Jim Verraros and Jai Rodriguez are survivors.

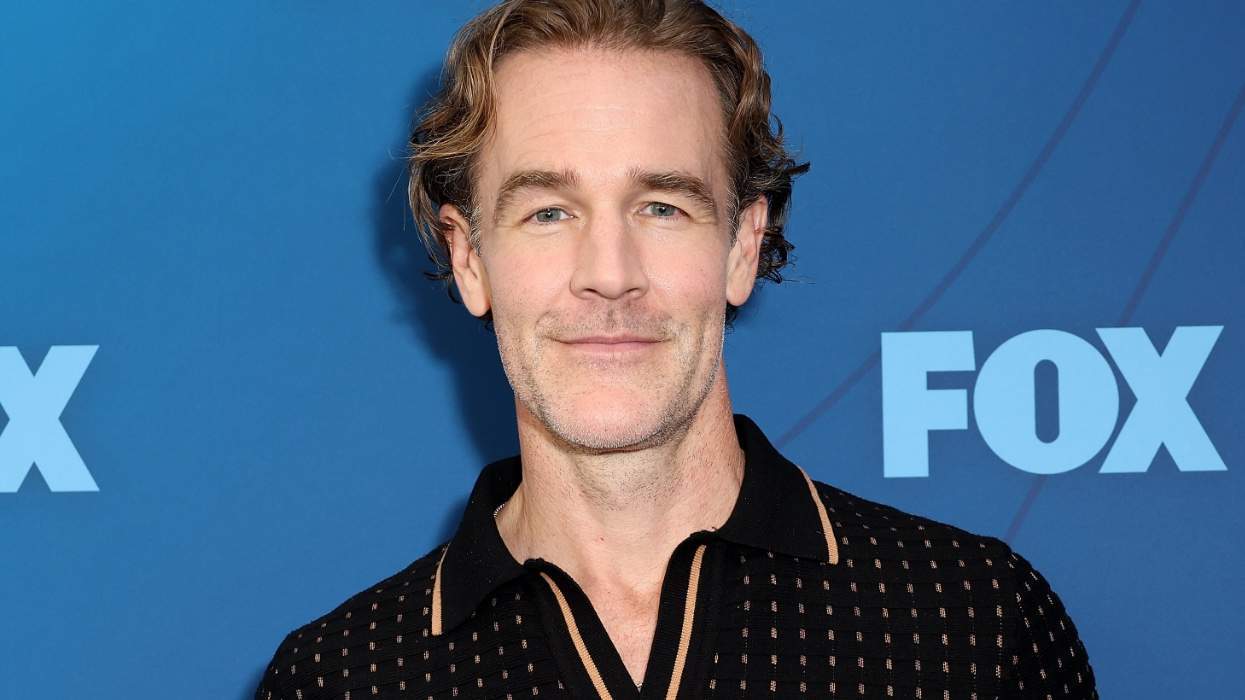

As queer entertainers and public figures, they each became household names during an era when there was far less LGBTQ+ visibility — and also public acceptance of the community was even more fraught than it is today. Verraros was a standout on the first season of American Idol in 2002, where he endeared himself to audiences not only through his immense vocal talent but also his vulnerability. During his time on the megahit reality show, Verraros was open about his experiences as the child of two Deaf parents, and that same honesty would foreshadow an even bigger disclosure: that he was gay. After the season ended, he became the first former Idol to come out publicly. Overnight, he became one of just a handful of out LGBTQ+ musicians performing in mainstream pop.

As Verraros releases his first EP in 14 years, Explicit, he is joined in conversation by Rodriguez, his longtime friend and fellow queer industry stalwart. A member of the original cast of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, Rodriguez has an eclectic career spanning television, music, and film, but the road has rarely been easy. Before booking his own regular cabaret show, he was told, “Boys don’t sell. Gay boys will not support gay boy performers.” He auditioned six times to play one of Lady Gaga’s “gay besties” in A Star Is Born. “Some of the biggest TV roles and movies, I went in for that,” he tells Verraros.

In a wide-ranging discussion, the two LGBTQ+ trailblazers discuss what it takes to survive as a queer person in a harsh industry, changes in queer representation over the past two decades, and continuing to fight for space for themselves. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related: The Queer Eye Reunion That Will Shake Your Foundation

Related: 42 LGBT People Who Made Reality TV History

Jim: I want to start out by saying just what a trailblazer that you've been for me. You had Queer Eye in 2003, which is probably how most people learned about you from a national stage. But what people don't understand is that you came right out of high school and you did Rent on Broadway. That was your kickstart to having this career in entertainment. Tell me about how that started and what kind of came after for you.

Jai: In the early aughts, when you look how I look, the only roles people ever said were right for you were like, “Oh, let’s just hope West Side Story comes back and then you can play a lead.” Playing Angel, visually, aesthetically, I was so perfect. I remember the casting director — I had no agent, I was right out of high school — he was like, “Why have I never met you?” And I was like, “I didn’t have a headshot.” He said, “I would have hired you without all that stuff,” and I didn’t know that. I obviously had a different sound than traditional musical theater. I could cosplay musical theater quite well, but I'm not coming out the gate swinging like Ben Platt. It's a different sound. When Rent came along, it was an incredible fit for me.

Jim: Once the success came to be, it caught like wildfire. Everyone that I knew had the soundtrack blaring at some point. What happened after that? I really don't know when you came out publicly or even ever did, but was there a pressure for you, now that you had this success, to decide at that point,OK, I am gay. I’m playing this gay character. Is this the moment, or do I just sort of keep chugging and kind of let that be secondary?

Jai: Do you know that viral TikTok song “I’m Not Gay, But I Do Gay Stuff?” I was giving that energy back then. You have to remember, it was pre-social media. There weren’t people who were asking too many questions. Obviously, you play a drag queen in a show. The assumption is that you are gay, but the truth is, I hadn’t even done gay stuff. My first gay experience was with a costar in the show who was older than me. I knew who I was, but I didn't have the language. I had no visual representation. The internet was new. It took 47 minutes to download a picture of a naked man. You’d get 42 minutes in, and all you've gotten is a nipple so far.

I knew in my heart and my soul who I was, and I’m thankful that I had a cast of people that were really gentle with me, but I will tell you the inner homophobia playing a drag queen in the show, in 1997. I definitely was still hooking up with girls, making that really complicated. I was having sex with women through even Queer Eye — because drag queen, then the queer guy from Queer Eye, it was just so much inner homophobia. I grew up strict evangelical, born-again Christian, so I didn’t have access to things that were outside of that. I think my coming-out journey was a quiet one until Queer Eye, but the reason why I took it was because no one watched Bravo. I did Watch What Happens Live a couple years ago, and Andy Cohen was reintroducing me after commercial, and he's like, “You guys built this house,” which is true, it wasn’t a big deal. I thought, If I take this little show that no one's gonna watch, I'll get a little extra money and that'll be it. Even the other guys, some of them hadn't come out to their parents officially. It was a different era back then in the early 2000s.

Jim: When I was on American Idol, this was 2002. This is the year before Queer Eye premiered. No one can prepare you, or no one can really tell you, what it's like to be thrust into the public spotlight. For me at the time, coming from a small town in the suburbs of Chicago to two Deaf parents … my father was born in Greece, emigrated to the States when he was just 3, hard of hearing, so a very difficult childhood, but no one really tells you how to accept yourself in front of the world. You know that you're different, and yet here are all these people that are sort of pointing fingers because they feel that you're different, you're other. At that time, it was just trying so, so hard to not be as gay as I knew I was. It was an instant awareness of every camera though that was around me: Bring the voice down. Don't talk with your hands. Be less expressive. I just didn't want it to hinder anything that could happen from my success on the show.

Jai: The caveat to doing Queer Eye was, Our intention is to celebrate you as gay rock stars. We were edited that way, dressed that way, positioned that way, and the world accepted us that way. From your angle, you obviously were in a position where it was discouraged, right?

Jim: I used to keep a LiveJournal, and I was going to school. I was very out. I talked about going on dates with guys. Once I landed Idol, they found it and instructed me to delete it. Before I had a chance to take it down, someone had copied and pasted every single entry I ever put out and then put it on a separate website. It was a done deal. My father didn't even know I was gay yet. I told my mother and my sister when I was 18. I said, “Keep this to yourselves. I will tell him when I'm ready.” And they said, “OK, of course.” It was always this lingering feeling of, Just don't say anything and don't let it hurt your chances. I don't think people know this, but most of the voting comes from red states in the United States. The blue states don't really watch Idol. They don't really vote. They're not really that invested. I wanted every opportunity, and I didn't want to screw it up.

Jai: The irony of that is, our key demographic was the same voters that voted for you. They were the people that loved us. They supported President Bush, who was against marriage equality, but we gave them a chuckle. We're allowed to frost their hair, give them highlights, and redo their homes. It was a window into comedic acceptance: Those guys are OK, they get a pass. At the same time, certain fields that are so queer — like anything in the arts or performance — they're trying to build superstars by saying, “Don't be that thing.”

Jim: It was really, really challenging to navigate. They cranked out season after season, so you had this very limited time frame to make something of yourself. You were a fixture on Queer Eye. It was Jai. You just knew who you were every season. It was expected. It was what you would come to know and love. But with Idol, when they went into seasons 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, I moved out to L.A. I didn't have representation, couldn't find an agent. Thank God, I had an email come through from a producer that said, “Hey, I know you took a beating on that show, but we're gonna make a record, and I'm gonna do it with you.” Allan Brocka then reached out to me for [the film] Eating Out. It was tough to make that work in a world of very limited resources. But for you, Queer Eye just exploded.

Jai: I really thought that I was going to become a recording artist and be one of the first out gay recording artists of my age group during that time. When Queer Eye ends, I get this opportunity from Simon Cowell's camp saying, “We're doing this reality show. It is a competition like Idol, with celebrities.” Each week, the celebrities partner with a new music global superstar. I'm killing it. I sing with Patti LaBelle, Taylor Dayne, Michelle Williams of Destiny’s Child, Gladys Knight, and Brian McKnight. I’m the front-runner for a while, and I then think, I’m going to try to release music, do the whole thing. Even with the positioning of a network and a global hit show aligning me and setting me up to be famous, I couldn’t get one door to open.

As someone who was pursuing solely music, when you finally get someone on your side saying, “I want to work with you,” what happened next?

Jim: Gabe Lopez, who has gone on to do great things, reaches out, and he's like, “Let's do this.” And I was like, “I don't know who I want to be. I’m not sure. I think I want to be like a John Mayer.” And he's like, “No, you don’t.” We work and we work and we work and we’re putting music together, and I want to write because I feel like I've got something to prove. If I don’t write, I don't have artistry. Then it's like, Well, it needs to be a hit, and I need to make sure that I'm not using limited pronouns and not just talking to boys. Because I want to make sure that girls like my music too. Yes, I'm gay, we all know this, but I still wanted the opportunity to get as many people to listen as I possibly could. We finish this album, it’s done, and then we shop it. We’re taking it to labels and all they have to do is distribute it. That's all they have to do. Koch Records, this very small indie label in New York City, was like, "We’ll take it, here's a little bit of money, and we’ll get it into stores." They had no money for a stylist in New York to shoot the album artwork. I’m taking crap out of my closet, whatever. I didn’t care, because I had a deal. The PR team did a decent job getting me some radio interviews, but there wasn't crossover. They didn't have that kind of money or that kind of power to make it happen. It was a lot of, "Go to this gay appearance and then go do a Pride event." It was a very boxed-in, not very creative way to get me exposed to a different audience. They just knew what they knew, and that was it. We didn't have a lot of gay representation, particularly in music.

Jai: Lil Nas X and Chappell Roan, they didn't exist. Ricky Martin was still in the closet. Adam Lambert hadn’t quite yet hit the scene. The funny thing is, if you look at Adam Lambert’s audience, it’s still screaming girls. Panties are being thrown. I have a Patreon, and my key demographic is middle-aged women.

Jim: Why is that?

Jai: I post thirst traps. I will say that there is something about a gay man that women feel safe and attracted to. Trying to hide it so much back then followed what we’ve now come to learn was a limited scope — because you might have doubled your audience, the straight girls. How many straight guys are buying tickets? When I think of a concert, I think screaming girls.

Jim: They're always going to be the one that will get their parents to give them the money to go see a concert. They'll do that. I tried it, and I just didn't have the support. I didn't have the representation. I went through a couple of managers who did their best, but had my career just started 10 years later, I just think that opportunities would have been different.

Jai: I think that all the time. All the time. Did you find that like, when you would have these peaks of moments where you're like, “OK, great. I'm in this movie. I'm on the soundtrack. What are we doing next, guys?” Or did you have to create that for the next chapter?

Jim: I remember being taken to this pool party in L.A. and there were a lot of gay execs.

Jai: What kind of pool party?

Jim: No, no, not that kind. She’s no longer with us, but I remember her specifically. She was one of the producers of Eating Out, and this was Eating Out 2. This is the sequel, and I had a much larger role. I was definitely the focus. And I felt, OK, great, this is where things are going to start to move. She was like, “I need you to be the boy next door. You’re going to do please and thank you. Don’t talk too much. Just shake hands and just be effervescent and charming. Don’t be razor-sharp, witty, bitchy — because that’s who you are. And I don’t want to see that today.” And I was just like, Huh, OK, so I am not enough. I am going to take those pieces of me, I’m going to throw them in a lock, and that's gonna be that. I learned how to be a chameleon for whatever room I was in. You always have to be five steps ahead. You always have to network. You have to play the part. You have to be the person they want you to be to a fault if you want to succeed.

I didn’t live in L.A. at the time. I flew in to shoot Eating Out 2. I thought it was going to be enough to get me to the next thing. And then Another Gay Sequel came, and I did a cameo in that. I tried my absolute best during those first three years I lived there, and it was also hard to find a group of people that I think I felt close to. I think if you’re in entertainment in Los Angeles, it's going to be tricky — because you've got to have a good foundation if you're pursuing that. You've got to have friends who are family to get you through the things that are really challenging.

Jai: When it comes to you and this new record, what was the now moment? I think once we went through the pandemic, there was a fire lit within me. Suddenly I was booking more. I knew what I had to do. With you and this album, why now? And why is it that these songs are the ones that came to you?

Jim: I don't think you ever plan to come back. But if you are an artist, if you are an athlete, anything that you have a talent for and you sort of are drawn to it from childhood but then you sort of lose touch with it, it’s like a pilot light, and it burns constantly. You either decide to touch it or you just let it burn. And I just got to a point where, you know, I've been married twice. I've gone through a divorce. I’m 42 years old. I’m a grown-ass man. I'm not coming from the Disney Channel that's trying to hide behind safe material. I want to sing about sex. I want to sing about relationships. I just look at my life now, and I look at how far I've come in just this journey to survive. I see these people in entertainment, in television, in music, and they're all queer, and they're all having insane amounts of success. And I just thought to myself, Maybe I'm not done yet. Maybe I get into the studio and take it a single at a time.

In 2023, I did “Take My Bow.” I threw that out. In the U.K., hit top 5. I was on the same chart as Kylie Minogue, Crystal Waters , Calvin Harris. And then I did another single in 2024 — it hit top 6. And I'm like, OK, let's put an EP together.

Jai: I'm glad that when those moments happen, that it signaled something in you to remember we're not done yet — because the the worst thing we can do is equate our value to our current visibility, to our current relevance. These new kids, they come off a show like Drag Race or something. They’re feeling so hot, you know what? Boo, come to me in 27 years and let me know if you're still doing big things in the industry, if you've had a cultural impact on society. The reason why some of these things have been so difficult for us is because we became the first to do a lot of stuff. So many of us that were carving this trail, it’s harder for us, easier for them, and they are making it easier for the people that come behind them.

Charlie Kirk DID say stoning gay people was the 'perfect law' — and these other heinous quotes

These are some of his worst comments about LGBTQ+ people made by Charlie Kirk.