this big publicity moment right now, and it's really just about the fact that I'm being published by a mainstream publisher now," she explains. "I was in indie presses my whole career, and now HarperCollins has said, 'She matters.' And so suddenly I matter, and the narrative is, 'Used to be a punk poet, lesbian poet!' 'Used to be at small press, and now she's at HarperCollins!' Like, that's the story."

What Myles sees as a retrospective of her literary career is being billed as a "crossover moment," she says. "That's just what creates publicity, so I'm happy about it."

While New York magazine, The New Yorker, and others are writing glowing reviews of the work by the "punk poet," Eileen has a bigger question: Why did it take 19 books and almost 40 years for her to get a mainstream book deal?

That's what people should really be asking about, not celebrating that she's having a "moment," she argues. Readers should be thinking about how hard it is for women, even revered and celebrated women poets like herself, to get an "in" to the mainstream publishing world. Executives at her own publisher were surprised they had to reprint the book five times over already.

"Surprised? I'm famous," she says confidently. "Did they think nobody would want to buy my book?"

This takes me by surprise, and I ask her if she wants to be famous, "Like Truman Capote and Gore Vidal, who were on late-night TV -- back when writers were celebrities?"

"Of course," she replies. "Who doesn't want to be famous? I am famous. I'm dying to be on TV."

The intellectual curiousity Eileen brings to every conversational topic, even the menial things that the rest of us pass over, is beguiling. This eagerness to discuss and intellectualize everything is what makes her such a compelling, charming figure to sit down with -- even if it's on a really hot day, in a car with no A.C.

As a child, Eileen dressed up as a beatnik every Halloween. Her motivation was twofold: to be an alternative character, but also to be a boy. "I wanted to grow up to be that," she says.

By the time she was in college, she'd perfected a punch line about her profession. "I'm using my degree," she'd say. "You know, I studied English and American literature in college and now I'm an American poet."

Then Eileen says, "It's your own people who get you the most." She's referring to critics who don't understand where she's coming from, thinking she's just arrived at this destination, when she's been at this game all along, hacking away at poems about pussies and poems about the Kennedy administration, and poems about "dykes" for decades before the mainstream press "discovered" her.

But the world of mainstream publishing wasn't ready for her, says Eileen. Publishers are more willing to publish gay men because it will get them somewhere, she says.

Eileen and I stop next to the Silver Lake Reservoir to finish our conversation. She tells me about what it was like being a young, queer, and broke poet in New York in the '70s. Everyone was willing to buy her a beer, but no one ever thought to offer to buy her food. So she would steal from her local bodega, she tells me as I start the car.

We go toward the hills, on the way to her girlfriend's place. I don't realize it at the time, but I've pulled up to Jill Soloway's house. It will be another two months before Soloway comes out about dating a woman (Eileen, specifically), in a revelation buried deep in a glowing profile of the Transparent showrunner in The New Yorker.

As I put the car in park, Eileen invites me to a book launch party hosted by her girlfriend in Silver Lake. I've got other plans, so I sadly decline. Then, with a warm smile, Eileen tells me that she feels like she knows me after our conversation.

"Me too," I say, as she grabs her backpack and waves goodbye.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.